Kenneth J. Neuburger

Cutaneous lesions are often the first clinical sign of serious systemic disease. In this chapter, the focus is on the recognition and acute management of the common life-threatening dermatoses listed in Table 170.1. These disorders can be conveniently grouped into diffuse red rashes, vesiculobullous eruptions, localized or discrete lesions, and purpuric or hemorrhagic lesions (Table 170.2). The following dermatologic findings should alert clinicians to a potentially serious eruption (1):

• Confluent erythema

• Facial edema or central facial involvement

• Skin pain

• Palpable purpura

• Skin necrosis

• Blisters or epidermal detachment

• Positive Nikolsky sign

• Mucous membrane erosions

• Urticaria

• Swelling of tongue

Several entities are not discussed in detail here but deserve brief mention. Palpable purpura is a skin manifestation of vasculitis; it is not a manifestation of thrombocytopenia or clotting disorder. Involvement may be limited to the skin or may be systemic. Treatment is for the underlying vasculitic disorder.

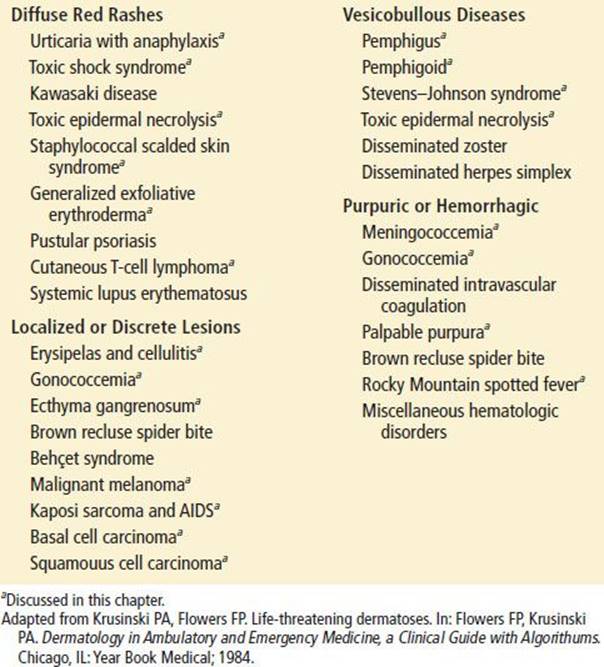

TABLE 170.1

Life-Threatening Dermatoses

TABLE 170.2

Identification of Life-Threatening Diseases Associated with Fever and Rash

Generalized exfoliative erythroderma (formerly called exfoliative dermatitis) is a diffuse, widespread dermatitis that covers most of the body surface. This condition not only causes pruritus and pain but may be complicated by hypothermia; fluid, electrolyte, and protein loss; invasion of bacteria and opportunistic organisms through the skin; and high-output congestive heart failure secondary to severe vasodilatation. The causes of exfoliative erythroderma include previously existing skin diseases (e.g., psoriasis, atopic eczema, contact dermatitis) (50%); drug eruptions (10%); lymphoproliferative disorders (e.g., Hodgkin disease, leukemia, Sézary syndrome) (15%); and idiopathic (25% to 40%). Mortality is <5%.

Other potentially life-threatening entities, such as angioedema (see Chapter 176) and disseminated herpetic infection, are discussed in other chapters.

Finally, a brief discussion at the end of the chapter focuses on the recognition of the various types of skin cancer.

DIFFUSE RED RASHES

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) (Fig. 170.1) occurs in children and, rarely, adults and is caused by an exotoxin from an infecting strain of coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus. The disease may present as a prodrome of fever, irritability, malaise, and exquisite skin tenderness; in other cases, the child presents with the sudden onset of generalized erythema. The skin is red, warm, and very tender. Ill-defined, flaccid bullae then desquamate in large sheets. Gentle lateral stroking of the skin causes the epidermis to separate (Nikolsky sign).

Therapy consists of systemic antibiotics effective against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus (due to its increased incidence). Children older than 1 year and with mild symptoms may be treated as outpatients. Children who appear toxic and infants should be admitted. Despite proper treatment, most of the superficial body surface will desquamate but, because the site of blister cleavage is in the superficial layer of the epidermis, healing occurs rapidly over 7 to 14 days.

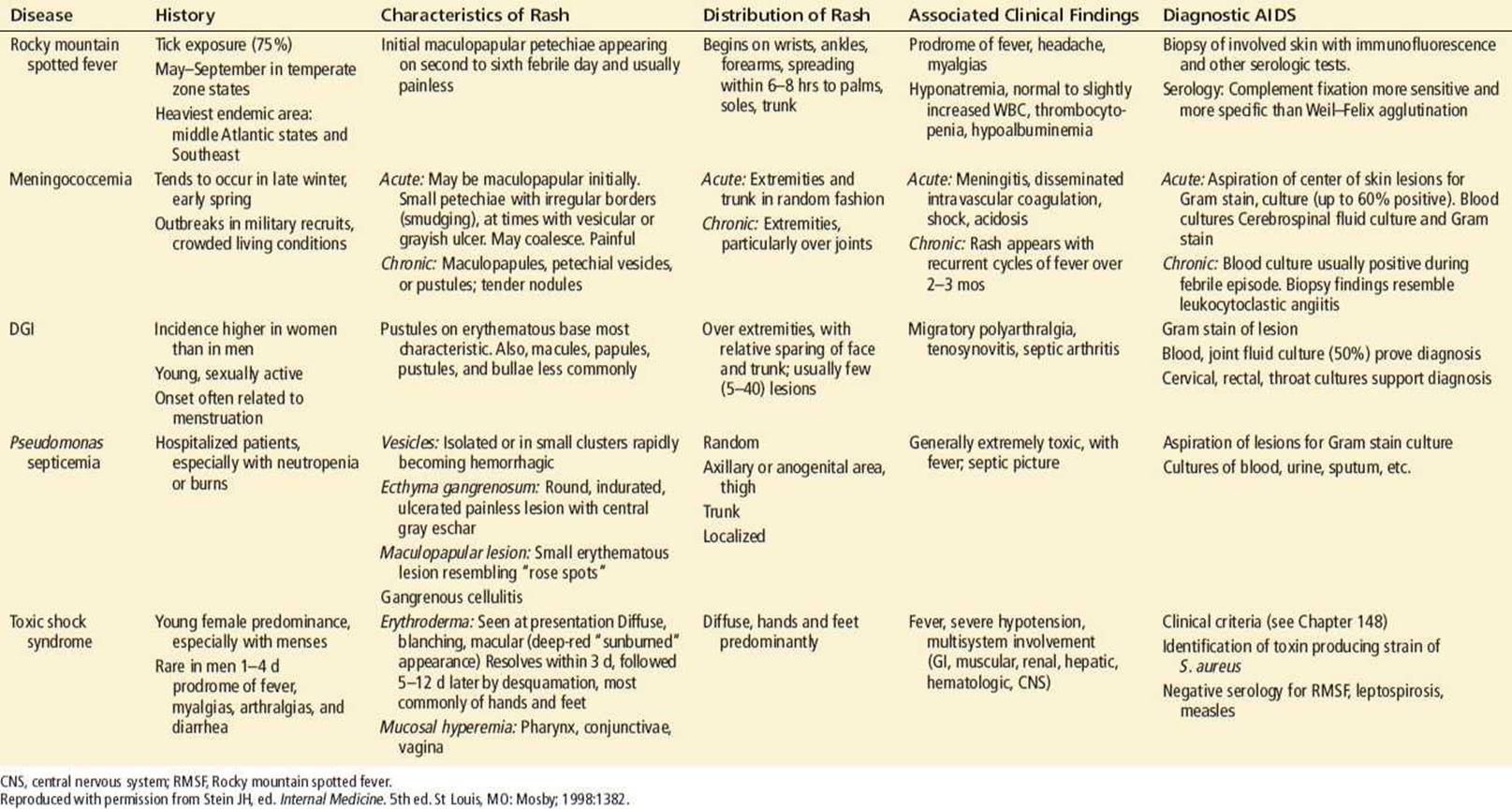

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (Fig. 170.2) is a disease of adults in which the skin also sloughs in large sheets. Although it is very similar in appearance to SSSS, it is quite different. It has been accepted that erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome (discussed later in the chapter), and TEN are a progression of severity of the same disorder (2). All usually start with a prodrome of fever, malaise, and myalgia. The skin is initially diffusely painful, hot, and red. Within days, blisters and large areas of denuded skin develop; erosive, sloughing lesions of the oral mucosa are common. The Nikolsky sign is positive.

The differences between TEN and SSSS are noteworthy. SSSS almost always occurs in children and is secondary to staphylococcal infection. TEN almost always occurs in adults and is most often precipitated by drugs such as phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, antibiotic sulfonamides, allopurinol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (3). About 62% are probably caused by medications, 23% possible, and the other 15% unlikely to be drug related (3). Mucous membrane involvement in SSSS is rare and limited to the lips but, in TEN, erosive oral lesions are common. Although SSSS sloughs only the superficial layers of epidermis, TEN desquamates the entire thickness of the epidermis, accounting for the high associated mortality rate. The mortality rate in SSSS is very low, whereas that of TEN can be >50%.

The diagnosis of TEN is made by clinical presentation and confirmed by biopsy. Treatment is removal of the precipitating agent, if possible, and consists of judicious fluid, electrolyte therapy, and prevention of infection (4). Early transfer to a burn center is standard of care (4). There are conflicting studies concerning use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in the therapy for TEN (4). IVIG, if used, should be started early in the course at doses of 1 g/kg daily (5) up to 2 to 3 g/kg daily for 4 to 5 days (4,5). Corticosteroid treatment is being reevaluated as it may or may not be useful depending on dosing, and time of use in the disease process. There are case reports of rapid improvement with cyclosporine, administered 3 to 10 mg/kg daily for 8 days to weeks (4,5). Plasmapheresis, antitumor necrosis factor therapy, and N-acetylcysteine treatments show some promise, but need further study (4,5).

FIGURE 170.1 Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. A 10-day-old Caucasian boy with staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. He was treated with fluids, oral dicloxacillin, and wound care. His skin healed completely and without scarring within 2 weeks of this photograph being taken. (From Avery GB, Fletcher MA, MacDonald MG. Neonatology: Pathophysiology and Management of the Newborn. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:1199, with permission.)

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS; see Chapter 192) is an acute, febrile illness originally associated with localized infection by strains of S. aureus that produce an exotoxin (TSST-1) (6) that results in the clinical signs and symptoms. Currently enterotoxins A, B, C, G, H, and I have also been implicated in causing TSS (6,7). Characteristic signs and symptoms include an early macular rash, hypotension, abnormalities in multiple organ systems, and acral desquamation occurring 1 to 2 weeks after the onset of the illness (Fig. 170.3). Originally about 90% of the S. aureus isolates from patients with TSS produce the exotoxin. Eighty-five percent to 90% of cases were reported in menstruating women (6,8). In fact, the disease was originally described in association with the use of highly absorbent vaginal tampons that could be kept in place for many hours before being discarded (6). Other cases are associated with localized infection in men, children, and nonmenstruating women (9). A new population assessment was done in 2000–2006 with 61 cases (33 menses related and 28 other sites). TSST-1 was found in 80% of isolates and more prevalent in menstruating than nonmenstruating situations (89% vs. 50%). Enterotoxins A, B, and C were found more often in nonmenstrual infections versus menstrual (100% vs. 25%). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) was found in four cases (8).

FIGURE 170.2 Toxic epidermal necrolysis that may extend into the reticular dermis (deep partial thickness) or the papillary dermis (superficial partial thickness). The peripheral zone of hyperemia correlates with a superficial or first-degree burn and might be similar to a sunburn. (From Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, et al. Greenfield’s Surgery Scientific Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.)

FIGURE 170.3 Toxic shock syndrome. Desquamation of the skin of the palm in a patient with staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome. (From Sweet RL, Gibbs RS. Atlas of Infectious Diseases of the Female Genital Tract. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005, figures 9–2.)

The early cutaneous rash is scarlatiniform and blanches with pressure; it can be difficult to appreciate because it is often quite pale. Coincident with the rash, there is often erythema of the mucous membranes of the oropharynx, conjunctivae, and vagina. Desquamation of the skin of the distal extremities occurs 1 to 2 weeks after the onset. Hair and nail loss follows 1 to 2 months later.

Strict criteria for the diagnosis of TSS are fever, hypotension or orthostasis, an erythematous macular rash, involvement of at least three organ systems, and the presence of an S. aureus infection. Most patients have facial and extremity edema. The illness can proceed rapidly. Hypotension may appear early; most patients present to the hospital with at least orthostasis.

The differential diagnosis of TSS includes Rocky mountain spotted fever (RMSF), scarlet fever, sepsis, Kawasaki disease (rare in those older than 8 years), leptospirosis, Colorado tick fever (in which photophobia is common), and other viral infections. Supportive treatment for dehydration and hypotension includes fluid replacement and the use of pressors, if necessary. The adult respiratory distress syndrome is common in serious cases.

Although it has not been proven that antibiotics are always necessary for recovery, provided the site of located staphylococcal infection is removed (e.g., removal of tampons or incision of abscesses). While awaiting culture results, treatment should cover MRSA. Vancomycin plus clindamycin, or linezolid alone are appropriate. Clindamycin and linezolid both decrease toxin production while vancomycin does not (9).

IVIG should be considered in those with a poor response to intensive therapy after several hours (less than 6 hours). The dosing is not well defined but should probably be greater than the original study dose of 1 g/kg the first day and 0.5 g/kg on days 2 and 3 (9). Because TSS recurs in a large percentage of women with tampon-associated TSS who continue to use tampons, women with a history of TSS should no longer use tampons. All symptomatic patients suspected of having TSS require admission for vigorous supportive treatment.

The hallmark of streptococcal TSS, first described in the mid-1980, is a relatively early onset of shock and multiorgan failure. The currently proposed criteria for streptococcal TSS are isolation of group A streptococci from a sterile or nonsterile site, hypotension, and at least two of the following: renal impairment, coagulopathy, liver function test abnormalities, adult respiratory distress syndrome, soft-tissue necrosis, and rash (which may be generalized macular or possibly scarlatiniform and may desquamate) (6,10). Treatment is with high-dose penicillin (20 to 24 million units/d); cephalosporins, clindamycin, erythromycin, vancomycin, and penicillinase-resistant penicillins are also effective. Cases with an indeterminate source should be treated as in staphylococcal toxic shock. Aggressive supportive care is mandatory, as is surgical drainage or debridement for abscess, pyonecrosis, or necrotizing fasciitis. Again, IVIG is recommended if an adequate response is not seen within 6 hours. The IVIG dose should be 1 g/kg on day 1 and 0.5 g/kg on days 2 and 3 (9). Even with prompt treatment, mortality ranges between 20% and 30%.

VESICOBULLOUS DISEASES

The spectrum of acute, self-limited immunologic reactions causing vesicles includes bullous erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and TEN. These are probably the same disease with increasing severity and more skin and mucous membrane involvement (11). The causes are the same as those listed in the previous discussion of TEN, although erythema multiforme can be related to herpes simplex and mycoplasma, and Stevens–Johnson syndrome is usually related to drugs. The classic lesion of erythema multiforme is the target lesion, a central gray wheal or bulla surrounded by concentric rings of erythema and normal skin. As the name implies, however, many types of lesions may be present simultaneously: macules, papules, urticaria (though non pruritic), and bullae. The extremities are involved more than the trunk; the palms and soles are often affected. The rash appears abruptly and may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and pruritus.

Farther along the spectrum is bullous erythema multiforme, with less than 10% skin involvement and target lesions, followed by Stevens–Johnson syndrome, with 10% to 30% skin involvement (11) accompanied by constitutional symptoms and affecting at least two mucous membranes. A prodrome of fever, malaise, and myalgia is followed by the explosive appearance of blisters on mucous membranes and skin. Symmetric blistering begins on the dorsa of the hands and feet and on extensor surfaces. Erosive lesions begin on oral mucosa, lips, and bulbar conjunctiva and can extend to the pharynx, larynx, esophagus, and genital mucosa (Fig. 170.4). Ocular lesions can result in corneal ulceration, panophthalmitis, and even blindness, requiring early recognition and treatment. The prognosis of Stevens–Johnson syndrome is usually good (7). However, the disorder may progress to an illness clinically indistinguishable from TEN, with large confluent bullae and sloughing of epidermis in sheets.

FIGURE 170.4 Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Erythema multiforme major (Stevens–Johnson Syndrome). Bullae and crusts are noted on the lips, and targetoid lesions are seen on the hand. (From Goodheart HP, MD. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

Milder cases of Stevens–Johnson syndrome can be treated with oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids; more severe cases require hospital admission. More severe cases can be treated as noted for TEN earlier in the chapter. Corticosteroids, antitumor necrosis factors and N-cetylcysteine need to be further evaluated before they can be recommended for treatment (4,7).

PEMPHIGUS VULGARIS

Pemphigus vulgaris, a rare disease, occurs mostly in adults 40 to 60 years old and is distinguished from other blistering diseases by its fulminant course. Early identification and aggressive treatment may avert a poor outcome. Initially, blisters may be localized to small areas of the mucous membranes or skin; lesions may be present for months before the blistering becomes generalized. The lesions are typically painful flaccid bullae that may rupture easily or painful erosions where bullae have ruptured (Fig. 170.5). They have a predilection for the scalp, face, chest, axillae, and groin. These painful erosions or collapsed bullae can persist despite successful treatment of skin lesions. The Nikolsky sign is positive. Half of patients present initially with oral lesions; 90% have oral lesions at some time during the course of the illness.

FIGURE 170.5 Pemphigus vulgaris. A: Bulla. B: Erosion. (From Berg D, Worzala K. Atlas of Adult Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

The diagnosis of pemphigus is made by biopsy of intact skin adjacent to a bulla. Direct immunofluorescent staining for antiepithelial antibodies localized to the epidermal cell membrane is confirmatory. Indirect immunofluorescence of the patient’s serum or blister fluid detects a pemphigus antibody that reacts with epithelial cell membranes of most species. Therapy is with corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disease occurring mostly in the elderly. The bullae of bullous pemphigoid, unlike those of pemphigus vulgaris, are tense rather than flaccid, and oral lesions are less common The Nikolsky sign is negative. Bullous pemphigoid is characterized by spontaneous remissions and exacerbations and a low mortality rate; most patients experience complete remission. As with pemphigus vulgaris, the diagnosis is made by biopsy of the skin adjacent to a blister. Direct immunofluorescence studies reveal antibodies bound to the basement membrane; these antibodies can often be found in the serum as well. Mild cases are treated with topical corticosteroids or intralesional injections; severe cases require systemic corticosteroids with or without immunosuppressive agents.

LOCALIZED OR DISCRETE LESIONS

Patients with gram-negative sepsis may manifest the skin lesions known as ecthyma gangrenosum (Fig. 170.6). Originally described in Pseudomonas septicemia, they may also occur with bacteremia due to Escherichia coli or Klebsiella and have been reported in the absence of disseminated infection (12). Because the lesions of ecthyma gangrenosum are manifestations of life-threatening illness, the diagnosis must be made early. Ecthyma gangrenosum is a true dermatologic emergency; patients with it are critically ill and usually immunocompromised (e.g., with leukemia or lymphoma). Treatment with newer antimicrobial regimens for carbapenemase-producing organisms may be needed in select cases (13).

FIGURE 170.6 Ecthyma gangrenosum. (From Berg D, Worzala K. Atlas of Adult Physical Diagnosis. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.)

The appearance of the lesion can vary, depending on the stage of the illness at presentation. Beginning as a painless macule or vesicle, it indurates and assumes the appearance of a pustule or bulla on a blue or red base. The lesion then sloughs, leaving a gangrenous ulcer, usually several centimeters in size. These solitary or multiple lesions usually occur mainly in the perineal region or on the extremities.

Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) usually occurs in individuals with asymptomatic infection of the pharynx, rectum, or genitalia. The patient commonly presents with fever, skin lesions, arthritis, periarthritis, tenosynovitis, or any combination of these signs. DGI occurs most commonly in women during menstruation or pregnancy, but it can occur in any patient with gonococcal infection.

The skin lesions are pustules or vesicles on an erythematous base about 5 mm in diameter, but they may also be petechial, bullous, papular, or hemorrhagic. These are usually relatively few (fewer than 10 to as many as 30), and they typically appear on the extremities and resolve rapidly (usually in <1 week). The periarthritis of DGI presents with joint swelling and tenderness, which are often transient and migratory. Septic arthritis occurs most commonly in the larger joints (knees, hands, ankles, and elbows, in descending order of occurrence). Complications such as endocarditis, meningitis, and sepsis are rare.

The diagnosis of gonococcemia (Fig. 170.7) is a clinical one. Any sexually active person with polyarthritis, tenosynovitis, and typical skin lesions can be given a presumptive diagnosis of gonococcemia with little doubt as to its accuracy. Gonococcal cultures or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing should be performed on specimens obtained from all mucous membrane surfaces and blood and (when appropriate) joint fluid. The diagnosis can also be made on the basis of a prompt response to empiric antibiotic treatment (see Chapter 184). Antibiotic treatment regimes include ceftriaxone 1 g IV or IM daily plus azithromycin 1 g orally or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days. It is important to follow the most current CDC recommendations closely, as resistance patterns change (14).

FIGURE 170.7 Disseminated gonococcemia. Neisseria gonorrhoeae may disseminate from mucosal surfaces via the bloodstream and produce arthritis/arthralgia and a rash. The most characteristic lesion is the hemorrhagic vesicopustule seen in the web space of the teenage girl’s hand. There is a pustule on the sole of her foot. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig W, Baskin MN. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.)

The differential diagnosis should include Reiter syndrome (a syndrome of urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis that usually occurs after a diarrheal illness, has dissimilar skin lesions, and does not respond to antibiotics); meningococcemia (which has more numerous petechial lesions); immune complex diseases (which may have joint manifestations but a different type of skin lesion); and rheumatic fever.

Admission is indicated only for patients with severe systemic signs and symptoms or severe joint involvement (especially of weight-bearing joints) and those who cannot be followed closely as outpatients.

Erysipelas is a superficial cellulitis that progresses rapidly in extent and involves the associated lymphatic channels. The classically described offending organism is the group A streptococcus, but groups B, C, and G streptococci and S. aureus have also been isolated (15). The infection is most common in infants and children and in the elderly. The source in most cases is probably an inapparent wound. Erysipelas may range from a self-limited process that resolves spontaneously, even without antibiotics, to a rapidly progressive and severe infection leading to bacteremia. Admission is indicated for patients with extensive facial or neck involvement or for patients with fever and a toxic appearance.

The involved skin is erythematous, warm, and tender to palpation and has an advancing margin that is slightly elevated. Fever is common. The diagnosis is usually clinical, because local aspiration is rarely positive. Punch biopsy may be useful, but it is usually not readily available. The differential diagnosis includes cellulitis, maxillary or frontal sinus infections (if localized to the face), and erysipeloid (if localized to the hands).

Treatment with penicillin is rapidly effective if erysipelas is due to streptococci, but, because it is rarely easy to identify the causative organism, either a first-generation cephalosporin or a penicillinase-resistant penicillin should be used to cover methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus. Clindamycin, vancomycin, or linezolid should be used if MRSA is possible, and may be used in the penicillin-allergic patient. Hospital admission is based on the patient’s clinical status. Some affected individuals may be treated as outpatients with close follow-up and admitted if there is no response or any worsening after 1 to 2 days of oral antibiotic therapy.

Cellulitis, an acute, spreading inflammation of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, appears as a warm, tender, erythematous area with indistinct margins. Its differentiation from erysipelas is based on the appearance of the advancing edge of the infection. In cellulitis, the edge is not raised. In practice, the clinical management of patients with erysipelas and with cellulitis is similar. Erysipelas is more likely, however, to require prompt initiation of antibiotic therapy because it can progress so rapidly.

PURPURIC OR HEMORRHAGIC LESIONS

Neisseria meningitidis colonizes the nasal mucosa in humans (5% to 15%) but may invade the bloodstream and cause disease. Most cases occur in children and adolescents, although any age group may be affected. The mortality of meningococcemia is higher than that of meningococcal meningitis.

Meningococcemia (Fig. 170.8) usually follows an upper respiratory tract infection with flu-like symptoms of headache, myalgias, nausea, and vomiting. The severity of the disease can range from an indolent, slowly evolving infection to a fulminating illness causing prostration within a few hours after the onset of symptoms. The classic skin lesions can be petechial, macular, or maculopapular with pale gray vesicular centers. All are a few millimeters in size but may progress to a confluent hemorrhagic rash. They are most commonly localized to the extremities and trunk but may appear on any part of the body. Meningitis presents with the usual symptoms of meningeal irritation—neck soreness, photophobia, headache—whereas, in meningococcemia, meningeal signs are typically absent (16).

FIGURE 170.8 Meningococcemia. Infection with Neisseria meningitidis. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig W, Baskin MN. Atlas of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.)

Gram stain and culture of scrapings of the skin lesions are positive in only about half of cases. The diagnosis must often rest on clinical findings and is confirmed by positive cultures of blood or cerebrospinal fluid.

One should entertain the diagnosis of meningococcemia in any patient who presents with fever, malaise, and a petechial or maculopapular rash and include it in the differential diagnosis of other bacteremias (e.g., Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. aureus), subacute bacterial endocarditis, gonococcemia (few distal papular, hemorrhagic lesions), vasculitis (usually distal purpuric lesions), enteroviral exanthems, and RMSF.

The treatment of choice for meningococcemia is high-dose IV antibiotics. Penicillin G (2 million units every 2 hours), ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours), chloramphenicol (4 g/d), and ceftriaxone (up to 4 g/d [100 mg/kg] in children) have all been shown to be effective. Complications such as shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, adult respiratory distress syndrome, or metabolic acidosis require aggressive supportive care. Prophylaxis is recommended for close school and household contacts. Rifampin, 600 mg (10 mg/kg for children, 5 mg/kg for infants younger than 1 month), is given orally twice daily for 2 days. Single-dose therapy of ciprofloxacin, 500 mg orally, or ceftriaxone, 250 mg IM, are also alternatives for adults.

A related syndrome, chronic meningococcemia, presents as periodic fever, localized rash, myalgia, and arthralgias lasting for several days. The number of skin lesions is small. Episodes may recur over a period of weeks to months. The diagnosis is established by positive cultures (especially of blood) during the febrile episodes. A fair percentage of patients proceed, if untreated, to an acute phase of disease. The differential diagnosis includes subacute bacterial endocarditis, rheumatic fever, gonococcemia, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura.

Treatment is the same as for acute meningococcal disease, except that lower doses of IV antibiotics are generally considered sufficient to eradicate the infection. All patients suspected of having meningococcal disease should be admitted to the hospital for evaluation and treatment, regardless of clinical appearance.

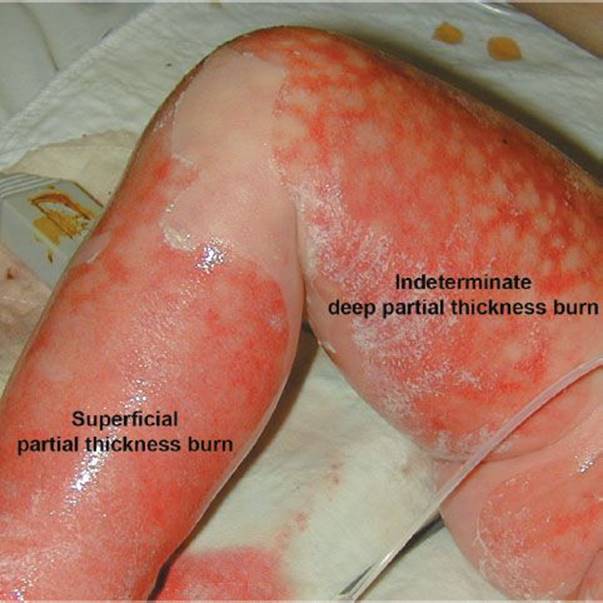

RMSF (see Chapter 186) is an acute infectious disease caused by Rickettsia rickettsii and transmitted by the bites of several species of ticks (Dermacentor andersoni in the western US, Dermacentor variabilisin the eastern US, and Amblyomma americanum in some southwestern areas) (Fig. 170.9). RMSF is not limited to the Rocky mountain area; in fact, the areas of highest incidence are in the South Atlantic region and western south-central states. The organisms can be introduced directly into the skin by a tick bite or may enter broken skin with the tick’s feces. Once the infection is established, the organisms invade vascular endothelial cells, causing localized thrombosis and necrosis. The disease is manifested clinically by fever, rash, myalgia, and headache. It ranges in severity from a mild, self-limited illness to severe, life-threatening disease (17).

FIGURE 170.9 Rocky mountain spotted fever. (Courtesy of Sidney Sussman, MD.)

RMSF is seen most commonly in the late spring and early summer. The incubation period ranges from 3 to 12 days. There is an abrupt onset of fever, chills, arthralgia, and headache, which is usually severe, with or without nausea, vomiting, and photophobia. The rash appears between the second and sixth days of the illness, beginning peripherally on the wrists, ankles, and forearms as a macular erythematous rash and extending to the palms, soles, and torso. The lesions become maculopapular in a few days in most cases and become petechial shortly thereafter (2 to 4 days after the start of the rash). The rash may be absent in 12% to 17% of cases and may be difficult to appreciate in dark-skinned individuals (1). Areas of decreased circulation, such as the distal extremities, nose, and ear lobes, may develop areas of infarction; finding such lesions on the scrotum or vaginal area can be an additional clue to the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis of RMSF includes TSS, meningococcal meningitis, Kawasaki disease, measles, leptospirosis, Colorado tick fever, enteroviral infections, any cause of disseminated intravascular coagulation and vasculitis, mononucleosis, rat-bite fever, atypical measles, and other rickettsial diseases. Among the latter are murine typhus and epidemic typhus, which both have rashes that usually begin on the trunk rather than on the distal extremities.

The treatment of choice for RMSF is doxycycline (100 mg every 12 hours) for 7 to 10 days or tetracycline (25 to 50 mg/kg in divided doses four times daily, not to exceed 2 g/d). Years ago because of concern over dental effects of tetracycline, chloramphenicol (50 to 100 mg/kg/d in four divided doses) was used to treat children, and is currently recommended in pregnancy. Tetracycline usually does not affect enamel formation in the incisors, canines, and bicuspids after age 7 (18,19). Moreover, in children younger than 5 years, it is unlikely to result in any apparent change in tooth color when fewer than five courses of therapy are given in the usual oral dosage (18,19). More recent studies on tooth enamel staining have not shown staining in teeth owing to short courses of doxycycline in children ages 2 to 8 years (18,20) and with an average age of 5 years (18,20). The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Disease revised their recommendations in 1997 and named doxycycline as the antibiotic of choice for treating possible or confirmed RMSF and ehrlichial infections in children, regardless of age. The dose of doxycycline in children weighing <100 lb is 2.2 mg/kg body weight in divided doses twice daily. The adult dose is 100 mg twice daily.

SKIN CANCER

Skin cancers are life-threatening if not diagnosed early. Yet early diagnosis can lead to cure rates in more than 90% of patients in the most common types of skin cancer. Discussion in this chapter focuses on clinical recognition as described further, illustrated with supplementary photographs. As management is primarily by the dermatologist, definitive diagnostic points and treatment are discussed only briefly.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) (Fig. 170.10) is the most common skin cancer. It is usually found in men older than 50 years. Ninety percent are on the sun-exposed head and neck, with the trunk being the next most common site. There are four types. The noduloulcerative BCC begins as a small pearly papule that enlarges over the years into a nodule with a waxy edge, a few telangiectatic vessels, and an ulcer on the surface. The pigmented type looks the same with the addition of some black or brown pigment. Sclerosing basal cell cancer, usually on the face, looks like a whitish scarred patch without any ulceration or telangiectases. Superficial basal cell cancer is the most innocuous-looking, resembling a dermatitis. It usually appears on the back and the chest and it looks like a reddish patch with slight scale. The border may have telangiectatic vessels and be slightly raised. The center may be atrophic with superficial ulceration.

FIGURE 170.10 Basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Pearly papule: The tumor exhibits typical rolled pearly borders with telangiectases and central ulceration. (From Elder AD, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, et al. Synopsis and Atlas of Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999, p 2, clin. fig. IA1; p 163, clin. fig. IVE3; p 167,.)

Squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 170.11) accounts for 20% of all skin cancer other than melanoma. It occurs most commonly on sun-exposed areas of the face, scalp, lip, ear, and neck and the dorsal hand. Scars from radiation or burns may develop squamous cell carcinoma and are more likely to metastasize. The most common lesion is a quickly growing nodule with an ulcerated center and a firm raised border surrounded by redness. Cure rates are 90%, and metastasis (4% overall) manifests as regional lymphadenopathy.

FIGURE 170.11 Squamous cell carcinoma. A: This neglected tumor has ulcerated. B: This reddish nodule is indistinguishable from BCC. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

Malignant melanoma (Fig. 170.12) is a pigmented skin cancer developing on previous nevi or de novo on sun-exposed areas, such as the face and forearms, or on the back of men and the lower legs of women. Amelanotic melanomas are rare and challenging to diagnose. Although melanomas make up only 1% of the skin cancers in the US, they account for >60% of the deaths. Yet, the most common type, the superficial spreading melanoma, has 5-year survival rates of almost 98% when thin and removed early. It has five cardinal features (5):

FIGURE 170.12 Malignant melanoma. Note the variegation in color and the irregular, notched border. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

1. Asymmetry

2. Border is irregular

3. Color is mottled, haphazard display of brown, black, gray, and pink (beware of no color in amelanotic melanoma)

4. Diameter >6 mm (the size of a pencil eraser)

5. Enlargement growth in size; elevation, usually with surface distortion (2)

Changes in a recent or longstanding skin lesion that are suspicious include changes in size, shape, pigmentation, surrounding erythema, induration, friability, and ulceration (9).

Diagnosis of all the skin cancers relies on early clinical suspicion and referral to a dermatologist for diagnosis by removing the lesion for pathologic diagnosis and staging. Additional chemotherapy or radiotherapy may be indicated for metastasis squamous cell carcinoma or advanced melanoma.

Kaposi sarcoma (Fig. 170.13) is a vascular neoplasm seen in the United States, mostly in patients with AIDS and low CD4 cell counts. With the advent of effective therapy to manage HIV, Kaposi is uncommonly seen now. It can also occur sporadically in elderly men and in Europeans and Africans unrelated to their HIV status.

FIGURE 170.13 Kaposi’s sarcoma. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

It appears as red, purple, or brown papules or plaques, solitary or multiple, on skin or mucous membrane. Internal organs may be involved as well, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and lungs. Diagnosis is made by clinical appearance in the appropriate individual. Management focuses on controlling the underlying disease.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides; Fig. 170.14) is a cancer of CD4 cells. It usually affects people in their forties and fifties, twice as many men as women, twice as many blacks as whites. They report asymptomatic or pruritic patches of abnormal-appearing skin unresponsive to treatment. Occasionally, they may have fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Sezary syndrome is considered to be an erythrodermic, leukemic variant of mycosis fungoides with generalized erythroderma, lymphadenopathy, and atypical T-cells (Sezary cells) in the peripheral blood. Patients with Sézary syndrome have a worse prognosis than those with mycosis fungoides and erythroderma but without lymphadenopathy and atypical T-cells in the blood (6). The diagnosis is made by multiple lesional biopsies over time. Treatment can either be systemic for more advanced disease or related to the skin disease.

FIGURE 170.14 Mycosis fungoides. A: A 66-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of erythematous scaly patches and plaques with telangiectases, atrophy, and pigmentation. (From Elder AD, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL, et al. Synopsis and Atlas of Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999, p 2, clin. fig. IA1; p 163, clin. fig. IVE3; p 167,.) B: Lesions have characteristic “smudgy,” poorly defined patches and plaques in a typical location. (From Goodheart HP. Goodheart’s Photoguide of Common Skin Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS

• Search for Nikolsky sign in diffuse red skin rashes.

• Initiate antibiotics for patients with suspected meningococcemia.

• Recognize that most melanomas are pigmented and develop changes in size, shape, and pigmentation.

Common Pitfalls

• TEN can easily be confused with SSSS. TEN requires the removal of any possible precipitating agent, most commonly a drug; SSSS must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. The prognosis of the two diseases is markedly different.

• The rash of TSS may be indistinct. The diagnosis should be considered in any patient with fever and signs of volume depletion, even in the absence of a history of tampon use. The disease can occur in men and children.

• Bullous pemphigoid can easily be confused with pemphigus vulgaris. Early consultation with a dermatologist may be necessary to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

• In a febrile, seriously ill patient, skin lesions may be a manifestation of sepsis. The lesions should be opened and their contents Gram-stained and cultured.

• Rapid identification and treatment are crucial in ecthyma gangrenosum. The underlying septic process can be fatal if not treated promptly.

• The diagnosis of gonococcemia is often overlooked in persons presenting with tendinitis without any history of injury.

• The early rash of meningococcemia may be macular, maculopapular, or petechial.

• In RMSF, the rash is absent in a significant proportion of cases. An increased index of suspicion is necessary for any patient presenting with a viral-like illness in the late spring or early summer.

• Although BCC is usually waxy and ulcerative, it may also appear to be an innocuous dermatitis.

• Asymptomatic or pruritic patches of abnormal skin which are unresponsive to treatment may represent cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

REFERENCES

1. Wright S. North American tick-borne diseases. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:964–972.

2. Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1272–1285.

3. Sassolas B, Haddad C, Mockenhaupt M, et al. ALDEN, an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Comparison with case-control analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther.2010;88(1):60–68.

4. Endorf FW, Cancio CC, Gibran NS. Toxic epidermal necrolysis clinical guidelines. J Burn Care Res. 29(5):706–712.

5. Valeyrie L, Allanore RJ, Epidermal Necrolysis. In: Goldsmith LA, ed. Fitzpatricks Dermatology in General Medicine. McGraw Hill; 2012.

6. Davis JP, Chesury PJ, Ward PJ, et al. Toxic shock syndrome: epidemiologic features, recurrence, risk factors and prevention. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1429–1435.

7. Fernando SL. The management of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:165–171.

8. DeVries AS, Lesher L, Schlievert PM, et al. Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome 2000–2006: Epidemiology, clinical features and molecular characteristics. Plos One. 2011;6(8):e22997.

9. Lappin E, Ferguson AJ. Gram positive toxic shock syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:281–290.

10. The Working Group on Severe Streptococcal Infections. Defining the group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: Rationale and consensus definition. JAMA. 1993;269:390–391.

11. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens – Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch. Dermatology. 1993;129(1):92–96.

12. Fergie J, Patrick C, Lott L. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cellulitis and ecthyma gangrenosum in immunocompromised children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:496–500.

13. Tumbarello M Viale P, Viscoli C, et al. Predictors of mortality in bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella pneumonia carbapenemase – producing k. pneumonia: Importance of combination therapy clinical infectious diseases. 2012;55(7):943–950.

14. Update to CDC’s Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: Oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2012;61(31):590–594.

15. Gilbert DN, Moellering Jr RC, Eliopoulos GM, et al The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy. 2012.

16. Raman G. Meningococcal septicaemia and meningitis: A rising tide. BMJ. 1988;296:1141–1142.

17. Sexton D, Kaye K. Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86(2):351–360.

18. Lochary ME, Lockhart PB, Williams WT. Doxycycline and staining of permanent teeth. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17(5):429–431.

19. Grossman ER, Walchek A, Freedman H. Tetracyclines and permanent teeth. Pediatrics. 1971;47:567–570.

20. Volovitz B, Shkap R, Amir J, et al. Absence of tooth staining with doxycycline treatment in young children. Clin Pediatr. 2007;46(2):121–126.