In this, the final chapter of this book, we have come full circle. The major themes that we promised we would cover have been woven throughout the chapters. To complete this process we will revisit and expand on several important themes:

1. Unity and diversity: the genetic continuity of life as evidenced in model organisms.

2. Genetic and etiological heterogeneity

3. Genotype × phenotype associations

4. Pathogenesis: how do changes in DNA translate into disease?

The Human Genome Project and developing fields like proteomics give us unprecedented detail about the primary products of genetic coding. But we have seen how hard it often is to relate protein-coding genes to phenotypes, because of posttranslational processing and other events. Studies of model organisms can help direct our understanding of this complexity. In the next section, we will describe some of the experimental advantages of a select group of model genetic organisms and identify some of the key insights that have so far come from work with them.

This chapter will, therefore, be organized a little differently than the ones before it. We begin with Drosophila, not because it is the simplest, but because it is one of the first and most influential non-vertebrate models of genetic organization and function. Other important model organisms will then be introduced. We will discuss different mechanisms of pathogenesis.

Finally, we will see how advances in medical genetics promise to continue altering the face of medicine and the treatment of human genetic conditions.

Part 1: Bacteria, Fruit Flies, Mice, Fish: The Value of Model Organisms

The common fruit fly was one of the first organisms used to explore the mechanisms of inheritance. It became a model for the study of transmission genetics. In fact, some of the genetic insights from work with Drosophila are so fundamental that it is easy to take them for granted. But research with model organisms has continued to add dramatically to understanding our own genetics and development. A model organism offers some advantages—a known or small genome, simple develop, or easy rearing for mating studies and identification of mutations. Escherichia coli, yeast, round worms, and even simple plants allow us to see into the common genetic processes that are shared by all forms of life.

Most of the important discoveries that are the foundation of medical genetics could not have been made in humans. Fundamental genetic mechanisms often require large numbers of replications, controlled genotypes and environments, experimental manipulation of the genome or the developmental pathways each controls, and the use of tools like mutagenesis. Even when not outright illegal, these would be far too complex and time-consuming to apply to human families and populations. Thus, to ignore the contributions that model organisms have made to understanding human genetics is very shortsighted. Simple animals allow us to study in depth the many biological processes we share with them, and for those critical insights they deserve our respect.

Some examples of Nobel Prize winning genetic contributions using model organisms are shown in Table 16-1. The work of Thomas Hunt Morgan on basic transmission genetics earned the prize for defining the role of chromosomes in heredity. His experimental organism was Drosophila. Its ease of culture, special developmental characteristics like giant polytene (or endoduplicated) chromosomes, and the collection of mutations affecting all elements of development allowed Drosophila melanogaster to become the experimental model of choice. Using Drosophila, processes like the mutagenic effect of X-rays and the way genes control early embryonic steps in development were discovered. Similarly, the defined number of cells and the strict lineage of cell differentiation in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans illustrated how science can draw general insights from the special characteristics of a model organism.

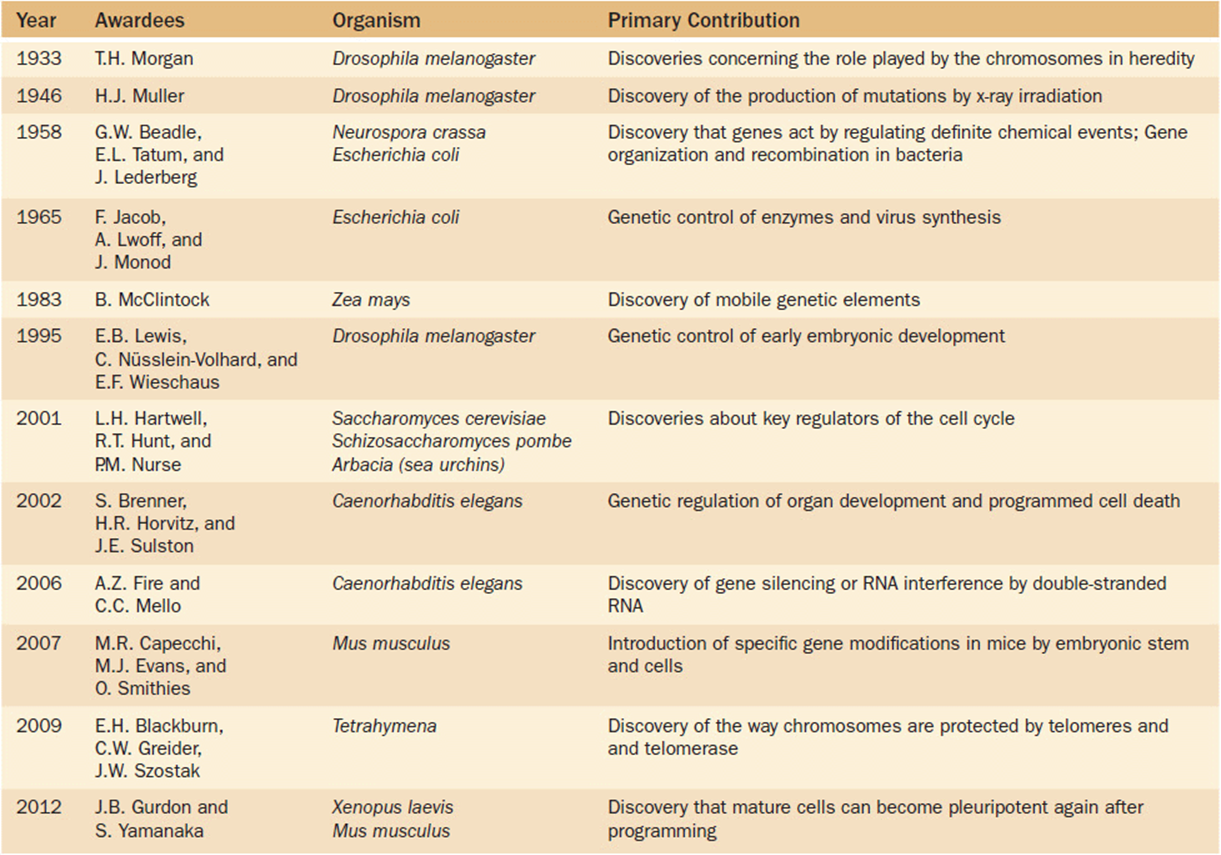

Table 16-1. Some Nobel Prizes for Genetic Research Using Model Organisms With General Applicability to Humans

A unifying concept here, indeed in all of biology, is “homology.” This biological term refers to the similarities found in structure or function due to shared derivation from a common ancestor. What we learn from model organisms often has a revolutionary impact on our understanding of our own species. The discovery of transposable elements in maize, chromosomal telomeres in Tetrahymena and yeast, and even the way that the genes in bacteria and molds control biochemical pathways illustrate the importance of model organisms. It is a significant theme, because it typifies the direction that biomedical research must continue to take for the future.

Model organisms are exactly that—they are models. But models are only useful to the extent that they give an insight into general processes or to the mechanisms at work in a system of prime interest, like human biology and development. Model organisms like Drosophila, C. elegans, and the others help us understand the general rules of genetic regulation that remind us about the continuity of life. When T.H. Morgan first began to study gene organization on Drosophila chromosomes, he could have had no idea that a discovery like the homeobox genes, which specify key elements of body organization in Drosophila, would open new avenues to understanding the developmental architecture of all organisms. Indeed, the so-called “bottom line” is that experimental research on model organisms will continue to be critically important for future advances in human genetics, because we share with all organisms a major part of our biological heritage.

The Common Fruit Fly, Drosophila melanogaster—Historical Contributions and its Continuing Importance as a Genetic Model

A landmark in the history of genetics was the discovery of a white-eyed mutation in a culture of Drosophila being used by T.H. Morgan to study population growth dynamics. This event began a long history in which Drosophilahas been used to explore many fundamental mechanisms of genetics. Genetic research is now stimulated by the extensive mutation collections of resource centers and the experimental innovation of Drosophila researchers. The creativity of researchers keeps opening new horizons. Of course, all of this would be essentially irrelevant were it not for the fundamental genetic similarity that Drosophila shares with all other species.

T.H. Morgan was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1933 for his work on the patterns of genetic transmission by chromosomes. The Nobel Prize can only be awarded to a living scientist, so Gregor Mendel was not eligible. But insights from Mendel, Morgan, and Morgan’s students including the later Nobel Laureate H.J. Muller, established the foundation for understanding mechanisms of gene transmission, linkage and sex-linkage, recombination, and changes in chromosome structure. Drosophila offers many experimental advantages. One is that the chromosomes of the Drosophila larval salivary glands undergo DNA replication for many cycles without cell division, creating giant chromosomes having about 1000 matched copies of the DNA strand lying together in a cable that shows significant chromosome detail. This makes it possible to map specific gene functions to specific physical regions of a chromosome, and changes in chromosome structure can be mapped precisely.

This would be an interesting historical footnote if the story stopped there. But it did not. In the years since then, Drosophila has become one of the most important experimental organisms for exploring the role of genes in development, physiology, and behavior.

In part this is because many gene and special chromosome mutations have been identified over the years. These allow experiments to target processes that are difficult to match in other organisms. It also made it possible to apply the techniques of recombinant DNA when they first became available, and the discoveries from that work identified genetic mechanisms that were found to be in common with other organisms.

Drosophila has a genome of about 13,600 genes. About a quarter of its genome is made up of highly-repetitive DNA and several dozen kinds of transposable elements. Some of the earliest work on transposable elements, the P-elements of “mutator activity” or “hybrid dysgenesis,” was done with Drosophila. P-elements have now become a powerful experimental tool for targeted mutagenesis and other genome manipulations.

At the other end of the phenotypic spectrum, research using Drosophila explored the genetic basis of quantitative traits. These are traits that vary in expression because the effect of each gene can be enhanced or masked by environmental factors affecting the same trait. Using carefully controlled experiments that factored out environmental effects, experiments with Drosophila showed that even apparently complex expression could often be explained by genetic variation in a relatively small number of contributing genes. This perspective should change a physician’s approach to complex traits. Although variable in presentation, a condition may still be traced to a predictable biological process.

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature has moved to change the taxonomic name of this genetic landmark organism to Sophophora melanogaster. It is a change that may be justified taxonomically but is criticized by the genetic research community. This may be a rare example of consistency and stability of the literature being more important to the growth of science than is taxonomic precision. It is a change that is likely to be ignored by most geneticists for a long time. But do not be confused if you find this name in your future journal reading.

A Bacterium, Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli is one of the most important model systems for understanding simple genome organization and is central to areas like recombinant DNA technology development. On the other hand, some strains of E coli cause food-borne illness that can be quite serious. As a species, its genome is exceeding diverse, but the strains, like E coli K12, used in microbial genetics are restricted in number. A representative genome was first reported in 1997. It is a circular DNA molecule of 4.6 million base pairs with 4288 protein-coding genes, 7 rRNA genes, and 86 tRNA genes. But the number of genes varies among strains, and some genes may have come from horizontal transfer from other organisms. These variables add to the utility of E coli as an experimental organism for genetic study.

Joshua Lederberg and Edward Tatum discovered the process of bacterial conjugation in E coli, and Seymour Benzer utilized E coli and the T4 bacteriophage to study the linearity of gene structure in the genome. A foundation of modern biotechnology can be traced to work with plasmids and restriction enzymes in E coli. One early application of recombinant DNA technology was the production of human insulin from E coli.

Baker’s Yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Yeast is a developmentally simple eukaryote, with a life cycle that has both haploid and diploid phases. Its short generation time allows experiments to be carried out efficiently using techniques, like plating colonies on petri dish media, that parallel some of those available for bacteria. In addition to employing mutations to dissect components of a developmental process, Saccharomyces is being used to study signal transduction pathways that alter cell phenotypes.

Although the Saccharomyces genome was completely sequenced by 1996, geneticists are still uncertain how many functional genes are present in its genome. It is likely that the number is about 6000 or so, but many hypothetical genes have functions that are not yet known. In addition to protein-coding genes, there are many noncoding RNAs, including 274 tRNA genes and RNAs for ribosome processing, intron splicing, and other cellular processes. About 20% of the loci lead to lethality when mutated. Recombination rates are higher than those for most other fungi, and good genetic maps are available for a large number of loci.

The proportion of repeated sequences is much lower than that found in most multicellular eukaryotes (see Chapter 4). About 4% of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome is composed of transposable elements. The virus-like retroelement Ty is found in about 50 copies in each genome. Intact Ty elements can pair and recombine even when they are located on different chromosomes, resulting in frequent reciprocal translocations and other chromosomal aberrations.

There are two mating types, a and α. Signal transduction pathways can be activated by pheromones that are released by cells of one mating type and then bind to receptors on the other mating type. This activates an intracellular cascade that phosphorylates, and thus activates, a transcription factor. This in turn activates the genes needed for arresting the G1 cell cycle and for cell fusion and nuclear fusion required for mating. This type of signal transduction pathway studied in yeast is highly conserved in eukaryotes.

A Nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is a simple eukaryote with precisely 959 cells in a female, which is a functional hermaphrodite, and 1031 cells in a male. The cell lineage relationships in both sexes are now completely mapped (Figure 3-12). Six founder cells give rise to all the cells of the adult, and mutations that alter cell lineage progression are a valuable tool for developmental analysis. Adults are about 1 mm long and can be handled with techniques that resemble those used to culture bacterial cell colonies. Since it is transparent, mutations affecting its internal anatomy and development can be studied easily. Each mating can yield hundreds of progeny, and it shares many of the experimental advantages that have benefited work with Drosophila. The sequence of its approximately 14,000 gene genome was completed in 1998. Insights into genetic control of development using Caenorhabditis elegans were recognized by the Nobel Prize to Sydney Brenner, Robert Horvitz, and John Sulston in 2002.

One special benefit of C elegans as an experimental model is the fact that its cell lineage during normal development is strictly defined (see Figure 3-12). The specific fate of each progenitor cell has been mapped. With this map it has been possible to define inductive signals between one cell and another, the signal transduction pathways of the recipient cell, and genetically programmed cell death events. Gene expression in C elegans has some unexpected elements, such as examples of polycistronic transcription like that seen in bacteria. One process discovered in C elegans is RNA-mediated interference (RNAi). When used as an experimental technique, it allows researchers to study the function of targeted genes by silencing their expression.

The Zebrafish, Danio rerio

The zebrafish, Danio rerio, shares many characteristics with other model genetic systems. They have a short generation time and they lay several hundred eggs in each reproductive cycle. An important advantage for researchers is that the embryos are relatively large and transparent. This means that internal developmental changes can be observed easily. The precursors to major organs become visible through the body wall within about 36 hours after fertilization, and hatching occurs up to about 36 hours later. The genome of D rerio has been sequenced and many genetically-characterized strains are available to researchers. Among these are strains that allow study of diurnal sleep cycles, which are similar to those of mammals.

Using anti-sense technologies, important aspects of development can be studied. This technique uses Morpholino oligonucleotides. These synthetic nucleotide chains of RNA or DNA bind to complementary sequences when injected into an embryo. By binding to a complementary sequence in a cell, they effectively inactivate it and, thus, mimic a mutation. This reduces gene expression in the cell and its descendants. The technique allows the equivalent of targeted mutagenesis to explore genetic effects on development of a vertebrate with many homologies to human biology.

The House Mouse, Mus musculus

As a mammal that shares many aspects of physiology and development with humans, it is not surprising that our genomes are similar in size (about 3 billion bp) and content. In fact, extended regions of gene sequence similarity have been identified showing that even the organization of our genomes retains extensive homology. Gene sequence similarities are also reflected in functional parallels. Thus, homology makes the house mouse an especially valuable model for understanding human genetics. Advanced cellular and molecular techniques can be combined readily with more traditional genetic mating systems. One specific example is the use of Mus to develop models of many human genetic diseases.

As an experimental model, they benefit from a relative short life cycle (8 or 9 weeks), small body size, and comparatively large litters of offspring. Transgenic manipulation allows complex processes to be isolated and studied. With nuclear injection, one can add specific genes to the genome. Targeted mutagenesis can change or inactivate a locus of choice. In contrast to the defined cell lineage outcomes associated with cells of C elegans, cells in the early embryonic stages of Mus retain totipotency, or developmental flexibility. It is therefore possible to generate chimeras, composed of cells derived from two or more separate genotypes. Literally hundreds of single-gene mutations are now available in strains with well-documented genetic backgrounds, providing a rich resource for advanced experimental design. Among these are the Hox genes, homologous to the homeobox genes first described in Drosophila, which define critical elements of body plan in all multicellular organisms (Figures 13-19 and 13-20).

A Model Plant, Arabidopsis thaliana

Arabidopsis thaliana (Figure 16-1) is a small weed with no special economic importance, other than being a model plant for genetic studies. Its small size, five pairs of well-banded chromosomes, and relatively tiny genome offer an ideal organism in which to study the molecular biology and genetic control of processes like growth, biochemical pathways, and development of a plant. Its genome was published in 2000. Transposable elements that had originally been identified in corn can be introduced into A thaliana cells and become integrated into its genome. Agrobacterium is the biological agent both for this process and for transformation by plasmid DNA called T-DNA. Insertional mutagenesis is a powerful technique for generating mutations to study biochemical and developmental processes.

Figure 16-1. Arabidopsis thaliana, a model plant. This plant has no true agricultural or ecosystem value. Its importance exists in its role as a research organism. (© Jeremy Burgess/Photo Researchers.)

Genetic analysis has yielded insights into the control of development by plant hormones and in response to light, a complex of processes known as photomorphogenesis. Although plants do not contain a homeobox like that in animals, they have a functionally equivalent group of genes that code for DNA-binding transcription factors. Surprisingly, a degree of partial homology between this plant’s steroid-like gene and mammalian genes of the steroid pathway suggests that future research may uncover even more fundamental genetic connections among distantly-related organisms.

What Does This Reveal About Human Disease?

Comparative genomics hybridization is the discipline of studying genetic relationships across species. While information can be obtained in one species and applied to another, translating that information into practical applications is much more difficult. First, animal physiology is not an exact replica of that in humans. Caution has to be taken before a treatment in a model organism is verified in humans. Second, even though a particular gene may be homologous by sequence between two organisms, it is not necessarily true that the gene will perform the same function in each nor will phenotypes be predictable. For example, mutations in the eya gene produce a phenotype in Drosophila that is “eyes absent.” But mutations in the homologous human gene EYA1 produces a phenotype of branchio-oto-renal syndrome—a condition associated with malformations of the branchial arch structures, kidneys, and ears/hearing. This then is a double-edged sword. While caution has the be taken in making any projections or extrapolations, it is impressive to consider that studies of the veins in fruit fly wings can give critical insights into processes like cancer, stress responses, and neural networks!

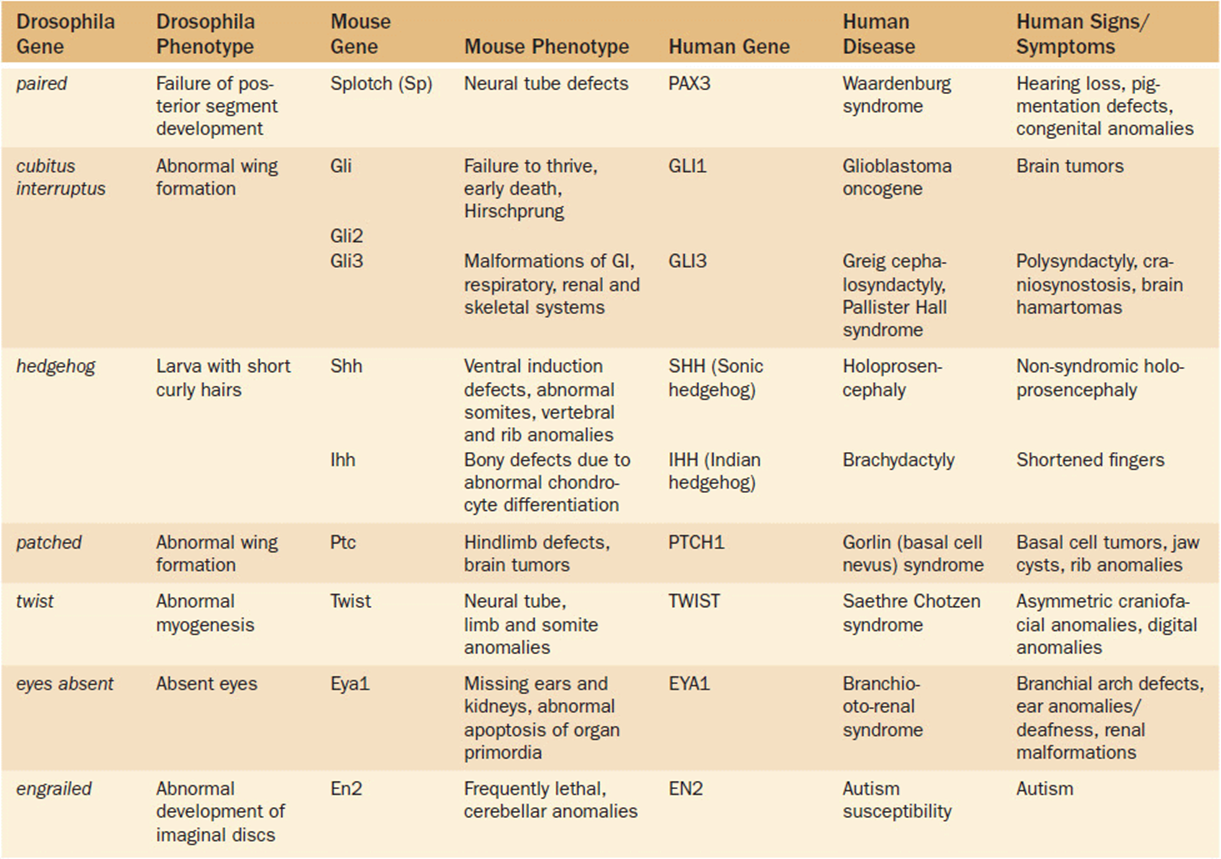

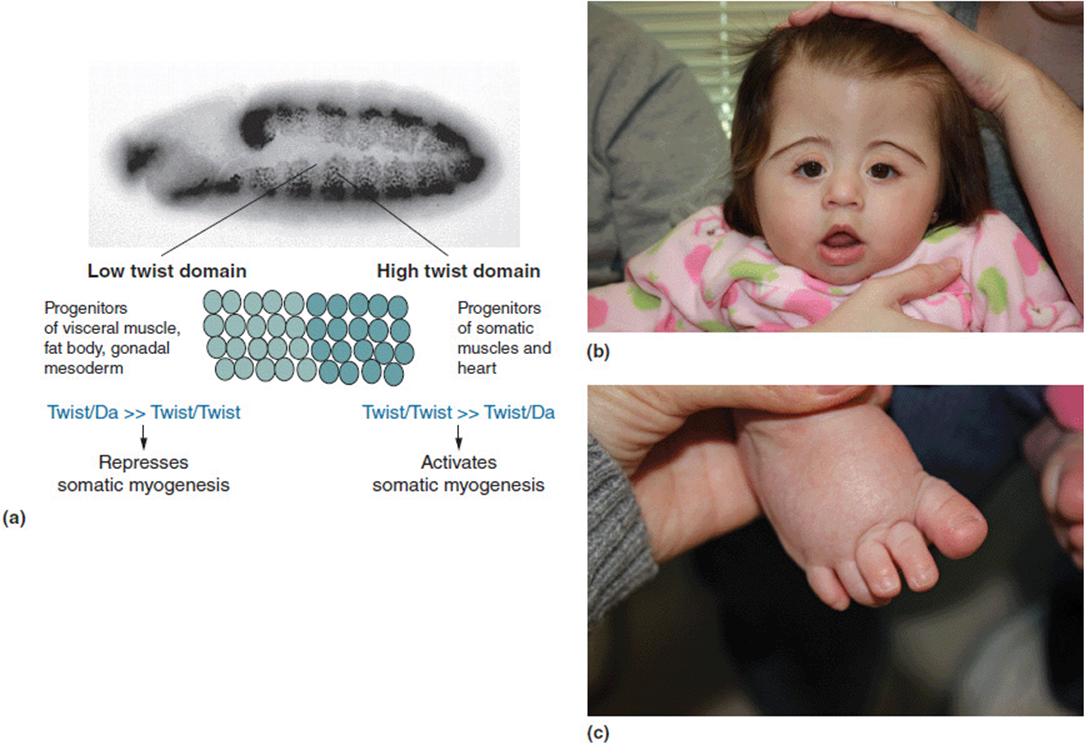

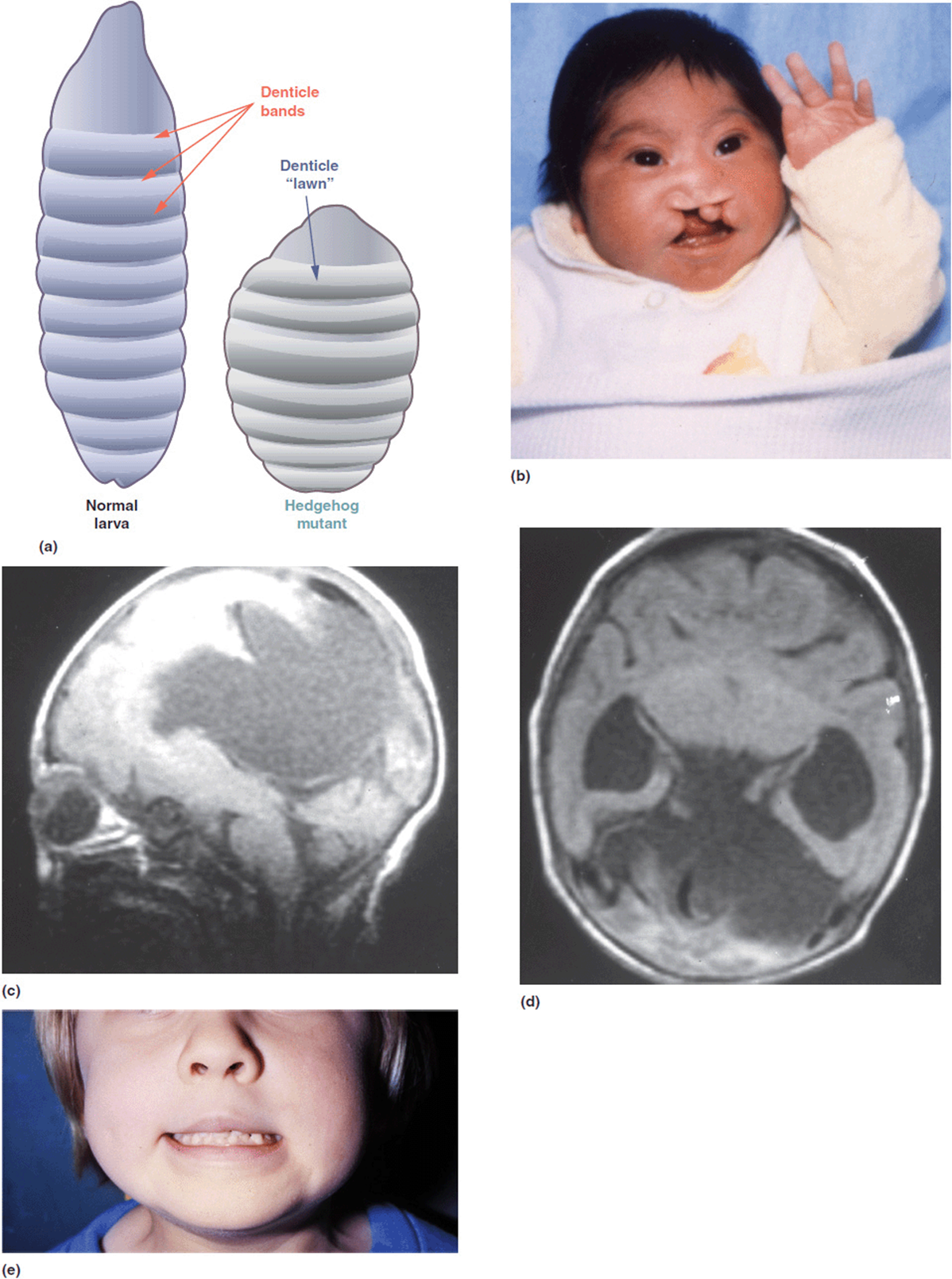

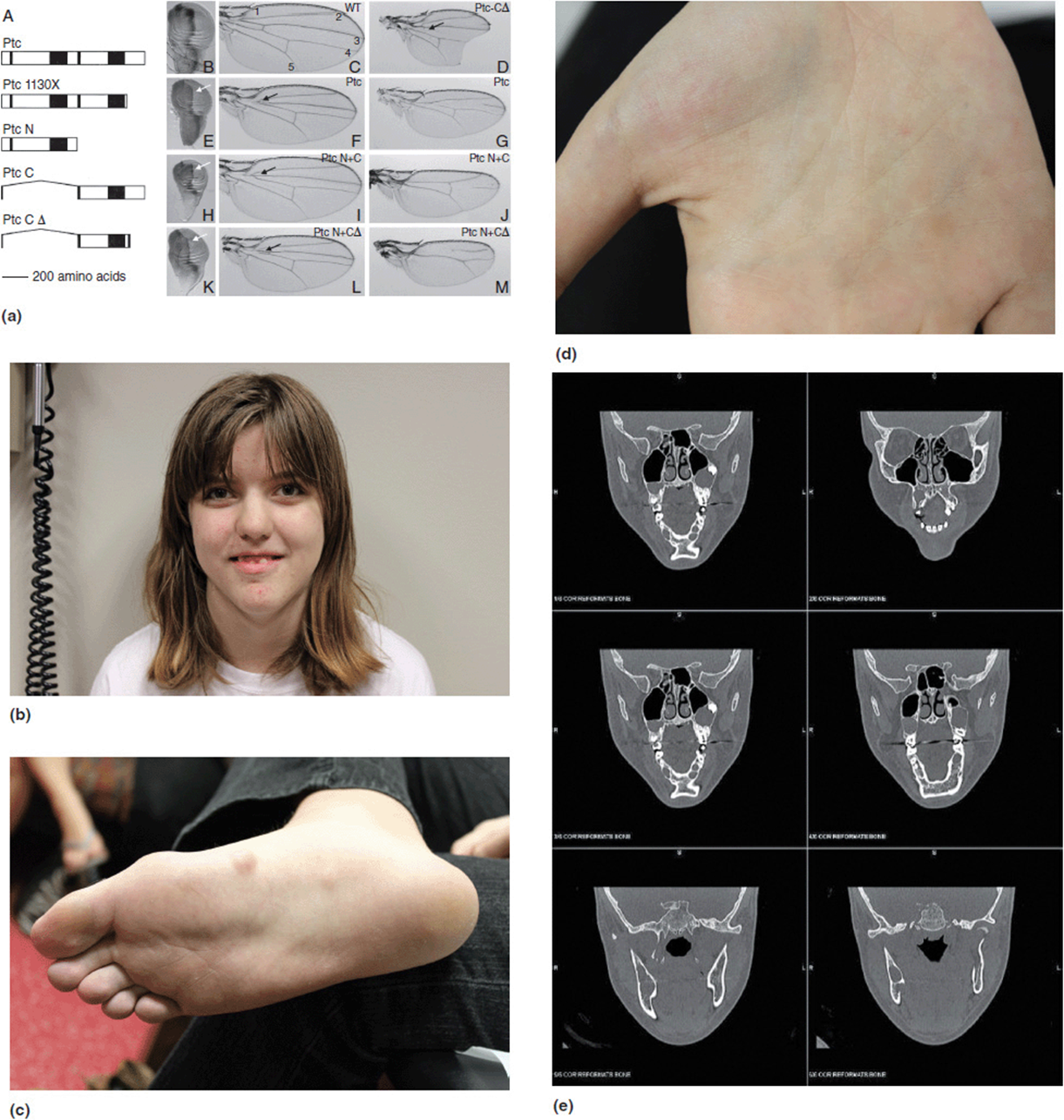

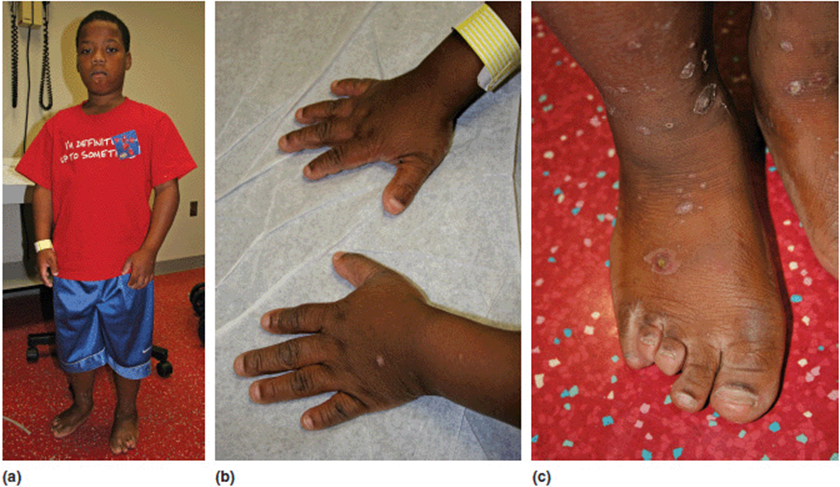

Table 16-2 lists several other such known relationships. We will describe just a few of these in more detail. Saethre-Chotzen syndrome is a disorder characterized by craniosynostosis and other craniofacial anomalies as well as digital changes (Figure 16-2 b, c). It is caused by a mutation in a gene known as TWIST which is a transcriptional regulator. The Drosophila homolog gene is designated twist. Mutations in this gene in Drosophila produce segmentation defects of myogenesis (Figure 16-2 a). The hedgehog gene in Drosophila gets its name from a mutation that produces short bristly hairs on the larvae that are reminiscent of a hedgehog (Figure 16-3a). The human homolog has been termed Sonic hedgehog (SHH). Mutations in SHH have been shown to cause heritable non-syndromic holoprosencephaly (Figures 16-3 b-d). The phenotypic spectrum of SHH in humans may be as mild as only showing a single central incisor (Figure 16-3 e).

Table 16-2. Examples of Different Phenotypes Associated with Homologous Genes Across Species

Figure 16-2. (a) Drosophila larva with abnormal myogenesis due to twist mutation. (b) Craniofacial changes in a young girl with Saethre Chotzen with a known TWIST gene mutation. (c) Broad great toe in same patient. (a: Reprinted with permission from Castanon I, Von Stetina S, Kass J, et al. Dimerization partners determine the activity of the Twist bHLH protein during Drosophila mesoderm development. Development 2001 128:3145-3159.)

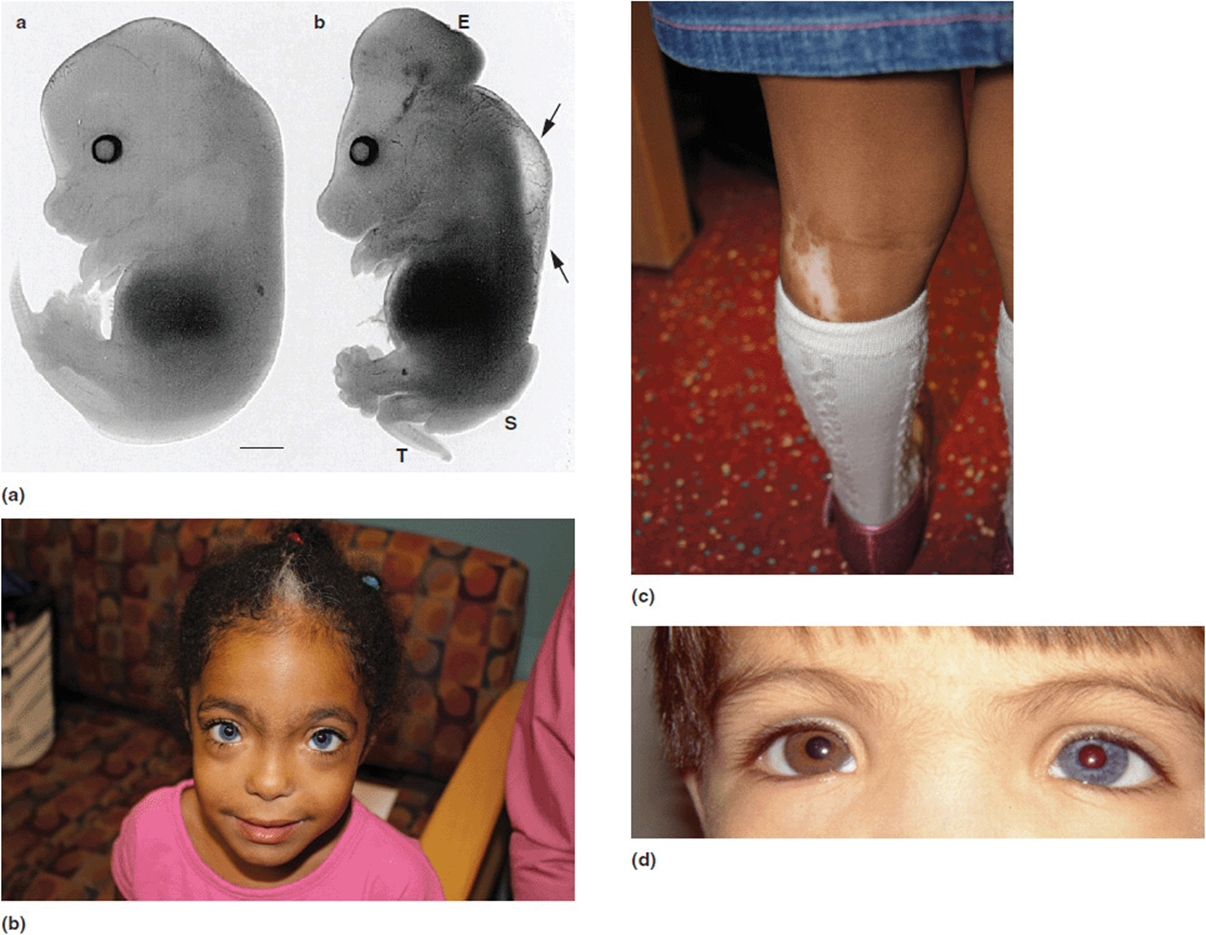

Figure 16-3. (a) Normal Drosophila larva on left. The larva on the right has a mutation in the hedgehog gene. (b) Patient with holoprosencephaly with severe bilateral cleft lip and palate. He has a positive family history with 2 half-brothers also affected. (c, d) Brain MRI of the boy in frame b showing incomplete ventral induction (separation of midline)—semi-lobar holoprosencephaly. (e) Their mother has a minor expression of the condition as a single central incisor. She and all 3 boys have an SHH mutation. (a: Reprinted with permission from van den Brink GR. Hedgehog Signaling in Development and Homeostasis of the Gastrointestinal Tract Physiol Rev October 2007 87:(4) 1343-1375; doi:10.1152/physrev.00054.2006.)

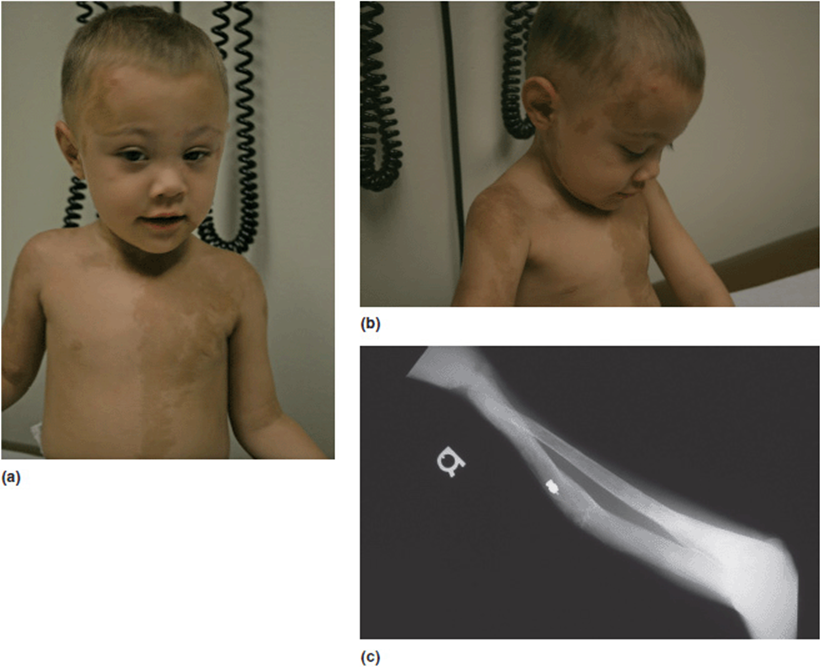

Basal cell nevus syndrome (previously called Gorlin syndrome) is associated with craniofacial dysmorphisms, jaw cysts, palmar and plantar pits, and the propensity to develop basal cell carcinomas (Figure 16-4 b-d). It is caused by a gene called PTCH1. The Drosophila homolog is the patched gene. Mutations in this gene cause a variety of fly wing anomalies (Figure 16-4 a). One last example is that of Splotch mutations in mice which produce defects in neural tube development (Figure 16-5 a). The human homolog is the homeobox gene PAX3. PAX3 mutations are seen in some patients with Waardenburg syndrome, although there is genetic heterogeneity for this condition. Waardenburg syndrome is characterized by neurosensory hearing loss and telecanthus (lateral displacement of the inner canthi of the eyes). Patients with Waardenburg syndrome also will have a variety of pigmentary changes including a characteristic “white forelock” of hair, iris heterochromia, and poliosis (patchy hypopigmentation of the hair and skin). These features are shown in Figure 16-5(b-d).

Figure 16-4. (a) Multiple wing malformations associated with patched mutation. (b) Adolescent girl with Gorlin (basal cell nevus) syndrome. She has a confirmed PTC mutation. Patients with Gorlin syndrome are reported to have broad facies, frontal bossing and prominent jaws. (c) Basal cell tumors on the foot. (d) Palmar pits. (e) Head CT scan demonstrating odontogenic keratocysts (in the jaw). (a: Reprinted with permission from Johnson RL, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. In Vivo Functions of the Patched Protein: Requirement of the C Terminus for Target Gene Inactivation but Not Hedgehog Sequestration, Molecular Cell, volume 6, issue 2, August 2000, pp 467-478, ISSN 1097-2765, 10.1016/S1097-2765 (00)00045-9.)

Figure 16-5. (a) Mice embryos. The one on the left is normal. The one on the right has a Splotch mutation and is showing defects of neural tube development. (b) Young girl with Waardenburg syndrome. She presented with neurosensory hearing loss. She has a known PAX 3 mutation. (Note white hair patch and dystopia canthorum). (c) Hypopigmented area of skin on her leg. (d) Young boy with Waardenburg syndrome. Note iris heterochromia. (a: Reprinted with permission from Conway SJ, Henderson DJ, Kirby ML, et al. Development of a lethal congenital heart defect in the splotch (Pax3) mutant mouse Cardiovasc Res (1997) 36(2): 163-173 doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(97)00172-7.)

Part 2: Pathogenesis of Disorders

From the standpoint of diagnostics, the goal is to find the etiology. Etiology simply means the cause of the condition. Knowing what the cause is, is the first step in arriving at several important conclusions about a condition. Besides simply knowing the name of a condition, an etiologic diagnosis is helpful in many ways we have already discussed, such as estimating recurrence risk, prognosis, co-morbid conditions, natural history, and other factors.

A related, but distinct, concept is that of pathogenesis. Pathogenesis defines the mechanism whereby changes in the genome translate into physical traits. That is, how does a mutation change the gene function and thus produce a recognizable phenotype? It is absolutely necessary that pathogenesis is understood if targeted therapies are to be designed for genetic disorders.

George Beadle and Edward Tatum (after his work with Lederberg) won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1958 for work they began in the early 1940s. Using mold as their model organism, they set out to identify the connection between genes and enzymes. They hypothesized a one-to-one relationship between genes and specific enzymes. They predicted that it should be possible to generate mutants in specific enzymatic reactions and thus produce a phenotypic effect. This pioneering work was among the first attempts to identify pathogenesis at a molecular level. This type of relationship makes complete sense: mutation leads to a defective enzyme, which leads to disrupted biochemical reaction, which leads to disease. If only everything were that simple! Through the course of this book we have covered many examples of genetic disorders in which the pathogenesis is not that of product insufficiency. Many other pathogenic mechanisms exist whereby disease results.

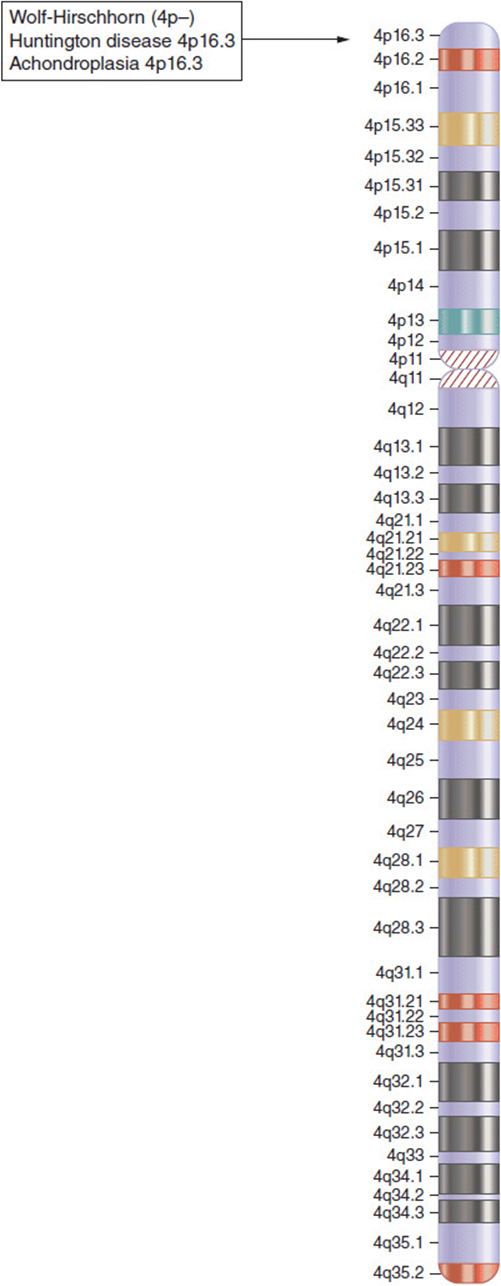

Along these lines, consider three conditions that have been previously discussed in different contexts. Wolf-Hirschhorn (WHS) is a multiple anomaly syndrome caused by a terminal deletion of the short arm of chromosome 4 (Chapter 5, Figure 5-49d). Achondroplasia is an autosomal dominant skeletal dysplasia. Patients with achondroplasia have a disproportionately short stature and macrocephaly (Chapter 6, Figure 6-18a). Huntington disease is an autosomal dominant adult-onset neurodegenerative condition that exhibits progressive dementia, involuntary movements, and neurologic decline usually beginning in the 40s or 50s (Chapter 6, Figure 6-24a).

So what is the link between these conditions? Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS) is a chromosomal deletion syndrome (4p-). The multiple congenital anomalies in these patients are produced by absence of one of the copies of some of the deleted genes. Notably, the genes for achondroplasia and Huntington disease are in this same region and are typically deleted in patients with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (Figure 16-6). However, patients with WHS do not have achondroplasia nor do they develop Huntington disease in adulthood—and yet these are both dominant conditions. The answer lies in the pathogenesis of the conditions.

Figure 16-6. Idiogram of chromosome 4. The chromosomal location of Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome, Huntington disease, and achondroplasia are all at the terminal end of the short arm of chromosome 4 (4p16.3).

As noted, the congenital anomalies seen in WHS are caused by the missing products of some of the genes in that region. But in achondroplasia, the bony disorder is produced not by missing protein product, but by mutations that generate a structurally abnormal protein. As mentioned, WHS patients also do not develop Huntington disease as they age. In Chapter 12 (Atypical Modes of Inheritance) we identified the pathogenesis of Huntington disease as being due to an expanding trinucleotide repeat within the gene. The expanded repeat results in excess production of molecular products that are actually cytotoxic. The result is acquired cell death of the basal ganglia and resultant progression of neurologic dysfunction. So in neither achondroplasia nor Huntington disease is the pathogenesis deficiency of product, but something completely different. In all three cases it would make sense that strategies to address therapies for each would have to take markedly different approaches!

Examples of Types of Pathogenic Changes

So it is clear that when a mutation occurs in a specific gene, it can evoke pathologic changes through a variety of different mechanisms. For illustration purposes we will discuss just a few of these in more detail here.

1. Missing/nonfunctional protein. This, of course, is the classic example as identified by Beadle and Tatum. As was discussed in Chapter 8 (Metabolism) most inborn errors of metabolism are recessive disorders. Typically enzyme systems carry a very large capacity such that it often takes enzyme levels to fall below 5% of normal for there to be clinically observable effects. Thus the pathogenesis for inborn errors of metabolism is simply that of absent enzyme activity. Both alleles must be disabled before problems occur.

2. Abnormal protein folding. Sickle cell anemia was discussed in Chapter 2. In this situation, a single nucleotide change (c.20A > T) results in a single amino acid change (p.Glu6Val) of the beta globulin protein. This specific change results in abnormal folding of the hemoglobin molecule which in turn distorts the shape of the red blood cell (RBC) from a smooth “donut shaped” cell to an irregular cell that has been described as looking like a sickle (Figure 2-35). These sickled RBCs are prone to occluding the smaller blood vessels as they pass through the tight passages of the capillary beds. As such, a large part of the pathogenesis of sickle cell disease is micro-vasculature occlusion.

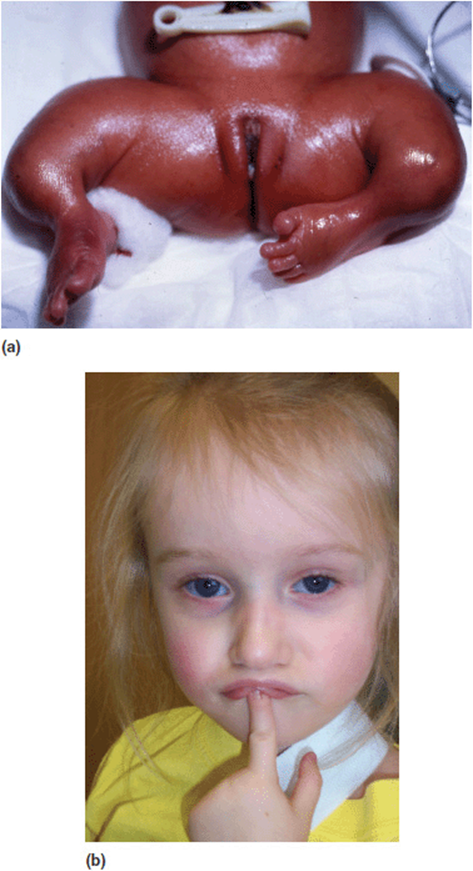

3. Disruptive protein. Type I collagen is a trimeric protein. It is assembled from three polypeptide chains woven into a triple helical protein. Type I collagen comprises two alpha-1: (I) chains and one alpha-2 (II) chain. Abnormalities of type I collagen are associated with phenotype of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI)–sometimes referred to as “brittle bone” disease (Figure 16-7). Pathogenic changes in any of the physiological processes of type I collagen production can result in OI. This would include problems with transcription, translation, posttranslational modification, assembly, or transport.

Figure 16-7. (a) Lower limbs of an infant with severe osteogenesis imperfecta. (b) Face of a young girl with milder osteogenesis imperfecta. Note the blue sclera.

Mutations in either of the procollagen genes that produce structurally abnormal proteins will have an abnormal dominant negative effect resulting in a more severe phenotype. One interesting phenomenon in the pathogenesis of OI is that of “protein suicide”. Small intragenic deletions in the pro-alpha-1-collagen gene produce a shortened protein that will prevent normal folding. Not only are these molecules nonfunctional, but they are rapidly degraded. This will actually result in a milder clinical form of OI. (It should be noted that the same process happens when there is an early frameshift mutation or whole gene deletion).

4. Gain of function. It is intuitive that mutations can exert their effects by disabling normal gene function. But it is important to remember that biological systems occur in a balanced equilibrium. Overproduction can be as problematic as insufficient product. Indeed a number of activating mutations have been characterized. Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO) is a recognizable syndrome that exhibits mildly shortened stature, moderate obesity, rounded facies, short neck, short metacarpals and metatarsals, subcutaneous calcium deposits, and endocrine abnormalities. Some patients with AHO will have cognitive deficits (Figure 16-8). The etiology of AHO has been shown to be due to mutations in the alpha subunit of the secondary messenger G protein (GNAS1) that decreases gene function. McCune-Albright syndrome is characterized by polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, clonal patches of skin hyper pigmentation, and a variety of endocrine abnormalities including isosexual precocious puberty (Figure 16-9). McCune Albright syndrome is also caused by mutations in GNAS1. What is different from this condition and AHO is that mutations in McCune Albright syndrome are activating mutations. Thus from a pathogenic standpoint, the two conditions are inverse disorders. It is fascinating to note that Dr. Albright described both of these conditions independently prior to molecular identification of etiology. Little did he—or anyone else—suspect that they were in fact allelic disorders! One last thing worth mentioning is that patients with McCune Albright syndrome are always mosaic for the mutation. This explains many things about the condition including the patchy pigmentation. It is likely then that germ line activating mutations of GNAS1 are not compatible with life.

Figure 16-8. (a) Adolescent male with Albright hereditary osteodystrophy. He has mildly disproportionate short stature and (b, c) his hands and feet demonstrate brachydactyly. The 3/4/5 toes are especially short. This patient has a confirmed GNAS1 mutation.

Figure 16-9. (a, b) Young boy with McCune Albright. Note clonal hyper-pigmented patches of skin. (c) Fibrous dysplasia of the radius. This young man had confirmed mosaicism for GNAS1 mutations on skin biopsy.

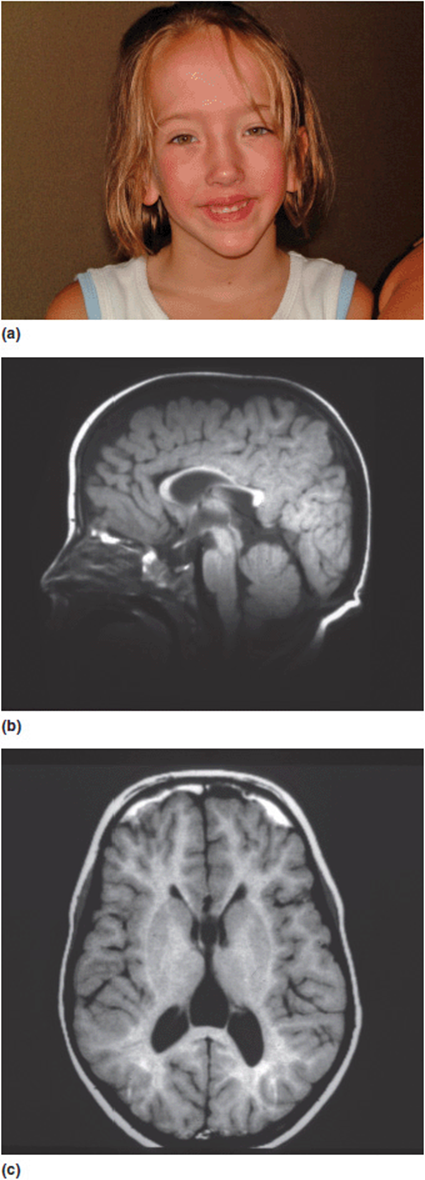

5. Abnormal regulation of other genes. Sotos syndrome is a well-described multiple anomaly syndrome. The major features of Sotos syndrome are somatic overgrowth, advanced osseous maturation, characteristic facies (down-slanting palpebral fissures, triangular chin, apparent hypertelorism), relative and absolute macrocephaly, supra-nuclear (central) hypotonia, and neurodevelopmental/neurobehavioral problems (Figure 16-10a). The vast majority of patients with Sotos syndrome also have a unique pattern of changes noted on MRI scans of the brain (Figure 16-10 b, c). Over 90% of patients with Sotos are found to have a mutation in a gene designated NSD1. NSD1 is a histone methyl-transferase implicated in transcriptional regulation. It has multiple functional domains that regulate several other genes such as the estrogen receptor, thyroid hormone receptor, retinoic acid receptor, retinoid X receptor, and nuclear receptor interaction domains. The pathogenesis of Sotos syndrome thus has to be assessed not by looking at the gene itself, but by evaluating all of the other genes it influences. Current estimates suggest that NSD1 may directly interact with over 30 other loci.

Figure 16-10. (a) Young girl with Sotos syndrome with typical facial characteristics. (b, c) Sagittal and axial MRI images of the brain of a child with Sotos syndrome showing characteristic changes.

These are just a few of the known pathogenic mechanisms. Table 16-3 lists several other types of changes. By no means is this list all-inclusive, but it does provide some insight into the various possible pathogenic mechanisms to be considered. To reiterate an earlier point, the understanding of pathogenesis is central to designing targeted therapies. True personalized medicine will occur when individuals have correct clinical diagnoses coupled with a knowledge of molecular etiology and an understanding of the pathogenesis of their specific mutation. Only then can therapy be truly customized to the individual.

Table 16-3. Different Pathogenic Mechanisms (Types of Pathogenesis)

Missing/nonfunctional protein

Abnormal stereochemistry/3-dimensional protein folding

Disruptive protein

Gain of function (toxic)

Abnormal regulation of other genes

Tumor suppressor functions

Selective cell death (apoptosis)

Abnormal DNA repair

Expanded trinucleotide repeats

loss of function

gain of function

dominant-negative effects

Epigenesis

Abnormal regulatory RNAs

Disorders of chromatin remodeling

Abnormalities of transcription factors

Abnormal chaperone proteins

Abnormalities of protein degradation machinery (ubiquitin-proteosome system)

Part 3: How Complex Can Things Be?

Another important unifying concept to review is that genes in humans are seldom “simple.” Remember that humans have about 22,000 functioning genes. This is less than some invertebrates and plants. The tremendous complexity of human biology comes from the variety of modifications that happen in gene expression beyond the genomic code itself. Also genes do not operate in isolation. As has been stressed many times before, gene × gene interactions are abundant and complex.

Take for example cystic fibrosis (CF) (see Chapter 4 including Figure 4-21). Almost everyone who has studied human genetics has heard of this condition and is aware that the condition has autosomal recessive inheritance. Few, however, understand the extreme complexity of the genetics of this condition. While it is correct that the condition does show autosomal recessive inheritance, molecular studies of the condition have revealed many different layers of understanding of its expression beyond simple Mendelian segregation.

In the current clinical setting, molecular analyses of the CF gene can provide so much more information. A complete understanding of the genetics of CF would include a description something like this:

1. Cystic fibrosis is caused by mutations at a single known locus (i.e., no locus heterogeneity). The gene is designated as CFTR. It is at chromosome locus 7q31.2.

2. The CFTR gene has 250,000 base pairs and 27 exons. During transcription, the introns are excised and the exons are assembled into a 6100 base pair mRNA transcript, which is translated into the 1480 amino acid sequence of the CFTR protein.

3. The gene codes for a protein product, the CF trans-membrane conductance regulator. This protein is a chloride channel protein found in the membranes of exocrine cells of the pulmonary epithelium, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, and the genitourinary tract.

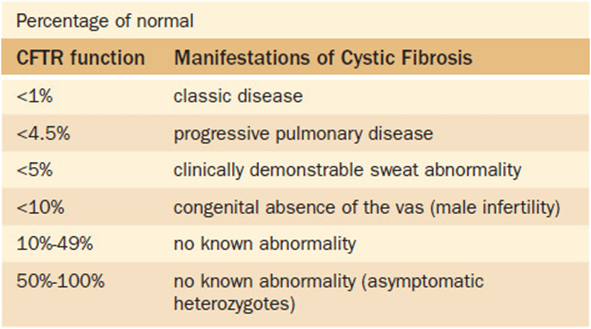

4. There is some predictive correlation between CFTR protein function and clinical symptoms (Table 16-4).

Table 16-4. Relationship Between CFTR Protein Function and Observed Symptoms

5. Although CF does not have locus heterogeneity, there is marked allelic heterogeneity. Over 1000 mutations in the CF gene have been reported to the Cystic Fibrosis Genetic Analysis Consortium as of August 2012.

6. Although there is a large degree of allelic heterogeneity, a single mutation is found in 75% of persons with CF who are of northern European descent. This mutation is a 3-bp deletion in exon 10 that results in a missing phenylalanine amino acid at position 508 of the CFTR protein. This is designated as deltaF508. As was discussed in Chapter 15, it is likely that the high incidence of this mutation is due to a heterozygote advantage with a resistance to cholera deaths.

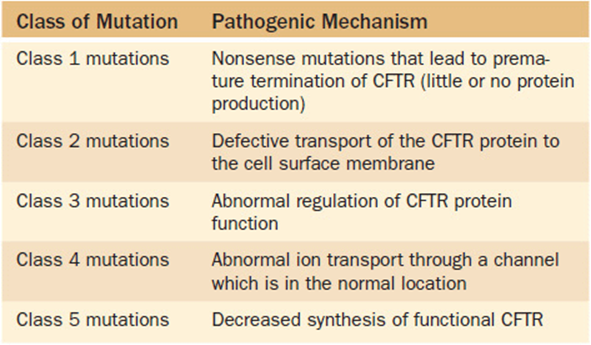

7. There are multiple different pathogenic mechanisms that may cause CF. These have been grouped in five classes of mutations based on the mechanism (Table 16-5).

Table 16-5. Functional Classes of Cystic Fibrosis Mutations

8. Several intragenic variants in the noncoding regions can influence gene expression. A “poly-T” tract in intron 8 affects gene expression by influencing splicing efficiency. Persons with 7T or 9T variants tend to have normal transcription of the CFTR gene. Those with the 5T variant may generate an anomalous protein product. Also, this influence can be further modified by the number of TG repeats in an adjacent region. Individuals with either 12 or 13 TG repeats are more likely to have a disease phenotype than those with only 11 TG repeats.

9. Polymorphisms in other genes may modify CFTR expression and function. One example is the gene for transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGFβ-1). TGFβ-1 is a cytokine with multiple functions that includes roles in immune response, cell differentiation, and healing. Changes in TGFβ-1 have been reported as modifiers of the CF phenotype. Two mutations of the TGFβ-1 gene have been described that are associated with increased levels of the protein. Higher levels of TGFβ1 are associated with a doubling of the risk of worse pulmonary disease in patients with CF. Table 16-6 lists some of the genes known to modify CFTR expression and function.

Table 16-6. Genes reported to Modify CFTR Expression or Function

TGFβ-1

HLA class II antigens

Mannose binding lectin

Alpha(1)-antitrypsin

Alpha(1)-antichymotrypsin

Glutathione-S-transferase

Nitric oxide synthetase type1

TNF-alpha

IL-1 beta

IL-1 Ra

10. As discussed in Chapter 12 (Atypical Modes of Inheritance) a small number of patients with CF are found to have two mutations due to uniparental disomy rather than both parents being heterozygotes for the disorder.

11. Genotype: phenotype relationships have been extensively studied in CF. The best correlation between genotype and phenotype is seen in the context of pancreatic function. In contrast, genotype-phenotype correlation is generally poor for pulmonary disease in CF; other genotypes have been highly associated with a particular feature in males with CF—congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens.

At this point the reader might be thinking, “This seems excessive. Why was all of this minutia discussed?” In our defense, this information was not provided to flood you with a lot of esoteric material. Rather we gave it to you for two key reasons. First it ties together so many of the concepts discussed in all previous chapters. Just look at the list of concepts in these facts, and all that you have now learned. Second, it is meant to highlight just how complicated clinical genetics can be. If this is what is known about a ‘simple’ Mendelian disorder, imagine how much more complicated things could be with other disorders that are beyond Mendelian in their inheritance. Clearly, just identifying all of the A’s, T’s, G’s and C’s of the human genome has not come close to explaining all of the factors in human disease. There will still be a need for clinicians for decades to come!

A Final Thought

Life is a gift. It is also amazingly complex. The molecular events that control development from a fertilized egg to an adult cannot help but cause awe. Yet the human mind and experimental insights yield tools to explore that complexity. Discovery of biological secrets is a testimony to the power of the human mind. Being able to appreciate how much we share with the biology of other organisms is perhaps the mark of our own uniqueness. We know that all people—and all other creatures—share a common biological heritage. All should be valued. Perhaps that is the true goal of life—to understand ourselves and our relationship to others.

A physician’s job is not an easy one. But never forget to look at life from the view of the patient—especially a patient who has inherited a biological challenge that may affect their quality and length of life. Many of the questions that face biomedicine have not yet been answered. Life is still full of puzzles. That leaves us with two gradually converging paths: learning what we can about the intricacies of the genetic control of our structure and function—and then using that knowledge in creative ways to intervene for the benefit of patients. Medicine is both a science and an art. The clinical challenge to a physician may put those two dimensions in stark relief. But they work together.

![]() Board-Format Practice Questions

Board-Format Practice Questions

1. You see a patient with Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (deletion 4p). The parents have spent a lot of time on the internet. They have read that the gene for achondroplasia is in this region. They understand that this means that their child is missing one copy of the achondroplasia gene. Thus they ask you if they should implement the surveillance recommendations for achondroplasia in their child. You would correct in telling them that:

A. Achondroplasia surveillance should be started immediately.

B. The first step to answer their question would be to sequence the achondroplasia gene.

C. It is probably time to start growth hormone therapy to avoid the extreme short stature seen in achondroplasia.

D. Forget looking on the internet for answers, this will only confuse them.

E. The pathogenesis of achondroplasia is not haplo-insufficiency, so they do not need to worry about achondroplasia related issues in their child.

2. If a condition is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The most likely pathogenetic mechanism would be:

A. Haploinsufficiency.

B. Deficiency of the protein product.

C. Protein interference.

D. Protein suicide.

E. Autoregulatory dysfunction.

3. The one-gene, one enzyme hypothesis:

A. is outdated and has no real clinical relevance.

B. is the most common pathogenetic mechanism in human disease.

C. explains some connective tissue disorders.

D. explains some inborn errors of metabolism.

E. explains some homeotic mutants.

4. Potential explanations that mutations in the same gene can produce different phenotypes would include which one of the following:

A. Mutations in different parts of the gene.

B. Genetic heterogeneity.

C. Genetic homogeneity.

D. Homeotic modulation.

E. Gene-gene mutagenesis.

5. All of the following mechanisms might explain autosomal dominant inheritance of a condition EXCEPT:

A. Haploinsufficiency.

B. Gain of function mutation.

C. Protein interference.

D. Protein suicide.

E. Lyonization.

Appendix

Key Genetic Diseases, Disorders, and Syndromes

As we have worked our way through this book we have used clinical examples as much as possible to highlight key points. The examples we used also were selected for their relative importance. However, not all important conditions to know were discussed in this text. (The conditions specifically mentioned in this text are in the highlighted [bold] words in the list below. For the medical student preparing for your boards, we have compiled a list of conditions we deem “key.” We would suggest that you know in detail all the conditions that are bolded. For all others, you should be familiar with the condition and its key features and be able to describe the major genetic mechanism(s) involved in the disease. Of course this list is not comprehensive. It is our “top 125.” There are many other conditions that may appear on your boards. This is, however, our attempt to focus on what we see as some of the conditions to highlight.

Cancer/Neoplasias

Acute lymphocytic leukemia

Ataxia-telangiectasia

Bloom syndrome

Breast cancer

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)—Philadelphia chromosome

Colon cancer

Gardner syndrome/Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

Lynch syndrome/Hereditary non-polypotic colorectal cancer (HNPCC)

Dyskeratosis congenita

Ewing sarcoma

Multiple endocrine neoplasias (MEN)

Neurofibromatosis type 1

Neurofibromatosis type 2

Pancreatic cancer

Prostate cancer

Retinoblastoma

Tuberous sclerosis

von Hippel-Lindau disease

Chromosomal

1q21.1 deletion

22q.11.2 deletion (including DiGeorge syndrome and Shprintzen/velo-cardio-facial syndrome)

47 XXX

47 XYY

Cri-du-chat syndrome (5p-)

Klinefelter syndrome (XXY) and variants

Triploidy

Trisomy 13

Trisomy 18

Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome)

Turner syndrome (monosomy X)

Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (4p-)

Common Disorders (Single Gene or Multifactorial)

Achondroplasia

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

Cystic fibrosis

Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy

Fragile X

Friedrich ataxia

Hearing loss (Connexin 26)

Hemochromatosis (very common genetic disease)

Hemophilia A and B

Hereditary spherocytosis

Huntington disease

Hypophosphatemic rickets

Long QT syndrome

Ehlers Danlos syndrome(s)

Marfan syndrome

Myotonic dystrophy

Neurofibromatosis type 1

Ocular albinism

Osteogenesis imperfecta type I

Polycystic kidney diseases (adult and childhood types)

Spinocerebellar ataxia/olivopontocerebellar atrophy

Thalassemia

Dysmorphology Syndromes/Malformations

Aicardi syndrome

Albright hereditary osteodystrophy

Angelman syndrome

Bardet-Biedel syndrome

CHARGE syndrome

Cleft lip with or without cleft palate

Club foot

Congenital heart disease (know the types associated with common syndromes)

Craniofrontonasal dysplasia

Ectodermal dysplasia

Gorlin syndrome

Holoprosencephaly

Joubert syndrome

Kabuki syndrome

Kartegener syndrome

McCune-Albright syndrome

Noonan syndrome and related RASopathies

Neural tube defects

Prader-Willi syndrome

Pyloric stenosis

Saethre-Chotzen syndrome

Sotos syndrome

VATER association

van der Woude syndrome

Waardenburg syndrome

Williams syndrome

Immune System Disorders

Bruton agammaglobulinemia

Severe combined immune deficiency (SCID)

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome

Inborn Errors of Metabolism

Albinism

Alkaptonuria

Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency

Biotinidase deficiency

Congenital disorders of glycosylation

Fabry

Familial hypercholesterolemia

Fructosemia

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency

Galactosemia

Gaucher disease

Glycogen storage diseases especially Pompe disease

Homocystinuria (and hyper-homocysteinemia)

Hunter syndrome

Hurler syndrome

Isovaleric acidemia

Lesch-Nyhan syndrome

Maple syrup urine disease

Medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency

Menkes disease

Phenylketonuria

Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome

Tay-Sachs disease

Urea cycle defects/hyperammonemia especially ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency)

Wilson disease

Mitochondrial Disorders

Kearns-Sayre syndrome

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)

Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS)

Myoclonic epilepsy and ragged red fibers disease (MERRF)

Neuropathy ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa (NARP)

Polygenic and Multifactorial (Complex) Disorders

Alcoholism

Alzheimer disease

Arthrosclerosis, heart disease, and stroke

Asthma

Autism

Bipolar affective disorder

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

Diabetes

Fetal alcohol syndrome

Fetal hydantoin syndrome

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome)

Hypertension

Schizophrenia