HEART FAILURE

Definition

Abnormality of cardiac structure and/or function resulting in clinical symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, fatigue) and signs (e.g., edema, rales), hospitalizations, poor quality of life, and shortened survival. It is important to identify the underlying nature of the cardiac disease and the factors that precipitate acute CHF.

Underlying Cardiac Disease

Includes (1) states that depress systolic ventricular function and ejection fraction (coronary artery disease, hypertension, dilated cardiomyopathy, valvular disease, congenital heart disease); and (2) states of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (e.g., restrictive cardiomyopathies, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, fibrosis, endomyocardial disorders), also termed diastolic failure.

Acute Precipitating Factors

Include (1) excessive Na+ intake, (2) noncompliance with heart failure medications, (3) acute MI (may be silent), (4) exacerbation of hypertension, (5) acute arrhythmias, (6) infections and/or fever, (7) pulmonary embolism, (8) anemia, (9) thyrotoxicosis, (10) pregnancy, (11) acute myocarditis or infective endocarditis, and (12) certain drugs (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, verapamil).

Symptoms

Due to inadequate perfusion of peripheral tissues (fatigue, dyspnea) and elevated intracardiac filling pressures (orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, peripheral edema).

Physical Examination

Jugular venous distention, S3, pulmonary congestion (rales, dullness over pleural effusion), peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and ascites. Sinus tachycardia is common.

In pts with diastolic dysfunction, an S4 is often present.

Laboratory

CXR may reveal cardiomegaly, pulmonary vascular redistribution, Kerley B lines, pleural effusions. Left ventricular contraction and diastolic dysfunction can be assessed by echocardiography with Doppler. In addition, echo can identify underlying valvular, pericardial, or congenital heart disease, as well as regional wall motion abnormalities typical of coronary artery disease. Measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP differentiates cardiac from pulmonary causes of dyspnea (elevated in the former).

Conditions That Mimic CHF

Pulmonary Disease: Chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and asthma (Chaps. 138 and 140); assess for sputum production and abnormalities on CXR and pulmonary function tests. Other Causes of Peripheral Edema: Liver disease, varicose veins, and cyclic edema, none of which results in jugular venous distention. Edema due to renal dysfunction is often accompanied by elevated serum creatinine and abnormal urinalysis (Chap. 42).

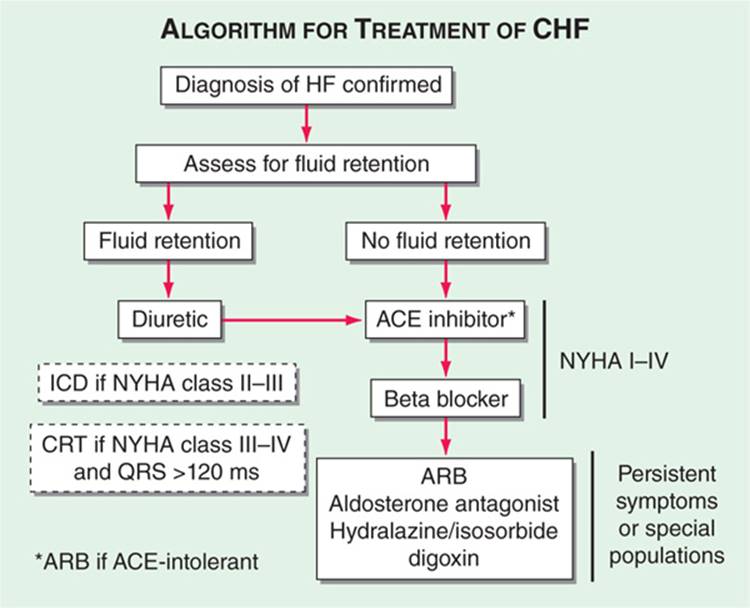

TREATMENT Heart Failure (See Fig. 133-1)

FIGURE 133-1 Treatment algorithm for chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Aimed at symptomatic relief, prevention of adverse cardiac remodeling, and prolonging survival. Overview of treatment shown in Table 133-1; notably, ACE inhibitors and beta blockers are cornerstones of therapy in pts with impaired ejection fraction (EF). Once symptoms develop:

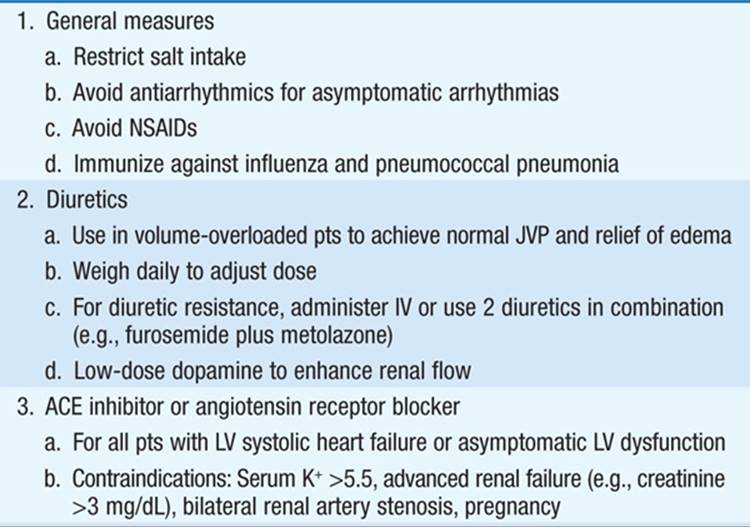

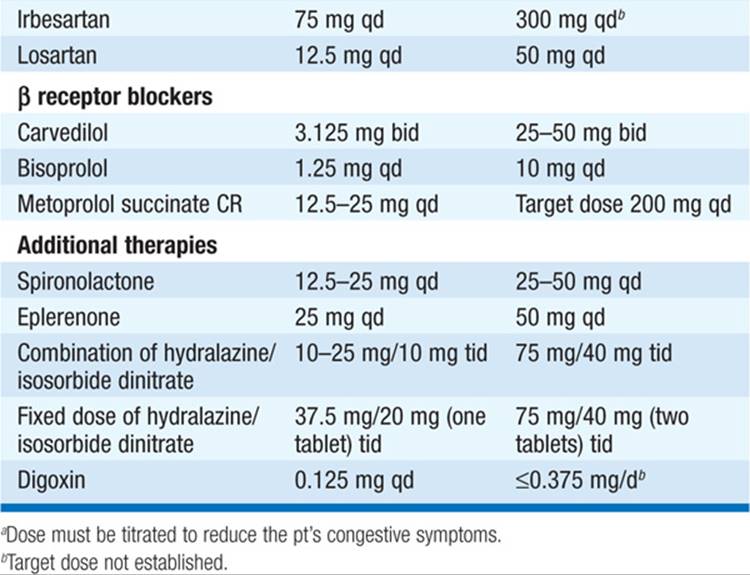

TABLE 133-1 THERAPY FOR HEART FAILURE

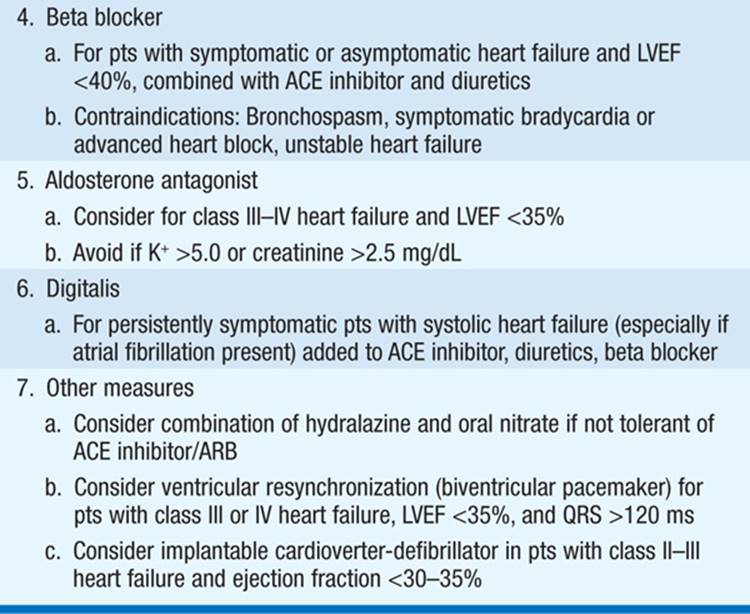

• Control excess fluid retention: (1) Dietary sodium restriction (eliminate salty foods, e.g., potato chips, canned soups, bacon, salt added at table); more stringent requirements (<2 g NaCl/d) in advanced CHF. If dilutional hyponatremia present, restrict fluid intake (<1000 mL/d). (2) Diuretics: Loop diuretics [e.g., furosemide or torsemide (Table 133-2)] are most potent and, unlike thiazides, remain effective when GFR <25 mL/min. Combine loop diuretic with thiazide or metolazone for augmented effect.

TABLE 133-2 DRUGS FOR THE TREATMENT OF CHRONIC HEART FAILURE (EF <40%)

During diuresis, obtain daily weights, aiming for loss of 1–1.5 kg/d.

• ACE inhibitors (Table 133-2): Recommended as standard initial CHF therapy. They have been shown to prolong life in pts with symptomatic CHF. ACE inhibitors have also been shown to delay the onset of CHF in pts with asymptomatic LV dysfunction and to lower mortality when begun soon after acute MI. ACE inhibitors may result in significant hypotension in pts who are volume depleted, so start at lowest dosage (e.g., captopril 6.25 mg PO tid). ARBs (Table 133-2) may be substituted if pt is intolerant of ACE inhibitor (e.g., because of cough or angioedema). Consider hydralazine plus an oral nitrate instead in pts who develop hyperkalemia or renal insufficiency on ACE inhibitor.

• Beta blockers (Table 133-2) administered in gradually augmented dosage improve symptoms and prolong survival in pts with heart failure and reduced EF <40%. After pt stabilized on ACE inhibitor and diuretic, begin at low dosage and increase gradually [e.g., carvedilol 3.125 mg bid, double q2weeks as tolerated to maximum of 25 mg bid (for weight <85 kg) or 50 mg bid (weight >85 kg)].

• Aldosterone antagonist therapy (spironolactone or eplerenone [Table 133-2]), added to standard therapy in pts with advanced heart failure reduces mortality. The diuretic properties may also be symptomatically beneficial, and such therapy should be considered in pts with class III/IV heart failure symptoms and LVEF <35%. Should be used cautiously when combined with ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) to avoid hyperkalemia.

• Digoxin is useful in heart failure due to (1) marked systolic dysfunction (LV dilatation, low EF, S3) and (2) heart failure with atrial fibrillation (AF) and rapid ventricular rates. Unlike ACE inhibitors and beta blockers, digoxin does not prolong survival in heart failure pts but reduces hospitalizations. Not indicated in CHF due to pericardial disease, restrictive cardiomyopathy, or mitral stenosis (unless AF is present). Digoxin is contraindicated in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and in pts with AV conduction blocks.

– Digoxin dosing (0.125–0.25 mg qd) depends on age, weight, and renal function and can be guided by measurement of serum digoxin level (maintain level <1.0 ng/mL).

– Digitalis toxicity may be precipitated by hypokalemia, hypoxemia, hypercalcemia, hypomagnesemia, hypothyroidism, or myocardial ischemia. Early signs of toxicity include anorexia, nausea, and lethargy. Cardiac toxicityincludes ventricular extrasystoles and ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation; atrial tachycardia with block; sinus arrest and sinoatrial block; all degrees of AV block. Chronic digitalis intoxication may cause cachexia, gynecomastia, “yellow” vision, or confusion. At first sign of digitalis toxicity, discontinue the drug; maintain serum K+ concentration between 4.0 and 5.0 mmol/L. Bradyarrhythmias and AV block may respond to atropine (0.6 mg IV); otherwise, a temporary pacemaker may be required. Antidigoxin antibodies are available for massive overdose.

• The combination of the oral vasodilators hydralazine (10–75 mg tid) and isosorbide dinitrate (10–40 mg tid) may be of benefit for chronic administration in pts intolerant of ACE inhibitors and ARBs and is also beneficial as part of standard therapy, along with ACE inhibitor and beta blocker, in African Americans with class II–IV heart failure.

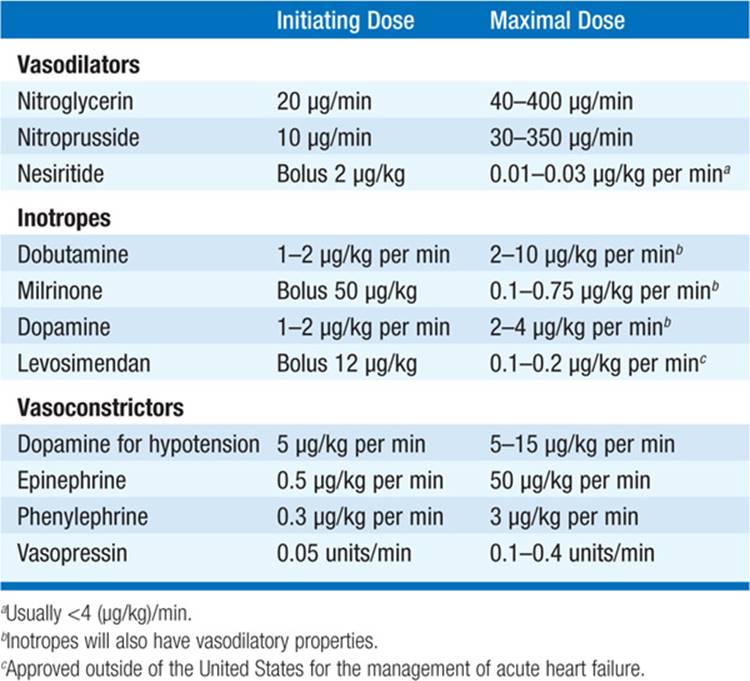

• In sicker, hospitalized pts, IV vasodilator therapy (Table 133-3) is often necessary. Nitroprusside is a potent mixed vasodilator for pts with markedly elevated systemic vascular resistance. It is metabolized to thiocyanate, which is excreted via the kidneys. To avoid thiocyanate toxicity (seizures, altered mental status, nausea), follow thiocyanate levels in pts with renal dysfunction or if administered for >2 days. IV nesiritide (Table 133-3), a purified preparation of BNP, is a vasodilator that reduces pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and dyspnea in pts with acutely decompensated CHF. It should be used only in pts with refractory heart failure.

TABLE 133-3 DRUGS FOR TREATMENT OF ACUTE HEART FAILURE

• IV inotropic agents (see Table 133-3) are administered to hospitalized pts for refractory symptoms or acute exacerbation of CHF to augment cardiac output. They are contraindicated in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Dobutamineaugments cardiac output without significant peripheral vasoconstriction or tachycardia. Dopamine at low dosage [1–5 (μg/kg)/min] facilitates diuresis; at higher dosage [5–10 (μg/kg)/min] positive inotropic effects predominate; peripheral vasoconstriction is greatest at dosage >10 (μg/kg)/min. Milrinone [0.1–0.75 (μg/kg)/min after 50-μg/kg loading dose] is a nonsympathetic positive inotrope and vasodilator. The above vasodilators and inotropic agents may be used together for additive effect.

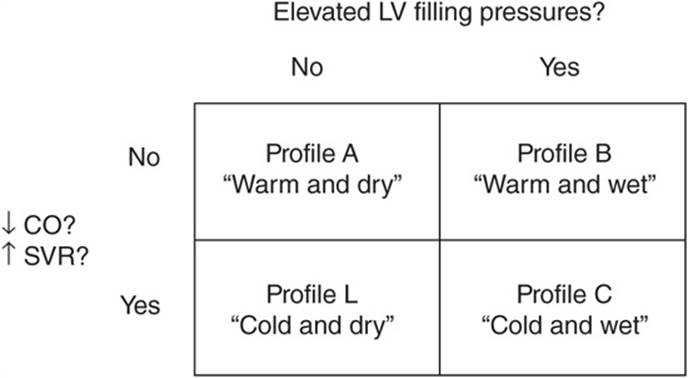

• The initial approach to treatment of acute decompensated heart failure can rely on the pt’s hemodynamic profile (Fig. 133-2) based on clinical exam and, if necessary, invasive hemodynamic monitoring: – Profile A “Warm and dry”: Symptoms due to conditions other than heart failure (e.g., acute ischemia). Treat underlying condition.

FIGURE 133-2 Hemodynamic profiles in pts with acute heart failure. CO, cardiac output; LV, left ventricular; SVR, systemic vascular resistance. (Modified from Grady et al: Circulation 102:2443, 2000.)

– Profile B “Warm and wet”: Treat with diuretic and vasodilators.

– Profile C “Cold and wet”: Treat with IV vasodilators and inotropic agents.

– Profile L “Cold and dry”: If low filling pressure (PCW <12 mmHg) confirmed, consider trial of volume repletion.

• Consider implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) prophylactically for chronic class II–III heart failure and LVEF <30–35%. Pts with an LVEF <35%, refractory CHF (NYHA class III–IV), and QRS >120 ms may be candidates for biventricular pacing (cardiac resynchronization therapy), typically in combination with an ICD. Pts with severe disease and <6 months expected survival, who meet stringent criteria, may be candidates for a ventricular assist device or cardiac transplantation.

• Pts with predominantly diastolic heart failure are treated with salt restriction and diuretics. Beta blockers and ACE inhibitors may be of benefit in blunting neurohormonal activation.

COR PULMONALE

RV enlargement resulting from primary lung disease; leads to RV hypertrophy and eventually to RV failure. Etiologies include:

• Pulmonary parenchymal or airway disease leading to hypoxemic vasoconstriction. Chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), interstitial lung diseases, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis (Chaps. 140 and 143).

• Conditions that occlude the pulmonary vasculature. Recurrent pulmonary emboli, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) (Chap. 136), vasculitis, sickle cell anemia.

• Inadequate mechanical ventilation (chronic hypoventilation). Kyphoscoliosis, neuromuscular disorders, marked obesity, sleep apnea (Chap. 146).

Symptoms

Depend on underlying disorder but include dyspnea, cough, fatigue, and sputum production (in parenchymal diseases).

Physical Examination

Tachypnea, RV impulse along left sternal border, loud P2, right-sided S4; cyanosis, clubbing are late findings. If RV failure develops, elevated jugular venous pressure, hepatomegaly with ascites, pedal edema; murmur of tricuspid regurgitation (Chap. 119) is common.

Laboratory ECG

RV hypertrophy and RA enlargement (Chap. 120); tachyarrhythmias are common.

Radiologic Studies

CXR shows RV and pulmonary artery enlargement; if PAH present, tapering of the pulmonary artery branches. Chest CT identifies emphysema, interstitial lung disease, and acute pulmonary embolism; V/Q scan is more reliable for diagnosis of chronic thromboemboli. Pulmonary function tests and ABGs characterize intrinsic pulmonary disease.

Echocardiogram

RV hypertrophy; LV function typically normal. RV systolic pressure can be estimated from Doppler measurement of tricuspid regurgitant flow. If imaging is difficult because of air in distended lungs, RV volume and wall thickness can be evaluated by MRI.

Right-Heart Catheterization

Can confirm presence of pulmonary hypertension and exclude left-heart failure as cause.

TREATMENT Cor Pulmonale

Aimed at underlying pulmonary disease and may include bronchodilators, antibiotics, oxygen administration, and noninvasive mechanical ventilation. For pts with PAH, pulmonary vasodilator therapy may be beneficial to reduce RV afterload (Chap. 136). See Chap. 142 for specific treatment of pulmonary embolism.

If RV failure is present, treat as heart failure, instituting low-sodium diet and diuretics; digoxin is of uncertain benefit and must be administered cautiously (toxicity increased due to hypoxemia, hypercapnia, acidosis). Loop diuretics must also be used with care to prevent significant metabolic alkalosis that blunts respiratory drive.

For a more detailed discussion, see Mann DL, Chakinala M: Heart Failure and Cor Pulmonale, Chap. 234, p. 1901, in HPIM-18.