Diane M. Birnbaumer and Daniel P. Runde

Abdominal pain is simultaneously one of the most common and challenging chief complaints in emergency medicine. Abdominal pain accounts for 8% of the >120 million annual emergency department (ED) visits and is among the top 10 most common reasons people come to the ED (1). Its causes range from benign processes that present with severe pain to fatal processes that present with subtle findings. Despite improving imaging modalities, patients with abdominal pain continue to be diagnostically challenging. Even in patients who have undergone an appropriate workup, approximately 30% of patients will be discharged with the diagnosis of undifferentiated abdominal pain.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The importance of a thorough history and physical examination is absolutely paramount, as it helps narrow the vast differential diagnosis and focuses diagnostic testing. Failure to actually gather the relevant information (history and physical examination) is a more frequent cause of misdiagnosis than is misinterpretation of the data gathered.

When obtaining the history and performing a physical examination, it is important to understand that there are three major types of abdominal pain: visceral, somatic, and referred pain. They differ based on the anatomic pathway relaying the pain signal.

Visceral pain is relayed by afferent visceral fibers that are located in the walls of hollow organs and capsules of solid organs. These fibers are stimulated by stretching, distension, and excessive contraction. The visceral pain fibers originate from both sides of the spinal column, and enter the spinal column at multiple levels. This results in the perception of a poorly localized, midline pain that is described as dull or aching.

Somatic pain results from irritation of the parietal peritoneum. Pain is relayed by myelinated, unilateral afferent fibers that travel to a specific level in the spinal cord, making this pain more localized. It is usually described as sharp, intense, and well localized. Somatic pain is responsible for the physical findings of tenderness to palpation, guarding, and rebound.

Abdominal pain often begins as visceral pain and then progresses to somatic pain as the inflammation spreads to involve the parietal peritoneum. As an example, the early epigastric pain of gallbladder distension is characteristic of visceral pain whereas the right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain caused by local peritoneal inflammation with cholecystitis is deep somatic pain.

Referred pain is discomfort perceived at a site distant from the diseased organ. The diseased organ and the body area to which the pain is referred have overlapping transmission pathways at the level of the spinal cord. A common example of referred pain is shoulder pain caused by irritation of the diaphragm from free air or blood. In the same manner, extra-abdominal organs may cause referred pain to the abdomen, such as myocardial ischemia or pneumonia causing epigastric pain.

History

When evaluating the patient with abdominal pain, a thorough history of the abdominal pain is crucial. Specifically, the physician should determine the onset, time course, character, location, aggravating and alleviating factors, associated symptoms, and whether there are previous episodes of abdominal pain. The general medical and social history should also be obtained, including past medical and surgical history, medications, allergies, tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug exposure, recent travel, and toxic exposures.

Onset

Sudden onset of severe pain is very concerning and is assumed to be due to a surgical condition, until proven otherwise. Vascular emergencies such as mesenteric ischemia or a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection and intestinal perforation, or torsion of a viscus may all present this way. Sudden onset of severe pain with an unimpressive physical examination is typical for a vascular catastrophe or torsed organ. Nonsurgical causes of abrupt onset of abdominal pain include renal colic and myocardial infarction. The physician should determine what the patient was doing when the pain began. Pain related to eating may be secondary to peptic ulcer disease, gallbladder disease, or mesenteric ischemia (intestinal angina). Pain that began during physical activity may be caused by a rectus abdominal muscle tear and hematoma, or myocardial ischemia.

Progression of Pain

The physician should question the patient about whether the pain is constant or intermittent and, if constant, whether it has been increasing or decreasing in severity. Pain that begins slowly and gradually progresses is typical of an inflammatory or infectious process such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, or salpingitis. Pain that is improving over time is less likely to be surgical in nature.

Location

In addition to onset, location may be one of the most useful pieces of information in determining the etiology of pain. Visceral pain is perceived either as epigastric, periumbilical, or infraumbilical, depending on the embryologic origin of the involved organ. Visceral pain tends to be poorly localized and midline whereas parietal (somatic) pain tends to be well localized and unilateral. It is important to determine whether the location has changed over time or radiates to a distant site.

Character

The severity and character of the pain are important historical factors. Dull aching pain is more likely to be visceral, and sharp pain is more likely to be somatic. Crampy intermittent pain is often because of bowel obstruction. Colicky pain often indicates nephrolithiasis or gallstone disease. Severe tearing back pain is classic for aortic dissection.

Aggravating and Alleviating Factors

The patient should be asked about how the pain changes with food, movement, position, or medications. Pain that is intensified by the car ride to the hospital or other movement is indicative of peritoneal irritation. The pain of pancreatitis is often exacerbated by lying in the supine position. The pain of myocardial ischemia may be relieved with rest.

Associated Symptoms

The physician should determine the presence or absence of fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, hematemesis, hematochezia, melena, dysuria, or hematuria. It is important to ask women about abnormal or increased vaginal discharge or vaginal bleeding and to ask men about testicular or penile complaints (swelling or pain). When patients complain of vomiting and abdominal pain, it is useful to determine which came first. Typically, in surgical diseases, the abdominal pain almost always precedes the vomiting, whereas the converse is true in most cases of gastroenteritis and nonspecific causes. As both cardiac and pulmonary processes can present with abdominal pain, an appropriate history should include questions about the presence of chest pain, shortness of breath, or cough. Also, the patient should be asked about the presence of flank or back pain. Patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, or renal colic may have pain that radiates to these areas.

Previous Episodes

Previous episodes of the pain should be investigated. Chronic recurrent abdominal pain involves a wide differential diagnosis; when obtaining the history, it is important to try to identify triggers of the abdominal pain. If the patient has undergone diagnostic studies in the past, there may be no point in repeating the workup unless there is a significant change in symptomatology or an emergent concern. If pain is recurrent, it may be related to the menstrual cycle. Pain that begins 2 weeks after the start of the menstrual cycle is suggestive of mittelschmerz, but this remains more or less a diagnosis of exclusion.

Past Medical History

Cardiovascular diseases including hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and valvular disease place patients at higher risk for vascular diseases such as mesenteric ischemia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and myocardial infarction. A gynecologic history should be obtained, including menstrual history, history of sexually transmitted diseases, and previous ectopic pregnancy.

Past Surgical History

Previous abdominal surgeries place patients at greater risk for conditions such as bowel obstruction resulting from adhesions (2).

Medications

A medication history should be obtained, including prescription medications, over-the-counter preparations, herbal supplements, and steroid use. It is essential to investigate any recent use of antibiotics which increases the risk of developing a Clostridium difficile infection. Certain drugs place patients at higher risk for hepatitis and pancreatitis.

Social History

Alcohol abuse increases the risk of gastroinestinal (GI) bleeds, pancreatitis, hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Heroin withdrawal may present with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Cocaine and amphetamine use may increase the risk of mesenteric ischemia.

Other

Recent traumatic events such as motor vehicle collisions or blows to the abdominal wall or back can result in rectus sheath hematoma, intraperitoneal bleeding, duodenal hematoma, or traumatic pancreatitis. A history of recent food intake, sick contacts, and travel is important for patients with suspected gastroenteritis. Finally, a history of any toxic exposures (e.g., lead) may also reveal the cause of the abdominal pain.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should always begin with an evaluation of the vital signs. When interpreting the vital signs, the emergency physician should take into account any medications that may affect heart rate or blood pressure (i.e., β-blockers). Tachycardia and hypotension should alert the physician to possible sepsis, dehydration from volume loss or third spacing, or hemorrhage from gastrointestinal bleeding, abdominal aortic aneurysm, or ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Fever makes an infectious etiology more likely, although absence of a fever should not be used to rule out an infectious cause of the pain. This is especially true in the elderly or immunocompromised patient who may present with infectious etiologies, but no fever. Because an oral temperature may be falsely low owing to factors such as mouth breathing or consumption of cold liquids, the more reliable rectal temperature should be obtained if infection is suspected. Tachypnea may be secondary to pain, hypoxia, sepsis, anemia, or metabolic acidosis. Pulse oximetry should be obtained to assess for hypoxia.

The general appearance of the patient may reveal clues to the diagnosis. A patient with peritonitis will lie still whereas a patient with renal colic may present writhing in the bed. The patient’s level of alertness, mental status, and orientation are also important. Lethargy and confusion are concerning for toxic ingestions, sepsis, or other causes of hypoperfusion.

The patient’s skin should be carefully examined. Pale, cool, diaphoretic skin suggests shock or a low-volume state (dehydration or bleeding). Jaundice may be present in patients with biliary or hepatic disease. The skin should be examined for rashes. Skin findings such as petechiae and spider hemangiomas are suggestive of liver disease. Whether the mucous membranes are moist or dry should be noted; dry membranes suggest dehydration. Oral thrush or hairy leukoplakia may indicate undiagnosed immunocompromise.

When examining the heart and lungs, the physician should listen for rales, rhonchi, wheezing, or other abnormal breath sounds that indicate a pulmonary etiology of abdominal pain. The patient’s rhythm and the presence of murmurs should be noted, as atrial fibrillation and valvular disease put patients at risk for mesenteric ischemia caused by emboli.

The abdominal examination should start with inspection. The physician should look for distention, hernias, and the presence of surgical scars and auscultate for bowel sounds noting their frequency, quality, and pitch. Obstruction and processes that cause inflammation within the GI tract result in increased bowel sounds whereas processes that cause inflammation outside of the GI tract such as peritonitis result in diminished bowel sounds. With obstruction, high-pitched tinkling bowel sounds may be present; in patients with an ileus, bowel sounds may be absent. Percussion may aid in the diagnosis of ascites, obstruction, organomegaly, or perforation, and tenderness to percussion may indicate peritonitis.

When palpating the abdomen, the physician should assess for location of tenderness, the presence of voluntary and involuntary guarding, and peritoneal signs. It is recommended to begin with gentle palpation, starting farthest away from the suspected location of tenderness. If the patient is able to tolerate gentle palpation, then deeper palpation should be used to localize the area of tenderness. Palpation at one location may cause pain at a different location. An example of this is seen in patients with appendicitis and is referred to as Rovsing sign (pain experienced at McBurney point during deep palpation of the left lower quadrant). The physician should examine for masses or organomegaly. In assessing for RUQ pathology, the physician should note the presence of a Murphy sign. During deep palpation of the RUQ, the patient is asked to take a deep breath. If inspiration is arrested in midcycle, this is suggestive of cholecystitis (positive Murphy sign). In elderly patients, the physician should assess for an abdominal aortic aneurysm by listening for bruits and assessing for the presence of an infraepigastric pulsating mass.

Voluntary guarding may be due to anxiety, fear, or discomfort. Maneuvers that aid in relieving voluntary guarding include warming of the hands, examination with the patient’s thighs flexed, deep inspiration by the patient, and reassurance from the physician. Involuntary guarding or rigidity will not resolve with these maneuvers and is more indicative of surgical disease. Peritoneal signs are markers of surgical disease. Classically, peritonitis was assessed by examining for the presence of rebound tenderness, increased tenderness when the examiner let go after deep palpation of the abdomen. Rebound tenderness may be present even in the absence of peritonitis, and some advocate using other methods to look for peritonitis. These include the cough test (the abdominal pain will worsen abruptly when the patient coughs), jostling the gurney, or striking the patient’s heels to precipitate the pain. Rigidity and peritoneal signs may be absent in the elderly even in the presence of peritoneal irritation and surgical disease. This may be attributed to the relatively thin musculature of the abdominal wall in older patients.

Carnett’s test can be used to help determine whether abdominal pain arises from the abdominal wall. While in the supine position, the patient is asked to lift the head off the stretcher, and the abdomen is palpated. If the source of the pain is intra-abdominal, the contracted musculature of the abdominal wall will provide shielding and diminish tenderness. If the source of pain is the abdominal wall, the tenderness will be the same or even increased.

It is important to examine for umbilical, inguinal, femoral, and surgical incision hernias, especially in the elderly. In this age group, approximately 10% of cases of obstruction are due to hernias, and they are often undiagnosed.

Examination of the back is necessary to check for costovertebral angle tenderness that may indicate either pyelonephritis or ureteral obstruction.

Women of childbearing age with lower quadrant or suprapubic pain should undergo a pelvic examination to aid in differentiating salpingitis or ovarian pathology from appendicitis or diverticulitis. The results of the pelvic examination should be interpreted carefully, as women with appendicitis may also have cervical motion tenderness and adnexal tenderness. Adnexal or cervical motion tenderness suggests pelvic inflammatory disease; if present, mucopurulent discharge from the cervical os increases the likelihood. In women with RUQ pain, particularly if evaluation for gallbladder disease is negative, the pelvic examination may also be helpful. Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, a perihepatitis caused by pelvic inflammatory disease, may present with complaints of right upper abdominal pain, and the patient may have no pelvic complaints. The diagnosis can be missed if the pelvic examination is not performed, especially as transaminases and other liver function tests are generally not elevated in this condition.

The digital rectal examination is helpful in assessing for a positive stool guaiac, melena, or hematochezia, and it may also aid in the diagnosis of prostate disease, perirectal disease, and rectal foreign bodies. A testicular examination should be performed to assess for torsion, epididymitis, or masses.

Patients with abdominal pain may remain in the ED for hours during their evaluation and workup. Repeat abdominal examination is very useful in these patients as changes over time may clarify the cause of their illness.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain is extensive and includes both intra-abdominal and extra-abdominal sources of pain (Tables 7.1 and 7.2). A thorough history and physical examination are crucial in determining the etiology of the pain and narrowing down this vast list of possible causes.

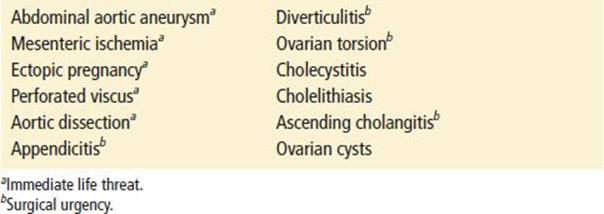

TABLE 7.1

Surgical Causes of Abdominal Pain

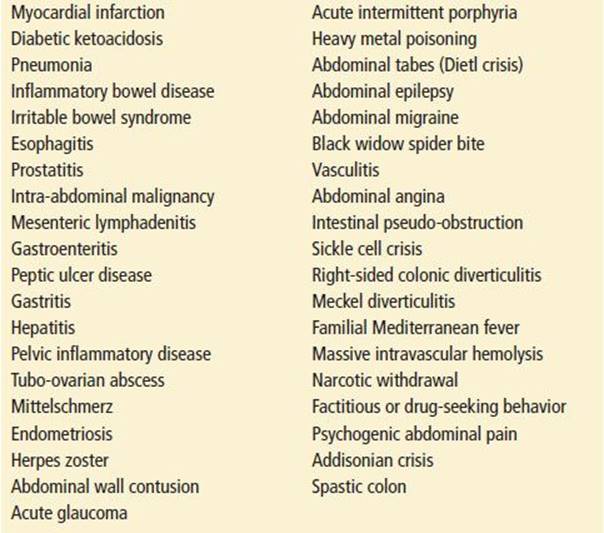

TABLE 7.2

Nonsurgical Causes of Abdominal Pain

It is of utmost importance to rule out the immediately life-threatening causes of abdominal pain. These include immediate life threats such as ruptured or leaking abdominal aortic aneurysm, splenic rupture, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, and myocardial infarction and potential life threats, including perforated viscus, intestinal obstruction, mesenteric ischemia, and pancreatitis. Once the life threat is ruled out, focus should be placed on diagnosing emergent surgical entities such as testicular and ovarian torsion, incarcerated hernia, ascending cholangitis, appendicitis, cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis, and diverticulitis.

Although many causes of abdominal pain originate from the abdominal organs, extra-abdominal causes of abdominal pain also occur. Upper abdominal pain may have a pulmonary etiology such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, or pulmonary embolism or a cardiac etiology such as myocardial infarction. Lower abdominal pain may be of genitourinary or pelvic origin.

Certain groups of patients presenting with abdominal pain deserve special attention because of their higher rates of misdiagnosis and increased morbidity and mortality. These groups include the elderly patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, women of childbearing age, and the very young. The pediatric patient with abdominal pain is discussed in Chapter 228, Abdominal Pain.”

Abdominal Pain in the Elderly

The conditions causing abdominal pain in elderly patients are usually more serious and urgent, but despite this they may present with a relatively benign history and physical examination. Of patients older than age 60 who present to the ED with abdominal pain, nearly 60% are admitted, 18% go directly to the operating room or have an invasive procedure, and 5% die within 2 weeks of presentation (3). The elderly often have comorbid illnesses confusing the clinical situation and may have hearing loss or underlying dementia or aphasia, making obtaining an adequate history more difficult. Elderly patients may be unable to physiologically mount the typical response to pain and infection. They may lack fevers despite surgical disease, and laboratory values may be normal. As the risk of mortality in patients presenting with abdominal pain increases with each decade of life, the clinician’s suspicion for a serious disease must be higher in elderly patients. The spectrum of disease is also different in elderly patients, with surgical causes accounting for more than half of the cases in patients presenting to the ED and nonspecific abdominal pain accounting for only 15% of cases (3). Elderly patients are also at increased risk for abdominal catastrophes such as mesenteric ischemia, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and intestinal volvulus. Further adding to the diagnostic difficulty, elderly patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome are much more likely to present with atypical symptoms such as shortness of breath, generalized fatigue, and abdominal pain.

Abdominal Pain in Patients with HIV

HIV-positive patients with abdominal pain are at risk for unusual conditions related to their immunocompromised state, the associated disease processes, and the side effects caused by the antiretroviral medications. In the HIV-positive patient with abdominal pain, the pain is attributable to the immunocompromised state or medications in 65% of cases (4); the three most common disorders are GI non-Hodgkin lymphoma, pancreatitis, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) enterocolitis. The latter may be life threatening, as it can cause a toxic megacolon and colonic perforation. Drug-induced pancreatitis may be fulminant and has a mortality rate of approximately 10% (4). This is most often associated with didanosine but is also reported with the use of lamivudine (especially in children), zalcitabine, or stavudine. In the immunocompromised patient it is essential to rule out infectious and surgical causes of abdominal pain before attributing it to a medication side effect (see Chapter 191).

Women of Childbearing Age

Women of childbearing age presenting with abdominal pain are often among the most challenging patients. A pregnancy test is of utmost importance for women early in their pregnancy or for any sexually active woman of childbearing age presenting with abdominal pain, as a positive result raises the possibility of ruptured ectopic pregnancy. The differential diagnosis of abdominal pain in this group is broadened by a number of possible genitourinary and pelvic pathology (ovarian torsion, ovarian cysts, ruptured ovarian cyst, mittelschmerz, pelvic inflammatory disease, and ectopic pregnancy), complicating the diagnostic workup and potentially leading to misdiagnosis. The difficulty in accurately diagnosing these patients is underscored by the fact that up to one-third of nonpregnant women of childbearing age with appendicitis are initially misdiagnosed (5).

In pregnant women, the gravid uterus becomes an intra-abdominal organ later in pregnancy and may shift the anatomic location of other organs, resulting in confusing presentations. By the second half of pregnancy, in some patients the appendix has moved out of the right lower quadrant, so appendicitis may present with tenderness ranging anywhere from the right lower quadrant, the midabdomen, the right flank, or even under the ribs. For more information on abdominal pain and pelvic pain in women of childbearing age, see Chapter 129, “Pelvic Pain.”

Many of the more common causes of abdominal pain are covered in separate chapters in this book. In addition, several other causes of abdominal pain deserve special mention.

Porphyria

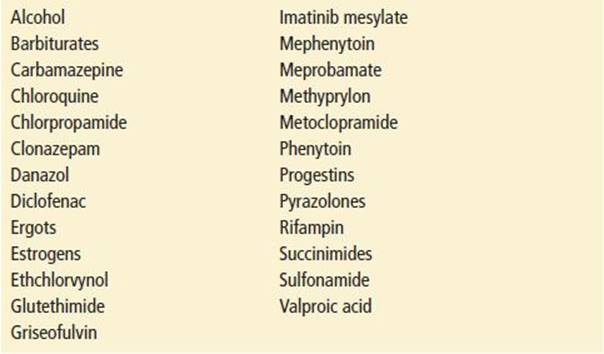

The porphyrias affect the biosynthesis of heme and result in the accumulation of excessive porphyrins and their precursors. They are inherited enzyme disorders, almost always autosomal dominant with poor penetrance. They are characterized by abdominal pain with or without manifestations of autonomic dysfunction or neuropsychiatric symptoms. Other presenting conditions in patients with porphyria include demyelinating syndromes, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, hypertensive crisis, and acute psychosis. There are many variants depending on the particular enzyme deficiency and the heme precursor that accumulates. The most common porphyria that causes abdominal pain is acute intermittent porphyria. Many drugs can precipitate attacks; a partial list is in Table 7.3.

TABLE 7.3

Drugs that May Precipitate Attacks of Acute Porphyria

The diagnosis is difficult, given the low prevalence. The pain of porphyria is usually out of proportion to physical signs, and fever is usually absent. A family history is helpful but not always present. Although not totally sensitive or specific, a Watson–Schwartz urine test should be ordered to look for porphobilinogen. The urine dipstick for urobilinogen yields a strong false-positive result. The diagnosis is made by a finding of elevated 24-hour levels of urine and stool porphyrins.

Abdominal Vasculitis

Abdominal vasculitis occurs in several disease processes, but polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura are among the most common. The spectrum of presentation varies from acute severe ischemia to mild pain, malabsorption, and abdominal angina.

Patients with abdominal vasculitis may have peripheral manifestations as well. The abdominal pain may be epigastric or periumbilical, reflecting ischemia of the foregut or midgut, respectively. Fever is prominent in some cases. The key issue in these cases is to consider the diagnosis in the first place, and then to obtain the appropriate tests, such as angiography. Abdominal vasculitis should always be considered in patients with abdominal pain who also have a history of rheumatologic disease.

Angioedema

Hereditary angioneurotic edema is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait. Symptomatic patients have low levels of C1′ esterase inhibitor (type 1), or they have a dysfunctional inhibitor (type 2); either condition allows activation of the complement system. Initial symptoms usually arise in adolescence but can have their onset in later life.

Classically, patients with angioedema do not have urticaria. Angioneurotic edema of the skin involves the deeper portions of the dermis and the subcutaneous layers as well and does not cause pruritus, whereas urticaria results from edema in the superficial layers of the skin and is pruritic.

Attacks of hereditary angioneurotic edema may begin with abdominal pain due to angioedema of the bowel wall. The pain is often colicky and is associated with nausea and vomiting, but there are scant physical findings in the abdomen. Fever is usually absent, and white blood cell counts are normal. During an attack, serum levels of C2 and C4 are low. Between attacks, the diagnosis can be established by assaying for the presence of the C1′ esterase inhibitor. Attacks of angioedema are self-limited but generally last 24 to 72 hours.

Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) has also been associated with angioedema of the small bowel. Strong consideration should be given to withholding ACE inhibitors in patients with persistent, unexplained abdominal pain. See Chapter 176, “Angioedema.”

Sickle Cell Disease

Patients with sickle cell disease and vasoocclusive painful crisis can present with pain almost anywhere in the body, including the abdomen. What is not commonly appreciated is that a few patients with homozygous sickle cell disease have their first painful crisis in their late teens or early 20s, frequently presenting with cryptogenic abdominal pain. Patients with established sickle cell disease can also pose a diagnostic challenge because their abdominal pain can be caused by a vasoocclusive event involving any of the abdominal viscera or the abdominal wall.

In addition, almost all patients with sickle cell disease have gallstones; acute cholecystitis, common duct obstruction, and ascending cholangitis are ever-present dangers in these immunocompromised patients. Abdominal pain also can develop for reasons unrelated to sickle cell disease, but the primary process may be misdiagnosed as crisis pain.

The laboratory evaluation of sickle cell patients with abdominal pain is often misleading. Many vasoocclusive crises are not associated with fever, and the white blood cell count is typically chronically elevated in these patients, commonly with a left shift. In addition, many sickle cell disease patients may be icteric because of chronic hemolysis. Many have intrinsic liver disease as well, but liver function test abnormalities are not helpful unless there is a significant deviation from baseline values. For patients presenting with RUQ pain, diagnosis can be assisted by the use of abdominal ultrasonography, nuclear scans of the biliary system, or abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning. See Chapter 199, “Sickle Cell Disease.”

Chronic Lead Intoxication

Chronic lead intoxication can present as a painful abdominal crisis (lead colic). Abdominal pain can be slowly progressive or subacute in onset. There is abdominal tenderness with voluntary guarding, but true peritoneal findings are rare. Patients commonly complain of fatigue, weakness, musculoskeletal pains, irritability, and constipation. Anemia is usually evident, and the red blood cells show basophilic stippling. An occasional patient may have the triad of lead nephropathy, “saturnine” gout, and hypertension. The diagnosis is made by determining blood lead and erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels.

Addison Disease

Although rare, Addison disease can present as a dramatic acute syndrome with vasomotor collapse, altered mental status, and characteristic electrolyte abnormalities. A subacute-to-chronic form of the disease, however, can present with recurrent abdominal pain, often associated with nausea and vomiting and usually with a negative abdominal examination. Other presenting complaints include salt craving, anorexia, weight loss, and generalized weakness. Characteristic physical findings include orthostatic hypotension, freckling and hyperpigmentation of the skin, and surgical scars. Classic laboratory findings include hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, mild azotemia, mild metabolic acidosis, and hypoglycemia.

The most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency is idiopathic or autoimmune destruction of the gland. Patients with AIDS have a high incidence of adrenal gland involvement from a number of mechanisms. See Chapter 209, “Adrenal and Pituitary Disorders.”

Opioid Withdrawal

Opioid withdrawal frequently produces crampy abdominal pain, often associated with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Diagnosis of this syndrome is frequently difficult unless the patient admits to narcotic addiction. Other signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal (e.g., mydriasis, rhinorrhea, and piloerection) may be present, but these features are rarely prominent.

Psychogenic Abdominal Pain

Psychogenic abdominal pain involves a diverse group of psychiatric disturbances, including somatoform disorders, eating disorders, conversion reactions, depression, Munchausen disorder, and hypochondriacal neurosis. Abdominal pain can also occur as a somatic delusion or as a hallucinatory phenomenon, but it generally is found in association with bizarre symptoms and evidence of underlying thought disorder. Women represent a disproportionately large percentage of patients with psychogenic abdominal pain. Early psychiatric consultation is important, but it must be kept in mind that psychogenic abdominal pain must always remain, to some degree, a diagnosis of exclusion.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Appropriate laboratory and imaging tests should be ordered in the context of the history and physical examination.

Laboratory Testing

Women of childbearing age should have a pregnancy test; sensitive and rapid bedside urine pregnancy tests can be used. A positive pregnancy test in a patient with abdominal pain should raise the concern for an ectopic pregnancy.

A complete blood count, although frequently ordered, should be interpreted with caution. A normal white blood cell count should not be used to rule out appendicitis, an elevated white blood cell count is not specific to the diagnosis, and even serial white blood cell counts may not aid in making the diagnosis. Although low hemoglobin suggests occult blood loss, it may be normal initially in rapid, acute blood loss.

Like the complete blood count, the urinalysis, although often indicated in the workup, should also be interpreted with caution. Any inflammatory process adjacent to the ureters (such as appendicitis) can cause a positive urinalysis in the absence of a urinary tract infection. Hematuria may be due to a urinary tract infection, nephrolithiasis, trauma, tumor, or an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Hematuria in patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm may be misleading and can delay the diagnosis while a urinary workup is performed. Therefore, a patient with risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm who presents with flank or abdominal pain and hematuria should be evaluated for an aneurysm as well as for urinary tract disease. If there is concern that the patient may become hemodynamically unstable, a rapid bedside ultrasound should be performed to assess for the aneurysm. If there is little concern that the patient may become unstable, then the abdominal CT can assess for both conditions.

The measurement of serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine) is helpful in determining hydration status, in guiding volume replacement, and in diagnosing metabolic disturbances. The creatinine is necessary to assess renal function and to determine whether a patient can receive IV contrast for imaging. Assessing the blood glucose may help diagnose new onset or poorly controlled diabetes. Diabetic ketoacidosis can present with abdominal pain and nausea and vomiting.

A lipase should be ordered when pancreatitis is suspected. Lipase is a more sensitive and specific indicator of pancreatitis than amylase, and an elevation of three times the normal value of the lipase is suggestive of pancreatic inflammation. Less sensitive and specific than lipase, amylase levels may be elevated in many disease processes including peptic ulcer disease, small-bowel obstruction or ischemia, common duct stone, ectopic pregnancy, renal failure, alcohol intoxication, or facial trauma (salivary amylase).

Serum transaminases, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and coagulation studies are often ordered in certain patients with a tender RUQ or symptoms suggestive of biliary or liver disease. However, these studies are of little to no clinical utility for making the diagnosis of biliary colic or cholecystitis. Thus, if biliary colic or cholecystitis is suspected, an ultrasound should be performed to make the diagnosis (6).

Other studies may be useful when specific diagnoses are considered. For instance, the serum lactate may be elevated in patients with mesenteric ischemia, although this is generally a late finding, and a normal lactate should not be used to exclude the diagnosis in a patient with a concerning history or examination.

Radiographic Studies

Plain films are primarily useful when certain disease processes are suspected: obstruction, perforation, and foreign body. The acute abdominal series includes supine and upright views of the abdomen and a single upright chest view. Of these three views, the upright chest x-ray is the single most useful view to assess for free air, although free air may be absent on plain films in as many as one-half of patients with visceral perforation. If the patient is unable to stand upright, a left lateral decubitus film can be obtained to look for air–fluid levels and free air. When perforation is suspected and plain films are negative, abdominal CT scanning is a more accurate way to make the diagnosis. The chest x-ray can also help to diagnose pneumonia, pleural effusions, or other pulmonary causes of abdominal pain. The kidney, ureter, and bladder film in combination with ultrasound may be helpful in evaluating urinary stone disease, but this approach is less sensitive than helical CT.

Ultrasound can be used to image intra-abdominal organs such as the liver, spleen, pancreas, gallbladder, kidneys, uterus, and ovaries. It is the imaging modality of choice in the patient with RUQ pain or presumed pelvic pathology. Other conditions that ultrasound can detect include aortic aneurysm, pancreatic pseudocyst, and ureteral obstruction. Transvaginal ultrasound can help determine intrauterine versus ectopic pregnancy and other pelvic pathology. Appendicitis can be diagnosed with good accuracy in the hands of an experienced ultrasonographer, though its utility decreases in patients with a large body habitus and CT remains the modality of choice in making this diagnosis unless radiation is a concern (e.g., children and pregnant women). In many hospitals, emergency physicians perform goal-oriented ultrasonography in an attempt to reduce time to diagnosis and improve patient care for patients with abdominal pain. Emergency physicians can accurately diagnose cholelithiasis (7), as well as ectopic pregnancy, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and hydronephrosis as an indicator of ureteral colic.

CT has become a mainstay in diagnosing many diseases presenting with abdominal pain. Helical CT can identify kidney stones, abdominal aortic aneurysm, appendicitis, diverticulitis, splenic or liver lacerations or infarctions, intra-abdominal abscesses, bowel obstruction, and free air. Although many of these diagnoses can be made without using contrast, IV contrast is helpful for detecting mesenteric ischemia and oral contrast for diagnosing intra-abdominal abscesses. In patients with adequate body fat stores, the stranding associated with appendicits is usually easily seen without oral contrast. However, in patients with little body fat, oral contrast may be necessary to increase the accuracy of CT in making this diagnosis. In stable patients with suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm, CT without oral or IV contrast should be performed, as it is a fast, accurate method of identifying the pathology. Such patients can be transported to the radiology suite without waiting for the creatinine to return or oral contrast to be administered. In addition, CT to diagnose ureteral stone does not require contrast administration. CT is now considered the imaging procedure of choice for patients with suspected mesenteric ischemia (8). Although angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing thromboembolism, it is an invasive, time-consuming, potentially nephrotoxic, and costly procedure and should be performed only when acute mesenteric ischemia cannot be established by noninvasive modalities (8). It should be emphasized that although modern CT scans are increasingly sensitive, they may still be falsely negative in a significant minority of patients, and their results should not be used to trump physician judgment in cases where there is a high degree of suspicion for infectious or surgical pathology.

Patients presenting with epigastric pain and a nontender abdomen who are older than the age of 50 or have cardiac risk factors should have an electrocardiogram. In addition, unstable patients and the elderly should have an electrocardiogram as part of their workup for abdominal pain. Relief of pain after “GI cocktail” does not preclude myocardial ischemia and should not be used to rule out cardiac disease.

CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS

In patients presenting with acute abdominal pain the major goals are as follows:

• Stabilize the patient, replenish volume loss, and transfuse if necessary

• Treat the pain and control emesis

• Treat the pain

• Administer antibiotics when indicated

• Obtain surgical or obstetric consultation if necessary

If ruptured ectopic pregnancy is suspected:

• Emergent gynecology consultation should be obtained.

• If available, a bedside FAST ultrasound should be performed to look for free fluid in the abdomen.

• A blood type should be drawn and at least two large-bore IVs should be started.

In the hemodynamically unstable patient, life-threatening conditions should be rapidly ruled out.

• These include ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, myocardial infarction, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, adrenal insufficiency, perforated viscus, mesenteric ischemia, and sepsis.

Immediate resuscitation should start with the airway, breathing, and circulation first.

• This includes supplemental oxygen, IV access with two large-bore IVs and continuous cardiac monitoring.

• Volume resuscitation should begin with crystalloid infusion and then packed red blood cell transfusion if bleeding is suspected.

• If the patient remains hypotensive, vasopressors may be necessary.

In the hypotensive patient who does not respond to volume replacement, acute adrenal crisis may be the cause. If adrenal insufficiency is suspected:

• A stress dose of IV steroids (hydrocortisone 100 mg or dexamethasone 10 mg) should be administered; dexamethasone may be preferable, as using it will not interfere with diagnostic testing for adrenal insufficiency.

Medications are indicated to treat pain and nausea and vomiting.

• Multiple studies have shown that treating undifferentiated abdominal pain with judicious amounts of narcotic analgesia does not affect diagnostic accuracy.

• Morphine in 2- to 5-mg increments or fentanyl in 50- to 100-μg increments can be titrated to the desired effect.

When infections are a consideration, appropriate antibiotics should be initiated early.

• If sepsis from an undifferentiated abdominal source is a concern, then broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started, covering gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria.

Management of porphyria is largely supportive.

• IV glucose infusion may abort attacks.

• IV hematin also may be helpful, although its efficacy has not been proven (2).

In patients with angioedema, because the upper airway can be involved acutely, a major clinical concern is sudden upper airway obstruction:

• Management may call for epinephrine administration, intubation, or cricothyrotomy.

• Treatment is otherwise supportive.

DISPOSITION

Patients with surgical or gynecologic disease should be evaluated by a surgeon or gynecologist and may require admission for treatment and operative intervention. The more challenging dispositions arise in patients with abdominal pain of unclear etiology. If possible, it is prudent to observe these patients for 6 to 12 hours before discharge, particularly if they are elderly. Observation may be helpful in differentiating surgical from nonsurgical disease. Patients with abdominal pain of uncertain cause that improves while in the ED can be discharged to home with close follow-up. In these patients, the most accurate and appropriate discharge diagnosis is abdominal pain of unclear etiology; it is important to resist labeling these patients with a more specific and sometimes speculative diagnosis.

Common Pitfalls

• Failure to obtain a thorough and accurate history and physical examination.

• Failure to diagnose an abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients who present with flank pain and hematuria.

• Failure to order a pregnancy test in all women of childbearing age to rule out the possibility of ectopic pregnancy.

• Relying on a normal white blood cell count to rule out the diagnosis of appendicitis or other infectious causes of abdominal pain, particularly in the elderly.

• Failure to recognize that the urinalysis may be abnormal in patients with processes that inflame the ureters, such as appendicitis or salpingitis.

REFERENCES

1. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. 2010. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/ervisits.htm. Accessed on April 29, 2014.

2. Angenete E, Jacobsson A, Gellerstedt M, et al. Effect of laparoscopy on the risk of small-bowel obstruction: A population-based register study. Arch Surg. 2012;147(4):359–365.

3. Lewis LM, Banet GA, Blanda M, et al. Etiology and clinical course of abdominal pain in senior patients: A prospective, multicenter study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(8):1071–1076.

4. Parente F, Cernushi M, Antinoti S, et al. Severe abdominal pain in patients with AIDS: Frequency, clinical aspects, causes and outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:511–515.

5. Rothrock SG, Green SM, Dobson M, et al. Misdiagnosis of appendicitis in nonpregnant women of childbearing age. J Emerg Med. 1995;13:1–8.

6. Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski N, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA. 2003;289(1):80–86. Review. Erratum: JAMA. 2009;302(7):739.

7. Kendall JL, Shimp RJ. Performance and interpretation of focused right upper quadrant ultrasound by emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2001;21(1):7–13.

8. Kim AY, Ha HK. Evaluation of suspected mesenteric ischemia: Efficacy of radiologic studies. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:327–342.