GENERAL PRINCIPLES IN THE APPROACH TO A CANCER PATIENT

There have been enormous advances in our understanding of cancer biology over the past few decades. The novel treatment approaches, including newer targeted agents, immunotherapies, and advancement in supportive care strategies have given rise to increasing optimism in the fight against cancer. Yet a new diagnosis of cancer raises emotional and spiritual issues in a manner that few other diagnoses do, giving the medical oncologist a unique role in caring for the patient. While caring for a cancer patient, it is important to individualize management to his/her needs and disease state. Listening and taking the time to explain terminology, prognosis, and treatment options are key components in the relationship between the oncologist and the patient. Given the oncologist’s knowledge of and experience with the behavior of advanced malignancies, combined with the use of complex medical regimens often lead to the oncologist serving as the primary care physician during active treatment. Oncologists are central in providing palliative care for symptom relief as well as assisting in the role of end-of-life discussions and care. A trusting relationship thus builds between the patient and the treating physician. This chapter provides an overview of this widely expanding field and provides a platform to understand the basics oncology terminologies and approaches. The chapters following this will provide further details in the management of specific cancers and associated clinical conditions.

Definition

Cancer or malignant tumors is defined as an uncontrolled growth of cells with potential for local invasion and distant metastases.

Classification

![]() Classification of tumors in medical oncology is primarily based on site or organ of origin of the malignancy. Tumors are further classified based on the histopathologic characteristics of the tissue of origin. A pathologic diagnosis is one of the most important steps in management of the cancer, along with the identification of the primary site. Improvement in immunohistochemical (IHC) staining techniques has aided in uniform identification and classification of tumors in general. It is important to remember that the individual characteristics and biology of the tumor, their ability to invade and metastasize, and their response to various therapies varies widely across the tumor types.

Classification of tumors in medical oncology is primarily based on site or organ of origin of the malignancy. Tumors are further classified based on the histopathologic characteristics of the tissue of origin. A pathologic diagnosis is one of the most important steps in management of the cancer, along with the identification of the primary site. Improvement in immunohistochemical (IHC) staining techniques has aided in uniform identification and classification of tumors in general. It is important to remember that the individual characteristics and biology of the tumor, their ability to invade and metastasize, and their response to various therapies varies widely across the tumor types.

![]() The two important terminologies used to refer tumor characteristics are stage and grade.

The two important terminologies used to refer tumor characteristics are stage and grade.

![]() Staging describes the extent of the disease in an individual patient. Staging is used for most solid tumors, unlike hematological malignancies. Staging is essential to the oncologist to plan optimal treatment strategies and prognosis discussions. Stage is also the most important predictor of survival. In research studies, staging is used for comparison between cancer trials. The most commonly used staging systems are the TNM classification system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). “T” represents the primary tumor characteristics. “N” represents the presence and extent of nodal sites of the disease. “M” represents metastasis or distant sites of spread. It is recommended that the reader consult an up-to-date staging manual when evaluating a patient because of frequent revisions for each individual malignancy. Clinical staging primarily uses radiographic data to describe the extent of gross disease. Pathologic staging on the other hand provides additional information gained by the pathologist through microscopic examination of the tumor.

Staging describes the extent of the disease in an individual patient. Staging is used for most solid tumors, unlike hematological malignancies. Staging is essential to the oncologist to plan optimal treatment strategies and prognosis discussions. Stage is also the most important predictor of survival. In research studies, staging is used for comparison between cancer trials. The most commonly used staging systems are the TNM classification system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). “T” represents the primary tumor characteristics. “N” represents the presence and extent of nodal sites of the disease. “M” represents metastasis or distant sites of spread. It is recommended that the reader consult an up-to-date staging manual when evaluating a patient because of frequent revisions for each individual malignancy. Clinical staging primarily uses radiographic data to describe the extent of gross disease. Pathologic staging on the other hand provides additional information gained by the pathologist through microscopic examination of the tumor.

![]() The grade of a tumor is a pathologic description of the cellular characteristics of a given malignancy. It is a measure of the degree of anaplasia or deviation of the growth and differentiation characteristics of a cancer from the parental cell type. Thus a low-grade tumor retains many of the characteristics of the originating cell type and they tend to be associated with a less aggressive behavior and more favorable prognosis. A high-grade tumor is characterized by loss of the characteristics of the originating cell type as evidenced by a higher mitotic activity. High grade tumors are often associated with a poorer prognosis, given the more aggressive behavior of the cells.

The grade of a tumor is a pathologic description of the cellular characteristics of a given malignancy. It is a measure of the degree of anaplasia or deviation of the growth and differentiation characteristics of a cancer from the parental cell type. Thus a low-grade tumor retains many of the characteristics of the originating cell type and they tend to be associated with a less aggressive behavior and more favorable prognosis. A high-grade tumor is characterized by loss of the characteristics of the originating cell type as evidenced by a higher mitotic activity. High grade tumors are often associated with a poorer prognosis, given the more aggressive behavior of the cells.

Epidemiology

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States after heart disease. The lifetime risk of developing cancer in the United States is one in two for men and one in three for women. In the United States, the surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) program has been collecting population based data including cancer related data since 1975 and provides an important source of cancer trends in the population.

Terminologies Used in Cancer Epidemiology and Statistics

It is important to make a distinction between cancer incidence and prevalence.

![]() The cancer incidence rate is the number of newly diagnosed cancers in a set population in a finite amount of time. It is usually expressed as number of new cancer diagnoses per 100,000 people in 1 year.

The cancer incidence rate is the number of newly diagnosed cancers in a set population in a finite amount of time. It is usually expressed as number of new cancer diagnoses per 100,000 people in 1 year.

![]() Cancer prevalence is the number or percentage of people alive with a cancer diagnosis on any given date. This includes new cases and existing cases and is therefore a function of incidence and survival. Cancer prevalence cannot differentiate persons with cured cancer from those with active cancer.

Cancer prevalence is the number or percentage of people alive with a cancer diagnosis on any given date. This includes new cases and existing cases and is therefore a function of incidence and survival. Cancer prevalence cannot differentiate persons with cured cancer from those with active cancer.

![]() Cancer mortality rate as expected is the number of cancer related deaths, in a specified population over a defined period of time.

Cancer mortality rate as expected is the number of cancer related deaths, in a specified population over a defined period of time.

![]() Survival is described in three broad terms: relative 5-year survival, median survival, and overall survival. These statistics are based on observational studies.

Survival is described in three broad terms: relative 5-year survival, median survival, and overall survival. These statistics are based on observational studies.

![]() Relative 5-year survival rates compare the survival among cancer patients with survival among the general population matched in age, gender, and race, adjusted for comorbidities. This statistic method is used in monitoring the progress of cancer detection and treatment in the population.

Relative 5-year survival rates compare the survival among cancer patients with survival among the general population matched in age, gender, and race, adjusted for comorbidities. This statistic method is used in monitoring the progress of cancer detection and treatment in the population.

![]() Overall survival is the percentage of people in a study or treatment group who are alive for a specific period of time, usually 5 years, after being diagnosed with or treated for a cancer. This is also referred to as the cancer survival rate.

Overall survival is the percentage of people in a study or treatment group who are alive for a specific period of time, usually 5 years, after being diagnosed with or treated for a cancer. This is also referred to as the cancer survival rate.

![]() The median survival is more indicative of prognosis and is the statistic that is most commonly quoted to cancer patients. According to the National Cancer Institute, median survival is the time from diagnosis or treatment at which half of the patients with a given disease are found to be alive. In a clinical trial, the median survival time is one way to measure the effectiveness of a given treatment.

The median survival is more indicative of prognosis and is the statistic that is most commonly quoted to cancer patients. According to the National Cancer Institute, median survival is the time from diagnosis or treatment at which half of the patients with a given disease are found to be alive. In a clinical trial, the median survival time is one way to measure the effectiveness of a given treatment.

![]() Progression-free survival is another terminology that is often used in clinical studies, which refer to the duration of time during and after treatment when the cancer has not worsened in a patient.

Progression-free survival is another terminology that is often used in clinical studies, which refer to the duration of time during and after treatment when the cancer has not worsened in a patient.

Epidemiologic Factors

The risk of developing cancer is affected by important demographic and geographic factors in addition to other specific risk factors associated with individual cancers.

![]() Age is both an important epidemiologic factor and a risk factor. The highest incidence of certain cancers varies with age, for example, acute lymphoblastic lymphoma and neuroblastomas have their highest incidence in young children, while testicular cancers and Hodgkin’s lymphoma have their peak incidence in young adulthood. On the other hand, the risk of common adult cancers increases with age, likely from combination of accumulating effects of environmental carcinogens and internal factors such as genetic mutations, hormonal influences and immune system impairments.

Age is both an important epidemiologic factor and a risk factor. The highest incidence of certain cancers varies with age, for example, acute lymphoblastic lymphoma and neuroblastomas have their highest incidence in young children, while testicular cancers and Hodgkin’s lymphoma have their peak incidence in young adulthood. On the other hand, the risk of common adult cancers increases with age, likely from combination of accumulating effects of environmental carcinogens and internal factors such as genetic mutations, hormonal influences and immune system impairments.

![]() Cancer affects both sexes with some cancers being gender specific. While overall incidence of cancer is higher in men than women, the gender distribution of individual cancers varies.

Cancer affects both sexes with some cancers being gender specific. While overall incidence of cancer is higher in men than women, the gender distribution of individual cancers varies.

![]() Race and ethnicity are other important epidemiologic factors that influence both cancer incidence and death rates. Although it is not completely understood at this time, it is possibly related to interaction of the genetic and biologic characteristics of the individual patient with environmental factors such as exposure to certain dietary products or infectious agents.

Race and ethnicity are other important epidemiologic factors that influence both cancer incidence and death rates. Although it is not completely understood at this time, it is possibly related to interaction of the genetic and biologic characteristics of the individual patient with environmental factors such as exposure to certain dietary products or infectious agents.

![]() Socioeconomic factors such as lack of education and unemployment also plays a very intricate role with the above factor. Societies with lower socioeconomic status are at a higher risk that is attributable to inadequate use of screening tests, high-risk behavior such as alcohol use and smoking, and delays in seeking medical attention.

Socioeconomic factors such as lack of education and unemployment also plays a very intricate role with the above factor. Societies with lower socioeconomic status are at a higher risk that is attributable to inadequate use of screening tests, high-risk behavior such as alcohol use and smoking, and delays in seeking medical attention.

![]() Geographic location influences certain cancers primarily from the environmental exposure to certain carcinogens and indirectly by the socioeconomic status and racial and ethnic background of its population composition.

Geographic location influences certain cancers primarily from the environmental exposure to certain carcinogens and indirectly by the socioeconomic status and racial and ethnic background of its population composition.

Cancer Statistics

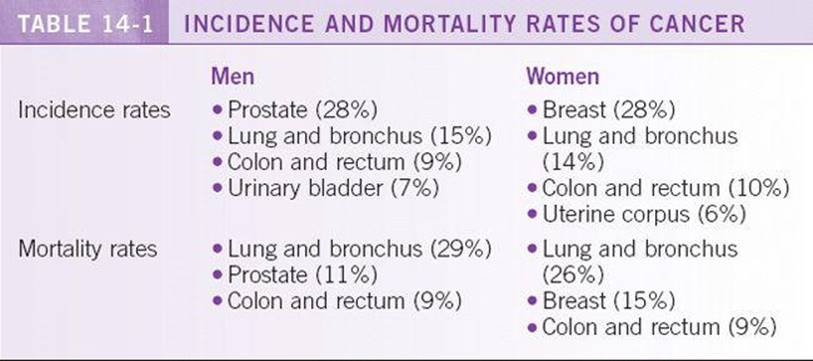

According to American Cancer Society, a total of 1,529,560 new cancer cases and 569,490 deaths from cancer are projected to occur in the United States in 2010. Overall cancer incidence rates decreased in the most recent period in both men (1.3% per year from 2000 to 2006) and women (0.5% per year from 1998 to 2006). There was also noted decrease in the death rates in both sexes. Among men, death rates for all races combined decreased by 21% between 1990 and 2006. Among women, the overall cancer death rates between 1991 and 2006 decreased by 12.3%. The reduction in the overall cancer death rates translates to the avoidance of approximately 767,000 deaths from cancer over the 16-year period. See Table 14-1 for the gender specific cancer incidence and mortality rates. 1

Pathophysiology

Few concepts in medicine are as complex as the pathophysiology of cancer. Chapter 15 deals with the molecular basis of carcinogenesis.

Risk Factors

Certain risk factors have been associated with specific cancers, such as tobacco use in lung and head and neck cancers, cytotoxic therapy with secondary hematological malignancies, HPV infection and risk of cervical dysplasia and head and neck cancers. There is however still several unknown risk factors that contributes to the natural history of cancer. The individual risk factors for specific cancers are elucidated in the remaining chapters.

DIAGNOSIS

Common Clinical Presentation

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy may cause a patient to seek medical attention, may be found incidentally on physical examination, or found by imaging. The differential diagnosis is broad, including infectious etiologies, autoimmune diseases, sarcoidosis, drug hypersensitivity, benign or clonal lymphoproliferative disorders, and malignancy. Malignant causes of lymphadenopathy include lymphoma and metastatic solid tumors. Features that suggest a malignant etiology of lymphadenopathy include lymph nodes >2 cm in size, lymph nodes that are hard or fixed to adjacent structures, and supraclavicular or epitrochlear lymphadenopathy. Lymphadenopathy may be localized or generalized, and the differential diagnosis varies depending on the location and distribution of the enlarged lymph nodes. When biopsy is indicated, an open biopsy is preferred over a core biopsy or aspiration as it allows for evaluation of the lymph node architecture, which is often necessary for classification of lymphoma.2

Brain Mass

![]() The differential diagnosis for a brain mass includes metastatic disease, primary brain tumors, CNS lymphoma, hamartoma, AV malformation, demyelination, cerebral infarction or bleeding, and infection.

The differential diagnosis for a brain mass includes metastatic disease, primary brain tumors, CNS lymphoma, hamartoma, AV malformation, demyelination, cerebral infarction or bleeding, and infection.

![]() Brain metastases are the most common intracranial tumors in adults, accounting for 50% of all brain tumors. The presence of blood-brain barrier prevents penetration of chemotherapeutic agents into the CNS, thus providing a sanctuary site for metastatic tumor cells. The incidence of brain metastases is increasing, perhaps due to the increasing sensitivity of MRI. Lung, kidney, colorectal, and breast carcinomas and melanoma frequently metastasize to the brain. Cancer of the prostate, esophagus, oropharynx and nonmelanoma skin cancers rarely metastasize to the brain.

Brain metastases are the most common intracranial tumors in adults, accounting for 50% of all brain tumors. The presence of blood-brain barrier prevents penetration of chemotherapeutic agents into the CNS, thus providing a sanctuary site for metastatic tumor cells. The incidence of brain metastases is increasing, perhaps due to the increasing sensitivity of MRI. Lung, kidney, colorectal, and breast carcinomas and melanoma frequently metastasize to the brain. Cancer of the prostate, esophagus, oropharynx and nonmelanoma skin cancers rarely metastasize to the brain.

![]() Signs and symptoms of a brain mass include headache, focal neurological deficits, altered mental status, seizures, and stroke.

Signs and symptoms of a brain mass include headache, focal neurological deficits, altered mental status, seizures, and stroke.

![]() The imaging study of choice is a contrast-enhanced MRI, which will delineate the location, presence of other lesions, margins of the lesion, and presence of vasogenic edema. Brain metastases are usually located in the gray and white matter junction and have a large amount of vasogenic edema.

The imaging study of choice is a contrast-enhanced MRI, which will delineate the location, presence of other lesions, margins of the lesion, and presence of vasogenic edema. Brain metastases are usually located in the gray and white matter junction and have a large amount of vasogenic edema.

![]() A brain biopsy should be preformed whenever the diagnosis is in doubt. This is particularly important in patients who have a single lesion or have a cancer that rarely metastasizes to the brain. Often, a brain lesion is the primary presentation of a malignancy. Evaluation for a source of a metastatic focus, particularly lung and breast cancer, should precede biopsy.

A brain biopsy should be preformed whenever the diagnosis is in doubt. This is particularly important in patients who have a single lesion or have a cancer that rarely metastasizes to the brain. Often, a brain lesion is the primary presentation of a malignancy. Evaluation for a source of a metastatic focus, particularly lung and breast cancer, should precede biopsy.

![]() Basic initial workup includes staging CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, colonoscopy, comprehensive skin exam, and mammogram.

Basic initial workup includes staging CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, colonoscopy, comprehensive skin exam, and mammogram.

Liver Metastases

![]() The differential diagnosis of a focal liver lesion includes primary malignant liver tumors (such as hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma), metastatic liver lesions, benign hepatic cysts, cavernous hemangioma, hepatic adenoma, and abscesses.

The differential diagnosis of a focal liver lesion includes primary malignant liver tumors (such as hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, lymphoma, and sarcoma), metastatic liver lesions, benign hepatic cysts, cavernous hemangioma, hepatic adenoma, and abscesses.

![]() Before proceeding to diagnostic testing, it is important to assess the clinical scenario. For example, is this an incidental finding? Does the patient have any risk factors such as hepatitis C/cirrhosis, oral contraceptive use, travel history, history of malignancy, or constitutional symptoms?

Before proceeding to diagnostic testing, it is important to assess the clinical scenario. For example, is this an incidental finding? Does the patient have any risk factors such as hepatitis C/cirrhosis, oral contraceptive use, travel history, history of malignancy, or constitutional symptoms?

![]() Diagnostic modalities include liver ultrasound, triphasic CT of the liver, and MRI of the liver. If there is a likelihood of malignancy, a fine-needle biopsy can be done. It is important to note that if a patient has a remote history of cancer, one cannot assume that a new liver lesion is due to metastases. A new liver lesion has to be definitively diagnosed, as a second unrelated malignancy cannot be ruled out.

Diagnostic modalities include liver ultrasound, triphasic CT of the liver, and MRI of the liver. If there is a likelihood of malignancy, a fine-needle biopsy can be done. It is important to note that if a patient has a remote history of cancer, one cannot assume that a new liver lesion is due to metastases. A new liver lesion has to be definitively diagnosed, as a second unrelated malignancy cannot be ruled out.

Bone Lesions

![]() Bone lesions can be the initial presentation of metastatic cancer or can present later in advanced malignancy. Bone metastases are commonly due to multiple myeloma, breast cancer, or prostate cancer, but almost any solid malignancy can metastasize to the bone. They are classified as osteolytic or osteoblastic lesions. Osteolytic lesions refer to the destruction of normal bone, whereas osteoblastic lesions are the result of deposition of new bone. Multiple myeloma lesions are purely osteolytic. Metastases from prostate cancer are usually osteoblastic. Breast cancer metastases are usually a combination of both. Bone is a preferential site for metastasis because tumor cells express and produce various chemokines and adhesive molecules that bind corresponding molecules on the stromal cells of the bone. For example, expression of RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand) in bone facilitates development of metastasis by binding RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B) on the surface of tumor cells. Also, tumor cells can express bone sialoprotein and bind collagen type I in the extracellular matrix in the bone, thus becoming more adhesive.

Bone lesions can be the initial presentation of metastatic cancer or can present later in advanced malignancy. Bone metastases are commonly due to multiple myeloma, breast cancer, or prostate cancer, but almost any solid malignancy can metastasize to the bone. They are classified as osteolytic or osteoblastic lesions. Osteolytic lesions refer to the destruction of normal bone, whereas osteoblastic lesions are the result of deposition of new bone. Multiple myeloma lesions are purely osteolytic. Metastases from prostate cancer are usually osteoblastic. Breast cancer metastases are usually a combination of both. Bone is a preferential site for metastasis because tumor cells express and produce various chemokines and adhesive molecules that bind corresponding molecules on the stromal cells of the bone. For example, expression of RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand) in bone facilitates development of metastasis by binding RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B) on the surface of tumor cells. Also, tumor cells can express bone sialoprotein and bind collagen type I in the extracellular matrix in the bone, thus becoming more adhesive.

![]() Signs and symptoms of bone involvement include focal pain, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, and cord compression.

Signs and symptoms of bone involvement include focal pain, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, and cord compression.

![]() Diagnosis is usually made by radiological testing, including plain films, which diagnose osteolytic lesions, and bone scans, which detect osteoblastic lesions only.

Diagnosis is usually made by radiological testing, including plain films, which diagnose osteolytic lesions, and bone scans, which detect osteoblastic lesions only.

![]() Treatment includes systemic chemotherapy and hormone therapy. Local radiation can be used to palliate symptoms and prevent pathological fractures. Bisphosphonates are used to treat hypercalcemia, treat bone pain, prevent fractures, and prevent further destruction of the normal bone.

Treatment includes systemic chemotherapy and hormone therapy. Local radiation can be used to palliate symptoms and prevent pathological fractures. Bisphosphonates are used to treat hypercalcemia, treat bone pain, prevent fractures, and prevent further destruction of the normal bone.

History

The importance of a thorough history taking cannot be stressed enough. The duration of symptoms can provide some insight into the aggressiveness of the malignancy. The associated symptom complex can provide information on the extent of the disease, especially organ specific symptoms which can point toward metastatic involvement by the disease. For example, new onset neurologic symptoms in a lung cancer patient should prompt imaging of the head. In a patient with metastatic disease, it may be important to first address the most bothersome symptom(s) for the purpose of palliation before starting definitive treatment for the cancer. Assessment of nutritional status and weight changes is an integral part of cancer management. Performance scales as mentioned below are used to assess the functional status of the patient either before starting treatment or during ongoing treatment. While evaluating a patient on active treatment, it is important for the treating physician to first familiarize with the most common side effects of that treatment in order to dose adjust or change treatment if necessary.

Evaluation of Performance Status

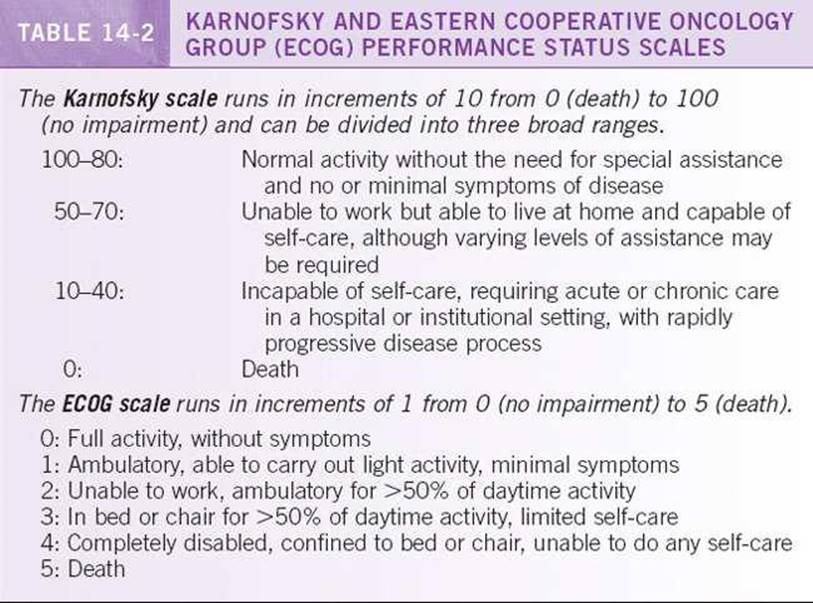

Performance status describes the functional abilities of the oncology patient. It is frequently used to provide a standardized assessment of patients considered for inclusion in protocols or to characterize patients at diagnosis or during treatment or follow-up. The initial performance status score predicts survival. The Karnofsky Performance Status and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scale (Table 14-2) are two of the most frequently used scales.

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination is warranted in any newly diagnosed cancer patient with particular attention to the organ involved. In metastatic cancers where the primary site is not yet identified, a physical examination may provide the first clue as to the diagnosis. This should include a breast and pelvic examination in women, a genital examination in men, and rectal examination in both men and women. In other instances, a good physical examination may provide clue as to the extent of the primary malignancy. They may also point toward metastatic spread of tumors, for example enlargement of the liver in a patient with colon cancer or bone tenderness in a breast cancer patient. A good physical examination can also aid in following response to treatment, such as the decreasing size of the breast mass or lymph nodes.

Diagnostic Testing

Pathology Diagnosis

The treatment of a malignancy requires a diagnosis based on tissue pathology. In only rare emergent situations is treatment started without a diagnosis. Consultation from the surgical, medical, and radiation oncology team members is essential. These oncology professionals are crucial to include in cases in which prompt therapy should be delivered to the patient to reduce the risk of morbidity or mortality in certain oncologic emergencies.

![]() Light microscopy is central to diagnosis. It delineates the microscopic structure of the malignancy, such as nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio in leukemia, invasion into the microvasculature, or extent of glandular crowding in adenocarcinoma. Additional studies, including immunohistochemical staining, flow cytometry, cytogenetics, and molecular studies for gene rearrangements can corroborate a suspected diagnosis and assist in further subclassification.

Light microscopy is central to diagnosis. It delineates the microscopic structure of the malignancy, such as nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio in leukemia, invasion into the microvasculature, or extent of glandular crowding in adenocarcinoma. Additional studies, including immunohistochemical staining, flow cytometry, cytogenetics, and molecular studies for gene rearrangements can corroborate a suspected diagnosis and assist in further subclassification.

![]() Immunohistochemical staining identifies specific proteins in the tissue based on the principle of antigen-antibody complex. The development of fluorescent and nonfluorescent chromogens along with various amplification techniques has increased the sensitivity and specificity of this procedure. This technique is widely used in surgical pathology for typing tumors based on the principle of differential expression of proteins in different biologic tissues. They help provide such fundamental information as: is this a tumor? Is it benign or malignant? What type of tumor is it? They also provide information on the tissue of origin of the tumor. For example, cytokeratin stains are used to identify carcinomas from sarcomas, CD20 for B-cell lymphoma, etc. Others provide prognostic information such as Ki67, which is a marker of proliferation.

Immunohistochemical staining identifies specific proteins in the tissue based on the principle of antigen-antibody complex. The development of fluorescent and nonfluorescent chromogens along with various amplification techniques has increased the sensitivity and specificity of this procedure. This technique is widely used in surgical pathology for typing tumors based on the principle of differential expression of proteins in different biologic tissues. They help provide such fundamental information as: is this a tumor? Is it benign or malignant? What type of tumor is it? They also provide information on the tissue of origin of the tumor. For example, cytokeratin stains are used to identify carcinomas from sarcomas, CD20 for B-cell lymphoma, etc. Others provide prognostic information such as Ki67, which is a marker of proliferation.

![]() Flow cytometry characterizes and sorts individual cells suspended in liquid as they flow in a narrow stream that pass through a beam of laser light. It is most frequently applied in hematologic malignancies where certain antigen profiles are diagnostic (e.g., CD5/CD23 coexpression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia). In cytogenetic testing, chromosomes from blood, bone marrow, or solid tissue can be isolated to identify deletions, translocations, trisomies, or insertions into the genome. In this process, chromosomes of 20 cells are counted in metaphase. The bands within the chromosomes are studied to identify any of the aforementioned abnormalities. Cytogenetic testing has been taken one step further with the advent of FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization). The cellular DNA from the biopsy specimen prepared on glass and mixed with a known DNA probes that are fluorescently labeled, such as 9;22 rearrangement for chronic myeloid leukemia. If the DNA contains that translocation, the probe light up under fluorescent microscopy will align differently than if the translocation is not present. The advantage of this test is that it can identify subtle changes in the chromosome. However, it can only identify one abnormality at a time (unlike cytogenetic testing) so the investigator must know which abnormality to look for.

Flow cytometry characterizes and sorts individual cells suspended in liquid as they flow in a narrow stream that pass through a beam of laser light. It is most frequently applied in hematologic malignancies where certain antigen profiles are diagnostic (e.g., CD5/CD23 coexpression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia). In cytogenetic testing, chromosomes from blood, bone marrow, or solid tissue can be isolated to identify deletions, translocations, trisomies, or insertions into the genome. In this process, chromosomes of 20 cells are counted in metaphase. The bands within the chromosomes are studied to identify any of the aforementioned abnormalities. Cytogenetic testing has been taken one step further with the advent of FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization). The cellular DNA from the biopsy specimen prepared on glass and mixed with a known DNA probes that are fluorescently labeled, such as 9;22 rearrangement for chronic myeloid leukemia. If the DNA contains that translocation, the probe light up under fluorescent microscopy will align differently than if the translocation is not present. The advantage of this test is that it can identify subtle changes in the chromosome. However, it can only identify one abnormality at a time (unlike cytogenetic testing) so the investigator must know which abnormality to look for.

Laboratory Testing

Routine evaluation with complete blood counts and a comprehensive metabolic panel is important for baseline information about organ function. Any abnormal laboratory data may provide additional information on organ infiltration by the tumor, for example, an elevated alkaline phosphatase may provide indication on bony metastasis, transaminitis may be indicative of liver involvement, and low blood counts may point toward bone marrow infiltration. Tumor markers may provide additional information in some cases. Tumor markers are useful in diagnostic workup of certain germ cell tumors, such as testicular and neuroendocrine tumors. The majority of tumor markers, however, lack sensitivity and specificity for cancer diagnosis. Some tests may provide prognostic information as they reflect tumor burden, such as an LDH in lymphoma, and LDH, HCG, and AFP in testicular germ cell tumors. Most tumor markers are used in clinical practice for the purpose of monitoring treatment response and progression of cancer. The only tumor marker that is part of screening in the United States is prostate-specific antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer, which is now controversial.

Imaging Modalities3

![]() CT (computed tomography) allows cross-sectional imaging of the patient. Additional applications of CT include three-dimensional reconstructions and CT angiography. Intravenous radiocontrast medium is frequently utilized to enhance the sensitivity of the imaging. Risks of radiocontrast media include allergic reaction and nephrotoxicity.

CT (computed tomography) allows cross-sectional imaging of the patient. Additional applications of CT include three-dimensional reconstructions and CT angiography. Intravenous radiocontrast medium is frequently utilized to enhance the sensitivity of the imaging. Risks of radiocontrast media include allergic reaction and nephrotoxicity.

![]() MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is widely used in imaging the brain for either primary CNS tumors or metastases. MRI also has an emerging role in evaluation of breast cancer with breast MRI. MRI of the liver has a role in hepatocellular carcinoma as well as evaluation of solitary liver metastases in colon cancer. Absolute contraindications to MRI scanning include pacemakers, aneurysm clips, certain metallic cardiac prosthetic valves, and intraocular metal fragments.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is widely used in imaging the brain for either primary CNS tumors or metastases. MRI also has an emerging role in evaluation of breast cancer with breast MRI. MRI of the liver has a role in hepatocellular carcinoma as well as evaluation of solitary liver metastases in colon cancer. Absolute contraindications to MRI scanning include pacemakers, aneurysm clips, certain metallic cardiac prosthetic valves, and intraocular metal fragments.

![]() PET (positron emission tomography) is a functional imaging modality that images the distribution of intravenously administered radiolabeled tracers. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is the most widely utilized metabolic tracer. PET is most sensitive in aggressive and metabolically active tumors such as melanoma, head and neck, breast, lung, esophageal, cervical, and colorectal cancer, as well as aggressive subtypes of lymphoma. FDG-PET has a lower sensitivity in slower-growing tumors such as low-grade lymphomas, neuroendocrine tumors, and bronchioalveolar cell lung carcinoma. PET scans can be performed with concurrent CT (PET-CT) to merge both functional and anatomic imaging.

PET (positron emission tomography) is a functional imaging modality that images the distribution of intravenously administered radiolabeled tracers. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is the most widely utilized metabolic tracer. PET is most sensitive in aggressive and metabolically active tumors such as melanoma, head and neck, breast, lung, esophageal, cervical, and colorectal cancer, as well as aggressive subtypes of lymphoma. FDG-PET has a lower sensitivity in slower-growing tumors such as low-grade lymphomas, neuroendocrine tumors, and bronchioalveolar cell lung carcinoma. PET scans can be performed with concurrent CT (PET-CT) to merge both functional and anatomic imaging.

![]() Radionuclide bone scans are frequently used to detect bone metastases. They are less sensitive to purely osteolytic lesions, such as in multiple myeloma.

Radionuclide bone scans are frequently used to detect bone metastases. They are less sensitive to purely osteolytic lesions, such as in multiple myeloma.

![]() Skeletal survey includes plain x-rays of the skull, spine, pelvis, and extremities. It is utilized in multiple myeloma to survey for osteolytic bone lesions.

Skeletal survey includes plain x-rays of the skull, spine, pelvis, and extremities. It is utilized in multiple myeloma to survey for osteolytic bone lesions.

Utilization of other forms of medical imaging including volumetric (3D) anatomical imaging, dynamic contrast imaging and functional (molecular) imaging are in the process of being tested and validated in clinical trials. If successful, the use of medical imaging may serve as surrogate endpoint in clinical trials and aid clinicians in making earlier treatment decisions.

Diagnostic Procedures

An array of diagnostic procedures is available to establish a cancer diagnosis in a given patient. This may range from simple blood tests or bone marrow biopsies obtained by the treating physician in hematological malignancies to a multispecialty approach. Tissue for pathologic evaluation can be obtained by surgical approaches, such as lymph node biopsy or surgical resection specimen. Image guided such as CT or USG guided biopsy of target lesion is gaining popularity, as they are less invasive. Evaluations of luminal tumors are aided by the use of various endoscopic procedures. Some clinical situations may, however, pose special clinical challenges requiring more than one attempt and involvement of more than one specialty. Other diagnostic procedures such as lumbar puncture, pleural fluid thoracentesis or ascitic fluid paracentesis are done as part of diagnostic workup or for palliation of symptoms. Other sophisticated techniques such as chemo-embolization are discussed in relevant chapters.

TREATMENT

Approach to Oncology Treatment

The majority of adult solid malignancies are best managed through a multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists. There are often multiple different treatment options, and patients should be an active part of the decision-making process. An important element in the treatment of cancer patients is to define the goals of treatment, addressing the possibilities of cure, prolongation of survival, or improvement in quality of life in individual cases. Treatment recommendations should be carefully tailored to the individual patient, taking into account comorbid conditions, performance status, and other psychosocial issues.

Principles of Surgical Approach in Cancer

Surgery still remains the most effective modality for curing cancer confined to a local site. In many instances, the surgical removal of the primary cancer also involves the removal of a regional lymph node area. Appropriate patients can be identified for definitive or curative surgery. The goal is for the surgeon to remove all neoplastic cells, including the resection of a complete margin of normal tissue around the primary tumor. Depending on the primary tumor, patients with a solitary or limited number of metastases to sites such as the brain, liver, and lung can be cured by the surgical resection of the metastatic disease. Cytoreductive surgery or tumor debulking can facilitate subsequent radiation and/or chemotherapy in some malignancies such as ovarian cancer. Surgery may also be necessary in the palliative setting to relieve symptoms, such as intestinal obstruction from colon cancer.

Principles of Radiation Therapy

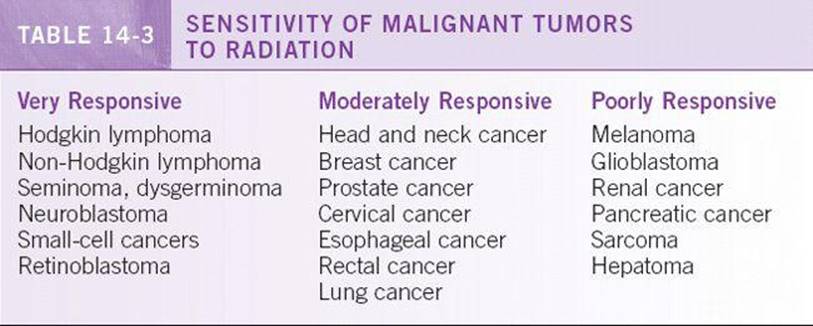

Radiation therapy is the treatment of choice for some cancers. The use of this treatment modality is based on the responsiveness of the cancer to ionizing radiation. Some cancers are extremely sensitive, including lymphomas and seminomas, whereas others are relatively resistant. Radiation therapy can be the sole curative local modality in malignancies such as cervical cancer and prostate cancer. It is also useful in the adjuvant setting to increase the likelihood of local or regional control after surgery. Radiation therapy also plays a key role in the palliation of symptoms from primary or metastatic tumor masses, including spinal cord compression and bone metastases. Further details of the principles and uses of radiation therapy are elucidated in Chapter 17. See Table 14-3 for list of radiosensitive tumors.

Principles of Systemic Therapy

In contrast to surgery or radiation therapy, which has only local effects on the tumor, the role of systemic therapy is geared at treating both the local tumor and potential or actual areas of metastatic disease throughout the body. Systemic therapy for treatment of cancers refers to traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, immunotherapy and newer targeted therapy. The uses of different systemic therapy in various cancers and the side effects are discussed in subsequent chapters. Clinical trials are important tools in medical oncology to test novel treatment approaches in the management of cancer. Important clinical trials in the past decade have paved the way for more effective and less toxic regimens. Trials have also added multiple new agents and important biologic information in the fight against cancer. It is important to screen the individual patient for eligibility for the clinical trials available at your institution.

Chemotherapy

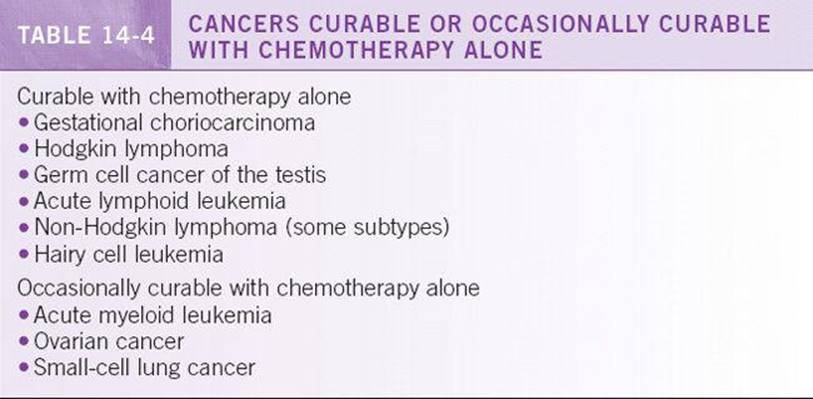

Before the initiation of chemotherapy, the goal of treatment must be clearly defined and discussed with the patient. Not all patients are candidates for chemotherapy. Potential risks and benefits must be considered when deciding to treat a patient with cytotoxic agents. The performance status and overall nutritional state of the cancer patient is extremely important when making the decision to use chemotherapy. Patients with performance status scores of 3 to 4 on the ECOG scale are usually not candidates for systemic therapy unless they have previously untreated tumors known to be especially responsive to chemotherapy. See Table 14-4 for list of chemosensitive tumors.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy refers to the use of pharmacologic agents that are intrinsic to the immune system. High concentrations of these biologic response modifiers stimulate the immune system to kill cancer cells. Examples include interferon-alpha, interleukin-2, and monoclonal antibodies. Toxicities can range from fevers and flulike symptoms to anaphylaxis and adult respiratory distress syndrome–like manifestations. Development of tumor vaccines and other potent immunotherapies are gaining momentum with increasing understanding of cancer immunology.

Targeted Therapies

These therapies interfere with specific pathways needed for the growth and survival of cancer cells. These therapies may include monoclonal antibodies or small molecule inhibitors, which target specific receptors or kinases such as the epidermal growth factors receptor, the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase. The past decade has seen the approval of several targeted agents in the treatment of various cancers either as single agent or in combination with chemotherapy. Endocrine therapies used in the treatment of prostate and breast cancer are among the oldest form of targeted agents. They are very effective treatment strategies in these hormone sensitive cancers and used widely in multiple clinical settings.

Systemic chemotherapy has been used in various clinical settings.

![]() Adjuvant therapy refers to the use of systemic therapy following complete surgical resection to improve both disease-free and overall survival. The goal is to eliminate undetected local and micrometastatic foci of tumor. There is no way to measure or follow response to therapy, and thus duration of treatment is determined empirically by clinical trials. Cancers for which adjuvant chemotherapy has proved to benefit survival include colorectal, breast, lung, ovarian cancers, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Similarly, adjuvant hormonal therapy is effective in improving survival in breast cancer patients who are estrogen receptor positive.

Adjuvant therapy refers to the use of systemic therapy following complete surgical resection to improve both disease-free and overall survival. The goal is to eliminate undetected local and micrometastatic foci of tumor. There is no way to measure or follow response to therapy, and thus duration of treatment is determined empirically by clinical trials. Cancers for which adjuvant chemotherapy has proved to benefit survival include colorectal, breast, lung, ovarian cancers, rhabdomyosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. Similarly, adjuvant hormonal therapy is effective in improving survival in breast cancer patients who are estrogen receptor positive.

![]() Neoadjuvant therapy refers to systemic therapy that is administered before surgery. The goal of neoadjuvant therapy is to decrease the tumor burden for the definitive surgical procedure, thus minimizing complications and making organ preservation more feasible. In addition, the clinician can monitor the tumor responsiveness to the systemic agent and able to deliver systemic treatment without delay to eliminate micrometastatic disease. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is used in breast, esophageal, rectal, lung, and bladder cancers, as well some sarcomas.

Neoadjuvant therapy refers to systemic therapy that is administered before surgery. The goal of neoadjuvant therapy is to decrease the tumor burden for the definitive surgical procedure, thus minimizing complications and making organ preservation more feasible. In addition, the clinician can monitor the tumor responsiveness to the systemic agent and able to deliver systemic treatment without delay to eliminate micrometastatic disease. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is used in breast, esophageal, rectal, lung, and bladder cancers, as well some sarcomas.

![]() Combined modality therapy refers to the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy used to treat bulky disease, especially when curative resection is not possible or less effective or when organ preservation is considered. For example, combination therapy can be curative and organ preserving in certain tumors such as laryngeal and anal cancers. Combined modality therapy improves survival for some patients with locally advanced lung, esophageal, head and neck, pancreatic, and cervical cancers. The combined modality therapy can also be used to decrease the size of the tumor for either a curative or a salvage surgical procedure later.

Combined modality therapy refers to the combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy used to treat bulky disease, especially when curative resection is not possible or less effective or when organ preservation is considered. For example, combination therapy can be curative and organ preserving in certain tumors such as laryngeal and anal cancers. Combined modality therapy improves survival for some patients with locally advanced lung, esophageal, head and neck, pancreatic, and cervical cancers. The combined modality therapy can also be used to decrease the size of the tumor for either a curative or a salvage surgical procedure later.

![]() Palliative chemotherapy is typically administered in metastatic setting or advanced stage of malignancy. This treatment modality is not intended for cure, but for slowing progression of disease and prolongs life. The chemotherapy agents are either administered as combination or single agents sequentially in this setting.

Palliative chemotherapy is typically administered in metastatic setting or advanced stage of malignancy. This treatment modality is not intended for cure, but for slowing progression of disease and prolongs life. The chemotherapy agents are either administered as combination or single agents sequentially in this setting.

![]() Induction chemotherapy is used as the initial treatment of a malignancy to achieve complete remission or significant cytoreduction. It is commonly used in the treatment of acute leukemia and lymphoma. Consolidation chemotherapy is given after a patient is in remission to prolong the duration of remission and overall survival in patients with acute leukemia. Maintenance chemotherapy is the use of prolonged, low-dose chemotherapy to prolong the duration of remission and achieve a cure in those patients; it is currently only utilized in certain leukemias. Salvage chemotherapy is given with the intent to control disease or palliate symptoms after the failure of initial treatments.

Induction chemotherapy is used as the initial treatment of a malignancy to achieve complete remission or significant cytoreduction. It is commonly used in the treatment of acute leukemia and lymphoma. Consolidation chemotherapy is given after a patient is in remission to prolong the duration of remission and overall survival in patients with acute leukemia. Maintenance chemotherapy is the use of prolonged, low-dose chemotherapy to prolong the duration of remission and achieve a cure in those patients; it is currently only utilized in certain leukemias. Salvage chemotherapy is given with the intent to control disease or palliate symptoms after the failure of initial treatments.

![]() High-dose chemotherapy is typically used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. High doses of chemotherapy are used to ablate the bone marrow requiring rescue with allogeneic or autologousbone marrow or stem cell replacement to repopulate the marrow. Allogeneic transplants have been curative in selected patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia and acute leukemias. Autologous stem cell transplants have been most successful for aggressive lymphomas and multiple myeloma. The use of bone marrow transplant in solid organ malignancies remains controversial.

High-dose chemotherapy is typically used in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. High doses of chemotherapy are used to ablate the bone marrow requiring rescue with allogeneic or autologousbone marrow or stem cell replacement to repopulate the marrow. Allogeneic transplants have been curative in selected patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia and acute leukemias. Autologous stem cell transplants have been most successful for aggressive lymphomas and multiple myeloma. The use of bone marrow transplant in solid organ malignancies remains controversial.

MONITORING/FOLLOW-UP

Response to Therapy

In general, responses to therapy are measured by objective changes in tumor size and increases in disease-free and overall survival. The RECIST (response criteria in solid tumors) is a widely utilized tool for describing changes in solid tumor size in response to therapy. RECIST criteria are a voluntary, international standard that is not an NCI standard. They are based on a simplification of former methods (WHO, ECOG) and based on measurable disease.4Other response criteria are utilized in hematologic malignancies. The single most important indicator of the effectiveness of chemotherapy is the complete response rate. No patient with advanced cancer can be cured without attaining a complete remission. There are frequent changes in the definitions of response criteria assessment. The reader is advised to look for updated guidelines in this regard. The present information is currently available and defined on the NCI website.5

![]() Complete response is defined as the disappearance of all target lesions on imaging studies of at least one month of duration.

Complete response is defined as the disappearance of all target lesions on imaging studies of at least one month of duration.

![]() Partial response is when there is at least a 30% reduction in the sum of the longest diameter of a target lesion when compared to the baseline study.

Partial response is when there is at least a 30% reduction in the sum of the longest diameter of a target lesion when compared to the baseline study.

![]() Progressive disease is when there is at least a 20% increase in the sum of the longest diameter of target lesions, appearance of new lesions, or the death of the patient as a result of the tumor. Chemotherapy is discontinued in the setting of progression, and the patient is reevaluated.

Progressive disease is when there is at least a 20% increase in the sum of the longest diameter of target lesions, appearance of new lesions, or the death of the patient as a result of the tumor. Chemotherapy is discontinued in the setting of progression, and the patient is reevaluated.

![]() The term stable disease is used when the measurable disease does not meet the criteria for complete response, partial response, or progression. Stable disease represents a difficult challenge to oncologists. If therapy is tolerated with no significant side effects, it is often continued, provided it is recognized that progressive disease will eventually occur.

The term stable disease is used when the measurable disease does not meet the criteria for complete response, partial response, or progression. Stable disease represents a difficult challenge to oncologists. If therapy is tolerated with no significant side effects, it is often continued, provided it is recognized that progressive disease will eventually occur.

OUTCOME/PROGNOSIS

Goals of Care

When a patient is diagnosed with cancer, one of the first questions an oncologist will be asked is: “How long do I have?” It is not the oncologist’s place to assign a life expectancy to any one patient. Each clinical scenario is different; to speculate on life expectancy can have serious emotional ramifications. An individual’s prognosis is based on staging, comorbidities, performance status, and response to treatment. Although it is possible to predict curability or median survival, long-term follow-up is essential to get a more accurate sense of prognosis for any given patient. Even when the overall prognosis is poor, an honest and compassionate discussion with the patient and family members is essential. The role of the medical oncologist is to provide upfront and honest answers to even the most difficult questions and to allow the patient and family to set realistic goals that will help guide future health care decisions.

Palliative Care

Palliative care of cancer patients entails the management of all of the symptoms related to the cancer itself and the toxicities of treatment. It also includes the multidisciplinary care of psychosocial issues, with the primary goal of optimizing the quality of life and minimizing the morbidity and symptoms related to cancer and its treatments. Prolongation of survival is a secondary goal, which may or may not be achieved, but cure is not the primary intent in palliative care. Chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, radiation, and surgery are still useful in palliation. Patient selection for interventions is crucial. For patients with advanced cancer and poor performance status, aggressive treatment may be detrimental rather than beneficial.

Hospice

Hospice is a philosophy of care based on a coordinated program of support services for terminally ill patients and their families. Palliative care is provided with the aim to improve quality of life and allow a comfortable death. Any patient with a limited life expectancy (≤6 months) may be eligible for hospice care. The interdisciplinary hospice team consists of nurses trained in pain and symptom management, physicians, home health aides, social workers, chaplains, and volunteers. Care is generally given in the home but may be imparted in nursing homes or hospitals if necessary. Medicare hospice benefits also include complete coverage for all medications pertaining to the hospice diagnosis, durable medical equipment, and oxygen. Most hospice agencies provide 24-hour on-call service, brief respite care, and bereavement counseling for up to one year after the patient dies.

REFERENCES

1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300.

2. Brown JR, Skarin AT. Clinical mimics of lymphoma. Oncologist. 2004;9:406–416.

3. Torigian DA, Huang SS, Houseni M, et al. Functional imaging of cancer with emphasis on molecular techniques. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:206–224.

4. Jaffe CC. Measures of response: recist, who, and new alternatives. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3245–3251.

5. http://imaging.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/imaging.