The muscles of the torso, examined in the previous chapter, include a few that attach directly into the upper arm and help move the humerus at the shoulder joint. In this chapter we will look at the other arm muscles as well as the muscles of the hands, seeing how they move the lower arm at the elbow joint, the hand at the wrist joint, and the fingers and thumb at the interphalangeal (IP) joints.

Some figures’ arms are fairly easy to depict, but others’ arms are more challenging. “Average” arms, which are basically cylindrical, streamlined structures, are relatively simple. In these arms, most muscles are inconspicuous because they are covered by a subcutaneous layer of fatty tissue, softening the surface form. A few muscles—the deltoid, biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis—may, however, exhibit interesting shapes even on nonmuscular arms, altering shape in various arm movements.

By contrast, the arms of a person with an athletic build have many well-defined muscular bulges and ridges. One potential difficulty in depicting a muscular arm has to do with the spiraling of muscle forms that occurs when the lower arm twists, which may cause confusion about what you are seeing on the surface form.

There are, however, ways to identify the basic muscles within specific arm regions using bony landmarks as guides. And learning the locations of the muscles of the upper and lower arm in a systematic way, as well as their roles in movement, will improve the accuracy of your depictions.

To comprehend the vast complexity of the arm region, anatomists organize arm muscles into groups. There are several ways to do this. Some texts categorize arm muscles according to which body parts they move: muscles that move the forearm, muscles that move the wrist, and so on. A variation of this is to group the muscles according to the roles they generally play in movement: flexors, extensors, pronators, supinators, abductors, and adductors.

Arm muscles can also be classified by their compartments or regions. Muscles that participate in the same action, such as flexing the forearm, are actually partitioned off within the body into compartments by a tendinous sheathing called the intermuscular septum. Each of these various compartments is related to a certain region of the arm—anterior, posterior, medial, or lateral—which helps clarify its general location.

Yet another way to categorize arm muscles is to group them according to their relationship to the surface. The muscles closest to the surface belong to the superficial muscle layer. If a region has more than one muscle layer, muscles farther from the surface may be identified as belonging to the intermediate muscle layer or the deep muscle layer.

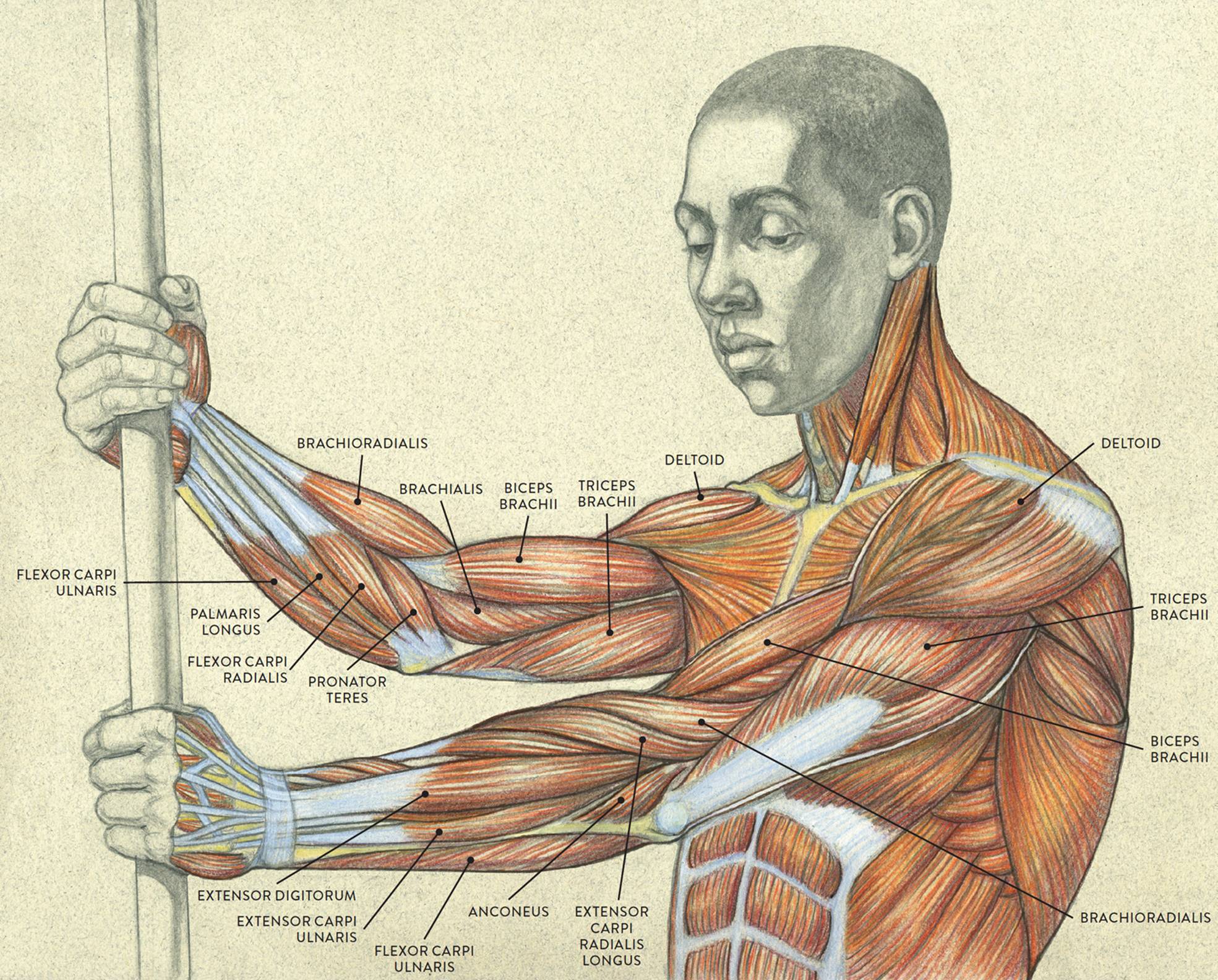

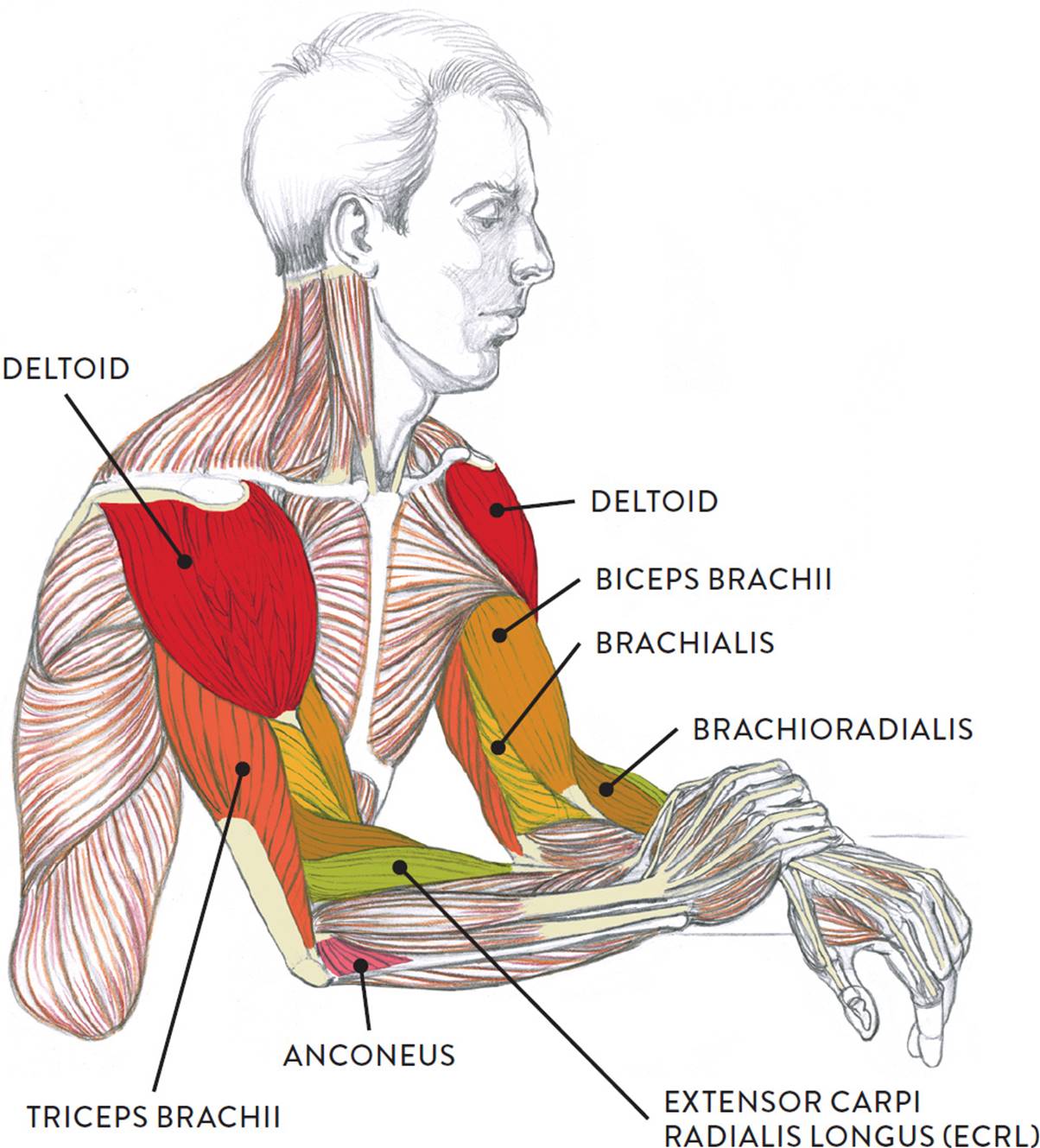

In this chapter, I use a combination of such systems, identifying muscle groups by the regions they occupy, the actions they perform, and the layers in which they are positioned. The drawings here provide a visual overview of the muscles and muscle groups of the entire arm as seen from various views. (Note that the deltoid muscle was covered at the end of the previous chapter.)

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER AND LOWER ARM

Left arm

LEFT: Anterior three-quarter view

CENTER: Lateral view

RIGHT: Posterior three quarter view

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER AND LOWER ARM

Upper torso, three-quarter view

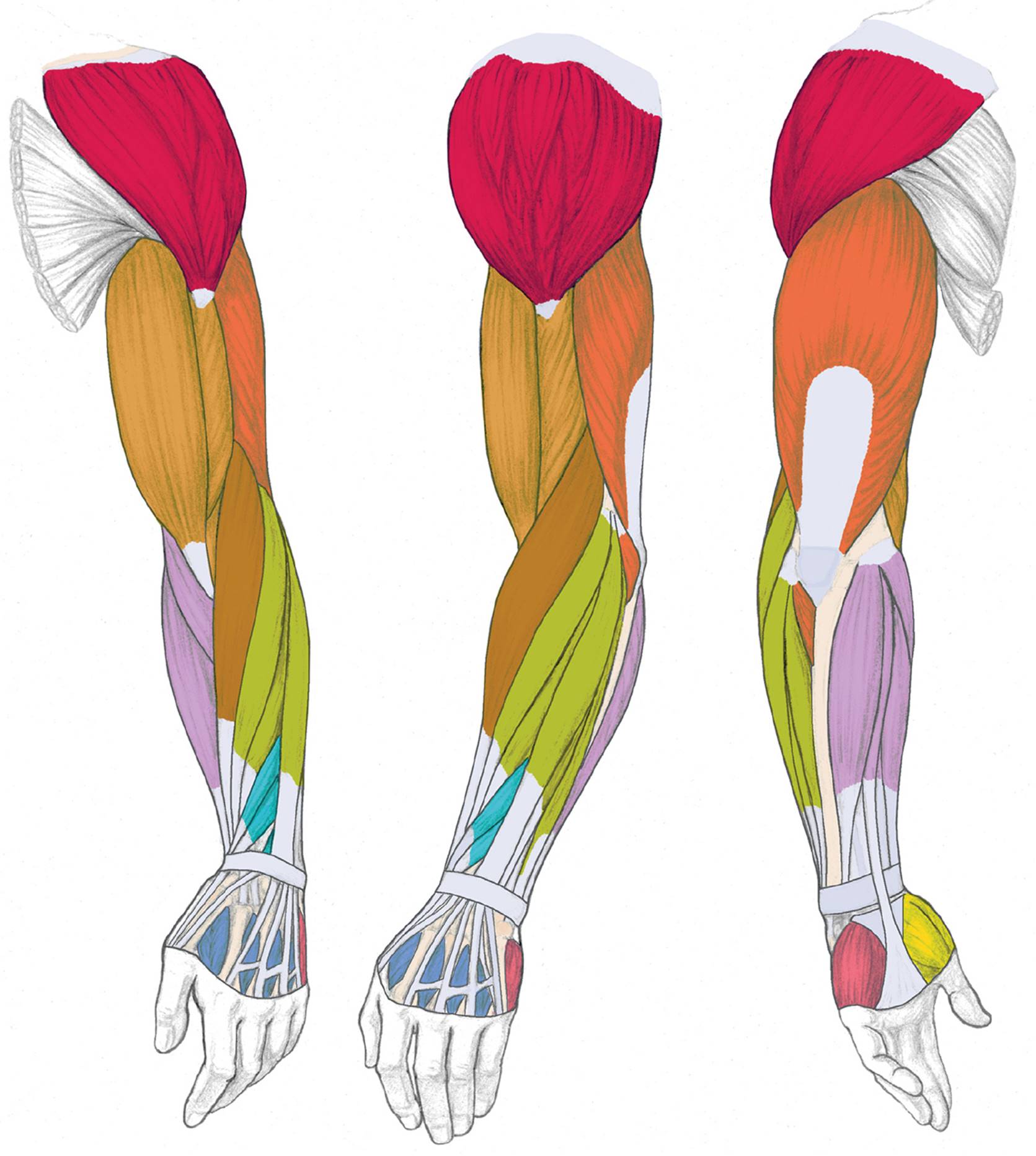

MUSCLE GROUPS OF THE UPPER AND LOWER ARM, INCLUDING HAND

Left arm

LEFT: Anterior three-quarter view

CENTER: Lateral view

RIGHT: Posterior three quarter view

MUSCLES AND MUSCLE GROUPS OF THE UPPER AND LOWER ARM

DELTOID MUSCLE

FLEXOR MUSCLE GROUP OF UPPER ARM

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF UPPER ARM

BRACHIORADIALIS (PART OF RADIAL MUSCLE GROUP)

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF LOWER ARM (SUPERFICIAL LAYER)

FLEXOR MUSCLE GROUP OF LOWER ARM

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF LOWER ARM (DEEP LAYER), ANATOMICAL SNUFFBOX MUSCLES

MUSCLE GROUPS OF THE HAND

THENAR MUSCLE GROUP

HYPOTHENAR MUSCLE GROUP

DORSAL INTEROSSEOUS MUSCLE GROUP

Muscle Groups of the Upper Arm

We begin our closer examination with the muscles of the upper arm by dividing them into two basic groups: the flexor muscle group, located on the anterior region of the upper arm, and the extensor muscle group, located on the posterior region.

Names of Arm and Hand Muscles

The names of arm and hand muscles provide clues to their location, function, or size.

· Brachialis, brachio, and brachii pertain to the upper arm.

· Carpi pertains to the carpal bones of the wrist.

· Coraco pertains to the coracoid process of the scapula.

· Digitorum and digiti pertain to the fingers (digits).

· Dorsal pertains to the back of the hand.

· Interosseous means “between bones.”

· Palmar and palmaris pertain to the palm side of the hand.

· Pollicis pertains to the thumb.

· Radialis pertains to the radius bone of the lower arm.

· Ulnaris pertains to the ulna bone of the lower arm.

· Abductor pertains to moving a body part away from the midline.

· Adductor pertains to moving a body part back toward the midline.

· Extensor pertains to stretching.

· Flexor pertains to bending.

· Brevis means “short.”

· Longus means “long.”

· Minimi means “little.”

· Profundus means “deep.”

The Flexor Muscle Group of the Upper Arm

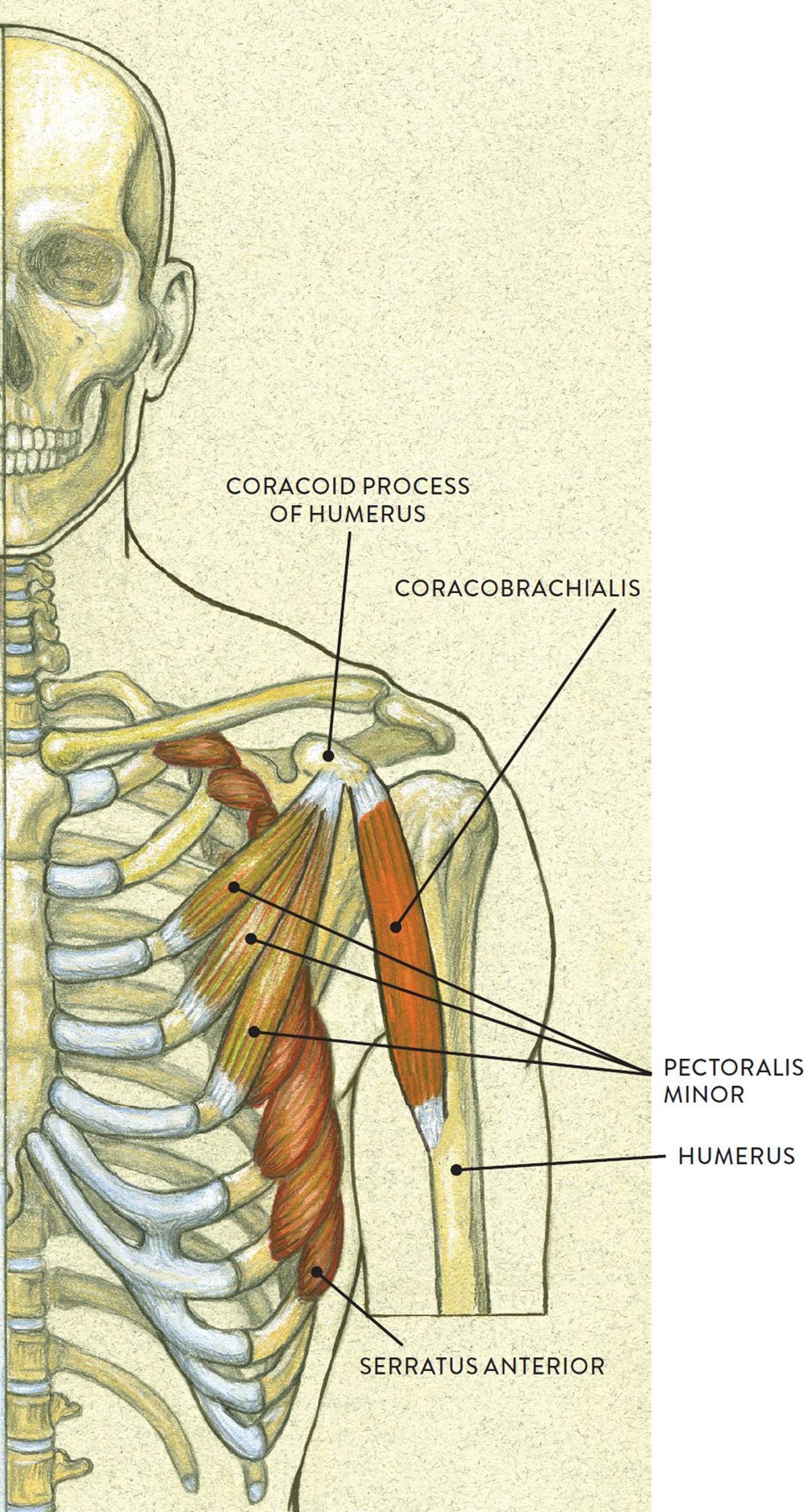

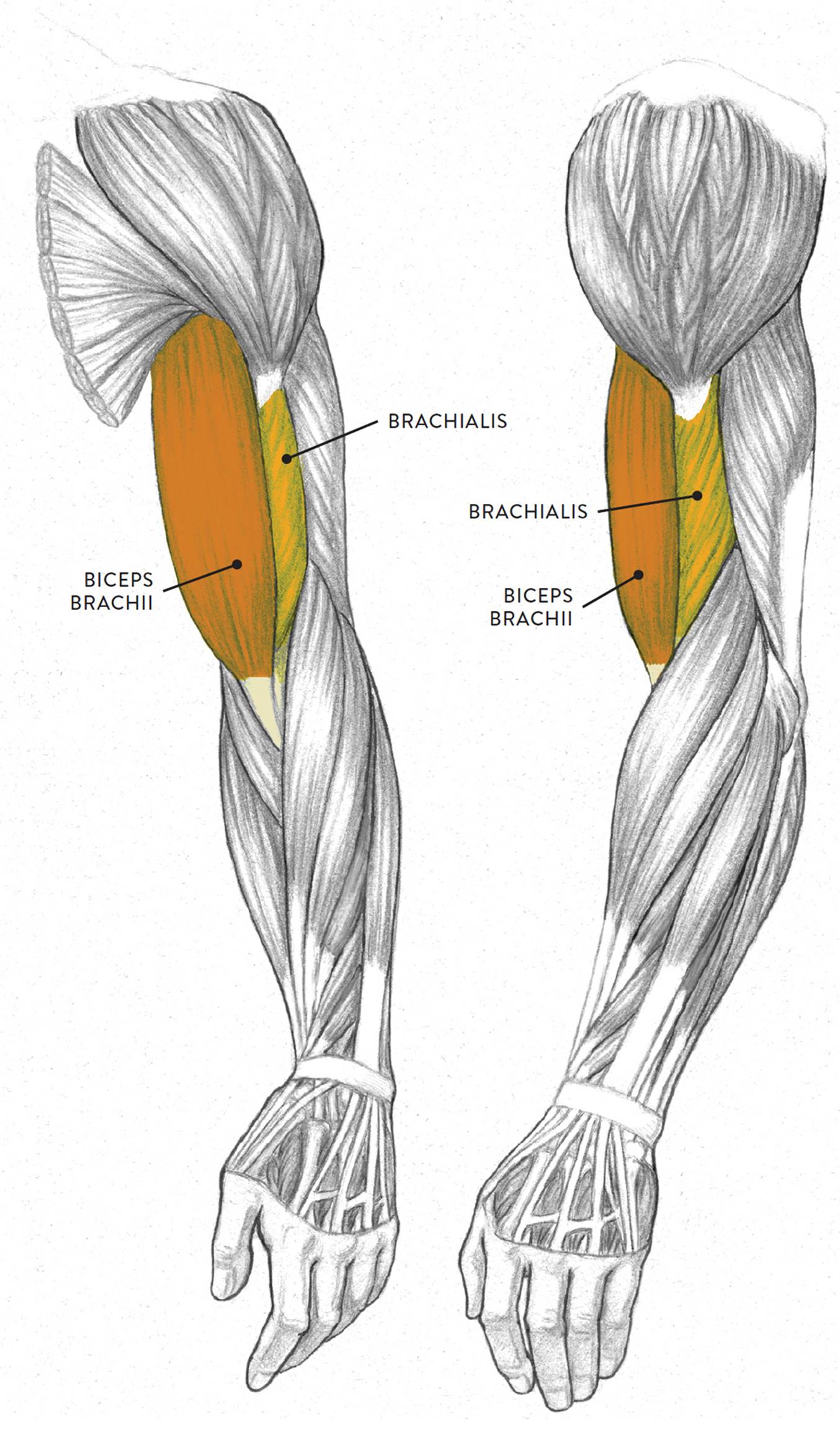

The flexor group of the upper arm is positioned on the anterior region of the humerus. Muscles belonging to this group are the biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis. The biceps brachii is the most prominent, taking up most of the front of the upper arm region. The brachalis is mainly hidden by other muscles, with only a small area seen on the surface. The coracobrachialis, positioned behind the biceps brachii, can only be seen when the arm is lifted overhead. The biceps brachii and brachialis appear in the drawing opposite; the coracobrachialis is shown separately, in the following drawing.

CORACOBRACHIALIS

Skeletal torso, anterior view

The biceps brachii (pron., BI-seps BRAY-kee-ee or BI-seps BRAKE-ee-eye) is a two-headed fusiform muscle located on the front region of the upper arm, or humerus. Elongated when relaxed, the biceps brachii changes shape when its muscle fibers contract, becoming tightly compact. On muscularly defined arms, the biceps looks like a small melon when contracted.

The long head of the muscle begins on the scapula above the glenoid fossa at the supraglenoid tubercle, which is a small projection of bone. The short head begins on the coracoid process of the scapula. At the other end of the biceps brachii is a single tendon, which attaches on the radius bone of the lower arm on a small protrusion called the radial tuberosity. The biceps brachii moves the lower arm toward the upper arm from the elbow joint (flexion) and also rotates the lower arm from the elbow joint (supination).

The brachialis (pron., BRAY-kee-al-iss or bray-kee-AA-liss) is a slightly flattened fusiform muscle mostly covered by the biceps brachii. On an average arm the brachialis is hard to detect, but on a muscularly defined arm the muscle can been seen as a slight bulge between the triceps and the biceps. The brachialis begins on the lower half of the humerus and inserts into the coronoid process of the ulna. The muscle assists the biceps brachii in bending the forearm toward the upper arm from the elbow joint (flexion).

The coracobrachialis (pron., KOR-ah-ko-BRAY-kee-al-iss) is a small elongated fusiform muscle positioned beneath the biceps brachii of the upper arm. The muscle can only be seen on the surface when the upper arm is raised overhead, appearing as small ridgelike form next to the short head of the biceps brachii in the armpit region. The muscle begins on the coracoid process, a small bony projection, shaped like a bird’s beak, on the scapula. It then inserts into the medial side of the humerus. The coracobrachialis helps bend the humerus (flexion), rotates the humerus in an inward direction (medial rotation), and brings the abducted humerus back to its normal location (adduction).

FLEXOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE UPPER ARM

Left upper and lower arm

LEFT: Anterior three-quarter view

RIGHT: Lateral view

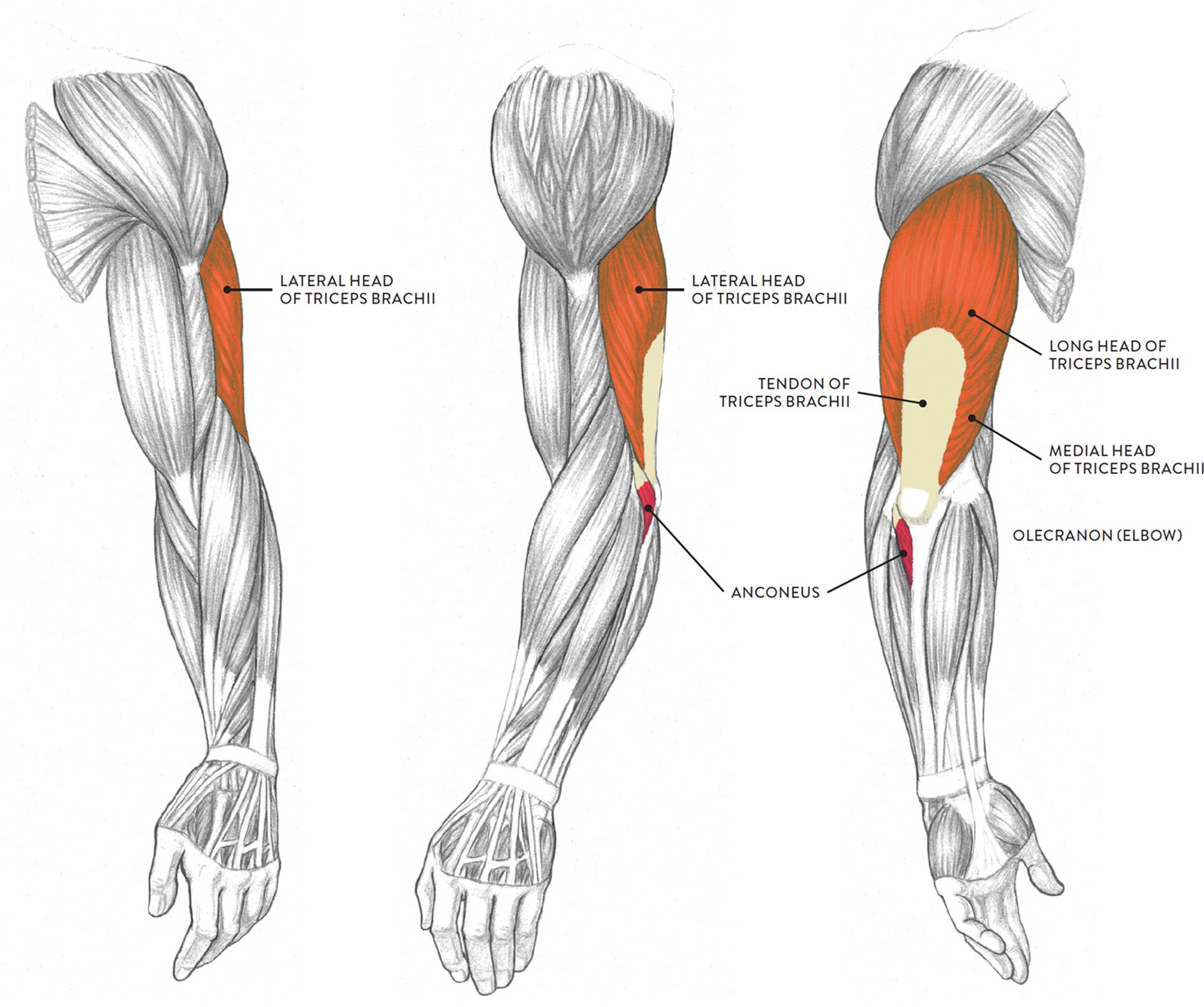

The Extensor Muscle Group of the Upper Arm

The two muscles of the extensor group of the upper arm are the triceps brachii and the anconeus, as shown in the following drawing. The triceps brachii is located on the posterior region of the upper arm, while the anconeus is located on the posterior region of the lower arm, near the elbow. They help straighten the lower arm (ulna) from a flexed or bent position.

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE UPPER ARM

Left upper and lower arm

LEFT: Anterior three-quarter view

CENTER: Lateral view

RIGHT: Posterior three-quarter view

The triceps brachii (pron., TRI-seps BRAY-kee-ee or TRI-seps BRAKE-ee-eye) is a large three-headed muscle occupying most of the posterior aspect of the upper arm. The three heads are the lateral (outer) head, the long head,and the medial (inner) head. If the triceps of the upper arm is significantly developed, a fleshy horseshoe shape will appear on the surface when the muscle contracts—the combined shapes of the heads surrounding the neutral tendon. If the muscle is not well developed, then the back of the relaxed upper arm registers as a cylindrical shape, with very little indication of the triceps heads. On an “average” upper arm, the outer head and long head will appear as two bulges on the surface form only when the muscle is contracting.

The lateral head of the triceps brachii begins on the posterior and lateral surfaces of the humerus. The medial head begins on the posterior and medial surfaces of the humerus. The long head begins on the scapula below the glenoid fossa at a small triangular region called the infraglenoid tubercle. The muscle fibers of all three heads merge into a large flat tendon that inserts into the olecranon process (elbow) of the ulna. The triceps brachii straightens the lower arm at the elbow joint (extension). The long head assists in the action of adduction of the humerus, which is moving an abducted humerus back to the side of the body.

The anconeus (an-KOH-nee-us) is a small triangular muscle located between the olecranon (elbow) of the ulna and the radial muscle group. Its fleshy mass is at times noticeable on the surface, depending on the position of the arm. The muscle begins on the humerus, at the lateral epicondyle, and inserts into the ulna on the upper part of the bone’s posterior surface. Along with the triceps brachii, the anconeus helps straighten the lower arm at the elbow (extension).

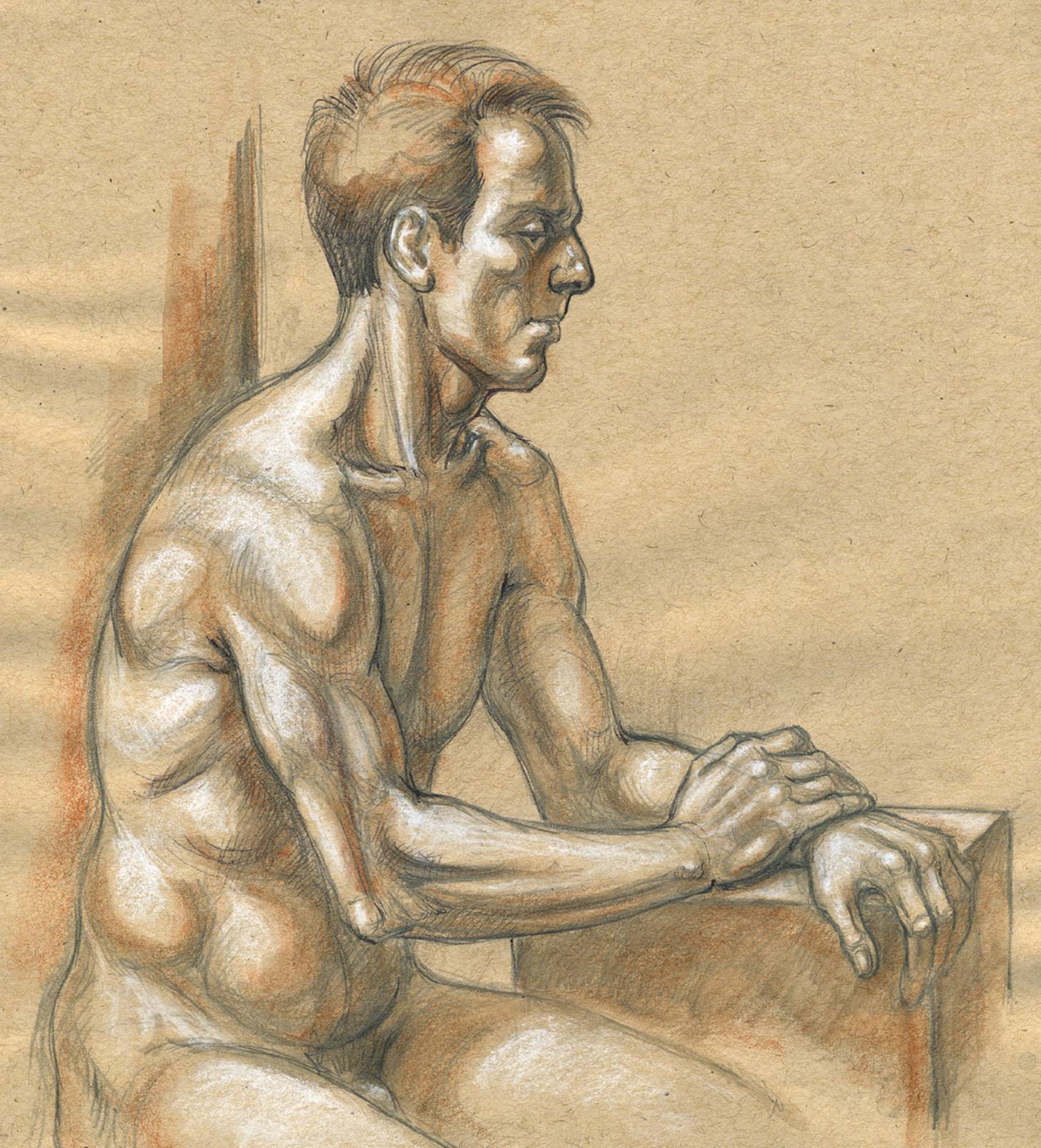

The muscles of the upper arm can be clearly seen in the well-defined arms of the model in the life study Male Figure Resting with One Hand over the Other Arm. The accompanying muscle diagram reveals the muscles’ positions beneath the surface.

MALE FIGURE RESTING WITH ONE HAND OVER THE OTHER ARM

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, watercolor pencil, and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

Muscle Groups of the Lower Arm

Of all the body’s muscles, those of the lower arm may be the most challenging to learn, for several reasons:

1. Some of these muscles have very similar names (e.g., flexor carpi ulnaris and extensor carpi ulnaris), which often causes confusion.

2. The various lower arm muscles look very similar to each other on écorché charts, appearing as slender muscles with extremely long tendons. (Écorché charts are diagrams showing the figure without skin or subcutaneous tissue, so that the muscles are clearly visible.)

3. On the surface, the muscles of the lower arm generally register as a single form rather than as distinct, obvious shapes like the biceps brachii or deltoid, making them difficult to locate.

4. When the lower arm rotates at the elbow joint, these muscles engage in a spiraling action, further contributing to the complexity of this region.

It is possible, however, to locate the muscles’ general whereabouts as the lower arm moves to different positions. One key is to keep an eye on the bony landmarks of the arms, such as the medial and lateral condyles of the humerus, which are important attachment sites for various lower arm muscles. Muscles also attach along the ulna, which can be located by tracing a line from the elbow (olecranon) down the little-finger side of the hand to the ulna head, the small protrusion of bone at the outer wrist. (The radius bone, located on the thumb side of the hand, is harder to detect on the surface.)

The lower arm has three muscle layers on the anterior region: the superficial layer, the intermediate layer, and the deep layer. On the posterior region, there are just two: the superficial layer and the deep layer. Although the discussion that follows focuses mostly on the superficial layer, the intermediate and deep layers are introduced to give you an idea of how the forms are built atop one another.

Like the muscles of the upper arm, some of the muscles of the lower arm are divided into flexor and extensor muscle groups located in the three layers (superficial, intermediate, and deep). Knowing the meanings of these terms can help you locate certain muscles and give you a better sense of their roles in movement. A muscle with the term flexor in its name is probably located on the anterior region of the lower arm, and its primary action is to flex, or bend, the hand and fingers (depending on the layer). A muscle with the term extensor in its name is probably located on the posterior region of the lower arm, and its primary action is to extend, or straighten, the hand, fingers, and thumb (again depending on the layer). In addition to the flexor and extensor muscle groups, the muscles of the lower arm include the radial muscle group, which is located in the lateral (outer) region of the lower arm. As its name implies, this group is positioned along the radius bone of the lower arm. Note that some lower arm muscles (e.g., the extensor carpi radialis longus) may be classified as belonging to more than one group.

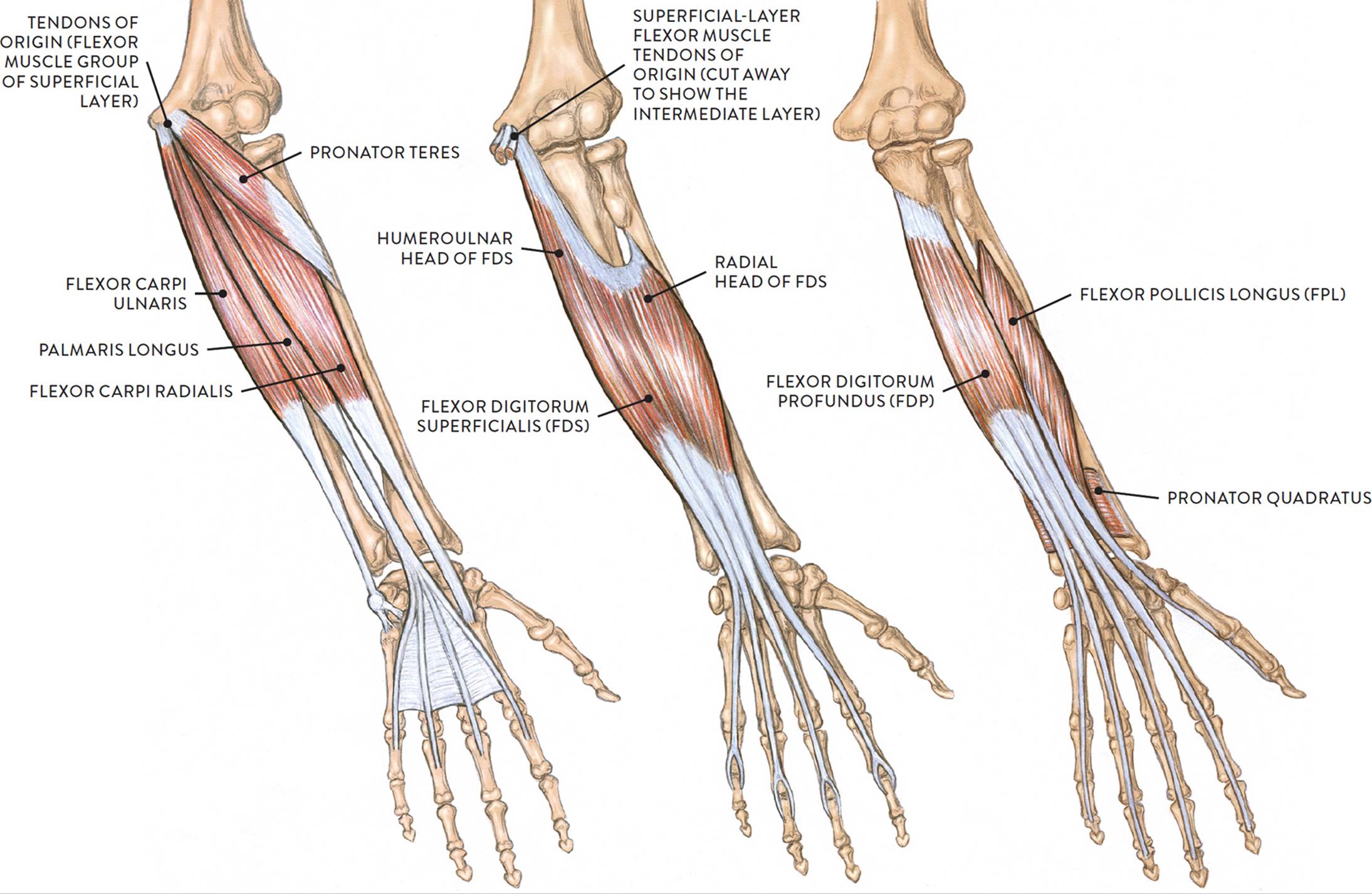

The Flexor Muscle Group of the Lower Arm

Let’s look first at the flexor muscle group of the anterior region of the lower arm. There are three muscle layers in this region: superficial, intermediate, and deep. The following drawing shows the three layers from the anterior view. In all three views, the lower left arm is positioned with the palm facing toward the viewer.

FLEXOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER ARM

Lower left arm, anterior view, palm facing front

LEFT: Superficial layer

CENTER: Intermediate layer

RIGHT: Deep layer

Anterior Region, Superficial Muscle Layer (of the Flexor Muscle Group)

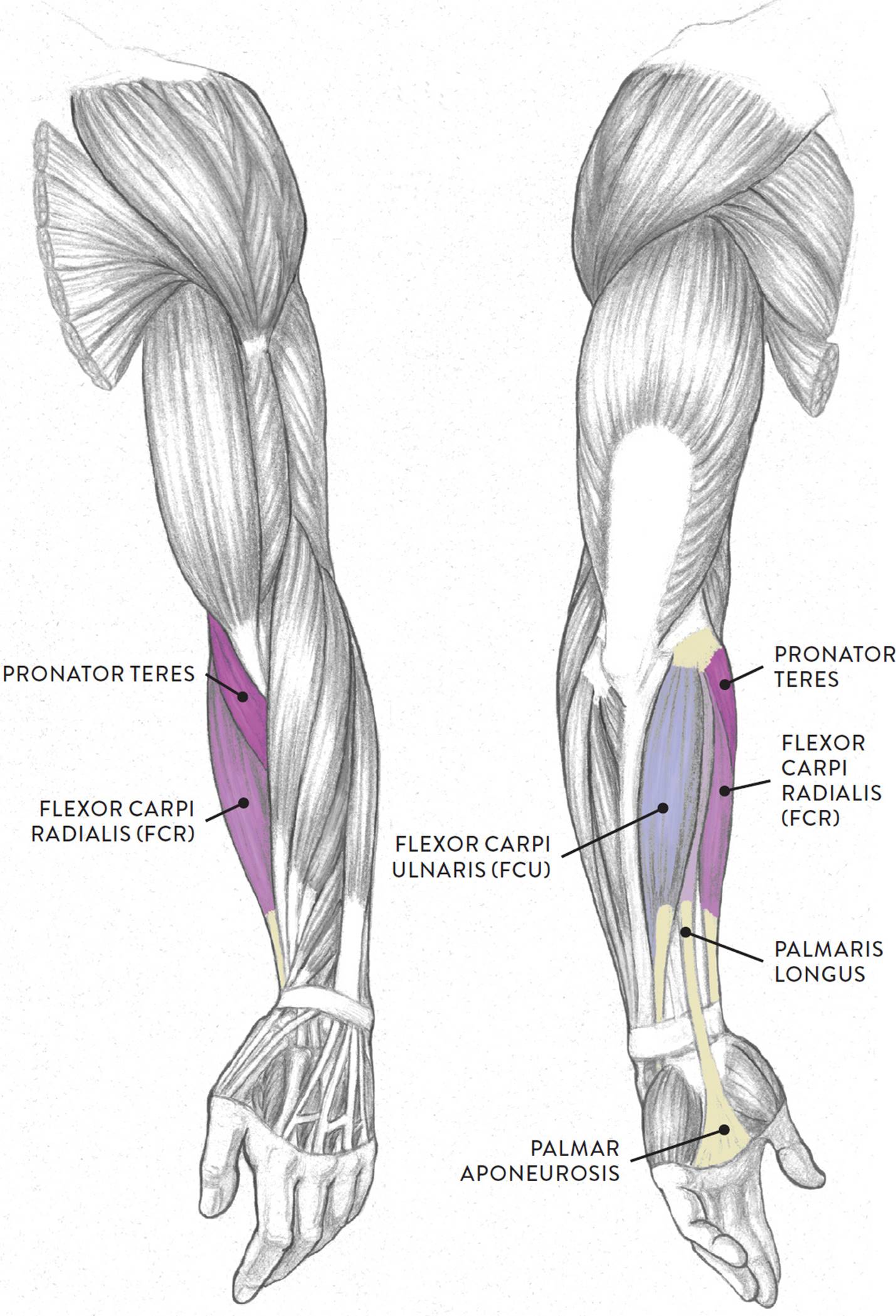

Four main muscles of the anterior region of the lower arm begin on the medial epicondyle of the humerus. These are the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, and flexor carpi ulnaris. With the exception of the pronator teres, these muscles insert into the general anterior region of the hand and are responsible for moving the hand at the wrist joint.

The pronator teres (pron., pro-NAY-tor TEH-reez or PRO-nay-tor TEH-reez) has two heads: a humeral head, which begins on the medial epicondyle of the humerus, and an ulnar head, which begins on the corocoid process of the ulna bone. Both heads merge and insert about midway along the shaft of the radius bone. The pronator teres muscle assists in rotating the lower arm (pronation) and helps bend the lower arm at the elbow joint (flexion).

The flexor carpi radialis (pron., FLEK-sor KAR-pea ray-dee-AL-iss or FLEK-sor KARP-eye RAY-dee-ah-liss), or FCR, is a slender muscle positioned on the thumb side of the lower arm. The muscle begins on the medial epicondyle of the humerus and the antebrachial fascia, which is the deep fascia of the lower arm. It inserts by way of a long slender tendon into the bases of the second and third metacarpal bones of the hand. The flexor carpi radialis bends the hand toward the inner lower arm (flexion of the hand at the wrist joint) and assists in bending the hand sideways at the wrist (radial abduction of the hand at the wrist joint).

The palmaris longus (pron., pahl-MAR-iss LON-gus) is a thin muscle positioned in the middle of the lower arm. The muscle begins on the medial epicondyle of the humerus. Halfway down the shaft of the lower arm it becomes a slender tendon that, when it passes the wrist, flares out into a fan shape and inserts into the palmar aponeurosis, a fibrous sheathing of the palm. The palmaris longus helps bend the hand toward the inner lower arm (flexion of hand at wrist joint). It also helps tense or tighten the palmar aponeroneus and skin during certain hand movements, such as gripping an object.

The flexor carpi ulnaris (pron., FLEK-sor KAR-pea ull-NARE-iss or FLEK-sor KARP-eye ull-NARE-iss), or FCU, is positioned on the outer edge of the ulna bone for nearly its entire length. It has two heads: a humeral head and an ulnar head. The humeral head begins on the medial epicondyle of the humerus, and the ulnar portion begins near the olecranon (elbow) and the upper two-thirds of the posterior border of the ulna. The muscle inserts into the pisaform and hamate carpal bones, the fifth metacarpal bone, and the flexor retinaculum, which is a bracelet-like fibrous sheathing of the wrist region. The flexor carpi ulnaris bends the hand toward the inner lower arm (flexion of the hand at the wrist joint) and assists in bending the hand sideways (ulnar adduction at the wrist joint).

FLEXOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER ARM, SUPERFICIAL LAYER

Left upper and lower arm

LEFT: Anterior three-quarter view

RIGHT: Posterior three-quarter view

Anterior Region, Intermediate Muscle Layer (of the Flexor Muscle Group)

The flexor digitorum superficialis (pron., FLEK-sor dij-ih-TOR-um SOO-pur-FISH-ee-AL-iss), or FDS, is positioned beneath the superficial-layer flexor muscles discussed just above. Some experts consider it part of the superficial muscle layer, hence its name. Others, however, classify it as belonging to an intermediate muscle layer between the superficial and deep layers of the lower arm.

The flexor digitorum superficialis has two heads: the humeroulnar head and the radial head. The humeroulnar head begins on the medial epicondyle of the humerus and the coronoid process of the ulna. The radial head begins on the radius. The muscle splits into four tendons, each of which inserts into the middle phalange of each finger. The flexor digitorum superficialis bends the fingers at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints (flexion of fingers). It also helps bend the hand (flexion of the hand at the wrist joint).

Anterior Region, Deep Muscle Layer (of the Flexor Muscle Group)

The three flexor muscles of the deep muscle layer are situated beneath the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle. These muscles—the flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, and pronator quadratus—move the fingers and thumb and help move the hand and lower arm (radius) at the wrist joint.

The flexor digitorum profundus (pron., FLEK-sor dij-ih-TOR-um pro-FUN-dus), or FDP, influences the surface form by creating a muscular mass of the inner forearm, along with the flexor carpi ulnaris. The muscle begins on the ulna and interosseous membrane (the connective tissue between the two bones of the lower arm) and then splits into four separate tendons, each inserting into a finger. The flexor digitorum profundus bends the fingers (flexion of fingers) at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints and helps bend the hand (flexion of hand at the wrist joint).

The flexor pollicis longus (pron., FLEK-sor pawl-lih-kiss LON-gus or FLEK-sor poe-LEE-siss LON-gus), or FPL, while being a deep-layer muscle, also contributes to the surface form on the anterior region of the lower arm, on the radial side. The muscle attaches on the radius and interosseous membrane and inserts into the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb. The flexor pollicis longus bends the thumb (flexion of the thumb) at the MCP and IP joints.

The pronator quadratus (pro-NAY-tor kwa-DRAH-tus) is a quadrangular muscle located on the lower portions of the radius and ulna bones. The muscle is so deep that some texts categorize it as belonging to a fourth muscle layer of the lower arm. The pronator quadratus begins on the ulna (medial and anterior surfaces) and inserts into the radius (anterior lateral surface). As its name implies, it helps rotate the lower arm and hand in the action of pronation.

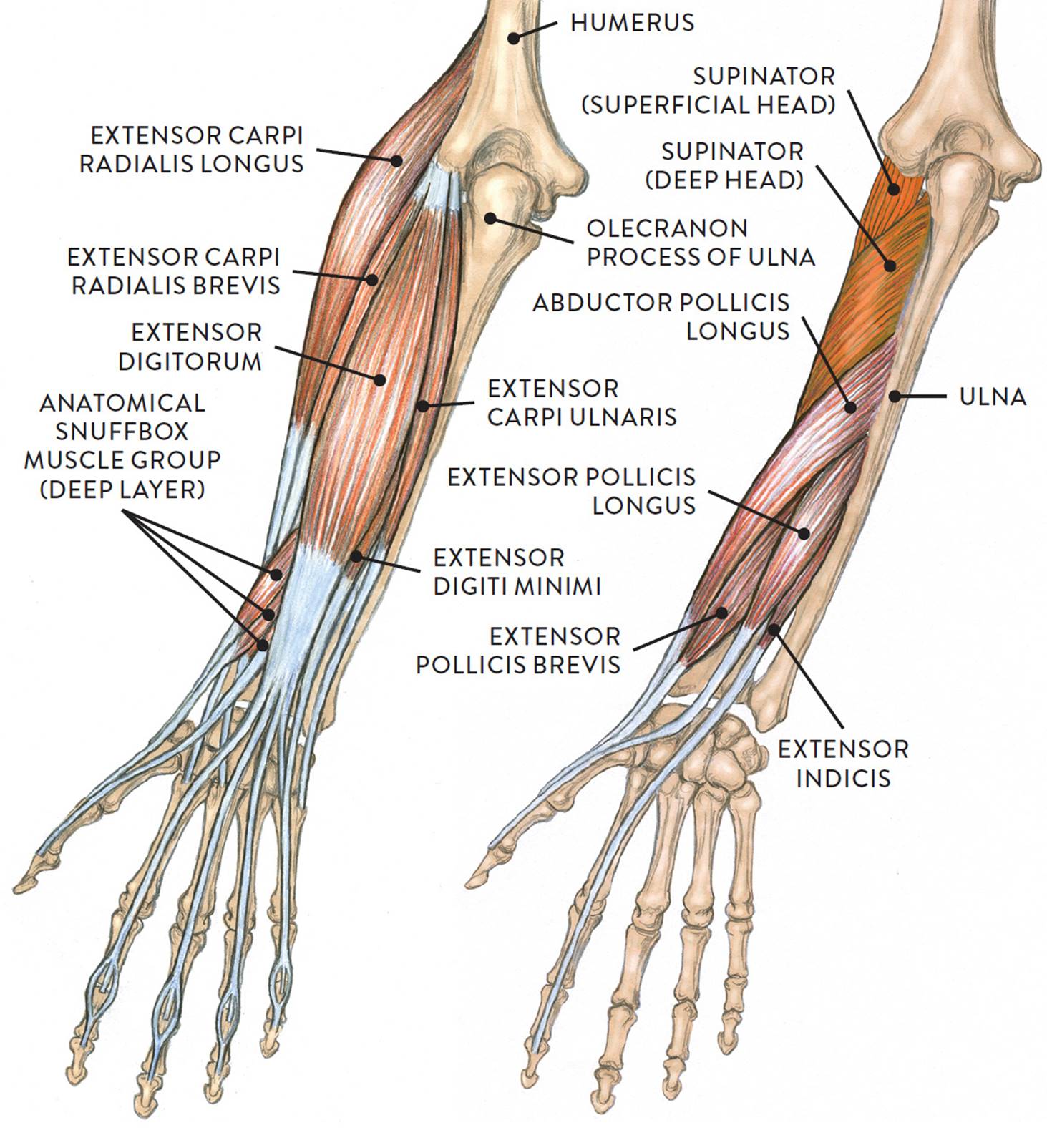

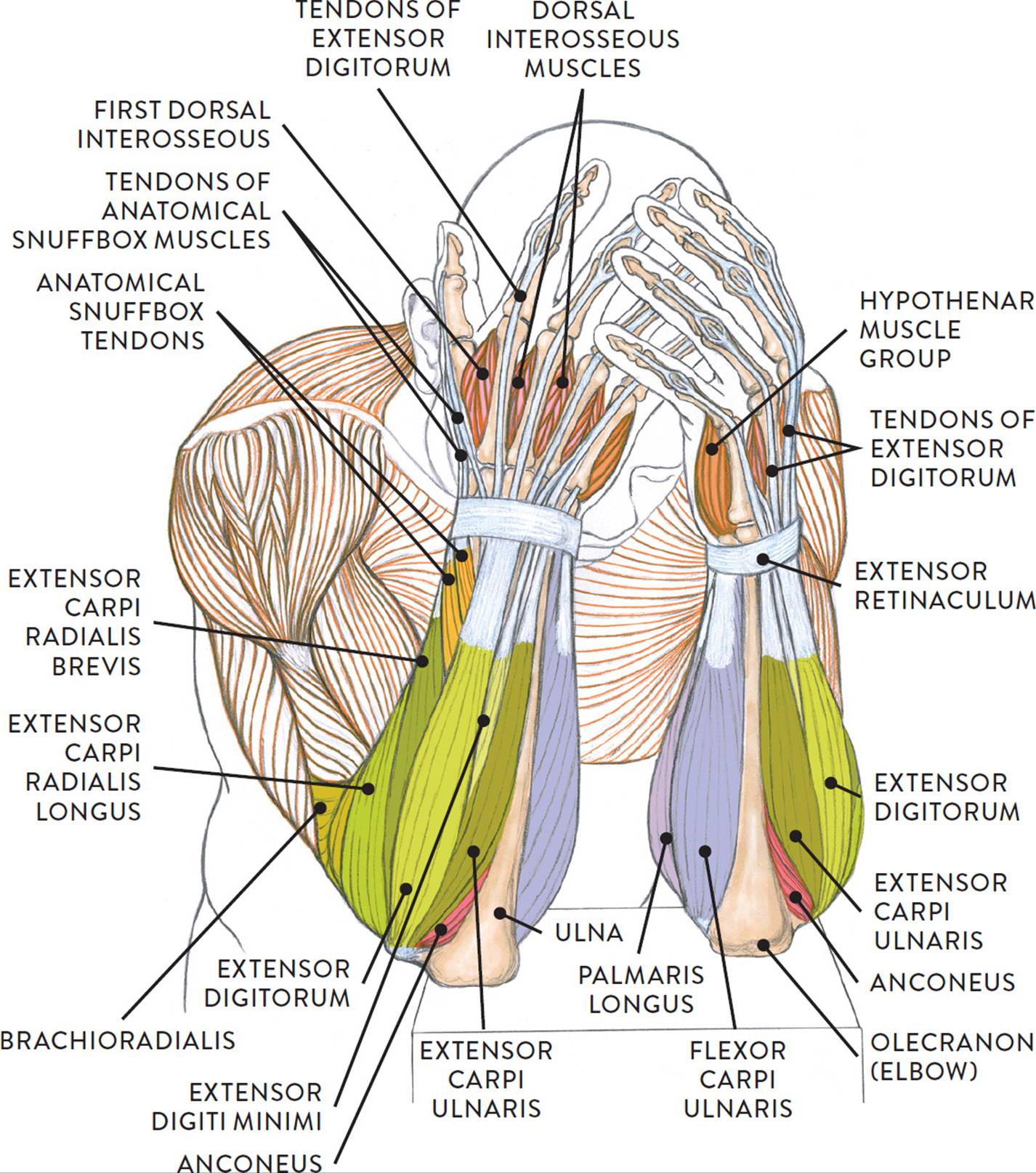

The Extensor Muscle Group of the Lower Arm

Now we move on to the extensor muscle group of the posterior side of the lower arm, which has two muscle layers: superficial and deep. The muscles of these layers are shown in the following drawing. In both views, the lower left arm is positioned with the back (dorsal side) of the hand facing toward the viewer.

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER ARM

Lower left arm, posterior view, back of hand facing front

Posterior Region, Superficial Muscle Layer (of the Extensor Muscle Group)

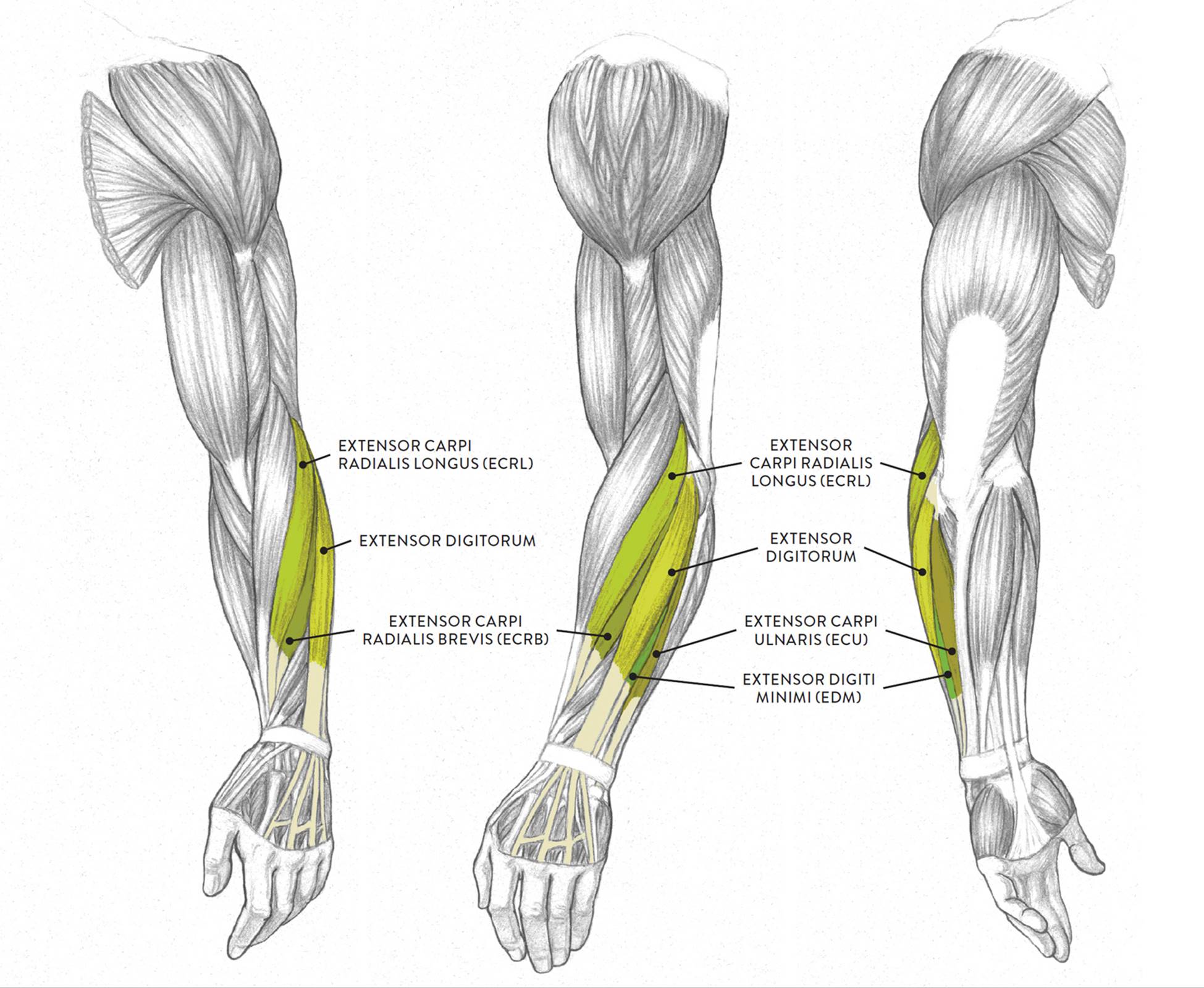

The extensor muscle group of the superficial layer of the lower arm includes the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL), the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), the extensor digitorum, the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU), and a small muscle called the extensor digiti minimi (EDM), all shown in the next drawing. All these muscles except the ECRL begin on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, sharing a common tendon at this location. The ECRL begins above the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and does not share the common tendon of origin. The individual muscles insert by way of elongated tendons into various bones of the hand on the dorsal side. All four extensor muscles help move the hand at the wrist joint, and the extensor digitorum moves the fingers at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, and the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints.

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER ARM, SUPERFICIAL LAYER

Left upper and lower arm

LEFT: Anterior three-quarter view

CENTER: Lateral view

RIGHT: Posterior three-quarter view

The extensor carpi radialis longus (pron., ek-STEN-sor KAR-pea ray-dee-AA-lis LON-gus or ek-STEN-sor KARP-eye RAY-dee-ah-liss LON-gus), or ECRL, is an elongated fusiform muscle that travels parallel to the brachioradialis. This muscle, which is also part of the radial muscle group of the lower arm, begins on the lower part of the humerus, above the lateral epicondyle and slightly below where the brachioradialis begins. It eventually inserts by way of a long, slender tendon on the second metacarpal bone of the hand. The ECRL helps straighten the hand at the wrist joint (extension) and also moves the hand in a side direction on the radial side of the lower arm (radial abduction).

The extensor carpi radialis brevis (pron., ek-STEN-sor KAR-pea ray-dee-AA-liss BREH-viss or ek-STEN-sor KARP-eye RAY-dee-ah-liss BREV-iss), or ECRB, is a slender muscle positioned between the ECRL and the extensor digitorum muscle on the posterior side of the lower arm. It begins on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and inserts into the third metacarpal bone of the hand. The ECRB assists in straightening the hand at the wrist joint (extension) and in moving the hand in a sideways direction at the wrist (radial abduction).

The extensor digitorum (pron., ek-STEN-sor dij-ih-TOR-um) is positioned on the posterior side of the lower arm between the ECRB and the extensor carpi ulnaris. The muscle begins on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. About halfway down its length, the muscle merges into a flat broad tendon, which then splits into four slender tendons at the wrist, which insert into the fingers via the four tendons. The extensor digitorum helps straightens the hand at the wrist joint and straightens the four fingers at the MCP joints (extension), PIP joints, and DIP joints.

The extensor digiti minimi (pron., ek-STEN-sor DIH-jih-tee MIN-ih-mee or ek-STEN-sor DIJ-ih-tie MIN-ih-my), or EDM, is an extremely slender fusiform muscle with an elongated tendon. It is linked to the extensor digitorum muscle. It begins on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and inserts (along with the tendon of the extensor digitorum) into the fifth finger (little finger). The EDM straightens the fifth finger at the PIP and DIP joints.

The extensor carpi ulnaris (pron., ek-STEN-sor KAR-pea ull-NARE-riss or ek-STEN-sor KARP-eye ull-NARE-riss), or ECU, is a two-headed fusiform muscle with a long tendon that is positioned on the medial/posterior region of the lower arm. The humeral head begins on the lateral epicondyle, and the ulnar head begins on the posterior border of the ulna and inserts into the fifth metacarpal bone of the hand. The ECU straightens the hand at the wrist (extension) and moves the hand in a sideways direction at the wrist (ulnar adduction).

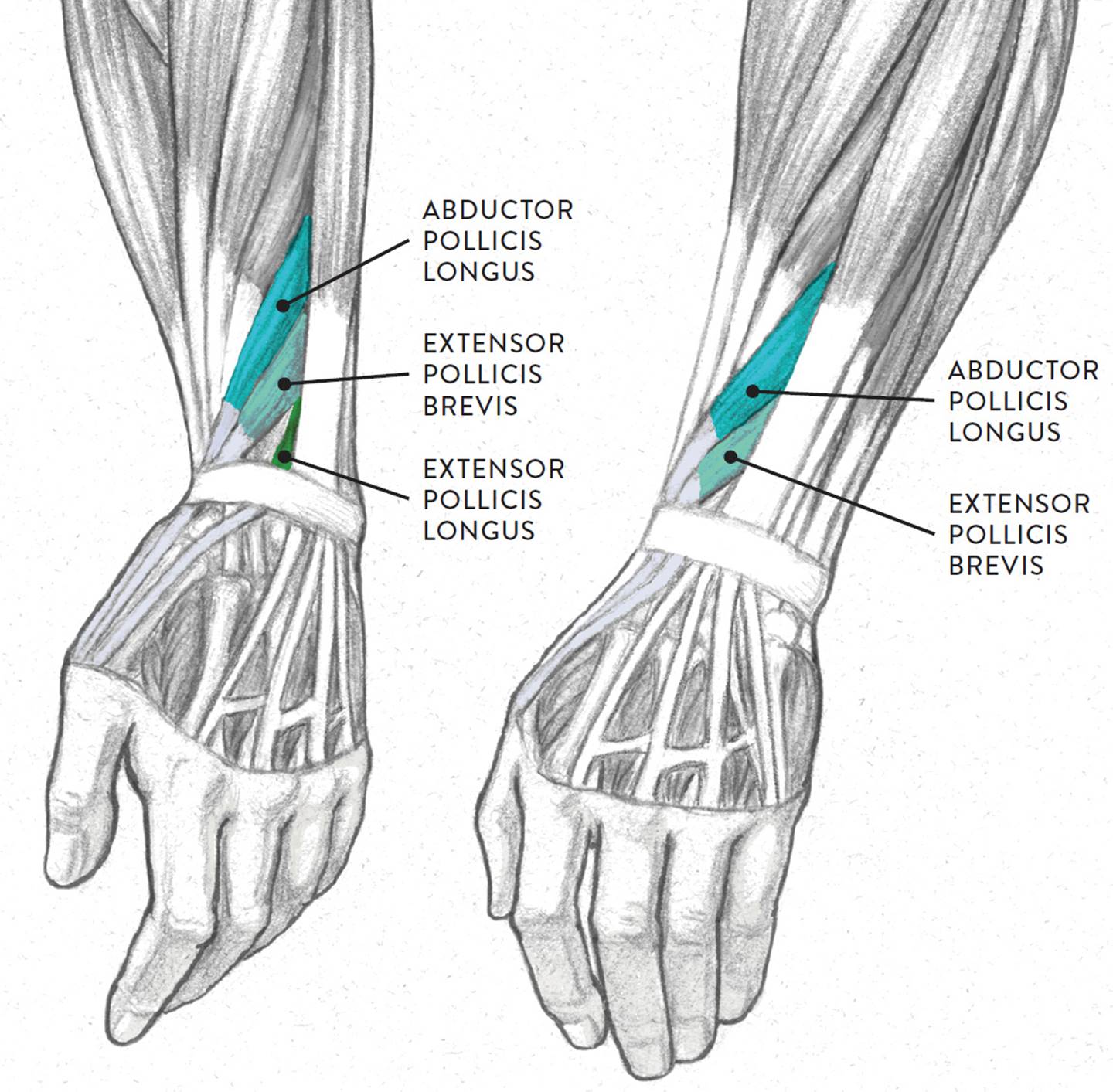

Posterior Region, Deep Muscle Layer (of the Extensor Muscle Group)

Located in the deep muscle layer of the posterior region of the lower arm is a group of muscles colloquially called the anatomical snuffbox muscles because their long tendons create an elongated triangular depression, called the anatomical snuffbox, in the skin near the wrist. In times past, it was fashionable for people to place a pinch of ground tobacco (snuff) in this depression and inhale it through their nostrils. Also known as the extrinsic thumb muscle group, the group has three muscles: the abductor pollicis longus, the extensor pollicis longus, and the extensor pollicis brevis. They begin on the ulna and radius bones, as well as on the interosseous membrane, and insert their tendons into the thumb bones. These tendons can be quite prominent on the surface when the thumb is extended in a “thumbs up” movement. These three muscles emerge in a diagonal direction from a location between the extensor digitorum and the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) muscles, unlike the muscles of the other layers, which descend in a vertical direction.

ANATOMICAL SNUFFBOX MUSCLES (EXTRINSIC THUMB MUSCLE GROUP)

Dorsal region of left hand, two views

|

Anatomical Snuffbox Muscles—Pronunciation Guide |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

abductor pollicis longus |

ab-DUCK-tor PAWL-lih-kiss LON-gus |

|

extensor pollicis brevis |

ek-STEN-sor PAWL-lih-kiss BREV-iss |

|

extensor pollicis longus |

ek-STEN-sor PAWL-lih-kiss LON-gus |

Also located in the deep layer of the lower arm are two other muscles: the supinator and the extensor indicis. The supinator (pron., SOO-pih-NAY-tor) muscle is covered by the superficial muscles of the extensor group and is not seen on the surface form. This two-headed muscle begins on the humerus (superficial head) and ulna (deep head) and inserts into the radius. As its name implies, the supinator rotates the lower arm in the action of supination.

The extensor indicis (pron., ek-STEN-sor IN-dih-siss) is a narrow fusiform muscle that runs parallel to one of the anatomical snuffbox muscles (extensor pollicis longus). It begins on the posterior surface of the ulna and the interosseous membrane and inserts into the index finger. The extensor indicis straightens the index finger (extension) at the MCP, DIP, and PIP joints and also helps straighten the hand (extension) at the wrist joint.

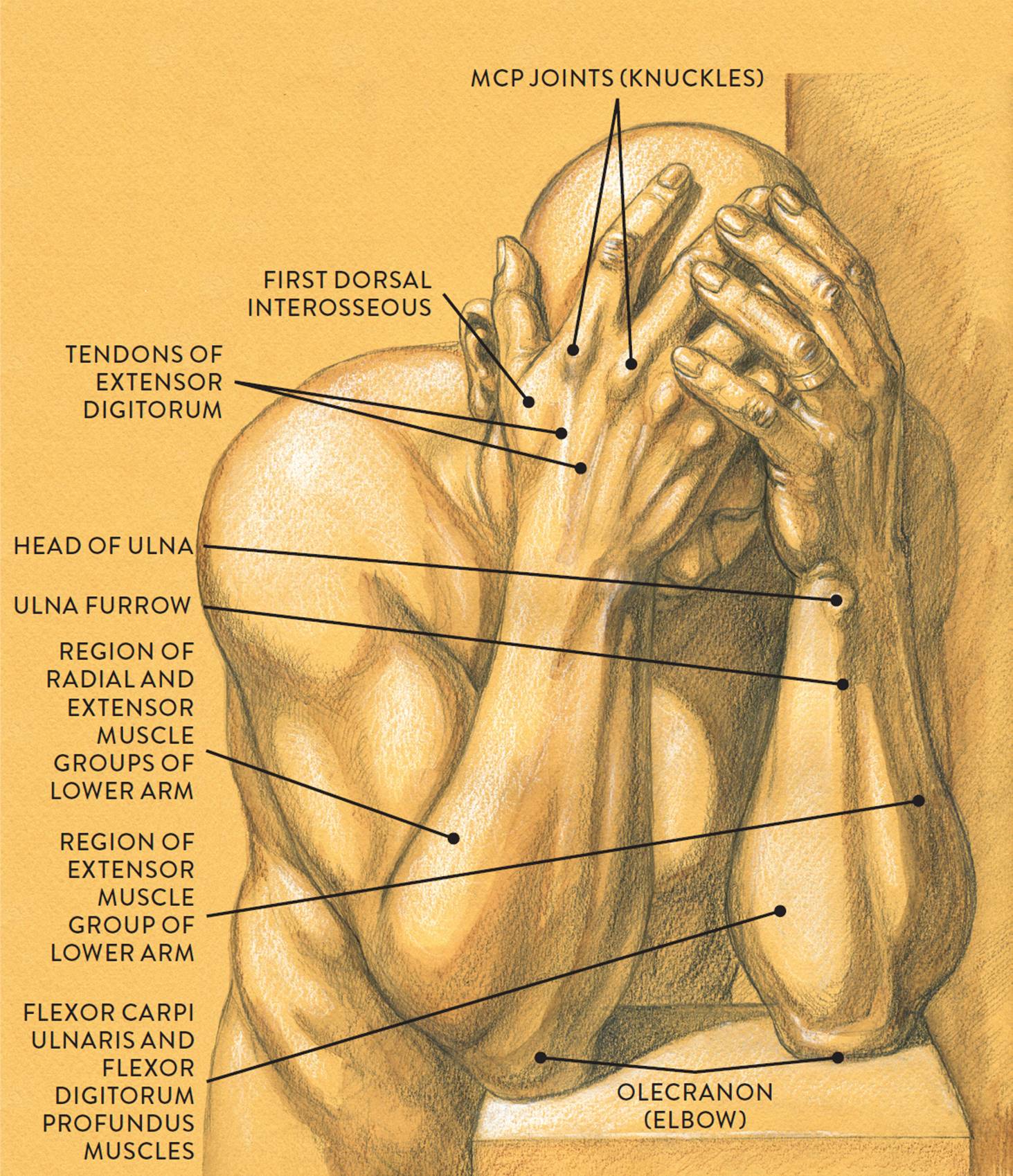

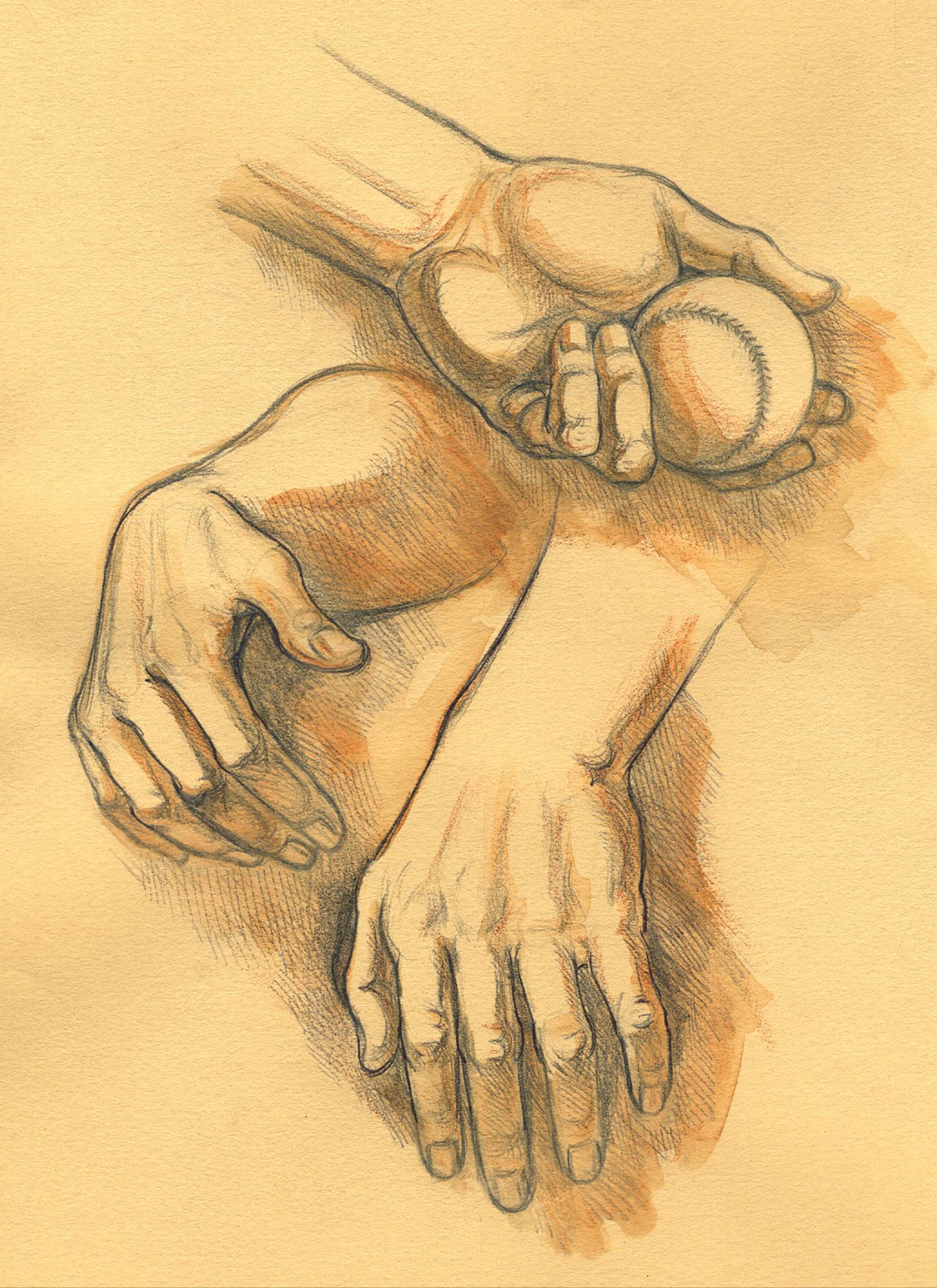

The life study Male Figure Clasping His Head in His Hands, shows a man with muscular lower arms and large hands. The accompanying muscle diagram reveals the positions of the lower arm muscles and their tendons in this pose.

MALE FIGURE CLASPING HIS HEAD IN HIS HANDS

Graphite pencil, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

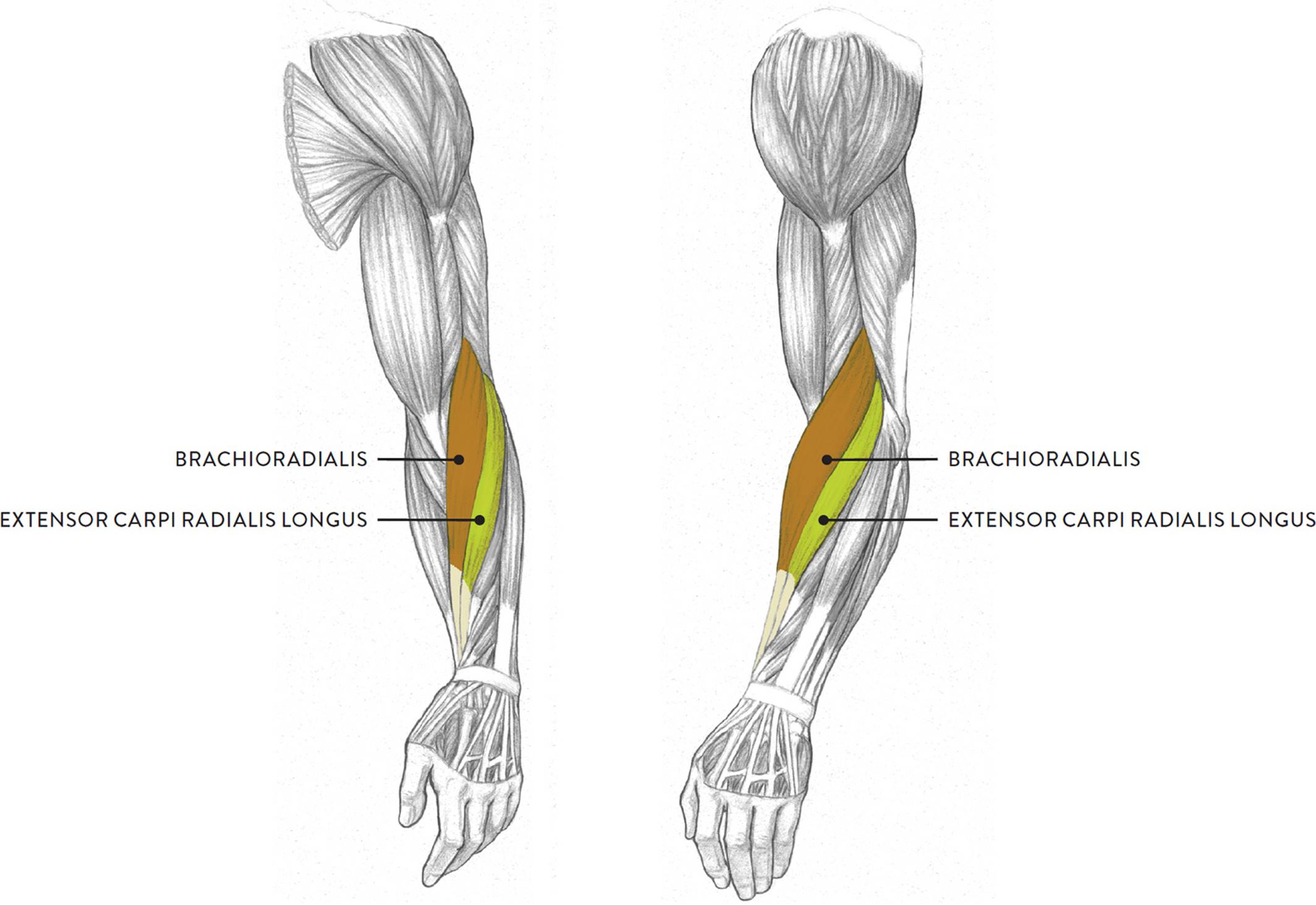

The Radial Muscle Group

Located in the superficial muscle layer of the lateral region of the lower arm, the radial muscle group provides an interesting transition between the upper arm and the lower arm. The radial group consists of two muscles: the brachioradialis and the extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL). Some anatomists add a third muscle, called the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), to the group, but since this muscle is rather slender and hard to detect on the surface form except in muscularly defined arms, we focus here on the other two muscles, shown in the lower drawing opposite. The radial group moves the lower arm (radius and ulna) at the elbow joint and the hand at the wrist joint.

RADIAL MUSCLE GROUP

Left upper and lower arm

LEFT: Anterior three-quarter view

RIGHT: Lateral view

The radial group serves as an important surface landmark for artists. Its rich, elongated shape begins on the outer part of the humerus and spirals downward along the radius bone toward the thumb side of the wrist. The shapes of these two muscles register as a single form on the average arm but as individual muscular ridges on the athletically defined arm.

The next drawing shows the right arm in the anatomical position, slowly rotating from the elbow joint to move the hand from a position in which the palm faces forward (supination) to a position in which the back of the hand faces forward (pronation). While the extensor carpi radialis longus does not assist in this movement, its presence in the radial group is important in that it clearly shows the spiraling action of the lower arm, along with the brachioradialis. The brachioradialis (formerly known as the supinator longus) participates in both pronation and supination. Other muscles participating in the action of pronation are the pronator teres and the pronator quadratus; the biceps brachii and the supinator muscles participate in the action of supination.

ROTATION (SUPINATION AND PRONATION) OF THE LOWER ARM

Right upper and lower arm, anterior view

The brachioradialis (pron., bray-kee-oh-ray-dee-AL-iss) is the most prominent shape of the radial group, appearing as a thick spiraling form near the elbow region. The brachioradialis begins on the outer side of the humerus and inserts by way of a long slender tendon into the lower portion of the radius. It is positioned between the extensor carpi radialis longus (of the radial muscle group) and the pronator teres and flexor carpi radialis (of the flexor muscle group). The brachioradialis helps bend the lower arm (flexion), and as stated above, it also assists in the supination and pronation of the lower arm. (The extensor carpi radialis longus has already been covered; see this page.)

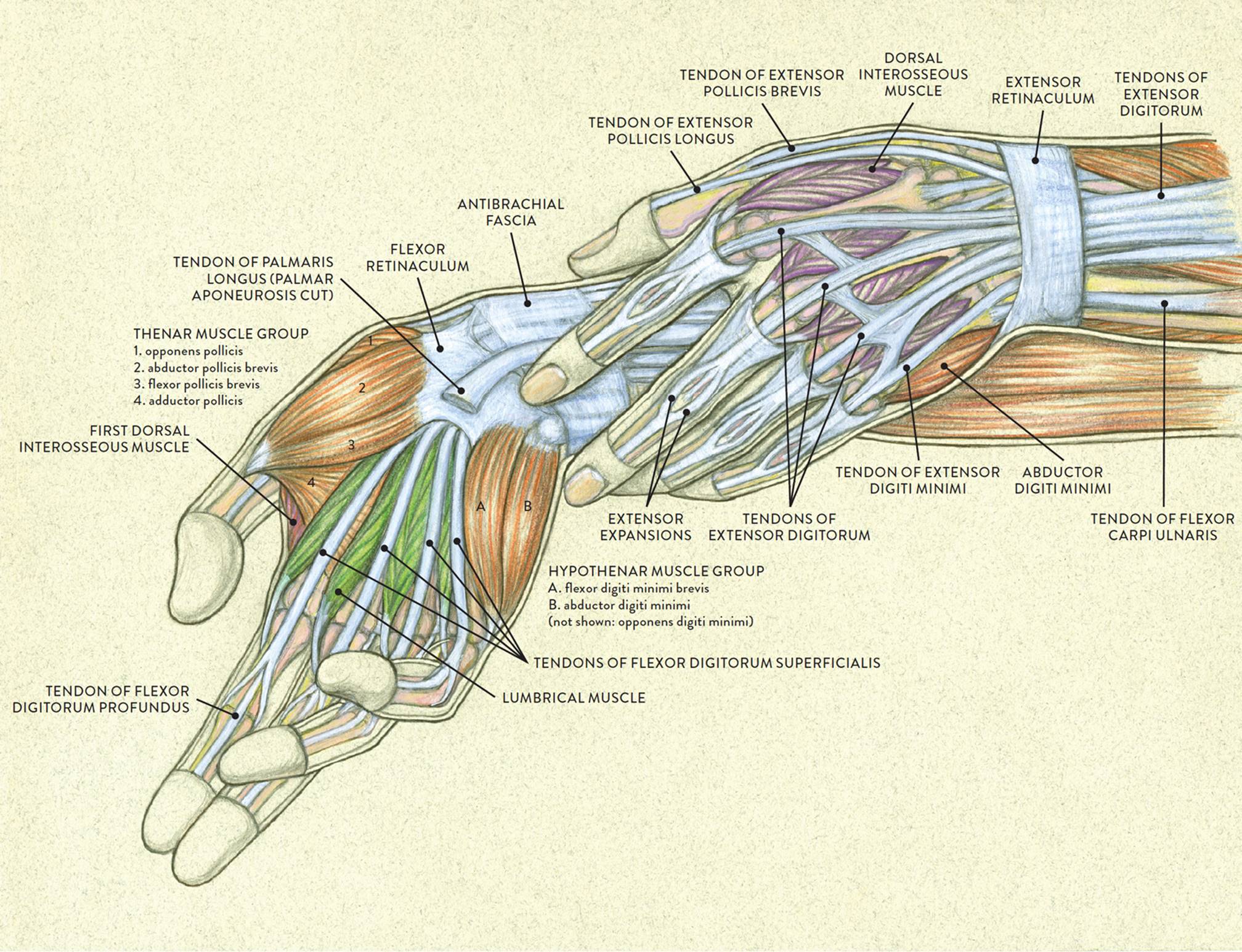

Muscles of the Hand

The two sides of the hand have differing and very distinctive characteristics. The palmar (palm) region contains rich muscle forms and fibrous padding, while on the dorsal (back) side the skin pulls tightly over bones and tendons, creating a streamlined appearance.

MUSCLES AND TENDONS OF THE HAND

LEFT: Palmar side of right hand, anterior view

RIGHT: Dorsal side of left hand, posterior view

The dorsal region of the hand contains only one group of muscles, the dorsal interosseous muscle group. Except for the first dorsal interosseous muscle, these muscles are hidden from view on the surface. The palmar region of the hand has two muscle groups: the thenar muscle group and the hypothenar muscle group.

There are no muscles below the metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP joints, or knuckles) of the hand; instead, the fingers (including the thumb) contain sheaths for the many tendons of the muscles that move them, which originate on the lower arm. The palm and the palmar side of the fingers, especially at their tips, also contain fibrous padding (see this page).

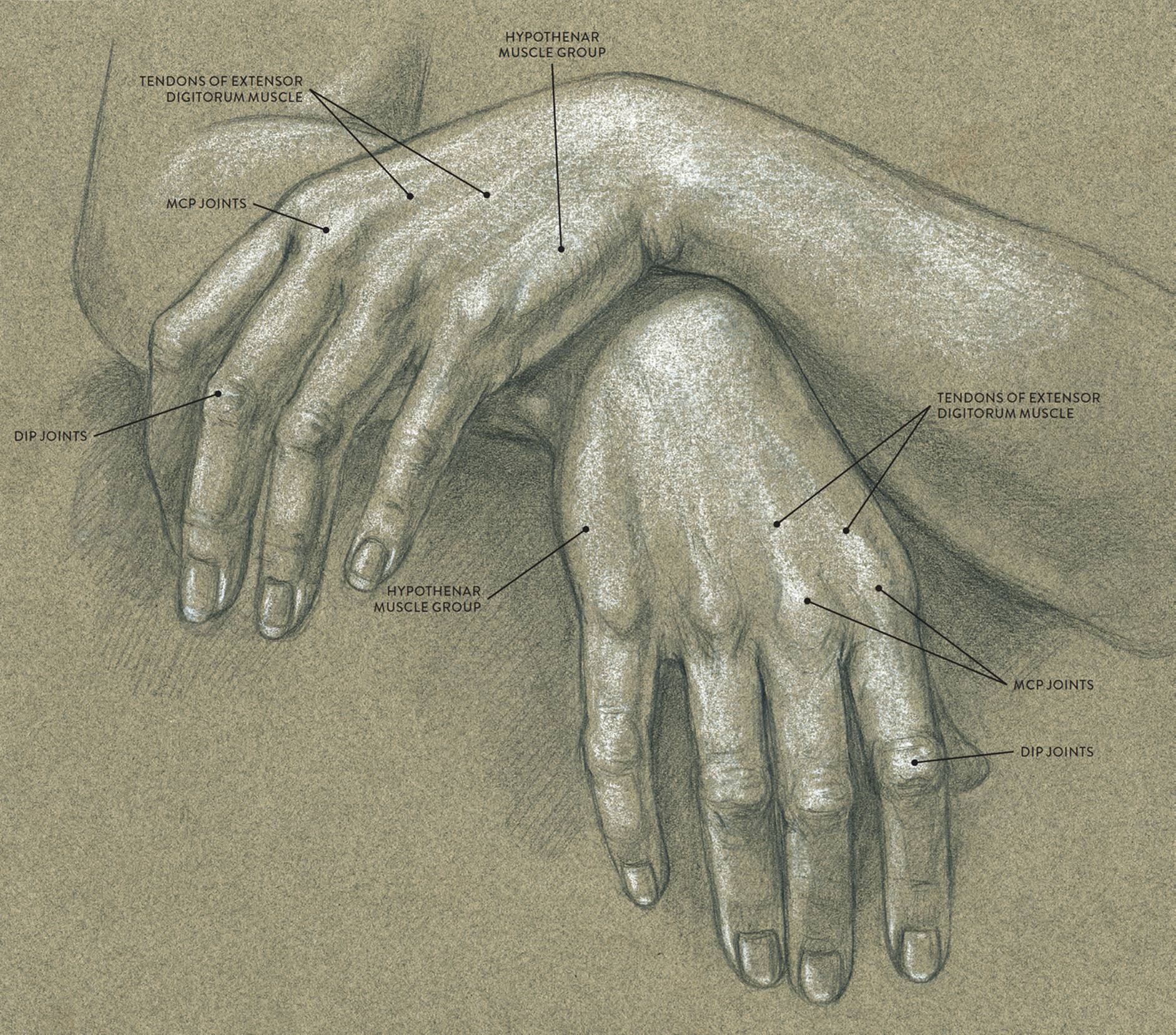

In the following drawing Study of Theresa’s Hands, you can see the tendons of the extensor digitorum muscle pulling toward the knuckles (MCP joints). On the outer sides of the hands the hypothenar muscle group is partly visible.

STUDY OF THERESA’S HANDS

Graphite pencil and white chalk on toned paper.

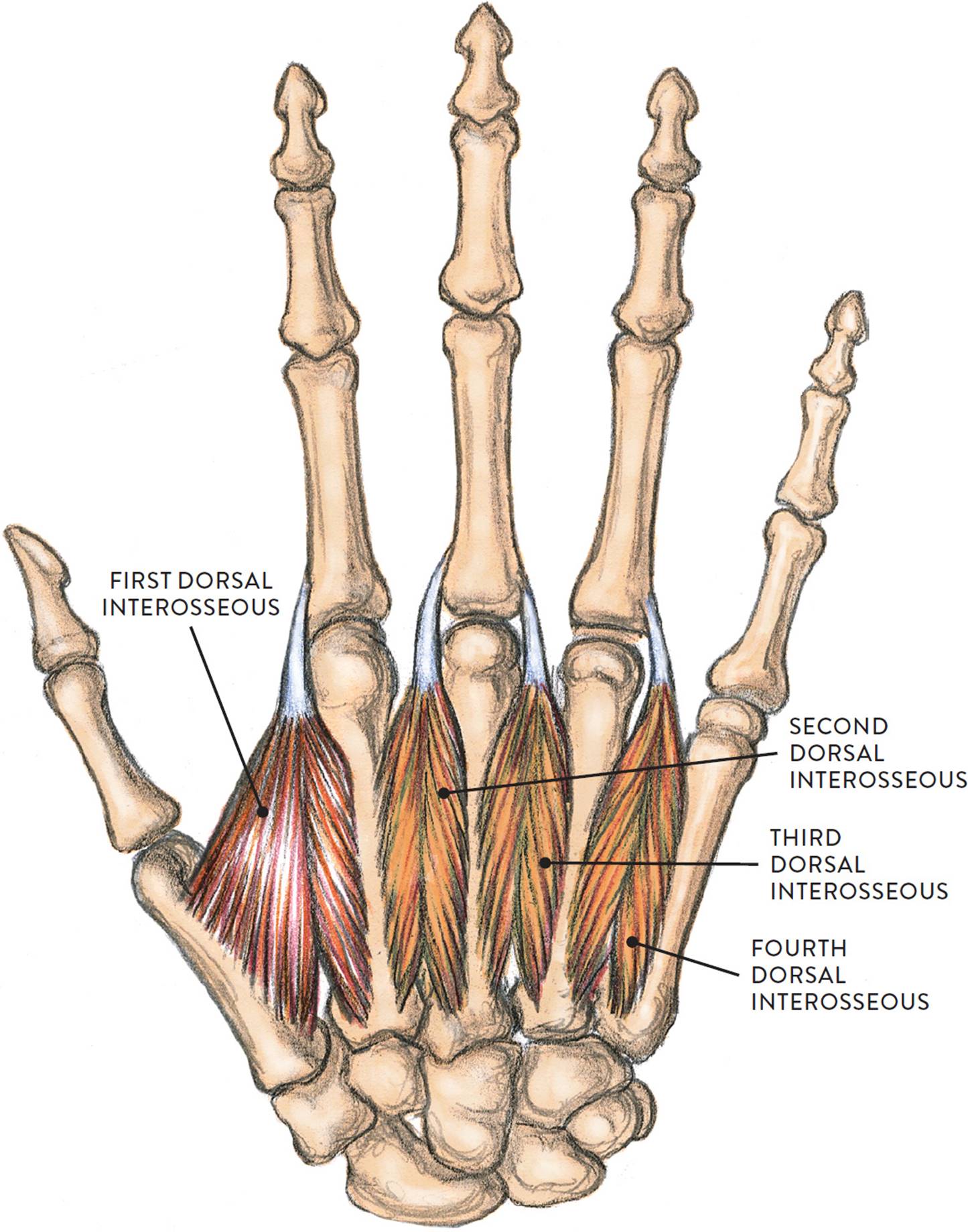

The Interosseous Muscle Group

The term interosseous (pron., in-tur-OSS-ee-us) means “between bones,” and that is exactly where the muscles of the interosseous group attach—between the metacarpal bones of the hand. There are two different groups of interosseous muscles, each containing four muscles. The dorsal interosseous muscle group shown in the following drawing, is located on the dorsal region of the hand; when these muscles contract they mainly spread the fingers apart (abduction). The palmar interosseous muscle group (not shown) is located on the palm side of the hand; when these muscles contract they return the spread fingers to their normal position (adduction).

DORSAL INTEROSSEOUS MUSCLE GROUP

Dorsal side of right hand, posterior view

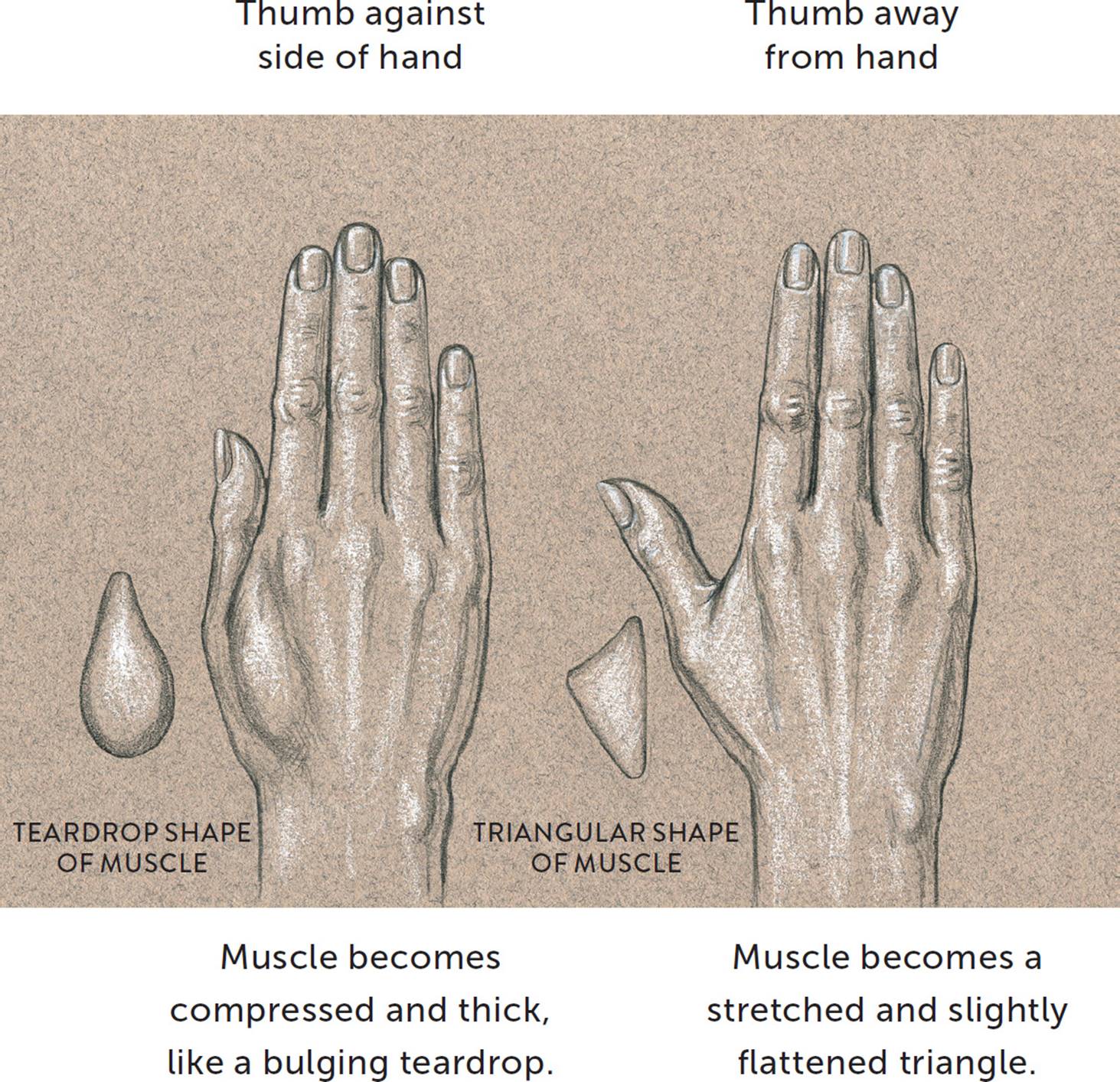

Only one interosseous muscle—the first dorsal interosseous—can be detected on the surface. The muscle fills the space between the metacarpal bone of the thumb and the metacarpal of the index finger. This triangular muscular space is sometimes referred to as the triangle of the thumb. The muscle changes shape depending on the placement of the thumb, as can be seen in the next drawing. It is easily seen when the thumb is pulled away from the hand in a sideways or downward direction. When the thumb is pressed against the side of the hand, the triangular shape becomes a thicker muscular mound—a teardrop shape on the dorsal side of the hand. Depending on how a person uses his or her hands, this shape may be large and quite thick or softer and subtler.

FIRST DORSAL INTEROSSEOUS MUSCLE—CHANGES IN SHAPE

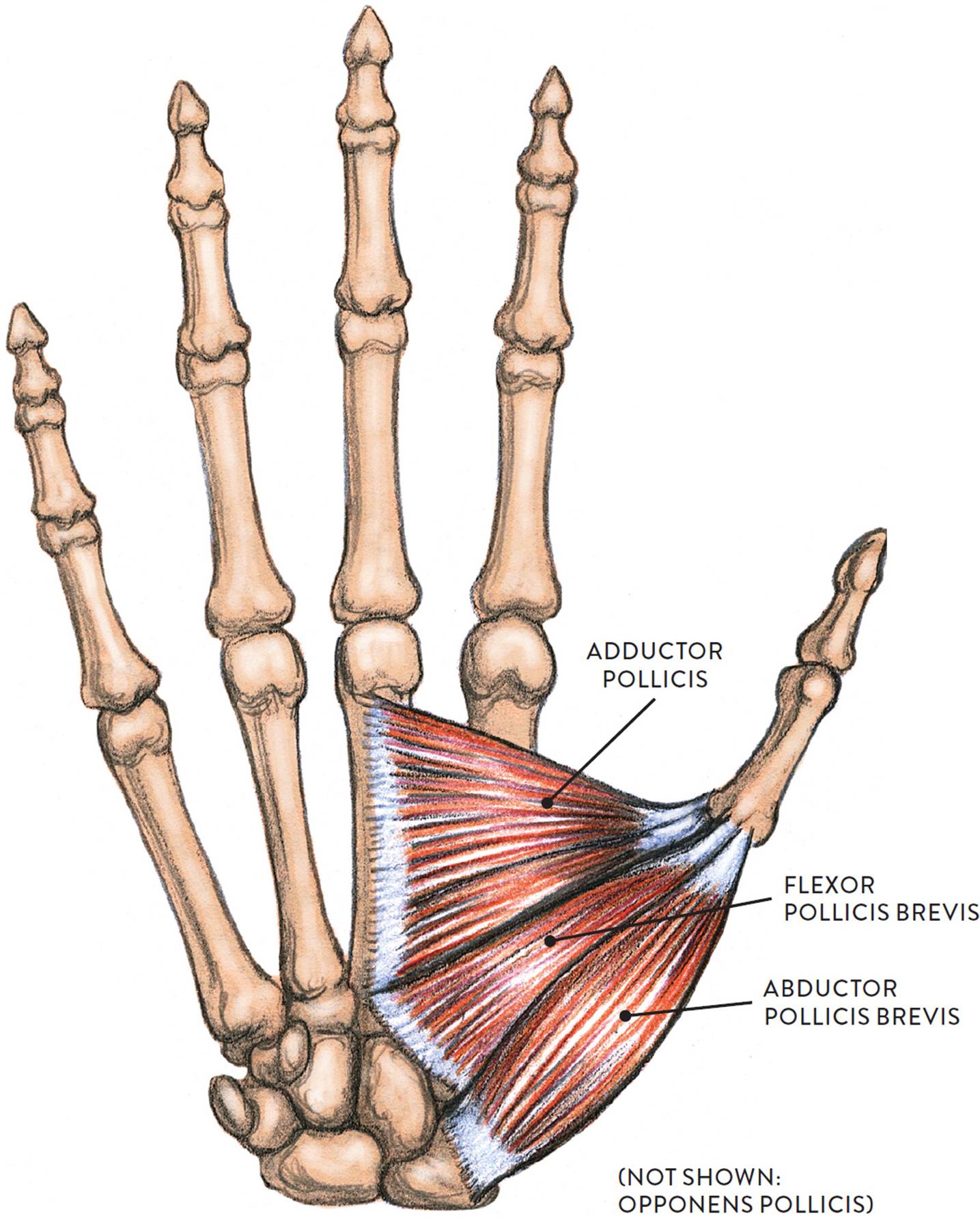

The Thenar Muscle Group

The thenar group consists of four muscles that form the rich muscular mound found on the palm side of the hand below the thumb. It is commonly referred to as the thumb prominence or thumb eminencebecause of its large, distinctive shape on the palm. The muscles of the thenar group are the adductor pollicis (adductor of the thumb), abductor pollicis brevis (short abductor of the thumb), flexor pollicis brevis (short flexor of the thumb), and the opponens pollicis (which enables the thumb to oppose the other fingers). All except the opponens pollicis are shown in the following drawing. The names of these muscles are actually easier to remember than you might think. The word pollicis, which appears in each, means “thumb,” and each name tells you how the muscle makes the thumb move: adduction, abduction, flexion, and opposition. The muscle group attaches on various carpal bones, metacarpal bones, and the bracelet-like fibrous sheathing of the wrist region called the flexor retinaculum.

THENAR MUSCLE GROUP

Palmar side of right hand

When drawing the palm side of the hand, you will usually detect the thenar group easily because of its large round shape positioned below the thumb. Since the muscles are covered with fibrous padding they usually cannot be distinguished individually, so it is best to approach the thenar group as a single form. The overall shape of the thumb and the thenar group is similar to that of a poultry drumstick, with the thumb representing the bony portion of the leg and the thenar muscles representing the thicker, meatier portion.

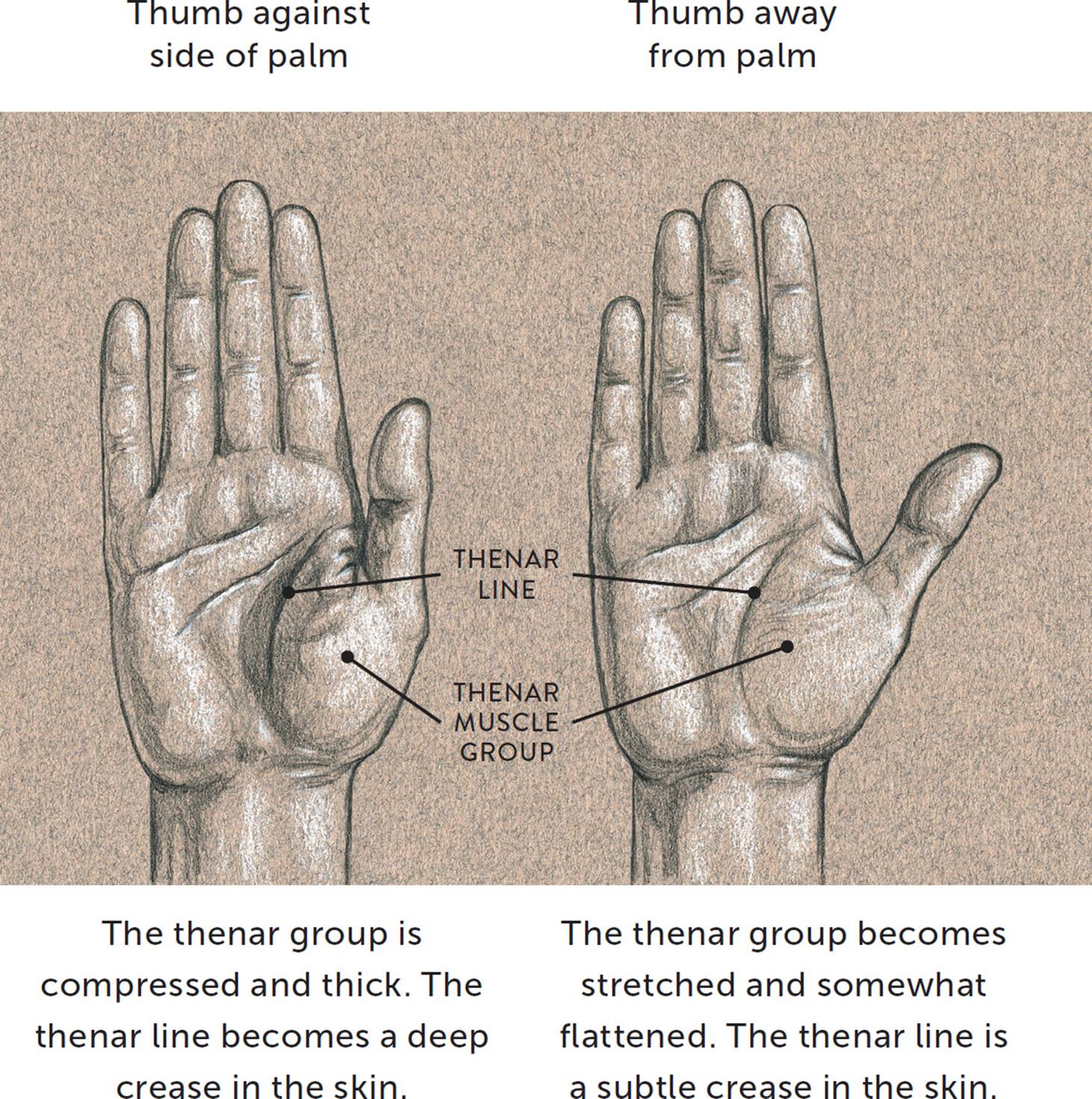

The shape and surface characteristics of the thenar group change depending on the placement of the thumb, as shown in the next drawing. When the thumb is positioned against the side of the palm, the thenar portion becomes compressed and thick, and the thenar line that travels around the outer perimeter of the thenar mass becomes a deep crease or fold within the skin. When the thumb is pulled away from the palm in a sideways direction, the thenar group becomes stretched and slightly flattened. The thenar line is still noticeable, but now as a subtle crease on the surface of the skin.

|

Thenar Group Muscles—Pronunciation Guide |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

adductor pollicis |

ah-DUCK-tor PAWL-lih-kiss |

|

abductor pollicis brevis |

ab-DUCK-tor PAWL-lih-kiss BREH-viss |

|

flexor pollicis brevis |

FLEK-sor PAWL-lih-kiss BREH-viss |

|

opponens pollicis |

oh-POE-nenz PAWL-lih-kiss |

THENAR MUSCLE GROUP—CHANGES IN SHAPE

The Hypothenar Muscle Group

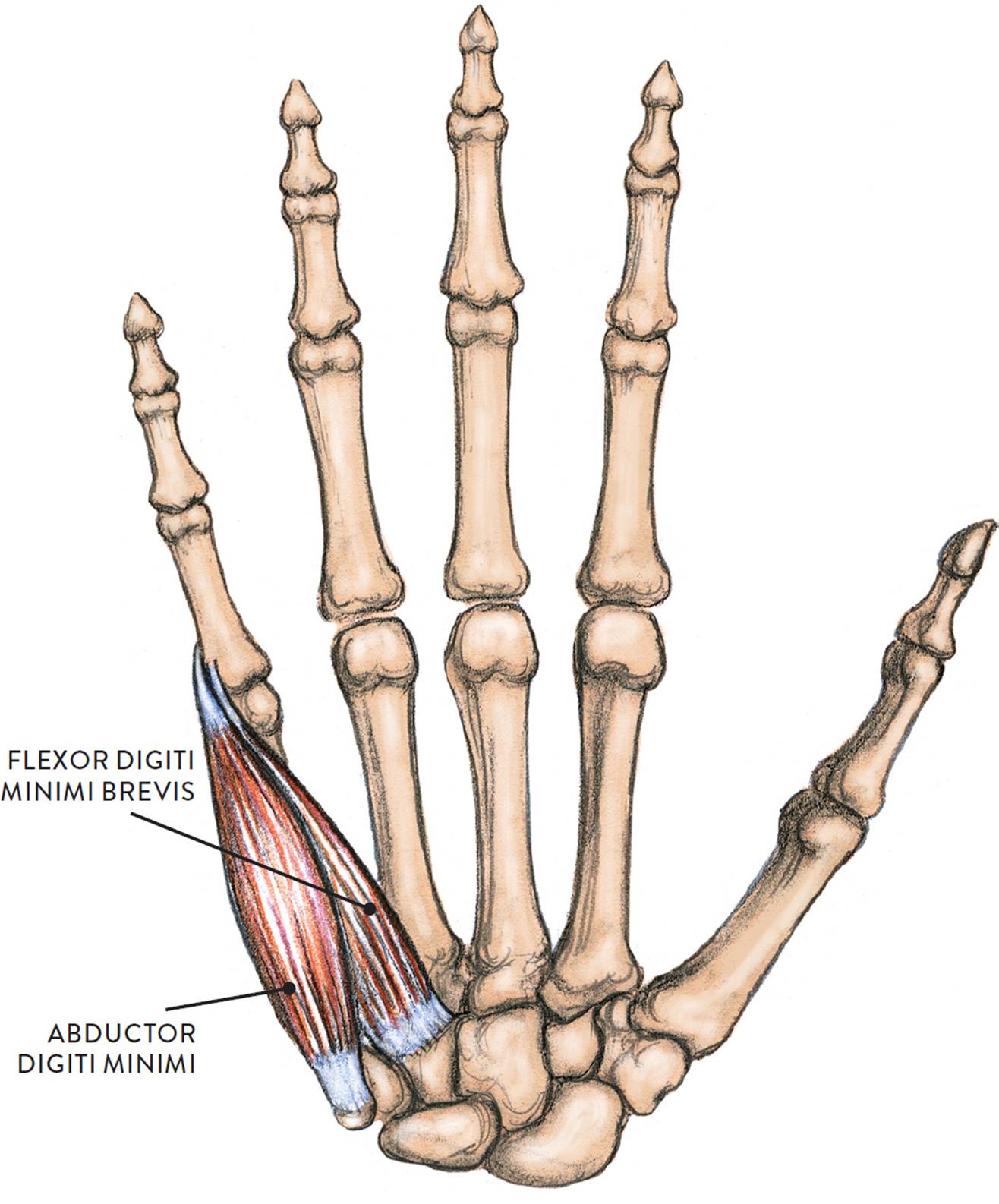

The hypothenar muscle group is an elongated teardrop form occupying the entire length of the side of the hand from the little finger to the heel of the hand. It consists of three muscles: the abductor digiti minimi, the flexor digiti minimi brevis, and the opponens digiti minimi. The abductor digiti minimi and flexor digiti minimi brevis are shown on this page (the opponens digiti minimi is not shown). As with the thenar group, it is not so hard to remember these muscles’ names, since the term digiti minimi means “little finger” and each muscle’s name tells you how it makes the little finger move: abduction, flexion, and opposition (in this case, enabling the little finger to oppose the thumb).

The opponens digiti minimi is positioned beneath the other two muscles and is hard to detect in most écorché views. Its shape, however, contributes to the fleshiness of the hypothenar group. The muscles are covered with fibrous padding, and so it is easier to see and depict them as a single form rather than individual muscles. The group is seen in palmar and side views of the hand on the little finger side.

HYPOTHENAR MUSCLE GROUP

(NOT SHOWN: OPPONENS DIGITI MINIMI)

Palmar side of right hand

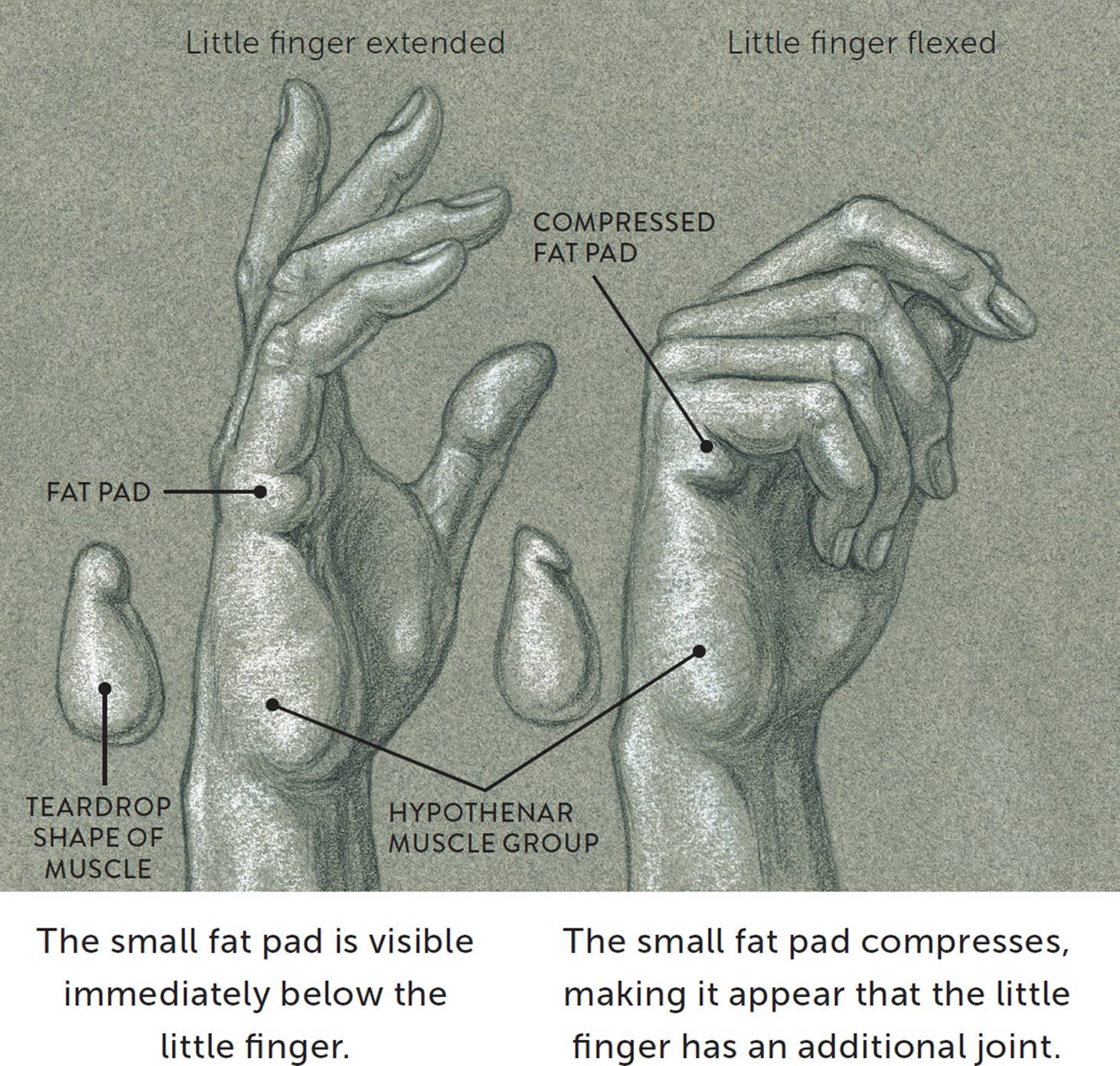

Immediately below the little finger is a small fat pad that is part of an elongated fat pad that runs horizontally across the palm at the base of the fingers. At the lower border of this elongated pad is a flexor crease called the distal palmar crease, or heart line. When the little finger bends, this outer portion of the fat pad form becomes compressed and the flexor crease is etched more deeply in the skin, creating the illusion that the little finger has an additional joint.

|

Hypothenar Group Muscles—Pronunciation Guide |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

abductor digiti minimi |

ab-DUCK-tor DIH-jih-tee MIN-ih-mee |

|

flexor digiti minimi brevis |

FLEK-sor DIH-jih-tee MIN-ih-mee BREV-iss |

|

opponens digiti minimi |

oh-POE-nenz DIH-jih-tee MIN-ih-mee |

The following drawing consists of two life studies of the right hand, showing the overall teardrop appearance of the hypothenar group. On one hand the fingers are extended but relaxed; on the other they are flexed, enabling you to see how the fat pad at the base of the little finger becomes compressed when the little finger bends.

HYPOTHENAR MUSCLE GROUP—TEARDROP SHAPE

Right hand, lateral view

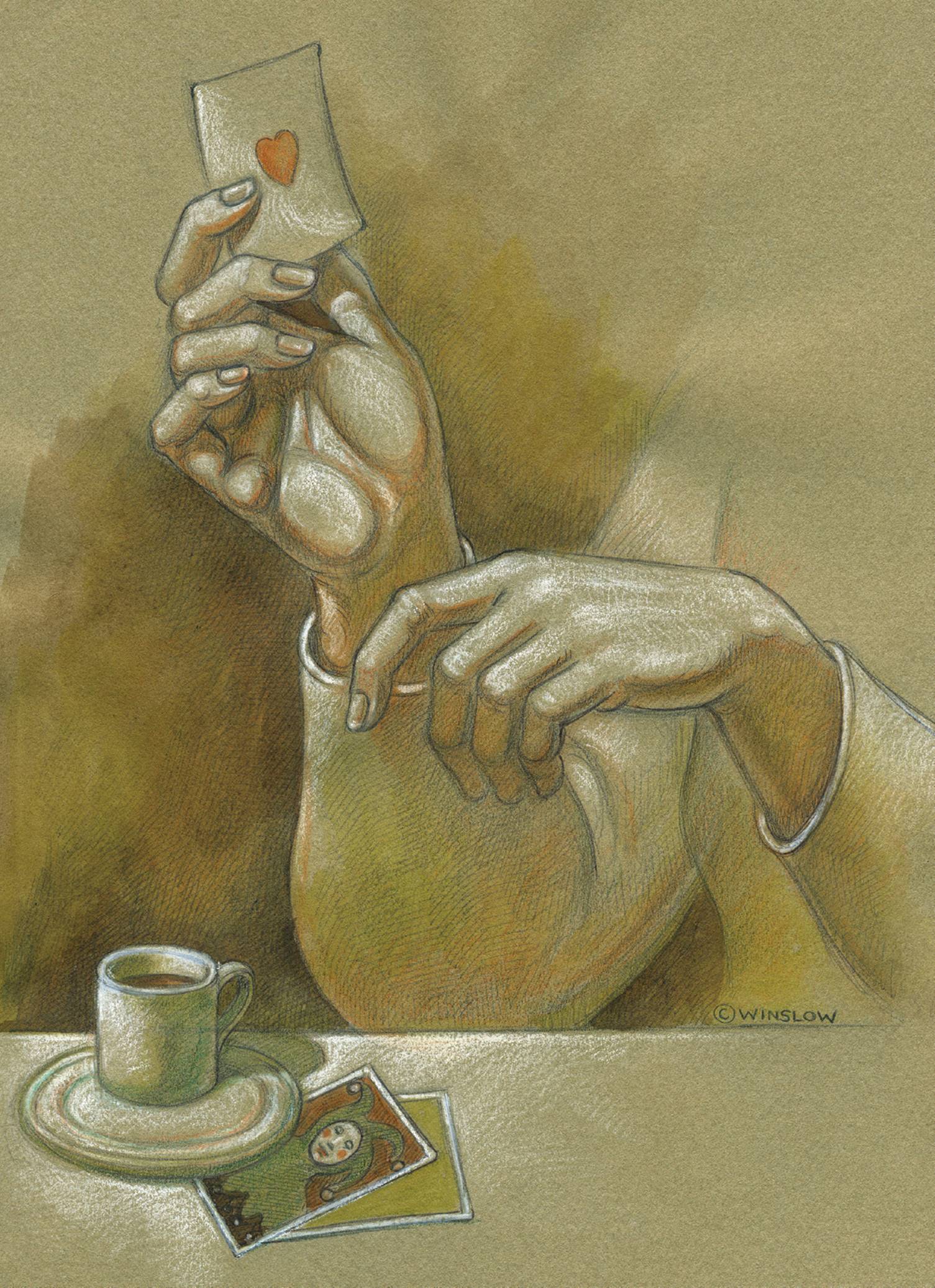

I recommend that you practice drawing hands in many positions—relaxed, dynamically positioned, or holding objects. After sketching the initial shape of the hand and fingers, add any anatomical forms (thenar and hypothenar muscle groups, triangle of the thumb, tendons, knuckles) that can be seen on the surface. Such studies can be done from your own non-drawing hand, other people’s hands, or photo sources. The drawings in Three Sketchbook Studies of Hands, were done from a model holding his hands in different positions.

STUDY OF TWO HANDS—ONE HOLDING AN ACE CARD

Graphite pencil, watercolor pencils, white chalk on toned paper.

THREE SKETCHBOOK STUDIES OF HANDS

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, and watercolor wash on toned paper.

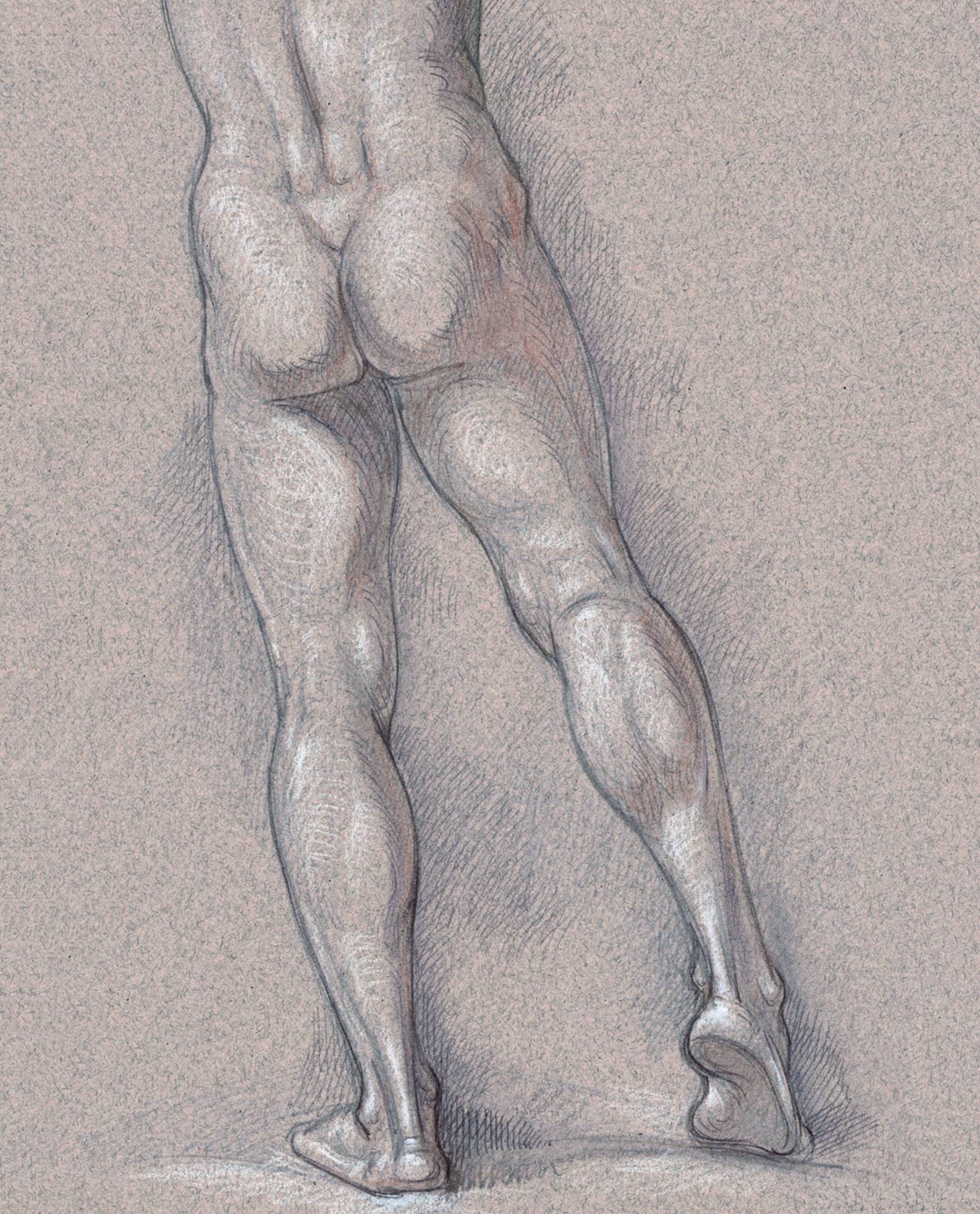

MALE FIGURE WITH RIGHT LEG POSITIONED ON THE BALL OF THE FOOT

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

Chapter 7

Muscles of the Leg and Foot

Together, the upper and lower legs and the feet make up half the length of the human figure. Legs come in all shapes and sizes, ranging from portly and stout, to the streamlined, almost emaciated legs of runway models, to the muscular legs of athletes.

Artists usually begin their study of the legs by focusing on the athletic type, because the shapes of the muscles are more easily seen. But most people’s legs are simple cylindrical forms with only a few distinct muscular shapes, such as the calf and quadriceps muscles. When depicting legs of this type, the emphasis can be placed on the rhythmic transition of forms throughout the leg. The drawings here provide a visual survey of the leg muscles.

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER AND LOWER LEG

LEFT: Lateral view

CENTER: Anterior view

RIGHT: Posterior view

MUSCLES OF THE UPPER AND LOWER LEG

Lateral view of a pair of legs

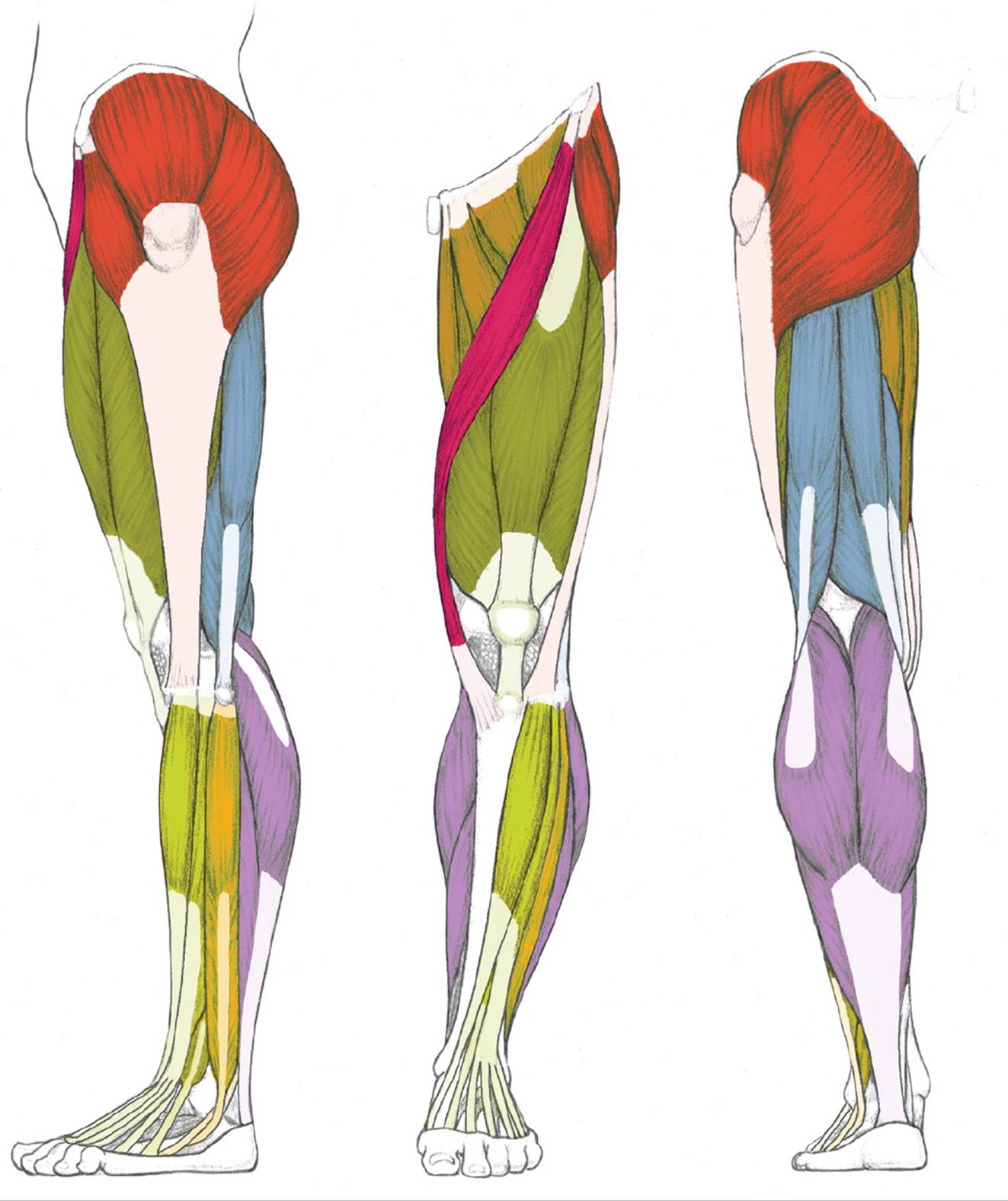

As with muscles of other regions of the body, the various muscles of the upper and lower leg can be divided into groups. The muscle groups of the upper leg region are the gluteal group, the quadriceps group,the adductor group,and the hamstring group. Those of the lower leg are the flexor group, the extensor group, and the peroneal group.

MUSCLE GROUPS OF THE UPPER AND LOWER LEG

LEFT: Lateral view

CENTER: Anterior view

RIGHT: Posterior view

GLUTEAL GROUP

QUADRICEPS GROUP

ADDUCTOR GROUP

HAMSTRING GROUP

SARTORIUS

EXTENSOR GROUP

PERONEAL GROUP

FLEXOR GROUP

Names of Leg and Foot Muscles

The names of leg and foot muscles provide clues to their location, function, shape, or size.

· Anterior means “of the front.”

· Intermedius means “in between.”

· Lateralis pertains to the outer (lateral) side of a body part.

· Medialis pertains to the median (as opposed to lateral) plane of a body part.

· Medius means “middle” or “in the middle.”

· Digiti and digitorum pertain to the toes (digits).

· Femoris pertains to the femur bone.

· Hallucis pertains to the great toe.

· Peroneus pertains to the fibula bone.

· Tibialis pertains to the tibia bone.

· Adductor pertains to moving a body part toward midline.

· Extensor pertains to stretching.

· Flexor pertains to bending.

· Rectus means “straight.”

· Brevis means “short.”

· Longus means “long.”

· Maximus means “greatest” or “largest.”

· Minimus means “smallest.”

· Vastus means “of great extent.”

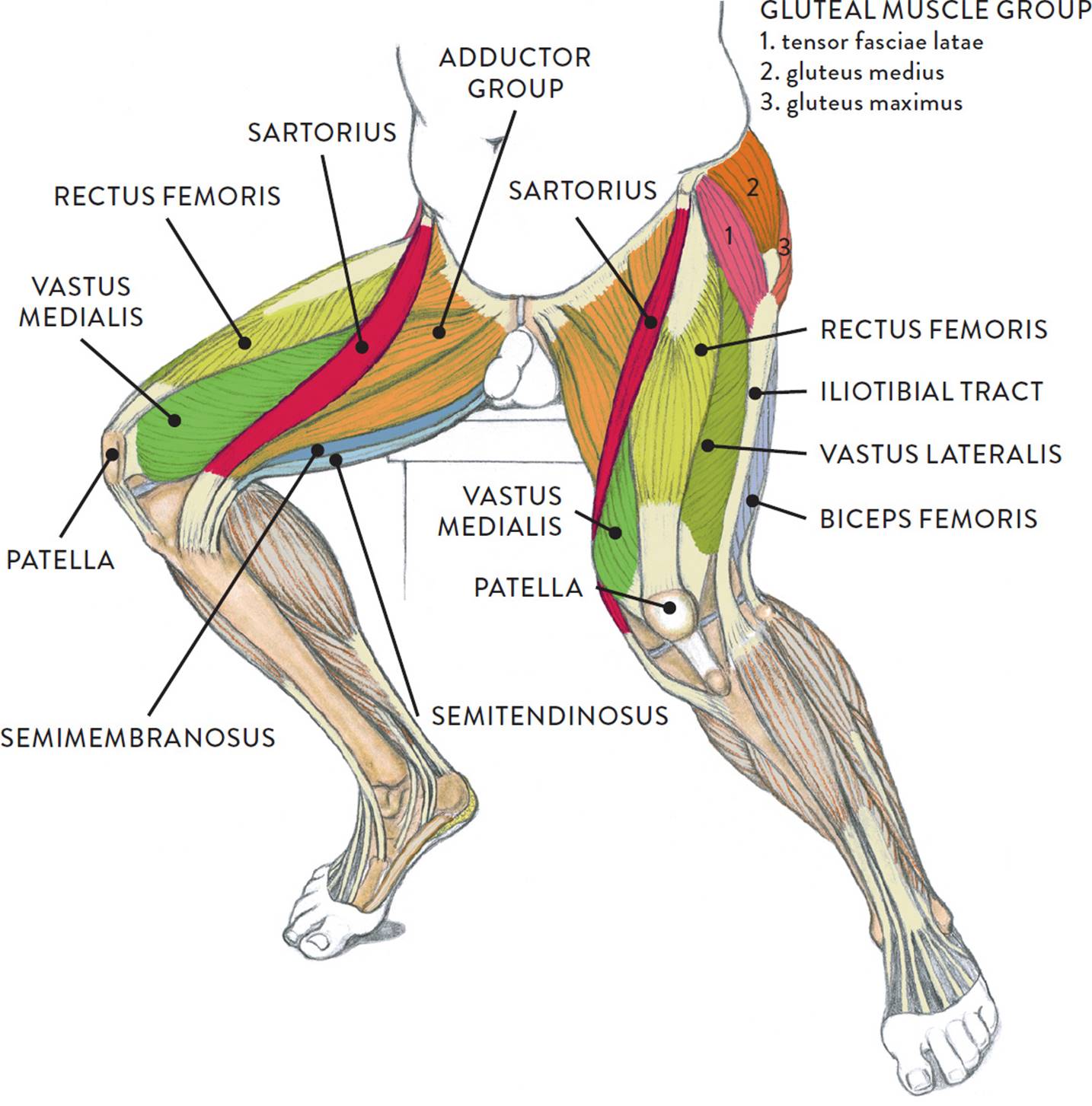

The Gluteal Muscle Group

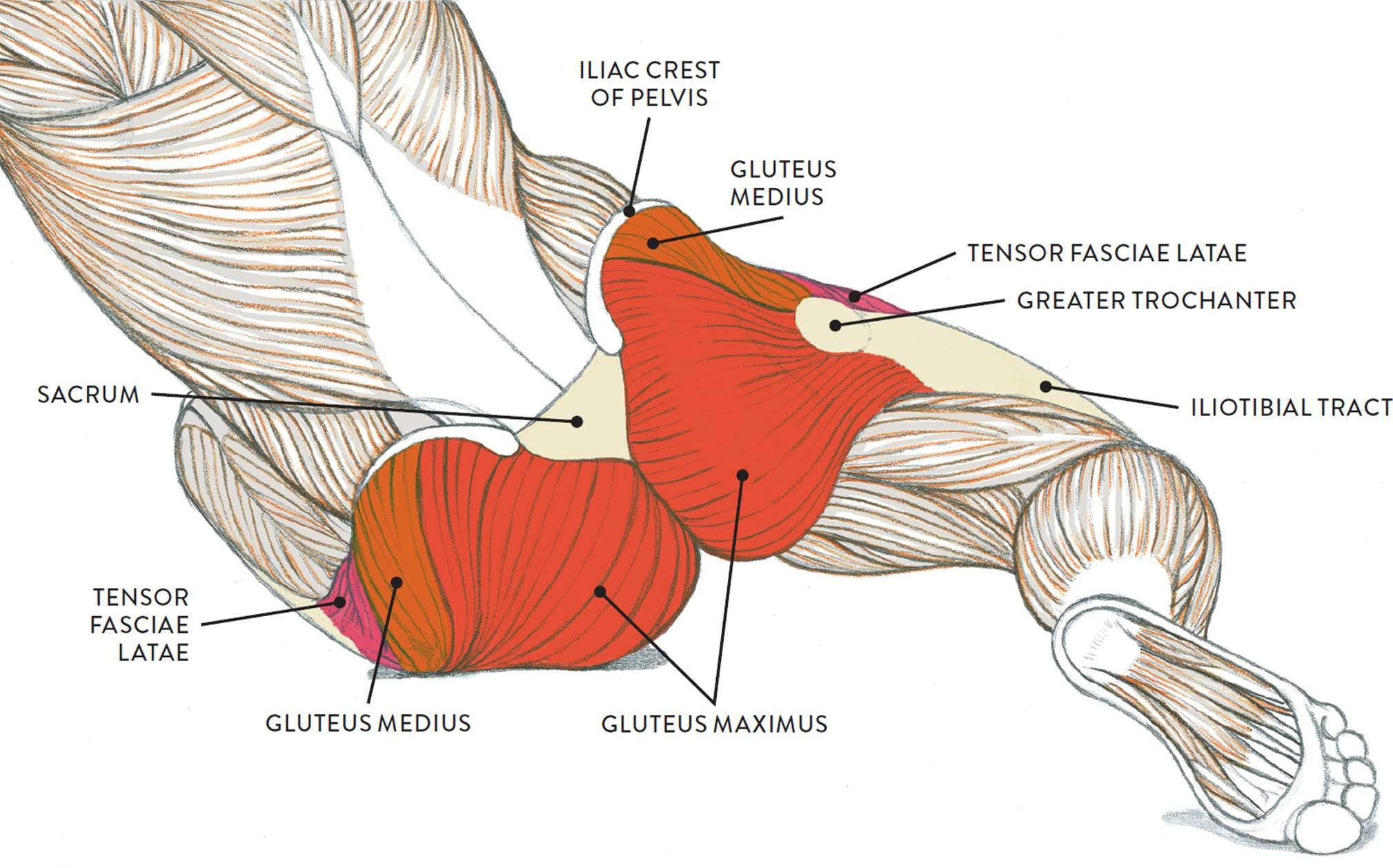

Let’s begin with a group of muscles that is part of both the torso and the legs: the gluteal (pron., GLOO-tee-ul) muscle group, shown in the following drawing. This group, occupying the lateral and posterior regions of the upper leg, primarily consists of four muscles that attach on the outer portion of the pelvis: the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae. The gluteus minimus is not seen on the surface form because it is beneath the gluteus medius, but the other three muscles do appear as three separate shapes on muscularly developed legs. If there is a predominant layer of fatty tissue in this region, however, the gluteal group is seen as a single large mass. The gluteal group moves the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint.

GLUTEAL MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, lateral (left) and posterior (right) views

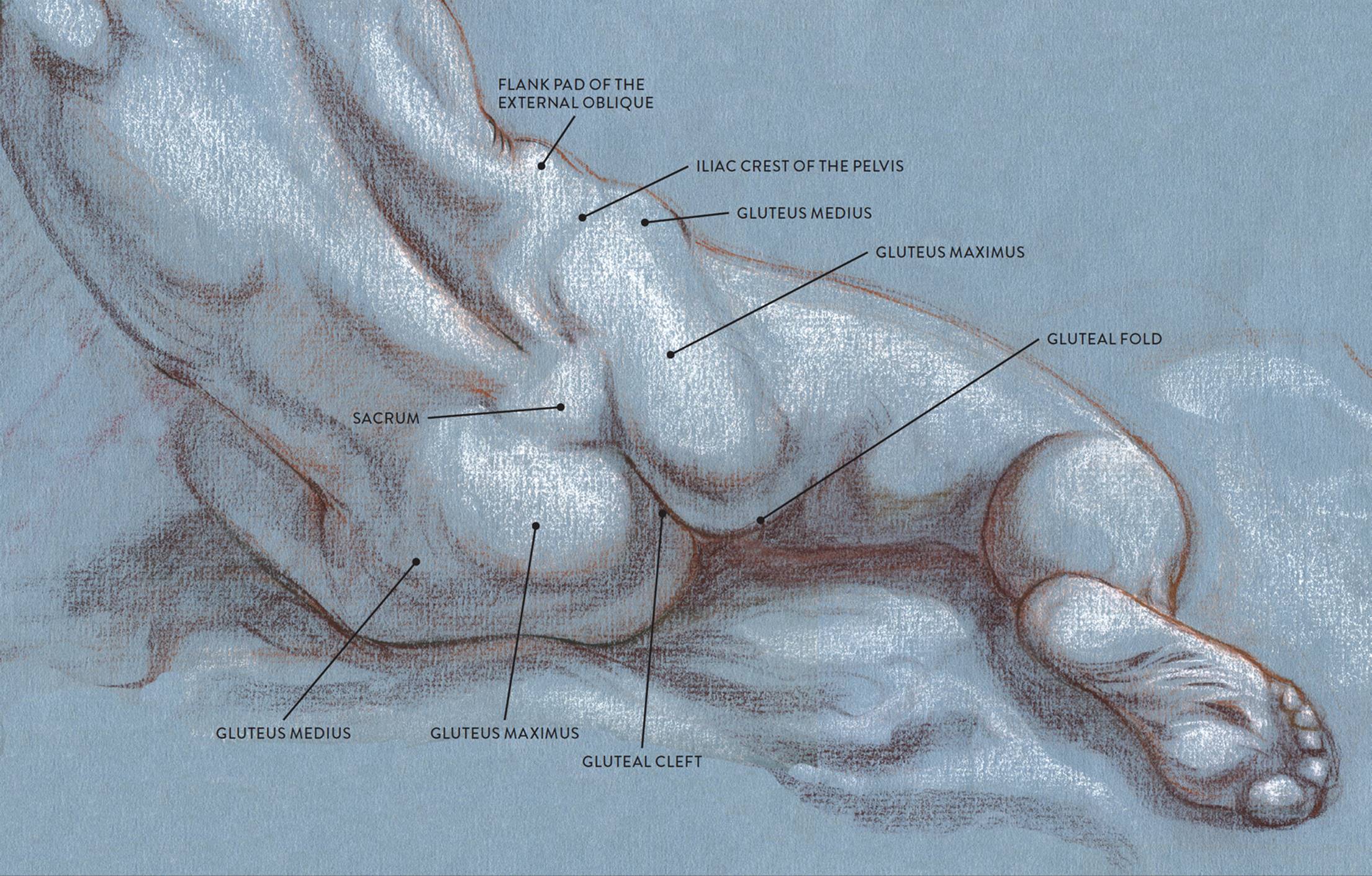

The following life study Male Figure Sitting on the Floor, shows a male figure whose hip muscles are well defined. The sacrum bone and the iliac crest of the pelvis—bony structures to which the muscles attach—are clearly seen. The accompanying muscle diagram reveals the positions of the muscles in this pose.

MALE FIGURE SITTING ON THE FLOOR

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils, white chalk on tone paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

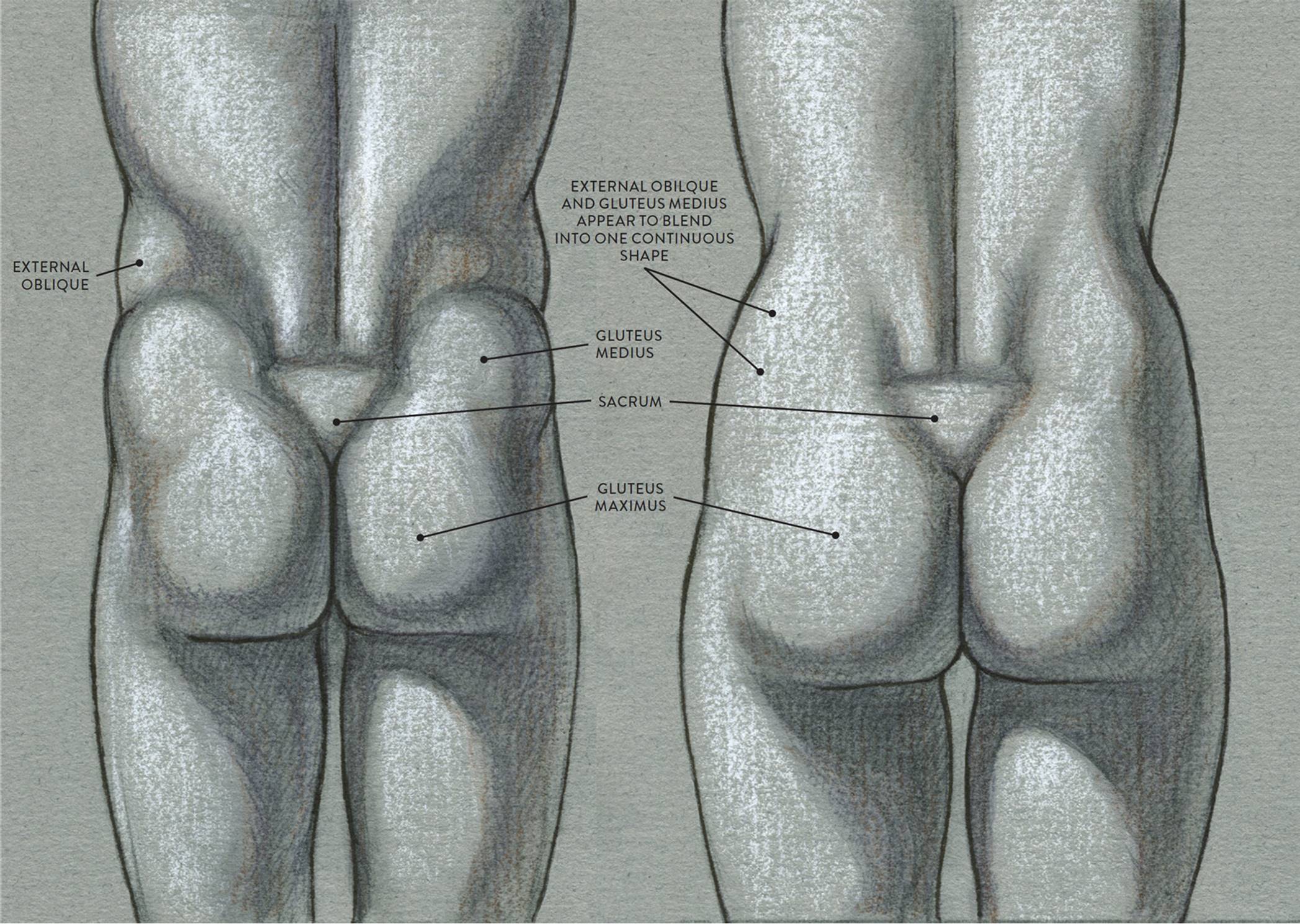

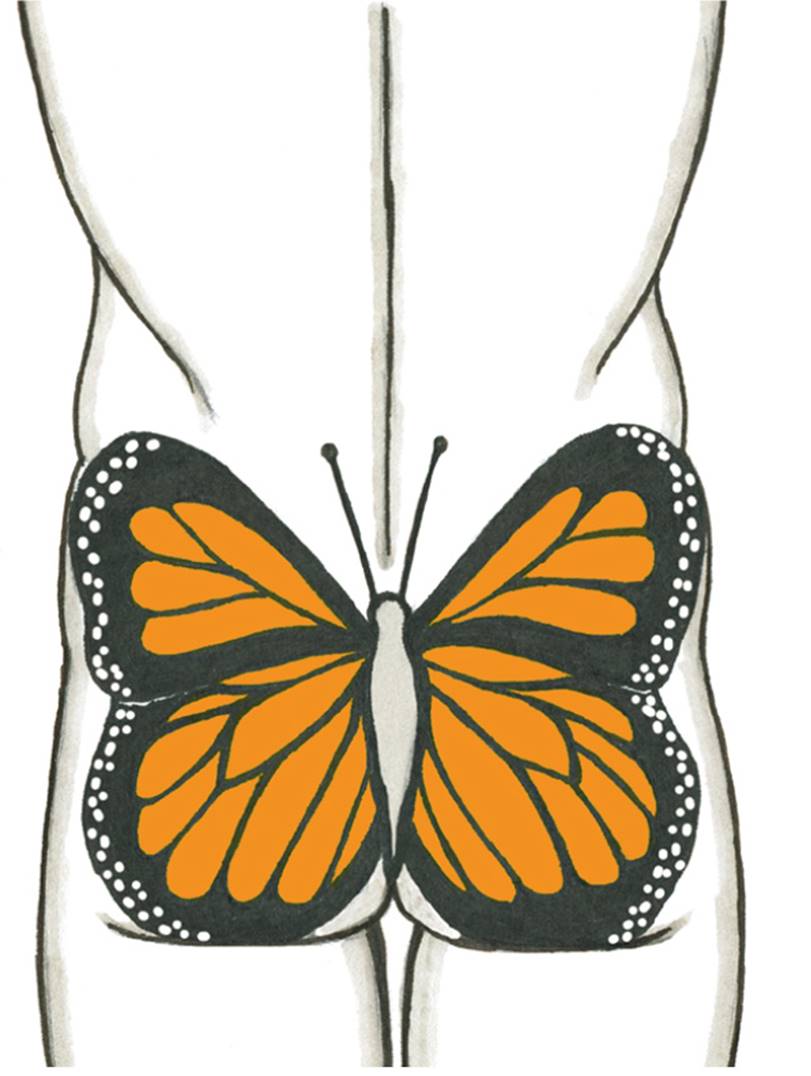

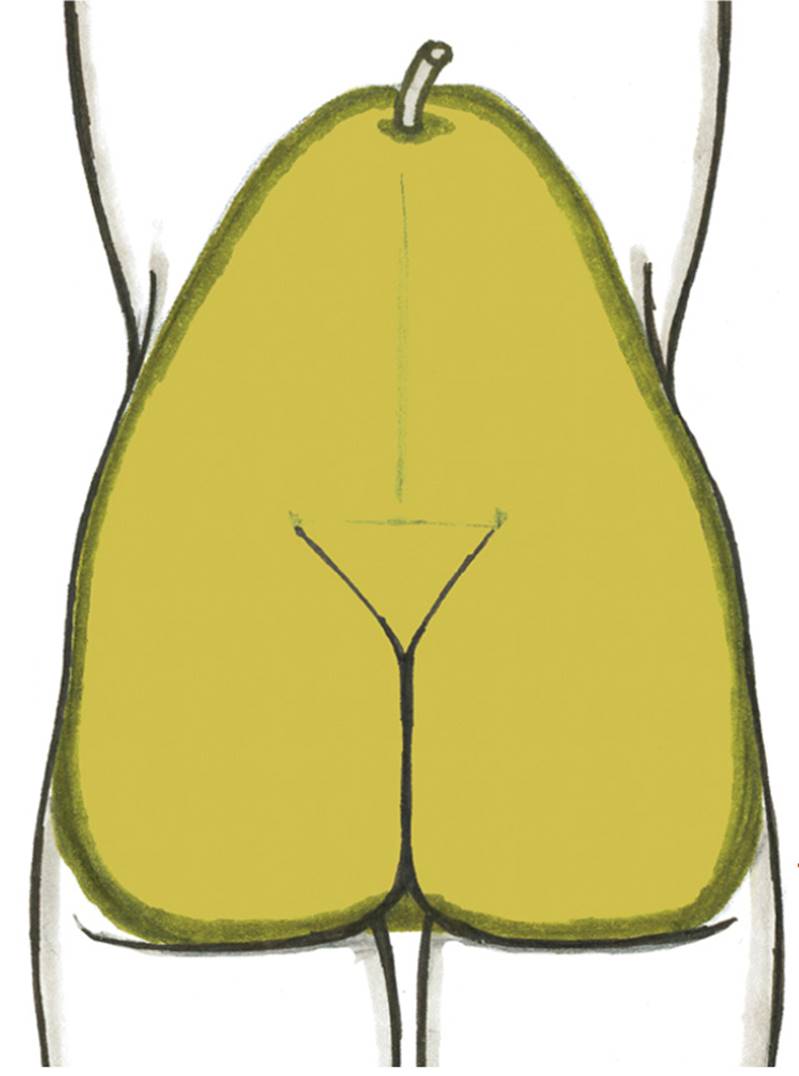

The sacrum bone is almost always noticeable, no matter what the body type, because it is not covered with muscles or substantial fatty tissue. It therefore serves the artist as a dependable visual landmark for the location of muscular forms. When viewed from the back, the shapes of the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius muscles are apparent on muscularly defined torsos, creating a butterfly shape. In torsos with a significant layer of fatty tissue, the gluteal muscles are softened into a single shape resembling a pear. In general, these shapes are characteristic of males and females, respectively, though there are many exceptions. You can use these shapes, shown in the drawings on this page, in gesture drawings, drawing them in very lightly to indicate the hips in an organic manner.

DIFFERENCES IN THE GLUTEAL MUSCLE GROUP—MALE AND FEMALE

LEFT: Male torso, posterior view

Muscle shapes are more apparent on the surface.

RIGHT: Female torso, posterior view

Muscles are covered by a thicker layer of subcutaneous tissue, softening the surface.

Male torso, posterior view

The combined forms of the gluteal muscles create a butterfly shape.

Female torso, posterior view

The gluteal muscle group and other soft-tissue forms of the female pelvis region are shaped like a pear.

The gluteus maximus (pron., GLOO-tee-us MACK-sih-mus) is the largest of the four gluteal muscles and dominates the hip region, especially in the posterior view. As the two muscles (left and right) swing away from each other near the bottom angle of the sacrum bone, they create a division called the gluteal cleft. When the upper leg is straight, a horizontal skin crease called the gluteal fold is seen on the lower border of the gluteus maximus; the fold disappears when the upper leg bends forward.

The gluteus maximus begins on the iliac crest of the pelvis and the outer edges of the sacrum and coccyx (tailbone) and inserts into the femur and the upper portion of the iliotibial tract. The iliotibial tract descends vertically down the outer side of the upper leg and eventually inserts into the lateral condyle of the tibia (large bone of lower leg). The gluteus maximus is the dominant extensor of the upper leg (femur). It bends the upper leg back from the hip joint (extension), and rotates the upper leg in an outward direction (lateral rotation).

The gluteus medius (pron., GLOO-tee-us MEE-dee-us) is a fan-shaped muscle that occupies the central portion of the pelvis bone. It is positioned between the tensor fasciae latae and gluteus maximus and appears as a prominent muscular bulge, especially when the muscle is contracting. This bulge should not be confused with the bulging form of the flank pad of the external oblique muscle, which is positioned directly above it on the side view of the torso. The iliac crest of the pelvis bone acts as a border between the two forms. If, however, there is substantial fatty tissue in this region, then the gluteus medius and the flank pad of the external oblique will appear as a single soft shape.

The gluteus medius begins on the outer surface on the ilium of the pelvis and inserts into the greater trochanter of the femur. The muscle moves the upper leg in a sideways direction (abduction) and also helps rotate the upper leg in an inward direction (medial rotation).

The gluteus minimus (pron., GLOO-tee-us MIN-ah-mus) is positioned on the central portion of the pelvis, beneath the gluteus medius. Even though this muscle is obscured from view by the gluteus medius, its fibers contribute to the bulging shape of the surface form in the side region of the pelvis. The muscle begins on the lower outer portion of the ilium and inserts on the greater trochanter of the femur. The gluteus minimus assists in the action of moving the upper leg away in a sideways direction (abduction) and helps rotate the upper leg inward (medial rotation).

The tensor fasciae latae (pron., TEN-sor FAA-shee-ee LAY-tee) is a teardrop-shaped muscle that begins on the ASIS of the pelvis and then flares slightly as it inserts into the fascia and upper portion of the iliotibial tract near the greater trochanter of the femur. Its shape is hard to detect on the surface form, although it can occasionally be seen as a small bulge in certain positions of the upper leg. When the leg is bent, or flexed, the tensor fasciae latae compresses so that the muscle fibers look as if they have a slight kink; on the surface, this compression appears as two egg-shaped forms. When the leg extends, the muscle stretches into a narrow oval. The tensor fasciae latae helps move the upper leg in a forward direction (flexion), moves the upper leg in a sideways direction (abduction), and rotates the upper leg in a inward direction (medial rotation). It also helps tense the iliotibial tract.

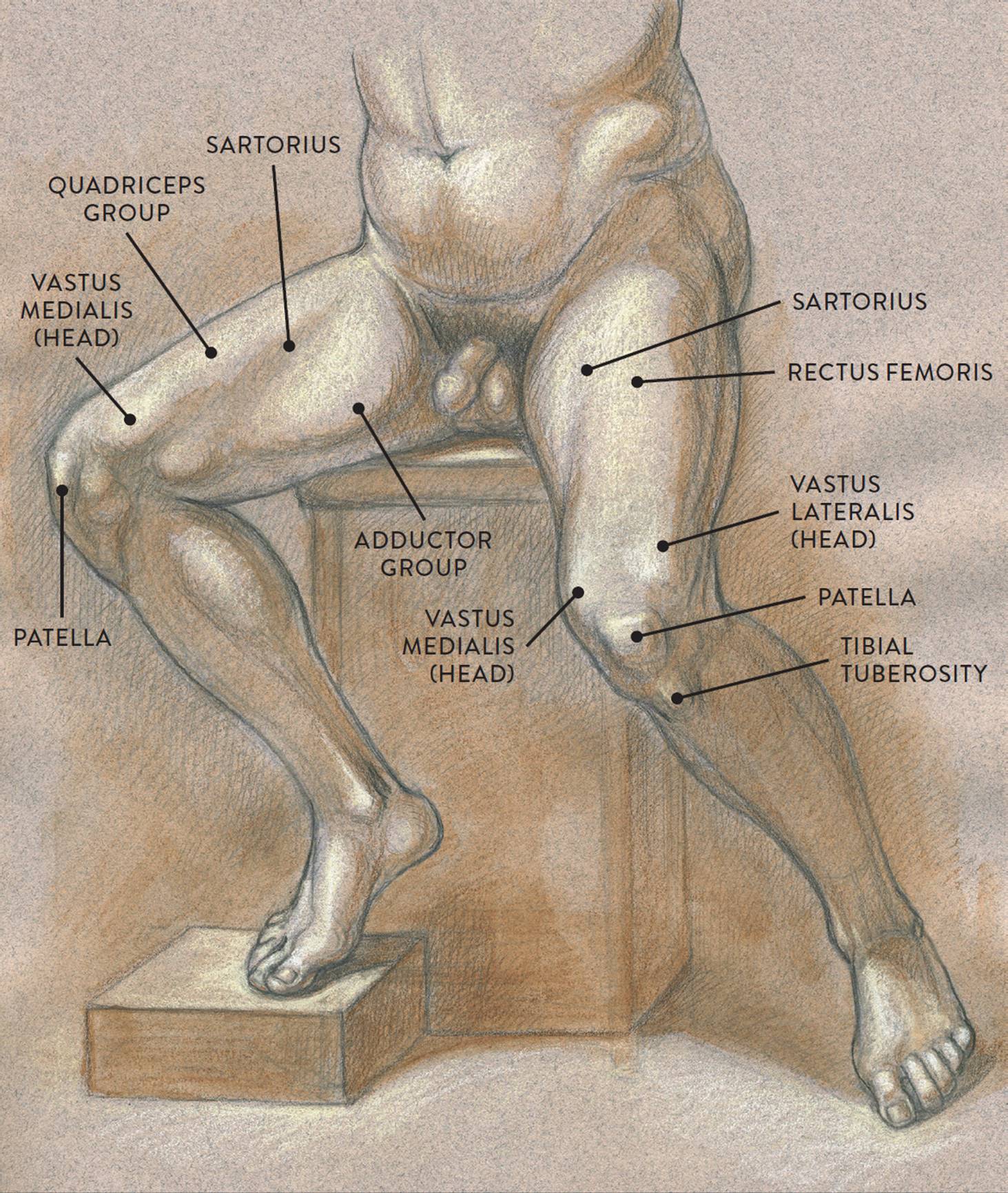

Three Muscle Groups of the Upper Leg, with the Sartorius Muscle

Besides the gluteal group (which is also part of the torso region), there are three main muscle groups of the upper leg. The most prominent group on the anterior region of the leg is the quadriceps muscle group, also known as the quadriceps femoris, quads, or extensor group of the upper leg. Located on the medial (inner) portion of the upper leg is the adductor muscle group, sometimes referred to as the inner thigh muscles. Occupying the posterior region of the upper leg is the hamstring muscle group, also called the flexor group of the upper leg. An elongated muscle called the sartorius, which does not belong to any group, lies between the quadriceps and adductor groups. These muscles move the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint and the lower leg (tibia and fibula) at the knee joint.

The Quadriceps Muscle Group

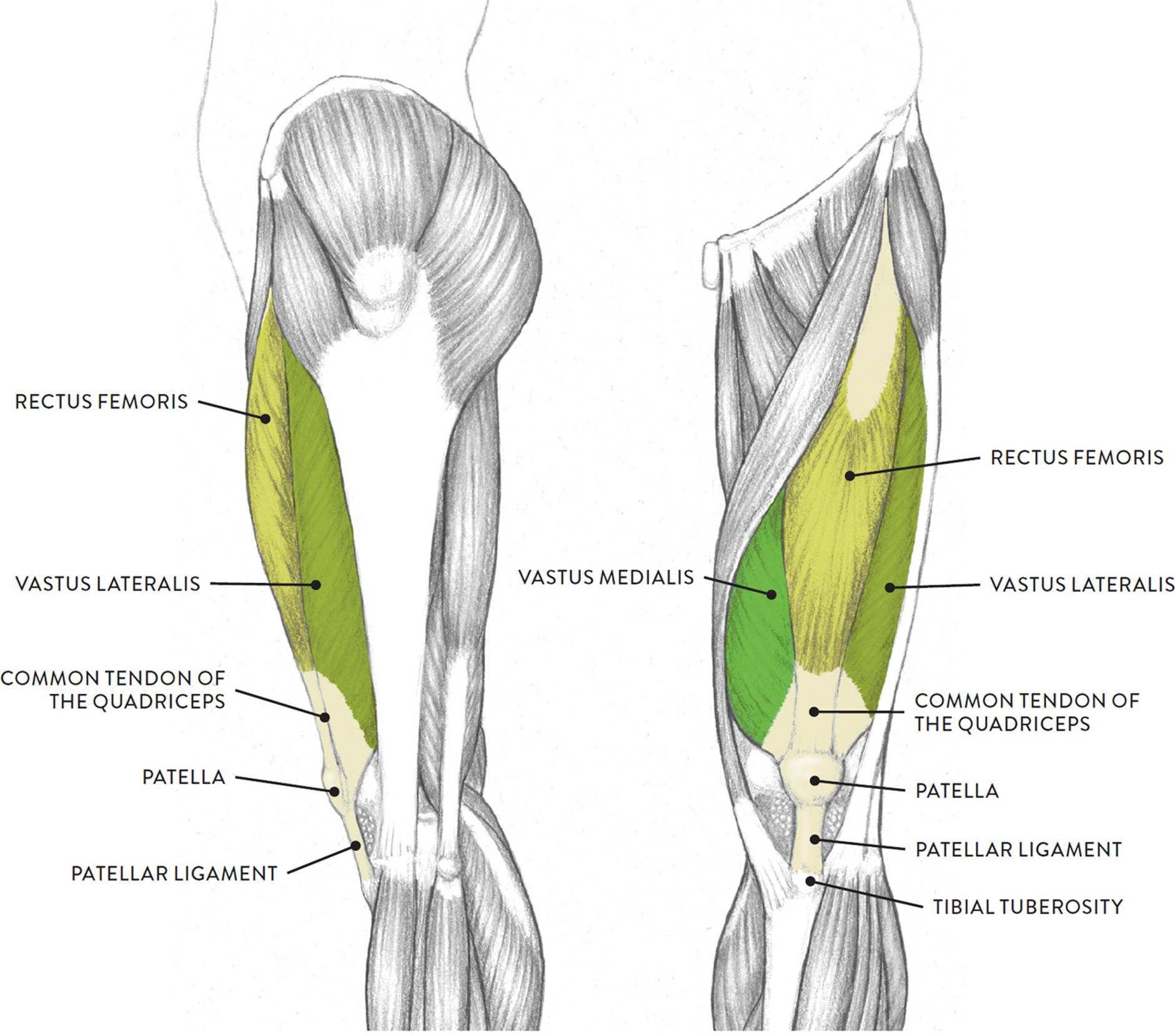

The main muscle group on the anterior region of the upper leg is the quadriceps group (pron., KWAHD-drih-seps), shown in the drawing opposite. The term quadriceps means “four-headed” (Latin: quad = four, ceps = head). Some experts consider the quadriceps to be one muscle consisting of four parts, while others define the quadriceps as a group of four individual muscles. The latter, more traditional definition is the one I follow here.

QUADRICEPS MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

Three of the muscles (vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and rectus femoris) are apparent on the surface form in muscular types, while the fourth (vastus intermedius) is always obscured from view. The borders of the quadriceps are the sartorius muscle (medial side) and the tensor fasciae latae muscle with the iliotibial tract (lateral side). The quadriceps muscles move the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint and the lower leg at the knee joint.

Each muscle of this group starts at four different locations on the femur and pelvis, and the muscles merge into one common tendon (tendon of quadriceps) that inserts into the patella (kneecap). The tendon continues past the patella to attach into the tibial tuberosity of the tibia; this latter segment of the tendon is usually called the patellar ligament. When depicting the knee region, it is essential for artists to locate the patella because it is the main anchoring site for the quadriceps muscle group.

The next life study, Seated Male Figure with Robust, Muscular Legs, focuses on the muscular forms of the anterior region of the upper legs. In it, you can see the quadriceps group, the adductor group, and the sartorious muscle between them. The accompanying muscle diagram further reveals the positions of the muscles in this pose.

SEATED MALE FIGURE WITH ROBUST, MUSCULAR LEGS

Graphite pencil, watercolor wash, and cream and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The rectus femoris (pron., RECK-tus FEM-o-riss, RECK-tus FEE-mor-iss, or RECK-tus fee-MORE-iss) occupies the central portion of the quads and is positioned over the vastus intermedius. The muscle begins near the ASIS of the pelvis directly above the acetabulum (hip socket). It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon, which continues on to the tibial tuberosity of the tibia. The rectus femoris helps straighten the lower leg at the knee joint (extension) and also helps bend the femur in a forward direction at the hip joint (flexion).

The vastus lateralis (pron., VAS-tus laa-ter-AL-iss) produces the thick mass of muscular form on the outer part of the upper leg and also forms a prominent bulge (the outer head) near the kneecap when the quadriceps muscle contracts. The muscle begins on the posterior side of the femur, near the greater trochanter. It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon. The vastus lateralis straightens the lower leg at the knee joint (extension).

The vastus medialis (pron., VAS-tus mee-dee-AL-iss) is positioned on the medial portion (inner thigh) of the upper leg. When this muscle contracts, it produces a rich bulge near the kneecap, toward the inner part of the leg. The muscle begins on the posterior side of the femur, near the lesser trochanter. It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon. The vastus medialis helps straighten the lower leg at the knee joint (extension) and also helps stabilize the patella.

The vastus intermedius (pron., VAS-tus in-ter-ME-de-us) is positioned between the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis. This muscle is usually not seen on the surface form because the rectus femoris muscle is positioned on top, obscuring it from view. The muscle begins on the front and side portions of the femur. It inserts into the patella by way of the common quadriceps tendon. Like the other vastus muscles, the vastus intermedius helps straighten the lower leg from the knee joint (extension).

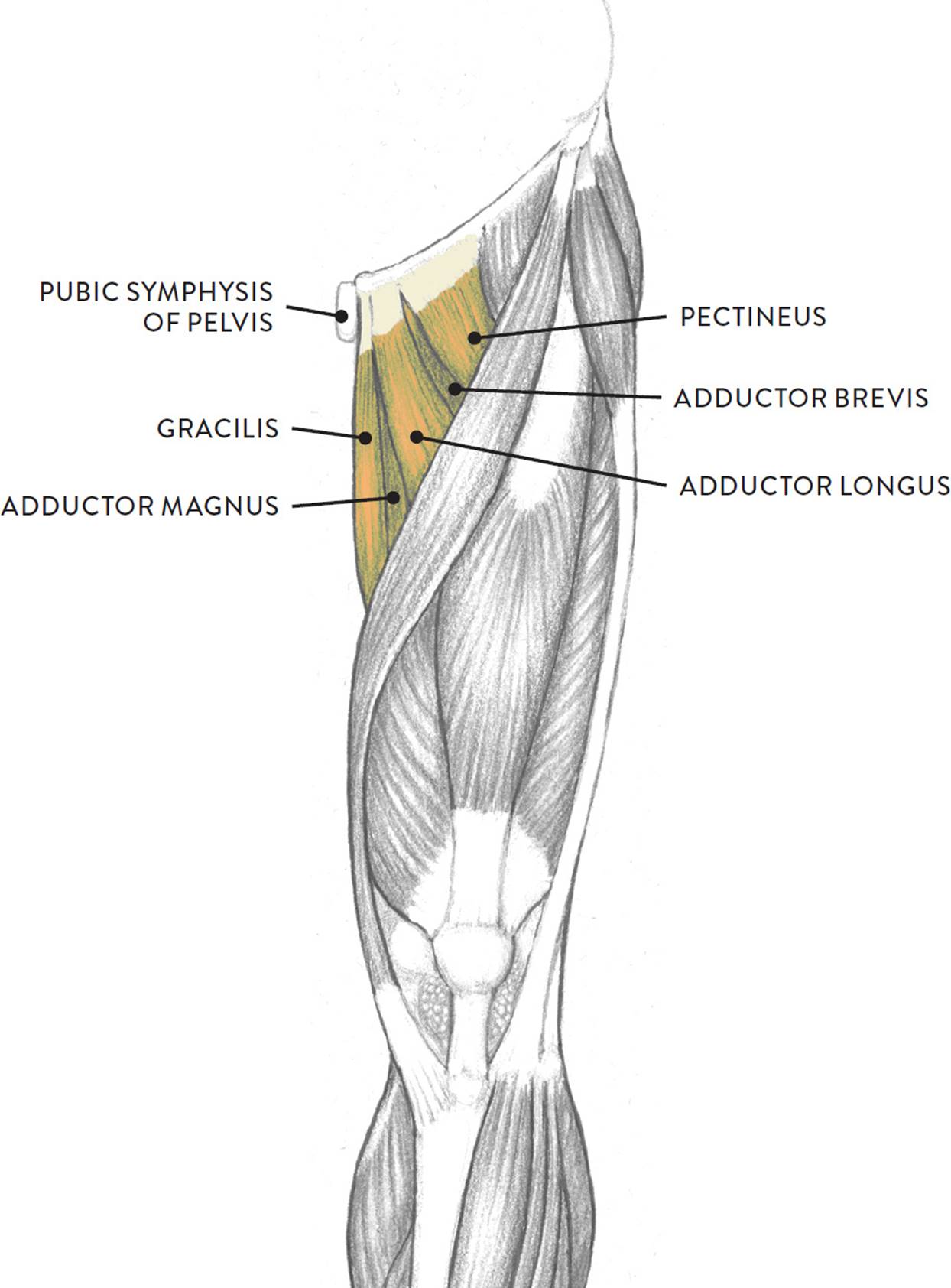

The Adductor Muscle Group

Located on the medial (inner) portion of the upper leg is a group of muscles called the adductor group, commonly known as the inner thigh muscles. The individual muscles of the adductor group are the adductor magnus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, pectineus, and gracilis, all shown in the drawing below. They contribute to the cylindrical shape of the upper leg and are not usually visible as separate muscles on the surface form.

|

Adductor Group Muscles Pronunciation Guide |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

adductor brevis |

ah-DUCK-tor BREH-viss |

|

adductor longus |

ah-DUCK-tor LON-gus |

|

adductor magnus |

ah-DUCK-tor MAG-nuss |

|

gracilis |

GRAH-suh-liss |

|

pectineus |

peck-TIN-ee-us |

ADDUCTOR MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, anterior view

The individual muscles of the adductor group begin at various locations on the lower pelvis, including the ischium bone, the pubic bone, and the vicinity of the pubic symphysis. They insert along the whole back of the femur, while the gracilis muscle moves past the knee joint to attach into the tibia. As their name indicates, they mainly perform the action of moving an outstretched leg positioned sideways from the torso back to a normal standing position (adduction). Most of these muscles also help in bending the upper leg at the hip joint (flexion).

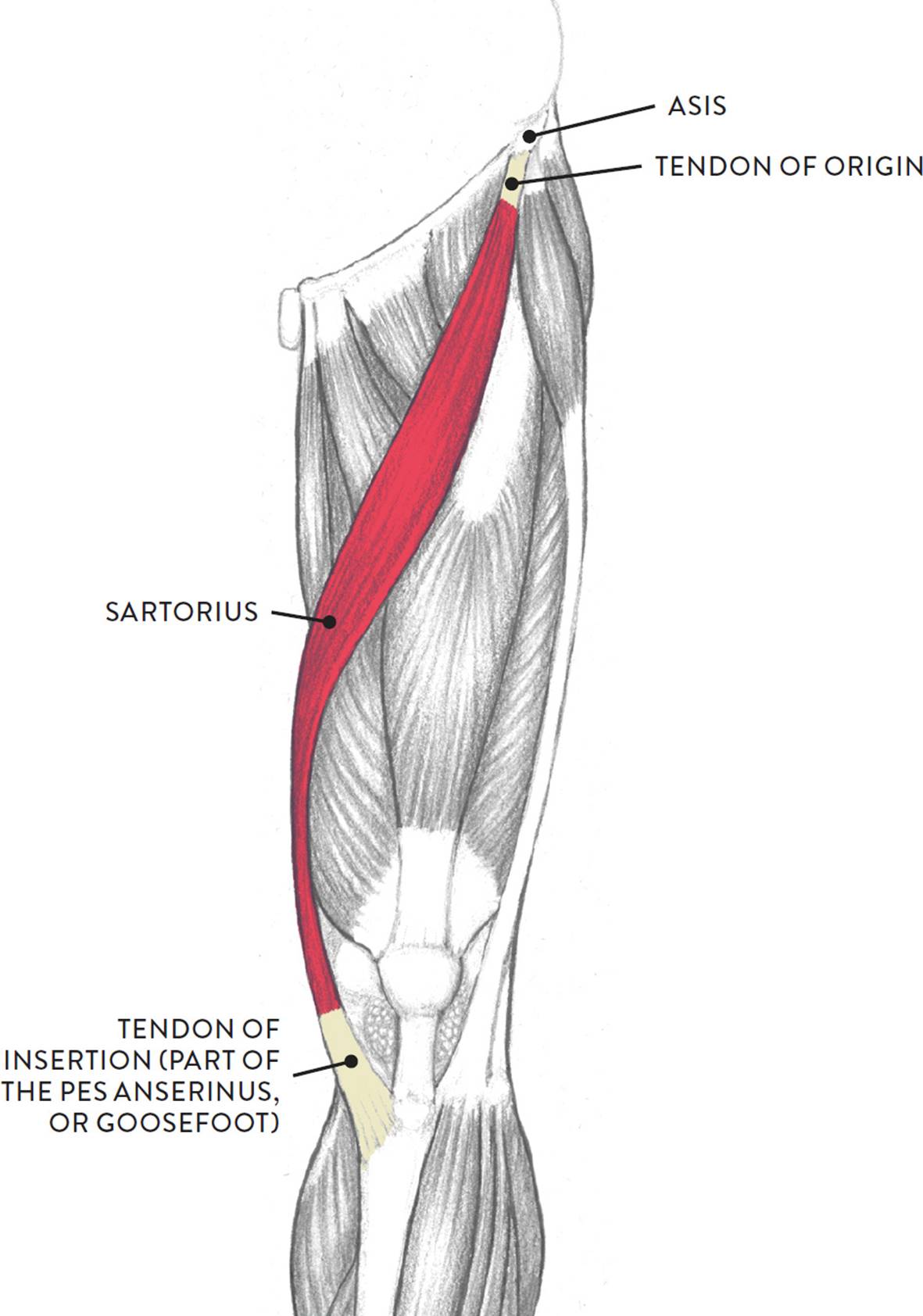

The Sartorius Muscle

The sartorius (pron., sar-TOR-ee-us), shown in the following drawing, is an elongated, straplike muscle positioned between the quadriceps and adductor muscle groups. It does not belong to any group of muscles. On athletic legs, both sides of the sartorius can usually be seen, while on average legs only the inner border of the sartorius is detectible, appearing as an elongated subtle indentation traveling diagonally on the thigh. When drawing this region, the indentation can be indicated with a soft tone or shadow.

The sartorius begins at the ASIS of the pelvis; its lower portion wraps snuggly around the inner condyles of both the femur and tibia and inserts into the medial condyle of the tibia. The tendon of the sartorius, along with other tendons, forms what is called the pes anserinus, meaning “goosefoot” because of its webbed appearance, resembling the foot of a goose. The serpentine rhythm of the sartorius, as it sweeps obliquely downward across the upper leg, is continued on the lower leg by the tibia, or shinbone, and this serpentine movement of both muscle and bone has been utilized by many figurative classical artists, past and present.

SARTORIUS

Left leg, anterior view

Contributing to many actions of the upper and lower leg, the sartorius helps move the upper leg in a forward direction from the hip joint (flexion), moves the upper leg in a side direction away from the midline of the body (abduction), rotates the upper leg in an outward direction (lateral flexion), and bends the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the knee).

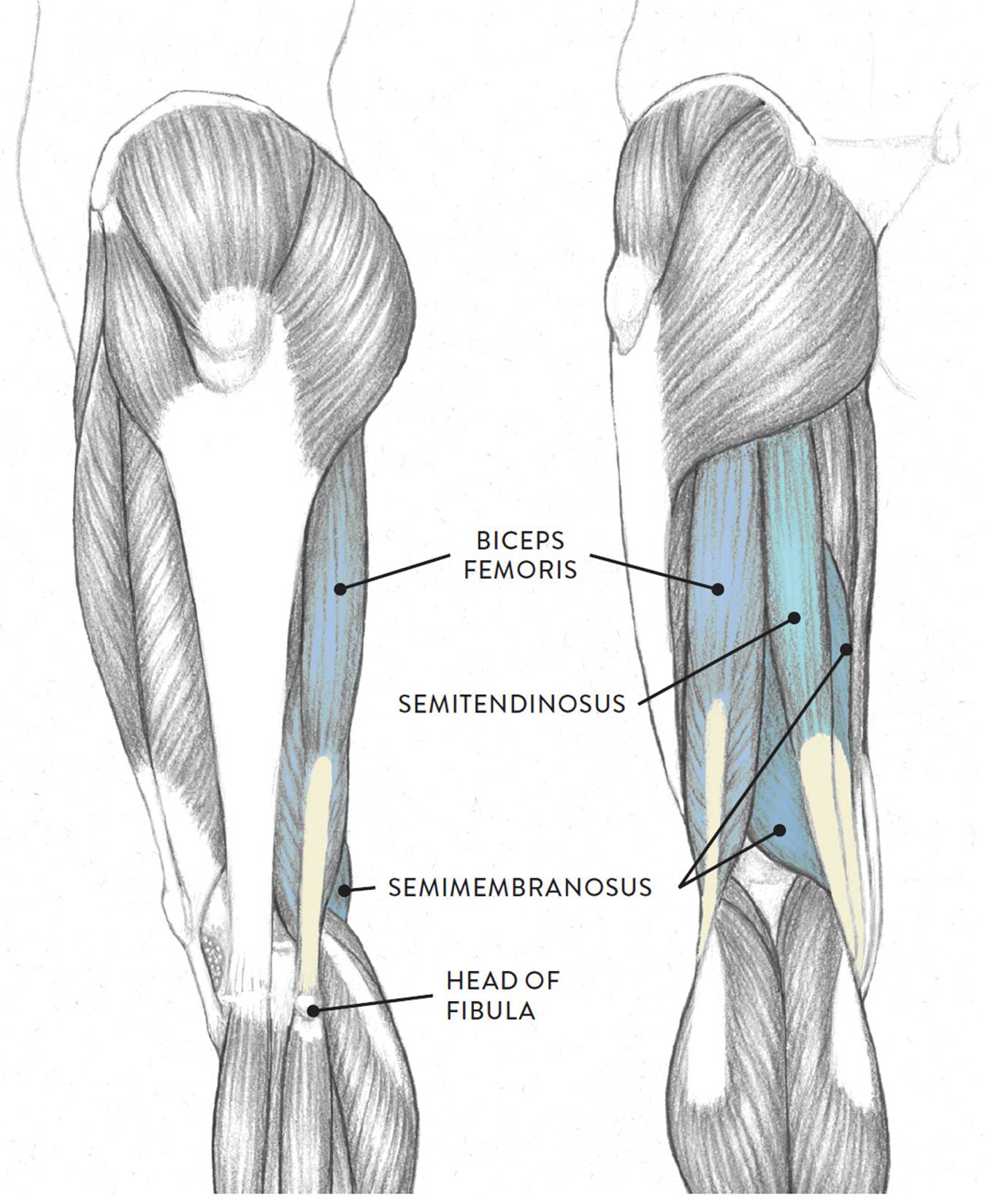

The Hamstring Muscle Group

The hamstring muscle group, shown in the next drawing, consists of three muscles—the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus—that occupy most of the posterior region of the upper leg. Usually, the hamstring group appears on the surface as a cylindrical shape, with little evidence of the individual muscles. Only on athletic legs can you see a slight furrow between the biceps femoris and the semitendinosus. The tendons of the hamstring muscles, however, do appear as “tongs” grasping the upper portions of the gastrocnemius (calf) muscle. Between the tendons is a space called the popliteal fossa, with a small fat pad. The hamstring muscles are flexors, moving the upper leg (femur) at the hip joint and the lower leg (tibia and fibula) at the knee joint.

HAMSTRING MUSCLE GROUP

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

The following life study Male Figure in a Lunging Pose, shows a figure bending one leg while the other is outstretched. The accompanying muscle diagram further reveals where the muscles are positioned in this pose.

MALE FIGURE IN A LUNGING POSE

Graphite pencil, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The biceps femoris (pron., BI-seps FEM-or-iss) is positioned on the posterior and lateral portions of the upper leg. As its name implies, it has two heads (a long head and a short head), which usually appear as a single large form on the outer posterior region of the upper leg. The long head begins on the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis and the short head begins at the back of the femur. The powerful tendon of the biceps femoris, which produces a thick, cordlike form on the surface, inserts into the small, spherical head of the fibula. The biceps femoris bends the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of lower leg), rotates the lower leg in an outward direction when the knee is bent (lateral rotation of lower leg), and straightens the upper leg at the hip joint (extension).

The semitendinosus (pron., SEM-ee-TEN-dih-NO-sus or seh-MY-ten-din-OH-sus) is positioned on the posterior and medial portions of the upper leg. The muscle begins on the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis. Its tendon and the tendon of the semimembranosus are side by side and attach on the medial side of the tibia bone. The semitendinosus helps bend the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the lower leg), rotates the lower leg in an inwardly direction (medial rotation, but only when the knee is bent), and helps straighten the upper leg at the hip joint (extension).

The semimembranosus (pron., SEM-ee-mem-brah-NO-sus or seh-MY-mem-bran-OH-sus) is mostly covered by the semitendinosus and is hard to detect on the surface of an average leg, although occasionally a small bulge will appear near the back of the knee region. The muscle begins on the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis and inserts on the posterior surface of the inner condyle of the tibia. The semimembranosus helps bend the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the lower leg) and rotates the lower leg in an inward direction (medial rotation, but only when the knee is bent). It also helps straighten the upper leg at the hip joint (extension).

Three Muscle Groups of the Lower Leg

Muscles of the lower leg move the lower leg at the knee joint and the foot at the ankle joint. There are three main muscle groups. The most prominent is the flexor muscle group of the lower leg, commonly known as the calf muscles,located on the posterior region of the lower leg. Situated on the anterior portion of the lower leg is the extensor muscle group of the lower leg, and occupying the lateral (outer) region of the lower leg is the peroneal muscle group.

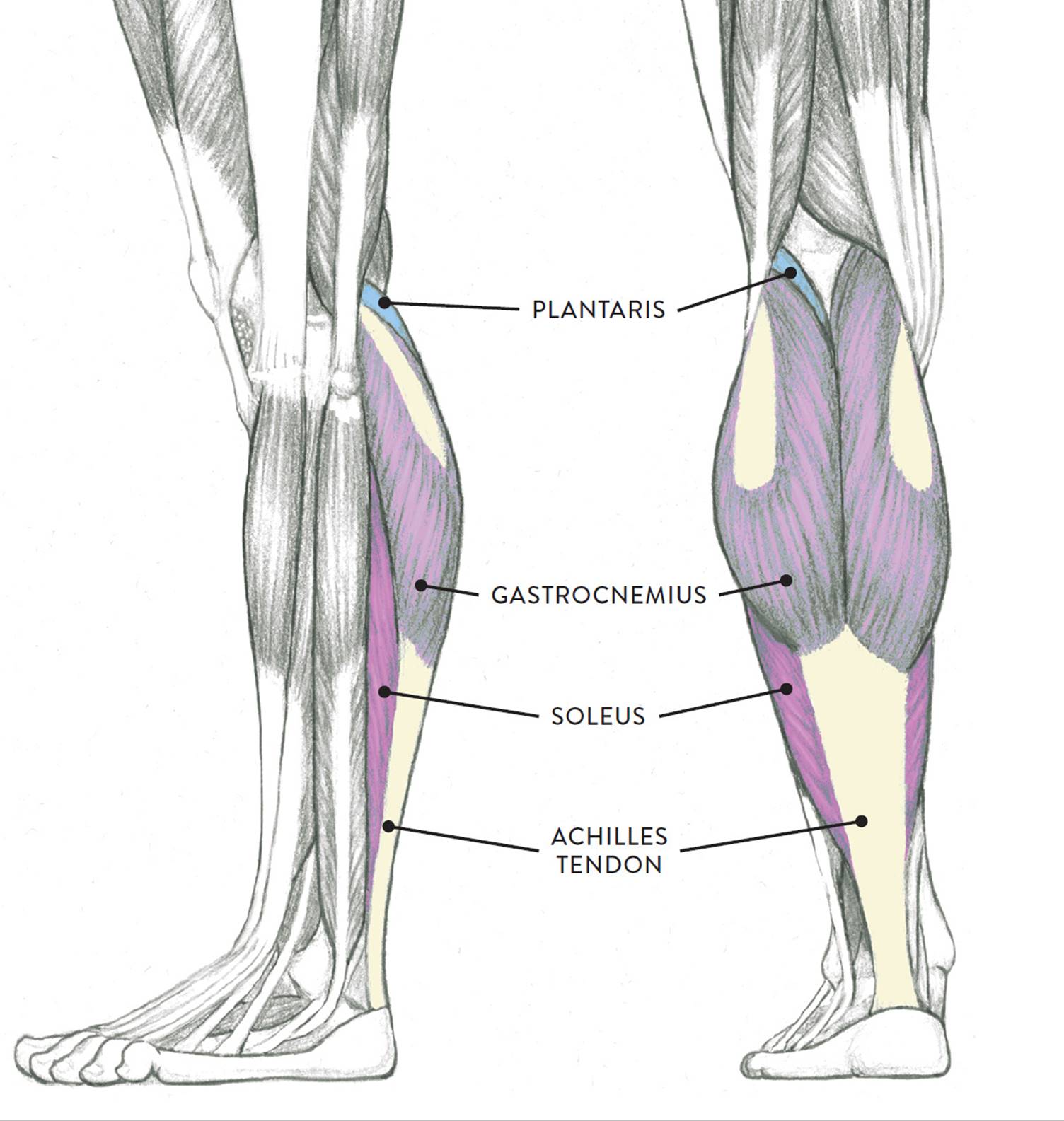

The Flexor Muscle Group of the Lower Leg

The flexor group occupies the posterior region of the lower leg, as shown in the next drawing. The group consists of the two-headed gastrocnemius muscle, the soleus muscle, and a smaller muscle called the plantaris. An older term—triceps surae (pron., TRI-seps SHUR-ay), which means “the three-headed muscle of the calf”—refers to both the gastrocnemius (with its two heads) and the soleus but not the plantaris muscle. The flexor group muscles move the lower leg (tibia) at the knee joint and the foot at the ankle joint.

FLEXOR MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER LEG

Left leg, lateral (left) and posterior (right) views

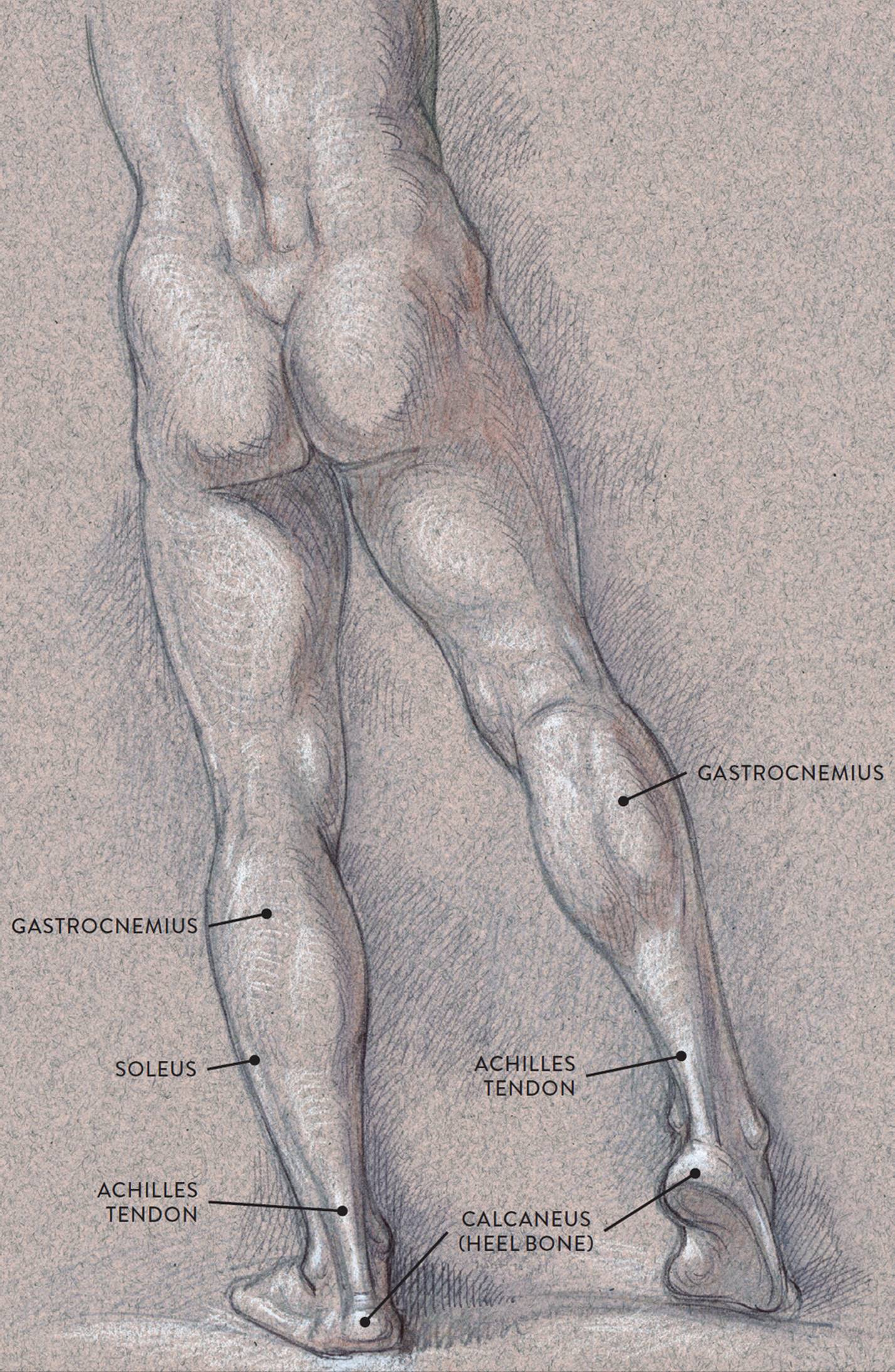

In the following life study Male Figure with Right Leg Positioned on the Ball of the Foot, you can see the rich bulging shape of the gastrocnemius muscle with its tendon (the Achilles tendon) appearing as a thick cord as it inserts into the heel. The accompanying muscle diagram shows the locations of the various surrounding muscles.

MALE FIGURE WITH RIGHT LEG POSITIONED ON THE BALL OF THE FOOT

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, watercolor wash, and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The gastrocnemius (pron., gas-trock-NEE-mee-us), more commonly known as the calf muscle, is an impressive oval muscular shape occupying the upper half of the lower leg in the posterior region. The two heads of the gastrocnemius begin on the large condyles of the femur—the lateral head on the lateral condyle and the medial head on the medial condyle. The muscle fibers merge into a common tendon, which inserts into the calcaneus of the foot (heel bone). Its tendon appears as a neutral area until it converges into the thick cordlike form known as the Achilles tendon. The tendon serves as an important landmark for artists as it flows downward from the rich shape of the calf to eventually anchor into the heel bone. The gastrocnemius helps bend the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion of the lower leg). When it contracts it also helps raise the heel, which is seen in the action of pointing the foot (plantar flexion) and in the tiptoe position.

The soleus (pron., SO-lee-us or SOL-ee-us) is positioned beneath the gastrocnemius; only its outer and inner borders appear on the surface, as elongated muscular ridges. The soleus shares the same broad tendon with the gastrocnemius. The muscle begins on the fibula, near the head and upper surface of the shaft, as well as on the tibia and the interosseous membrane. It inserts into the calcaneus (heel bone) by way of the Achilles tendon. The soleus helps raise the heel in walking, in standing on tiptoe, and in the action of pointing the foot downward (plantar flexion).

The plantaris (pron., plan-TARE-iss) is a small, somewhat flattened fusiform muscle with an extremely long, slender tendon. It is mostly covered by the lateral head of the gastrocnemius, with only a small portion being exposed near the popliteal fossa. Its presence is noticeable only on muscularly well-defined legs. The muscle begins on the lower part of the femur near the lateral epicondyle. Its tendon attaches into the calcaneus (heel bone). The plantaris’s action is very weak, but it assists in bending the lower leg at the knee joint (flexion) and helps in raising the heel up, which is seen as the action of pointing the foot downward (plantar flexion).

The Extensor Muscle Group of the Lower Leg

Positioned on the front portion of the lower leg, the muscles of the extensor group are the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor hallucis longus, as shown in the following drawing. The peroneus tertius also belongs to the extensor group, although its name might lead you to think that it is part of the peroneal group (see this page). The extensor group muscles help move the foot at the ankle joint and extend the toes.

EXTENSOR MUSCLE GROUP OF LOWER LEG

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

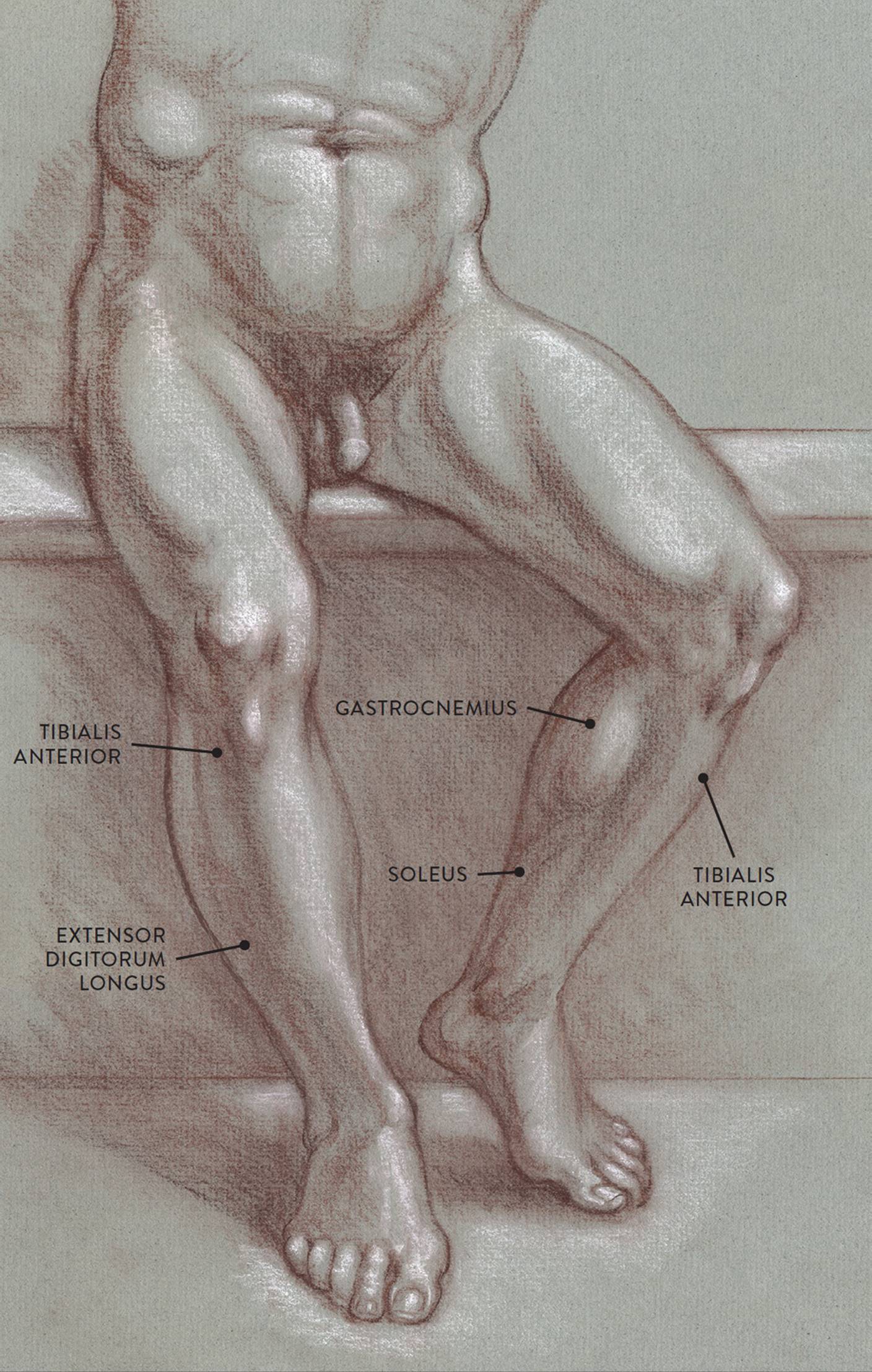

The following life study Lower Torso and Legs in a Frontal View, shows the lower torso of a male figure. The accompanying muscle diagram reveals the position of the muscles of the lower legs in this pose.

LOWER TORSO AND LEGS IN A FRONTAL VIEW

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils, with white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLE DIAGRAM

The tibialis anterior (pron., tib-ee-AL-iss an-TEER-ee-or), also known as the shin muscle, is an elongated fusiform muscle that travels down the leg obliquely. Its cordlike tendon is noticeable near the inner ankle joint when the foot is lifted upward. The muscle begins on the tibia and the interosseous membrane. The elongated tendon of the tibialis anterior inserts on the side of the foot on the medial cuneiform tarsal bone and the base of the first metatarsal. The muscle raises the foot upward at the ankle joint (dorsiflexion) and turns the foot in an inward direction (inversion).

The extensor digitorum longus (pron., ek-STEN-sor dij-ih-TOR-um LON-gus) is a slender muscle positioned next to the tibialis anterior on the front of the lower leg. This muscle can appear as an elongated ridge on muscular individuals; on most people, however, it blends with the tibialis anterior. The extensor digitorum longus begins on the tibia and fibula and the interosseous membrane. About halfway down the lower leg the muscle fibers merge into a broad flat tendon, which then splits near the ankle joint into four individual tendons, each inserting into one of the four lesser toes. These tendons are detected on the surface when the toes are spread outward. The extensor digitorum longus raises the foot upward at the ankle joint (dorsiflexion) and also lifts the lesser toes upward (extension).

The extensor hallucis longus (pron., ek-STEN-sor HAL-loo-sis LON-gus or ek-STEN-sor HALL-luc-kiss LON-gus), commonly called the great toe muscle, is positioned beneath and between the tibialis anterior and the extensor digitorum longus. The great toe muscle begins on the fibula and the interosseous membrane. Its muscle fibers are usually not seen on the surface, but its cordlike elongated tendon is visible as it inserts into the large toe, especially when the muscle contracts, lifting the toe. (Many artists mistake this tendon for the tendon of the tibialis anterior, but the tibialis anterior’s tendon, although positioned near the great toe’s tendon at the ankle region, veers off to attach into the inner side of the foot.) The extensor hallucis longus raises the toe (extension of great toe) and also assists in lifting the foot upward (dorsiflexion).

The peroneus tertius (pron., pair-oh-NEE-us TER-shee-us), also known by the older name fibularis tertius, is anatomically part of the extensor muscle group, not the peroneal muscle group. The peroneus tertius begins on the front portion of the fibula and the lower part of the interosseous membrane and inserts into the fifth metatarsal of the foot. Like the peroneus muscles, it helps turn the foot in an outward direction (eversion). And like the extensor muscle group, it helps raise the foot upward from the ankle joint (dorsiflexion).

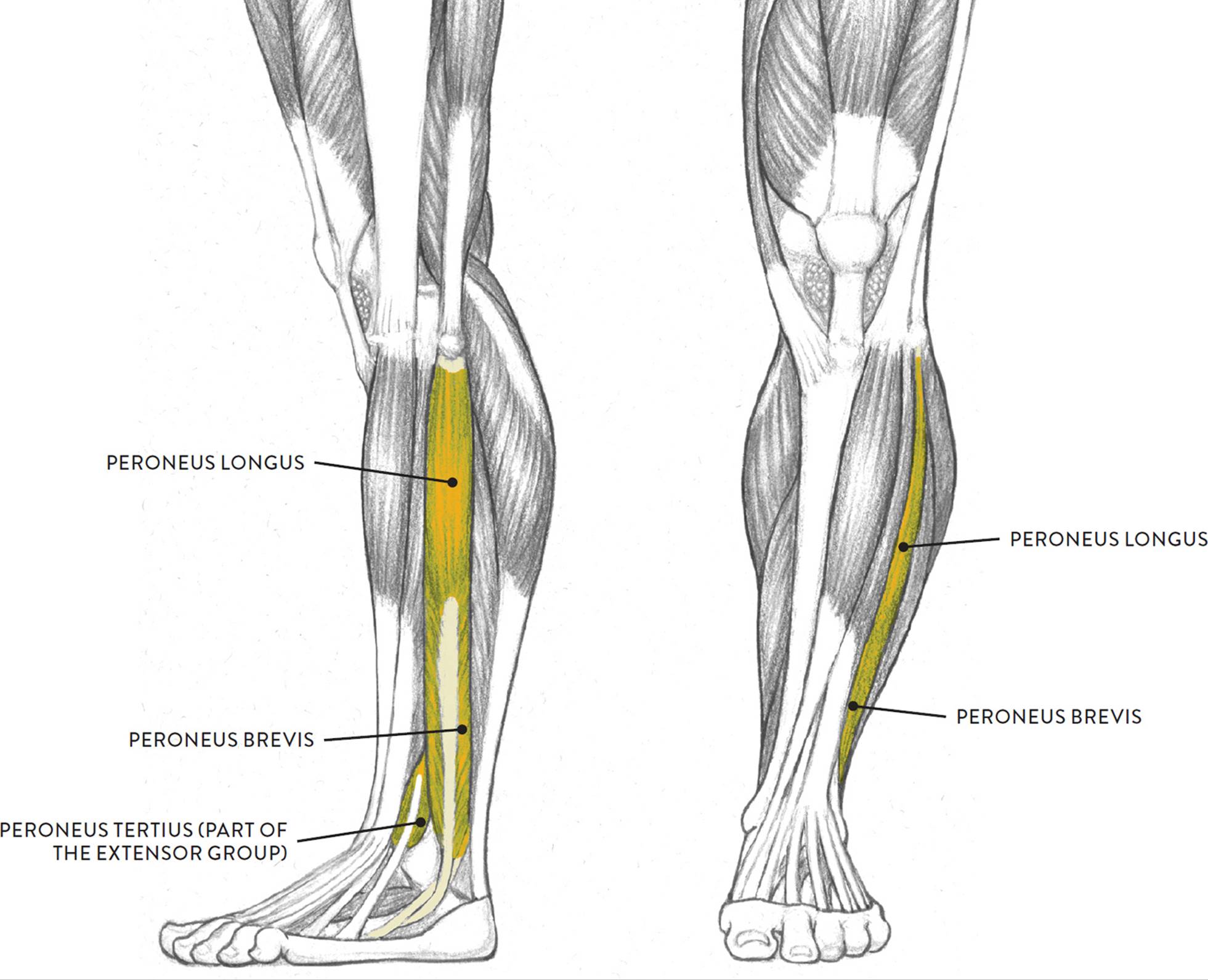

The Peroneal Muscle Group of the Lower Leg

The peroneal group consists of two muscles located on the lateral side of the lower leg: the peroneus longus and the peroneus brevis. Shaped like an elongated bootstrap, the peroneal muscles move the foot at the ankle joint and help stabilize the ankle. They appear as elongated muscular ridges that are more apparent on joggers, bicyclists, and others who use their lower leg muscles extensively.

PERONEAL MUSCLE GROUP OF THE LOWER LEG

Left leg, lateral (left) and anterior (right) views

The peroneus longus (pron., pair-oh-NEE-us LON-gus or pair-RONE-ee-us LON-gus) is the larger of the two peroneal muscles. It is a bipennate muscle with a long, slender tendon, which can be seen riding close to the edge of the fibula, where it wraps around the outer ankle before inserting into the foot. It begins on the head of the fibula and the lateral condyle of the tibia and inserts into the foot at the base of the first metatarsal and the medial cuneiform tarsal bone. The peroneus longus helps point the foot from the ankle joint (plantar flexion) and helps turn the foot outward (eversion).

The peroneus brevis (pron., pair-oh-NEE-us BREV-iss or pair-RONE-ee-us BREH-viss) is also a bipennate muscle. It begins on the lower two-thirds of the fibula and inserts into the base of the fifth metatarsal of the foot. Like its larger partner, it helps point the foot (plantar flexion) and helps turn the foot outward (eversion).

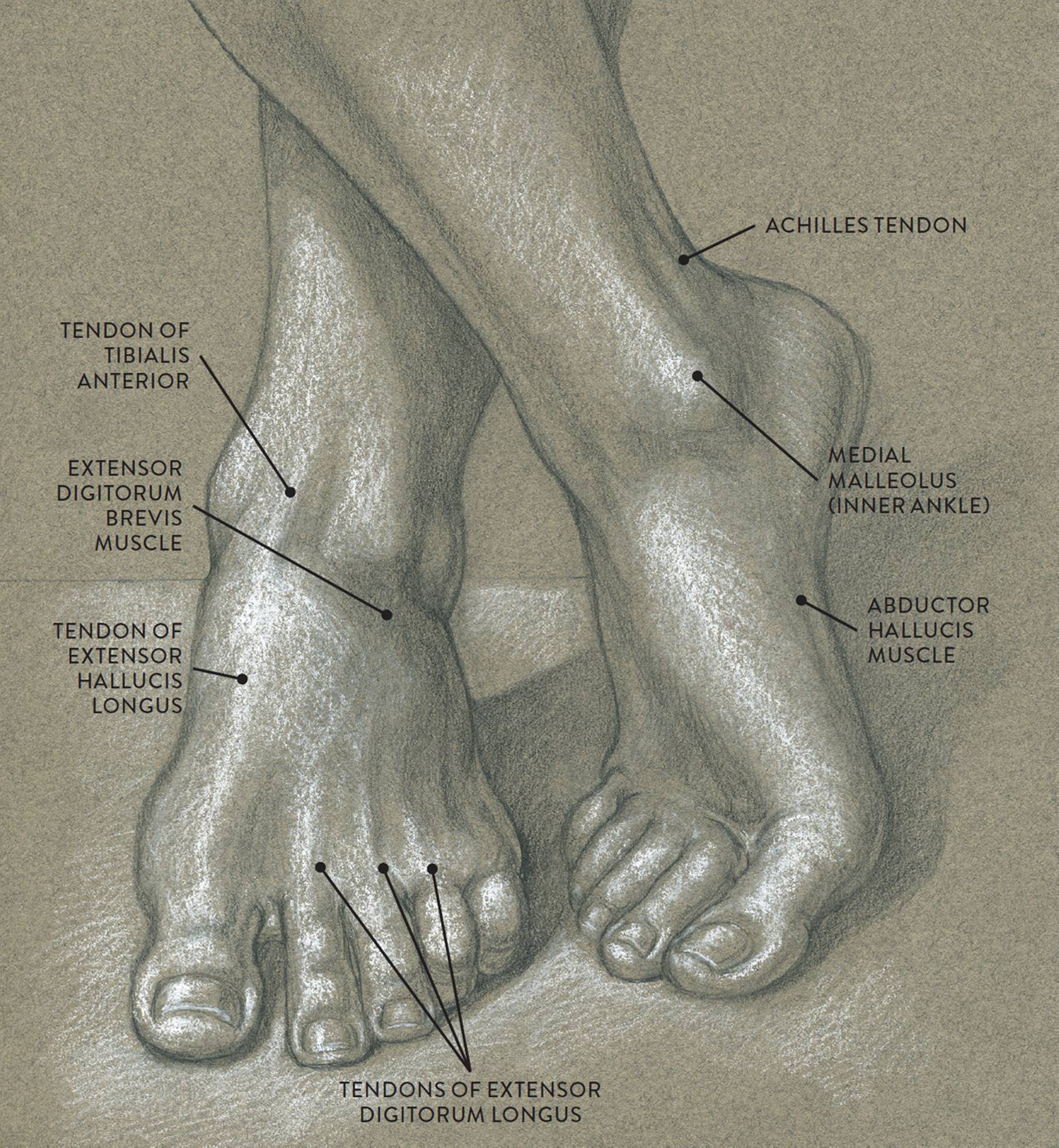

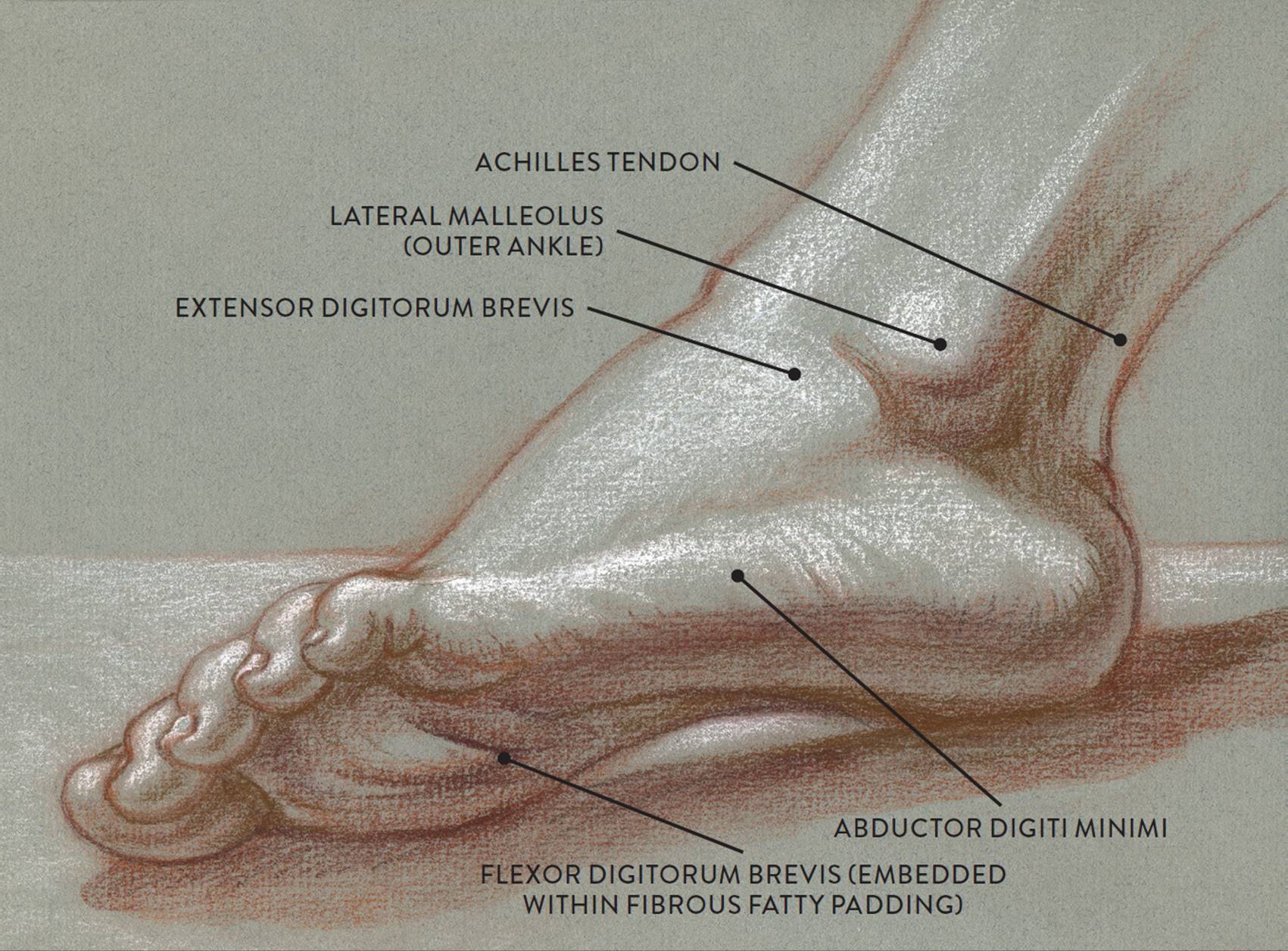

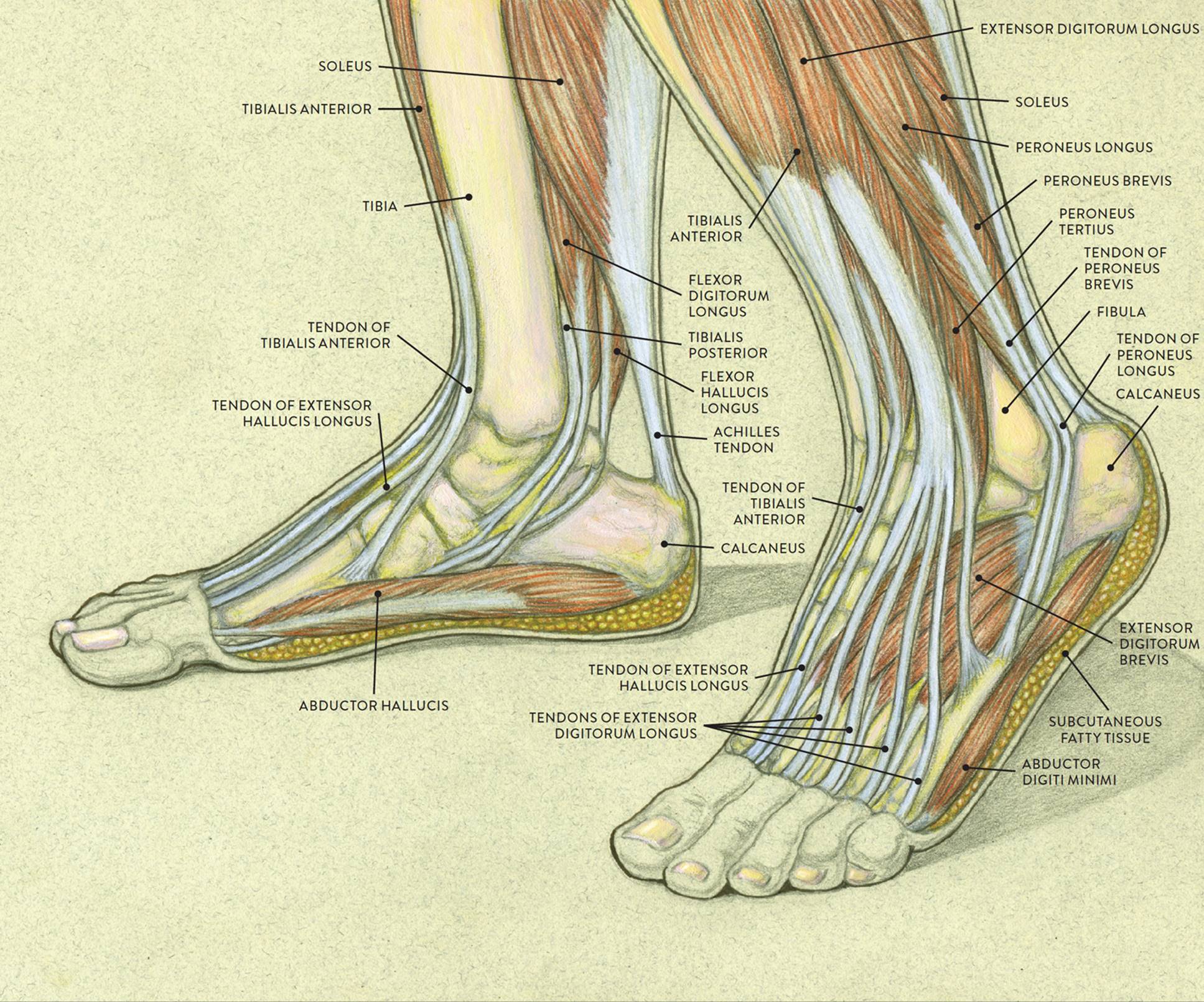

Muscles of the Foot

The foot is a fascinating structure, composed of many bones, ligaments, and cartilages; a few muscles; layers of tendons; and a large amount of fatty tissue that provides shock absorption. The drawing on this page shows the complexity of the foot’s internal structures.

The dorsal (top) part of the foot contains the tendons descending from the muscles of the lower leg, each one continuing into a different toe. These tendons can at times be seen quite clearly, especially when the toes are spread apart (adduction of the toes). The only muscle located on the dorsal region of the foot is the extensor digitorum brevis, which appears as a small, soft, egglike form near the outer ankle bone (lateral mallelous of the fibula). It helps straighten the lesser toes (extension) and is activated in walking and running when the toes are pulled upward to clear the ground.

|

Muscles of the Foot Pronunciation Guide |

|

|

MUSCLE |

PRONUNCIATION |

|

abductor digiti minimi |

ab-DUCK-tor DIH-jih-tee MIN-ih-mee |

|

extensor digitorum brevis |

ek-STEN-sor dij-ih-TOR-um BREV-iss |

|

abductor hallucis |

ab-DUCK-tor HAL-loo-siss |

Along the outer edge of the foot, beginning near the fifth toe and terminating in the heel region, is the abductor digiti minimi. This narrow, streamlined muscle is padded with fatty tissue on its lower border and appears as a noticeable ledge along the outer region of the foot. When this muscle contracts, it pulls the little toe sideways from the foot (abduction) and also helps bend the little toe (flexion).

Another elongated muscle, the abductor hallucis, is attached along the inner arch of the foot and can be seen occasionally. When this muscle contracts it pulls the large toe sideways from the foot (abduction).

As with the hands, I recommend practicing drawing the feet in many different positions. Sketching the feet from various sources (master artists’ paintings and sculpture, models’ feet, photos) will help you gain confidence and skill when approaching these difficult forms. The studies can be gesture drawings (see this page) that quickly capture the general shape of the foot or longer studies, such as the ones to the right, that emphasize the anatomical forms of the foot.

STUDY OF FEET

Graphite pencil and white chalk on toned paper.

STUDY OF A LEFT FOOT IN A LATERAL VIEW

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils and white chalk on toned paper.

MUSCLES AND TENDONS OF THE FOOT

LEFT: Medial (inner side) view of right foot

RIGHT: Lateral (outer side) view of left foot

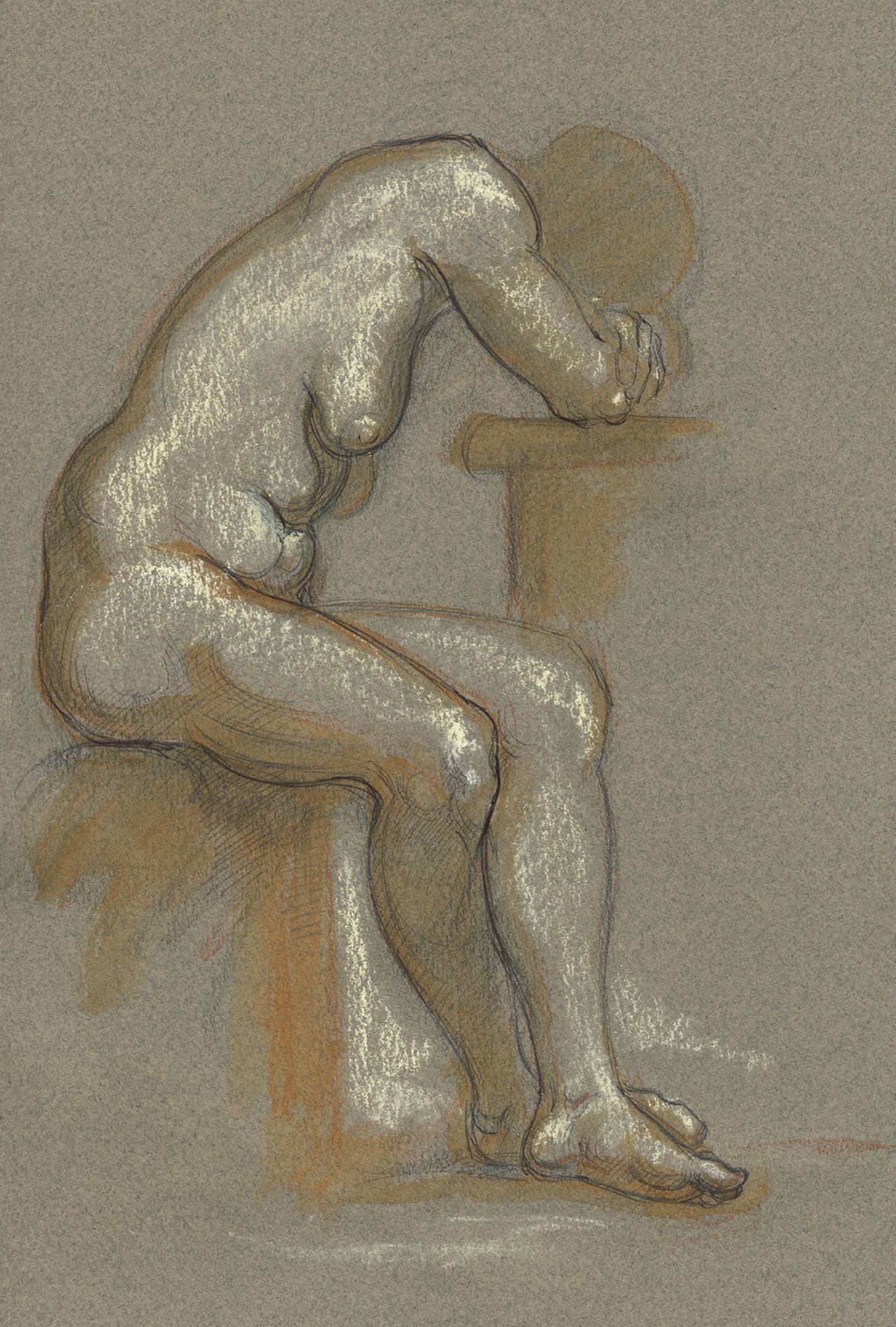

STUDY OF FEMALE FIGURE SITTING, SIDE VIEW

Graphite pencil, ballpoint pen, watercolor pencil, and white chalk on toned paper.