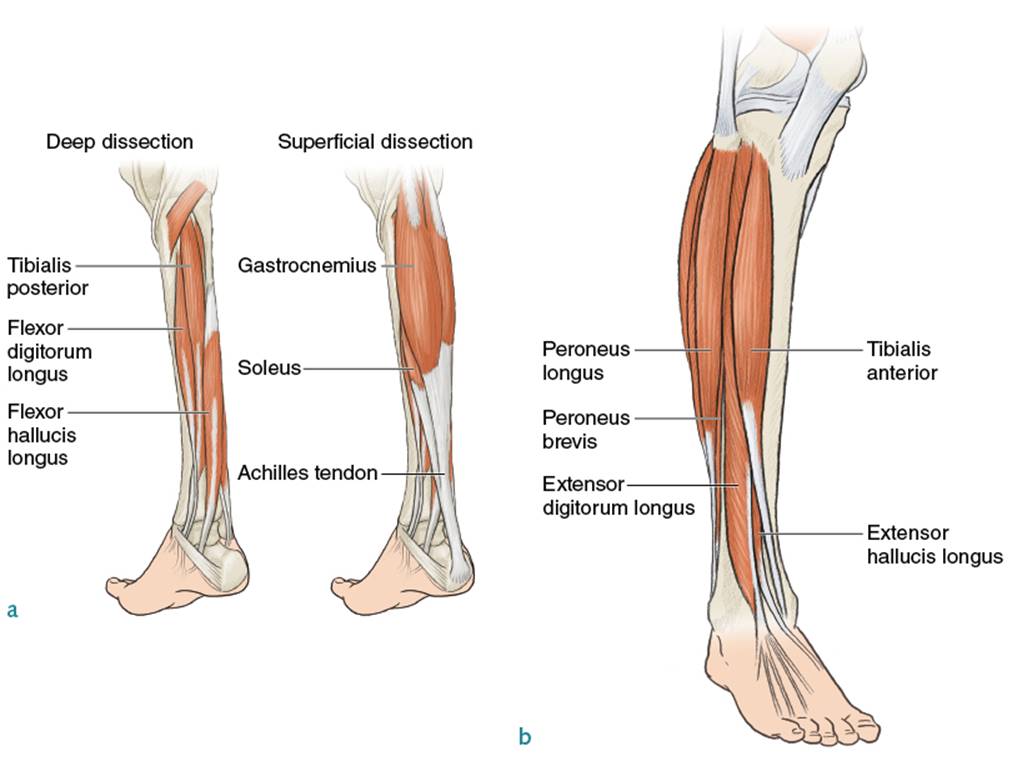

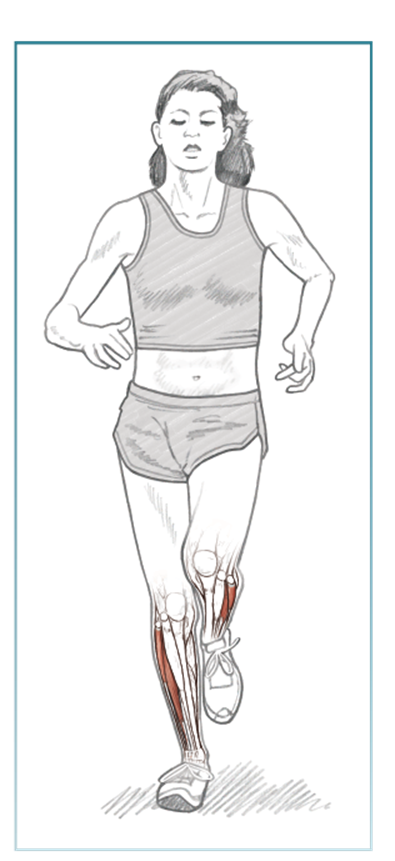

Any structure that will pass the test of longevity must have a strong, secure, and preferably wide base. The human being is certainly not a pyramid, which is the perfect example of such a design, yet to remain upright the human has to survive with two stable lower limbs, augmented by relatively large feet, over a fairly narrow base.

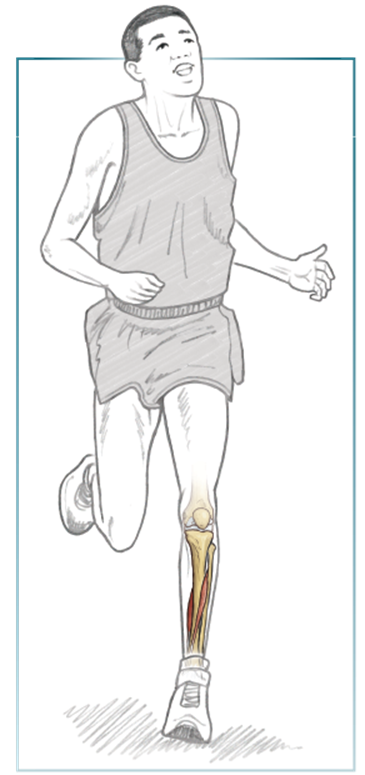

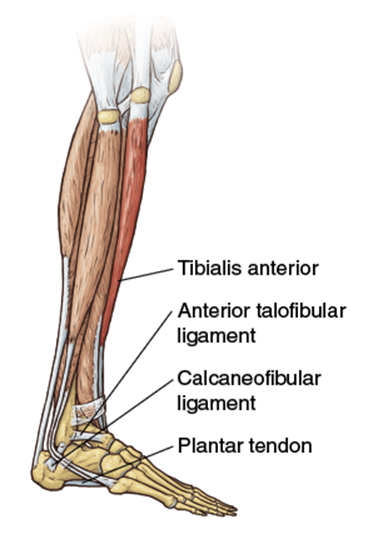

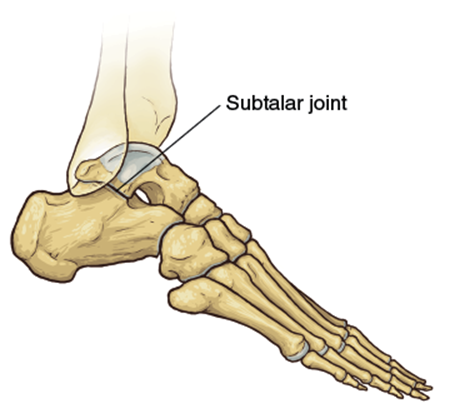

The tibia (figure 9.1) is the major weight-bearing bone of the lower leg. It is splinted by the thinner fibula, which becomes more relevant at the ankle, where it forms the outer part of this hinged and curved joint. The muscles attached to these bones control the movement of both the ankle and the metatarsals and phalanges that form the foot. The ankle joint itself moves almost entirely in the anterior-to-posterior plane, but the seven bones that form the tarsus are placed so that there can be both inversion and eversion of the foot at the midtarsal and subtalar joints. This allows each foot to turn inward and outward to accommodate for uneven or slippery ground underfoot.

Figure 9.1 Bony structures and soft tissues of the lower leg and foot.

Only three bones on the undersurface of the foot make contact with the ground. Under the heel is the calcaneum, and the first and fifth metatarsal heads complete the triangle. Between this tripod of bones is a complex consisting of the talus, cuboid, navicular, and three cuneiform bones, which lie in opposition to each other in such a way that they can be raised to form a longitudinal, or lengthwise, arch to each foot with the five metatarsal bones. Not only do they have to change position to compensate for variations underfoot, but they also allow the feet sideways movement. The tarsal bones form the apex of a bony arch, and when viewed from the ends of the toes appear to rotate on each other to enable the feet to move in or out. It is by this movement that walking or running on the inside or outside of the feet is possible.

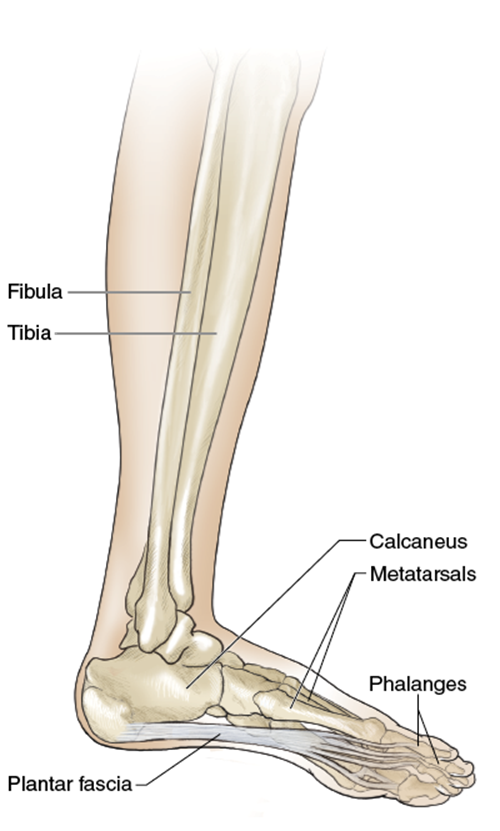

The power from the calves to push forward comes from the two muscles of the posterior compartment (figure 9.2). The soleus is the deeper muscle and combines with the gastrocnemius to form the Achilles tendon, which is inserted into the calcaneum. Their contraction pulls this bone and thus the whole foot backward. A deeper layer of muscles provides flexion to the metatarsals and toes. These are the flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus, and tibialis posterior. They provide plantarflexion to the foot and, because they cross several joints, to the ankle as well.

Figure 9.2 Lower leg and foot: (a) back and (b) front.

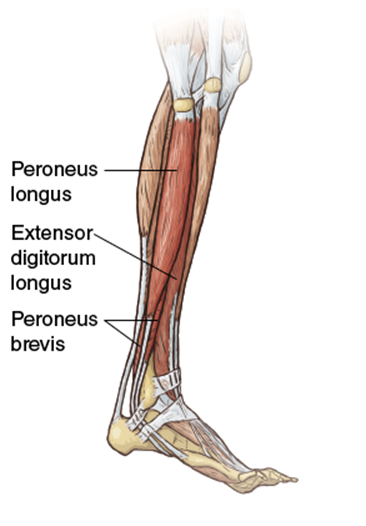

The anterior, or extensor, compartment of the leg lies between the tibia and fibula and is surrounded by a relatively inelastic fibrous sheath. Within it are contained the tibialis anterior, extensor digitorum longus, and extensor hallucis longus muscles. These pass through the front of the ankle and are inserted into the tarsal, metatarsal, and toe bones in order to raise them or lift them up, an action known as dorsiflexion. These do not have to generate the same power as the posterior calf muscles for most activities, so they are less developed and weaker. Further lateral stability to the ankle and rear foot is provided by the peroneal muscles, which arise from the fibula and pass around the lateral side of the ankle joint to be inserted into the outer metatarsals.

Very powerful forces are generated through the Achilles tendon. If it is injured, it tends to be very painful because of its well-developed nerve supply and heals slowly because of poor blood flow. Much the same can be said of the plantar tendon, or fascia, which spreads from the front of the calcaneum and is inserted at the bases of the five metatarsals. It is an unyielding sheet of fibrous tissue whose weakest point is at the heel. If the foot is viewed two-dimensionally from the inside, the plantar tendon provides the horizontal base to the triangle completed by the tarsal and metatarsal bones.

This anatomy must be considered on a functional basis, and watching a slow-motion recording of a foot landing and taking off is invaluable in understanding the motion involved in each stride. The initial plant of the foot is known as the heel strike, after which the foot turns a little inward, with the weight of the body progressively passing down the outer side of the foot before landing is completed on the ball formed by the metatarsal bases. Fewer runners meet the ground first with their toes, sometimes because of an inability to dorsiflex sufficiently. This lack of heel strike may be due to genetic or structural causes. Most people can run on their toes only for a very short time and distance because the work of plantarflexion is taken over by the comparatively weak toe flexors rather than the powerful calf muscles working through the pivot of the calcaneum, especially if dorsiflexion is limited.

Once the foot is flat, the movement continues in reverse; during takeoff, the heel lifts off first, rolls inward along the outer metatarsals, and ends with the final push-off from the ball of the foot. During this action, all the muscles will contract or expand in a regular rhythm, though not at the same time.

At this juncture we need to demystify the superstitions that have developed around feet that are pronated or supinated. There are three related but separate elements to movement within the foot. At the subtalar joint, the foot inverts and everts, or turns inwardly or outwardly. At the midfoot, there is abduction or adduction, where the movement is solely in the horizontal plane, while at the forefoot, the movement is principally up and down, in dorsiflexion, which somewhat confusingly describes an extension of the foot, or plantarflexion. Pronation describes a compound movement of these joints, where there is eversion at the subtalar joint, abduction (i.e., outward horizontal movement) at the midfoot, and dorsiflexion at the forefoot. Supination describes the opposite movement of each joint. Every foot, with every stride, exhibits some of these actions. When they become excessive, the runner may have difficulties that lead to pain or injury. Excessive pronation when the foot is flat on the ground, where the longitudinal arch of the foot leans excessively inward and the toes point outward, will stress the tibia by internally rotating it and the ligaments between the bones of the midfoot by stretching them, affecting the ability of the inverting muscles of the feet to perform efficiently. Supination describes the opposite action, in which the outside of the runner’s foot takes the weight of landing on the ground. The tibia is disproportionately externally rotated, and the effect of the extra strain on the peroneal muscles may also spread to the iliotibial band. (In chapter 11 we demonstrate how appropriate footwear may minimize the distress that overpronation and supination may pose to the serious runner.) Because of the strains imposed when the feet are excessively overmobile, a severely supinated foot may prove too much of a handicap for a distance runner, though many of the fastest runners in the world have overcome this potential disability.

Another anatomical variation concerns those with high, rigid, longitudinal arches, who may also but not necessarily supinate, and those with flat arches with or without excessive pronation. For both of these types of feet, the lack of flexibility is likely to lead to a mechanical disadvantage in that they may be slower runners than they otherwise might.

Specific Training Guidelines

Some of the standing exercises are performed or can be performed unilaterally, meaning one leg at a time. This type of movement can significantly strengthen the targeted muscles by recruiting all the major leg muscles, weaker ones included, to establish balance while properly performing each exercise.

As mentioned in chapter 5 and thoroughly examined in chapter 7, exercises that require stability engage the core muscles of the abdomen, lower back, and hips to maintain proper form. Performing most freestanding exercises unilaterally helps ensure that the specific muscles targeted plus the core muscles recruited develop strength and, with enough reps, muscular endurance.

![]()

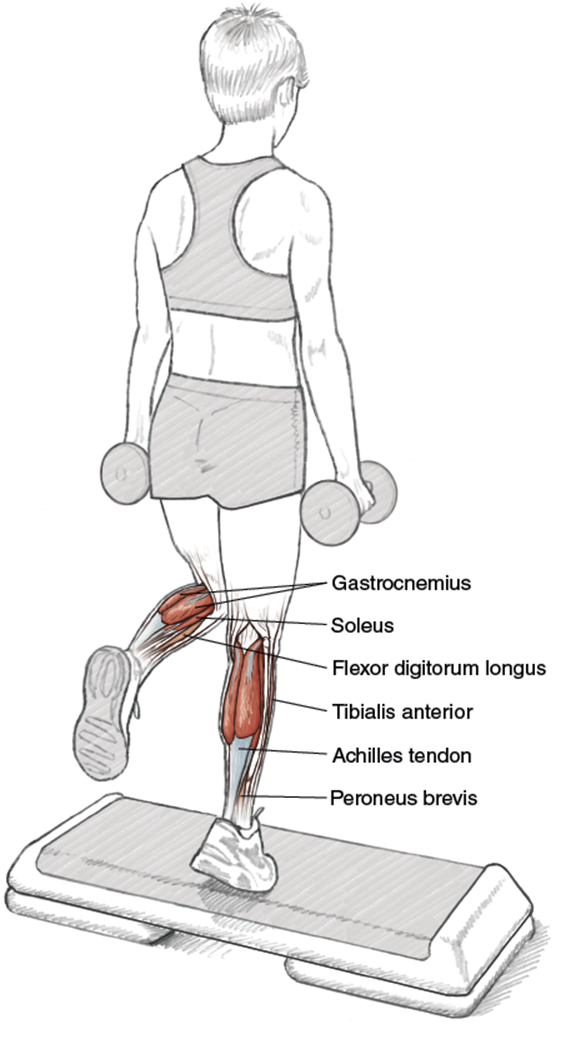

Single-Leg Heel Raise With Dumbbells

Technique Tip

•The exercise should be performed until the calf muscles begin to burn. Do not perform to fatigue unless performing only one set. One to three sets will suffice, with the amount of weight held being a variable that can change the effect of the workout.

Execution

1. Stand on a platform with one foot touching the platform with only the ball of the foot and the toes. The midfoot and the heel are not touching the platform. Hold the other leg at a 90-degree angle at the knee, from the hip, not touching the platform. Both hands should be holding dumbbells, with the arms extending straight down along the hips and sides of the quadriceps.

2. Maintaining proper posture, an erect upper body stabilized by the engagement of the abdominal muscles, rise up (plantarflexion) on the foot on the platform. Do not hyperextend the knee. The leg should be straight or slightly bent at approximately 5 degrees.

3. Lower the foot (dorsiflexion) back to the beginning position. Complete to tolerance each set and then repeat the exercise using the other leg.

Muscles Involved

Primary: gastrocnemius, soleus

Secondary: tibialis anterior, peroneus brevis, flexor digitorum longus

Soft Tissue Involved

Primary: Achilles tendon

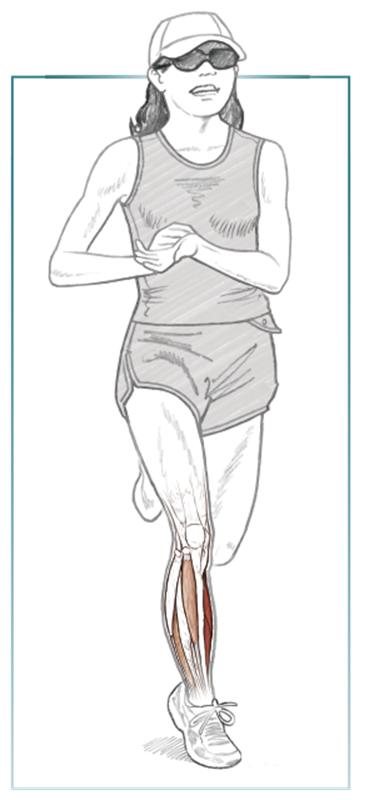

Running Focus

The single-leg heel raise exercise should be a staple of every runner’s strength-training regimen because it is a simply-performed exercise with very little equipment, and because it is a multipurpose exercise. Specifically, it can be performed to develop strength, which aids in injury prevention, and it can be used as a rehabilitation exercise if the Achilles tendon or calf muscles have been injured. The exercise should not be performed if a runner is still suffering the initial effects of the injury, but can be safely performed after the onset of the injury if some healing, determined by a subjective evaluation of the pain level or the evaluation of an objective image (MRI), has taken place.

As described in chapter 10, adding an eccentric, or negative, component of the exercise (lengthening of the muscle) adds value to this specific calf and Achilles tendon exercise. Eccentric motions have value because the muscle can handle a lot more weight eccentrically contracting. It is also hypothesized that muscle strengthening is greatest when performing eccentric-contraction movements and that eccentric contractions are better suited to develop a muscle’s fast-twitch fibers.

![]()

Machine Standing Heel Raise

T

echnique Tip

• The upper body should be erect and the abdominal muscles should be engaged to maintain proper form.

Execution

1. Stand under the shoulder pads of the machine so that there is a small amount of flex at the knees. The upper body should be erect and the abdominal muscles should be engaged to maintain proper form. Arms should be placed on the handles next to the shoulder pads. A light grip should be used.

2. Elevate the heels (plantarflexion) until both feet are only touching the platform with the metatarsals and toes; however, the toes should be relaxed and the emphasis should be on the extension of the calf muscles.

3. Lower the heels until a full stretch of the calves is felt. Repeat.

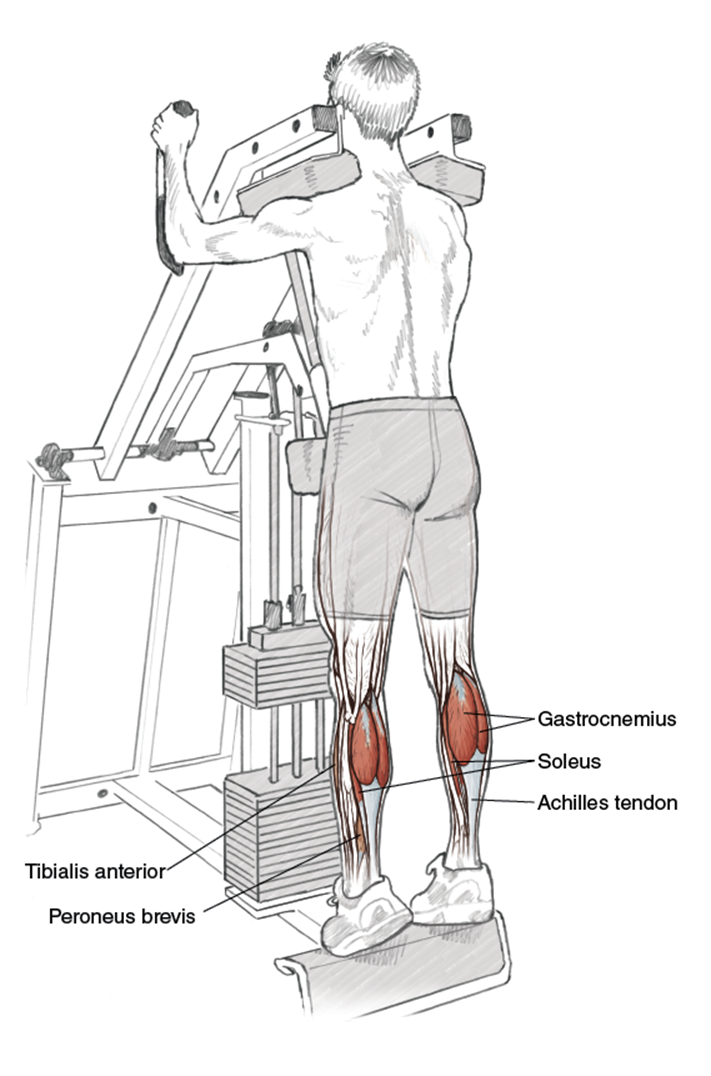

Muscles Involved

Primary: gastrocnemius, soleus

Secondary: tibialis anterior, peroneus brevis

Soft Tissue Involved

Primary: Achilles tendon

Running Focus

The standing heel raise is another exercise designed to strengthen the complex of calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus) and the Achilles tendon. Its emphasis is more on the gastrocnemius, the larger portion of the calf, than the soleus, but it does work the smaller muscle also. This exercise can be done during the same workout as the single-leg heel raise to really fatigue the calf muscles, or it can be done independently of the other exercises when the goal of the workout is to perform one exercise per body part.

The Achilles tendon and calf muscles take on much of the shock absorption and deflection after heel strike. When a runner races in lightweight shoes with a lower heel height than traditional trainers, the impact becomes more pronounced. To help minimize impact and aid in propulsion by moving the foot through its cycle, all runners should include exercises to develop calf strength in their training. These exercises can be performed during any stage of the running progression, with special emphasis during the racing phase if no injury has occurred.

Variation

Machine Seated Heel Raise

Similarities between the anatomy affected by the standing heel raise and seated heel raise abound, but it is the emphasis on the soleus muscle that differentiates the two exercises. When sitting, the gastrocnemius muscle is less involved in the exercise, allowing the soleus, despite its smaller size, to become the dominant calf muscle.

The strengthening of the soleus aids in the propulsive force of the takeoff phase of the running gait cycle. It also aids the runner who races (or works out) in racing flats to overcome calf pain and Achilles tendon strain during and following a race or a workout. The lower heel height of the flat or spike forces the Achilles tendon to stretch more than in running shoes. A strengthened and stretched soleus muscle helps prevent injury to the Achilles tendon by mitigating the extra stretch.

![]()

Plantarflexion With Tubing

Execution

1. Sit on the floor with legs fully extended in front of the body. A length of surgical tubing, an end in each hand, should extend underneath the foot, wrapping around the ball of the foot where the metatarsal heads are located. The tubing needs to be taut, with no slack, before the exercise begins.

2. Extend (plantarflex) the foot to full extension.

3. At full extension, hold the position for one second before pulling the tubing backward in a smooth, continuous fashion. The foot will be forced to dorsiflex and return to its initial position.

4. Repeat the push and pull of the exercise, adjusting tension throughout, until fatigue.

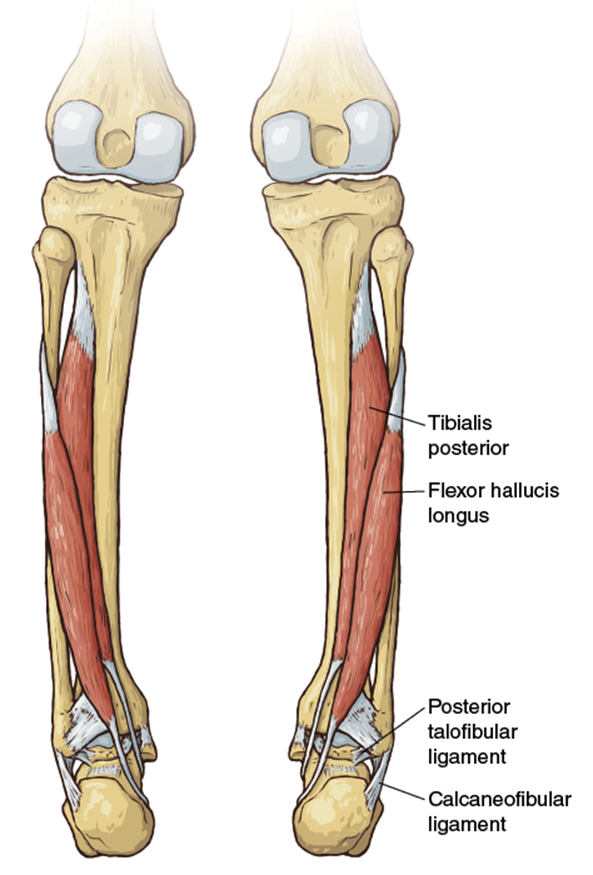

Muscles Involved

Primary: tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus

Soft Tissue Involved

Primary: posterior talofibular ligament, calcaneofibular ligament

Running Focus

In chapter 4, a discussion of the adaptations required for running at different speeds and terrains offers some insight into the role of the feet and ankles in running performance. This exercise promotes strength and flexibility of the foot and ankle to prevent injury when running on uneven terrain and aids in the support phase of the gait cycle.

Because this exercise is not weight bearing, it can be performed daily. It can function as a rehabilitative exercise to overcome an ankle sprain, or it can stand alone as a strengthening exercise to promote improved strength and flexibility. Because the exerciser controls the tension of the surgical tubing, the exercise can be made as difficult or as easy as possible for each repetition. The emphasis should be on a smooth but explosive movement with the appropriate resistance being provided by the tautness of the tubing, which can easily be adjusted by applying or lessening tension through gradually pulling or releasing the ends of the tubing held in each hand.

![]()

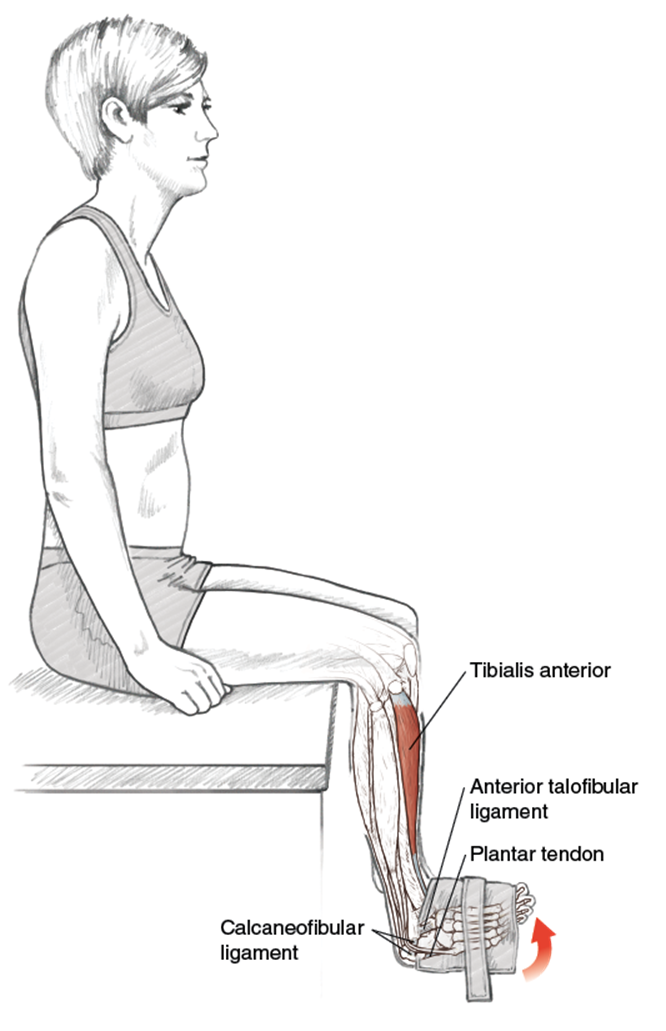

Dorsiflexion With Ankle Weights

Technique Tip

•The speed of the movement is not fast, but the muscles of the foot and the tendons of the ankle need to be dynamically engaged.

Execution

1. Sit on a table with knees bent and lower legs dangling. An ankle weight providing appropriate resistance is secured around the midfoot. The upper body is erect with hands by the sides providing balance only.

2. In a smooth but forceful motion, the foot dorsiflexes (points upward and back) toward the tibia to full extension. The lower leg remains bent at 90 degrees and does not swing to aid the foot and ankle in moving the weight.

3. Gently lower (plantarflex) the foot (it does not need to be fully extended) and repeat the exercise to fatigue. Switch the ankle weight to the other foot and repeat the exercise.

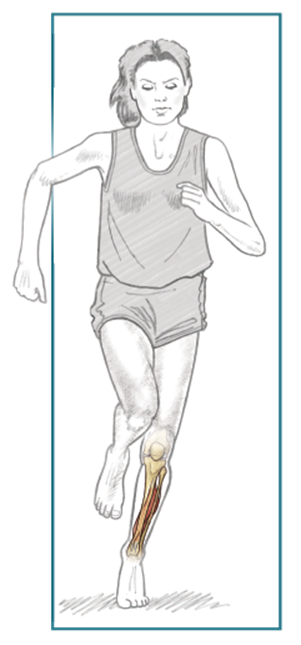

Muscles Involved

Primary: tibialis anterior

Soft Tissue Involved

Primary: anterior talofibular ligament, calcaneofibular ligament, plantar tendon

Running Focus

This is another non-weight-bearing foot and ankle exercise that can be done daily both as an injury rehabilitation exercise as well as to improve strength and flexibility. The amount of weight of the ankle cuff can be varied to fine-tune the goal of the exercise. For example, a heavier weight performed fewer times with fewer sets emphasizes the strengthening of the anatomy affected. A lighter weight allows for more repetitions and sets, which aids the flexibility and endurance of the anatomy affected.

Variation

Dorsiflexion With Tubing

This exercise can also be done with tubing, like the plantarflexion exercise. It can actually be done alternately by first plantarflexing the foot against the resistance of the tubing, and then immediately resisting when the tubing is pulled toward the body, until it is fully flexed and ready to plantarflex again.

![]()

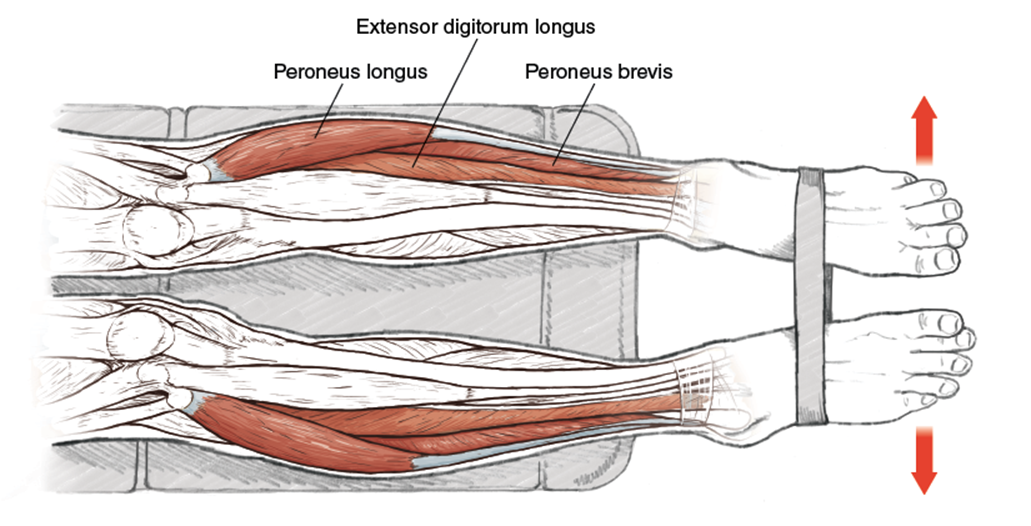

Foot Eversion With Elastic Band

Execution

1. Sit on a weight bench with the legs fully extended so that only the Achilles tendons, ankles, and feet are off the bench. Support the body by placing both hands on the bench behind the body. Wrap an elastic band tautly around both feet, which are plantarflexed, soles down, leaving approximately six inches of space between the feet.

2. Rotate the feet inward, dropping the big toes, and pushing outward with the feet against the resistance of the band. Hold for three to five seconds.

3. Relax the feet, rest for three to five seconds, and repeat.

Muscles Involved

Primary: peroneus longus, peroneus brevis, extensor digitorum longus

Running Focus

As mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, pronation happens as a result of movements on three planes, not just one. One of these movements is the eversion of the foot; during plantarflexion, eversion is controlled mainly by the peroneus longus, and in dorsiflexion, the peroneus brevis. This exercise is performed in the plantarflexed position because it is an easier movement, particularly for a runner who is an overpronator. Underpronators, also called supinators, benefit from this exercise because it is not the natural motion of their feet.

![]()

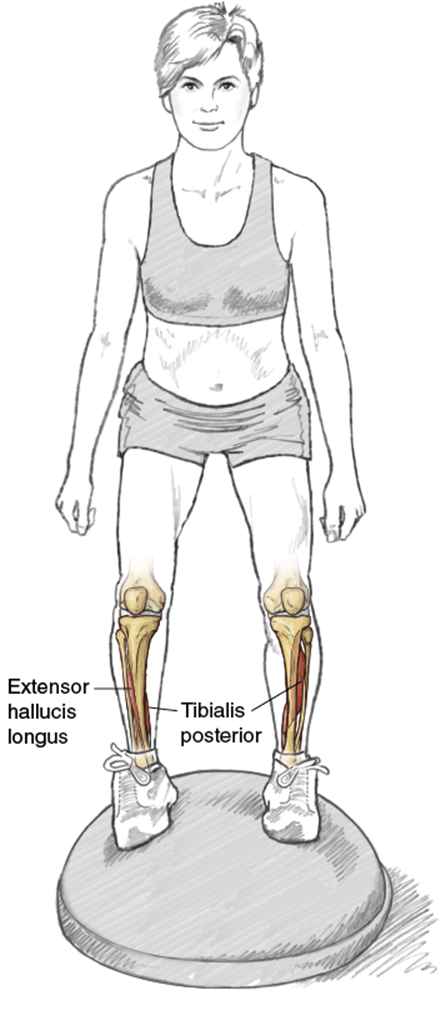

Foot Inversion on Bosu Ball

Execution

1. Step onto a properly inflated Bosu ball with the dome side up. Establish foot position to ensure a properly balanced body.

2. While standing on the Bosu ball with feet in an inverted position, perform any standing exercise from the book (see the Running Focus section that follows for details).

3. Fatigue sets in quickly, so stepping onto a flat surface as a break between reps on the Bosu ball can be taken as needed.

Muscles Involved

Primary: tibialis posterior

Secondary: extensor hallucis longus

Running Focus

Bosu balls are touted by fitness trainers as a tool for developing balance and proprioception. The development of balance and proprioception benefits the runner racing and training off-road, and the improved ankle strength and flexibility derived from the inverted position of each foot on the ball supports each foot through the gait cycle. The exercise performed is less important than the emphasis placed on maintaining balance on the Bosu ball. Given the curvature of the dome, the feet are in an inverted position on the ball throughout the exercise. For example, performing squats with dumbbells would be a good exercise to promote strengthening of the feet and ankles in the inverted position. Another less dynamic exercise would be to perform dumbbell curls. Or you could do one set or multiple sets of each. The emphasis is on the inverted position of the foot, but combining it with another exercise makes for a time-saving compound movement.

The use of the Bosu ball also adds a twist to normal strength-training exercises like dumbbell curls and dumbbell squats, making for a more varied and enjoyable strength-training routine. However, some exercises should not be performed on the Bosu ball. Specifically, exercises that require placing a lot of weight and torque on the knee joints (e.g., full squats with heavy weight) should be avoided.