Ischemic injury to the kidney depends on the rate, site, severity, and duration of vascular compromise. Manifestations range from painful infarction to acute kidney injury (AKI), impaired glomerular filtration rate (GFR), hematuria, or tubular dysfunction. Renal ischemia of any etiology may cause renin-mediated hypertension.

ACUTE OCCLUSION OF A RENAL ARTERY

Can be due to thrombosis or embolism (from valvular disease, endocarditis, mural thrombi, or atrial arrhythmias) or to intraoperative occlusion, e.g., during endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Thrombosis of Renal Arteries

Large renal infarcts cause pain, vomiting, nausea, hypertension, fever, proteinuria, hematuria, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and aspartate aminotransferase. In unilateral lesion, renal functional loss depends on contralateral function. IV pyelogram or radionuclide scan shows unilateral hypofunction; ultrasound is typically normal until scarring develops. Renal arteriography establishes diagnosis. With occlusions of large arteries, surgery may be required; anticoagulation should be used for occlusions of small arteries. Pts should be evaluated for a thrombotic diathesis, e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome. Occlusion of one or both of the renal arteries can also rarely occur in pts treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, typically in association with significant underlying renal artery stenosis.

Renal Atheroembolism

Usually arises when aortic or coronary angiography or surgery causes cholesterol embolization of small renal vessels in a pt with diffuse atherosclerosis. May also be spontaneous or associated with thrombolysis, or rarely may occur after the initiation of anticoagulation (e.g., with warfarin). Renal insufficiency may develop suddenly, a few days or weeks after a procedure or intervention, or gradually; the pace may alternatively be progressive or “stuttering,” with punctuated drops in GFR. Associated findings can include retinal ischemia with cholesterol emboli visible on funduscopic examination, pancreatitis, neurologic deficits (especially confusion), livedo reticularis, peripheral embolic phenomena (e.g., gangrenous toes with palpable pedal pulses), abdominal pain from mesenteric emboli, and hypertension (sometimes malignant). Systemic symptoms may also occur, including fever, myalgias, headache, and weight loss. Peripheral eosinophilia, eosinophiluria, and hypocomplementemia may be observed, mimicking other forms of acute and subacute renal injury. Indeed, atheroembolic renal disease is the “great imitator” of clinical nephrology, presenting in rare instances with malignant hypertension, with nephrotic syndrome, or with what looks like rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis with an “active” urinary sediment; the diagnosis is made by history, clinical findings, and/or the renal biopsy.

Renal biopsy is usually successful in detecting the cholesterol emboli in the renal microvasculature, which are seen as needle-shaped clefts after solvent fixation of the biopsy specimen; these emboli are typically associated with an exuberant intravascular inflammatory response.

There is no specific therapy, and pts have a poor overall prognosis due to the associated burden of atherosclerotic vascular disease. However, there is often a partial improvement in renal function several months after the onset of renal impairment.

RENAL VEIN THROMBOSIS

This occurs in a variety of settings, including pregnancy, oral contraceptive use, trauma, nephrotic syndrome (especially membranous nephropathy; see Chap. 152), dehydration (in infants), extrinsic compression of the renal vein (lymph nodes, aortic aneurysm, tumor), and invasion of the renal vein by renal cell carcinoma. Definitive diagnosis is established by selective renal renography. Thrombolytic therapy may be effective. Oral anticoagulants (warfarin) are usually prescribed for longer-term therapy.

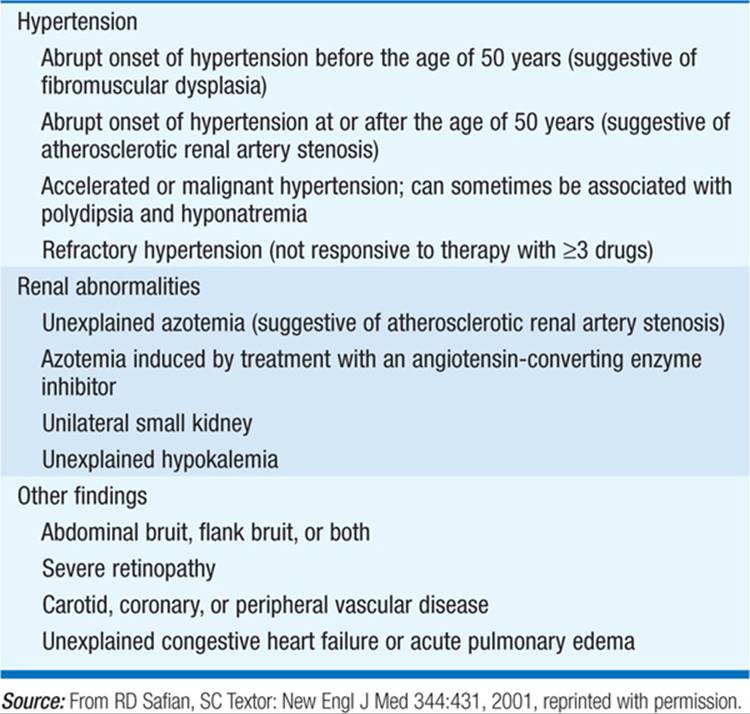

RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS AND ISCHEMIC NEPHROPATHY (SEE TABLE 155-1)

TABLE 155-1 CLINICAL FINDINGS ASSOCIATED WITH RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

Main cause of renovascular hypertension. Due to (1) atherosclerosis (two-thirds of cases; usually men age >60 years, advanced retinopathy, history or findings of generalized atherosclerosis, e.g., femoral bruits) or (2) fibromuscular dysplasia (one-third of cases; usually white women age <45 years, brief history of hypertension). Renal hypoperfusion due to renal artery stenosis (RAS) activates the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAA) axis. Suggestive clinical features include onset of hypertension <30 or >50 years of age, abdominal or femoral bruits, hypokalemic alkalosis, moderate to severe retinopathy, acute onset of hypertension or malignant hypertension, recurrent episodes of acute, otherwise unexplained pulmonary edema (typically with bilateral RAS or RAS in a solitary kidney), and hypertension resistant to medical therapy. Malignant hypertension (Chap. 126) may also be caused by renal vascular occlusion. Pts, particularly those with bilateral atherosclerotic disease, may develop chronic kidney disease (ischemic nephropathy). Although the incidence is difficult to assess, ischemic nephropathy is clearly a major cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in those over 50.

Nitroprusside, labetalol, or calcium antagonists are generally effective in lowering blood pressure (bp) acutely; inhibitors of the RAA axis (e.g., ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers) are the most effective long-term treatment.

The “gold standard” in diagnosis of renal artery stenosis is conventional arteriography. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) has been used in many centers, given the risk of radiographic contrast nephropathy in pts with renal insufficiency; however, the newly appreciated risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in pts with renal insufficiency, attributed to gadolinium-containing MRI contrast agents, has dramatically restricted this practice in most institutions. Duplex ultrasonography is an alternative, but only if experienced operators are available. In pts with normal renal function and hypertension, the captopril (or enalaprilat) renogram may be used as a screening test. Lateralization of renal function [accentuation of the difference between affected and unaffected (or “less affected”) sides] is suggestive of significant vascular disease. Test results may be falsely negative in the presence of bilateral disease.

Medical therapy is advocated for most pts with renal artery stenosis, such that investigation of suspected RAS should be reserved for those in whom an intervention is anticipated. Medical management of atherosclerotic RAS should include lifestyle modification and management of dyslipidemia (Fig. 155-1). Intervention, i.e., revascularization, should be considered in the following scenarios: (1) progressive, otherwise-unexplained reduction in GFR during treatment of systemic hypertension; (2) poorly controlled hypertension despite multiple agents at maximally tolerated dosages; (3) rapid or recurrent decline in GFR in association with reduction in systemic pressure; and/or (4) recurrent episodes of acute, otherwise unexplained pulmonary edema. Notably, pts should always be re-evaluated frequently (every 3–6 months) for the progression of RAS and the development of an indication for revascularization (Fig. 155-1).

FIGURE 155-1 Management of pts with renal artery stenosis and/or ischemic nephropathy. ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; PTRA, percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty; RAS, renal artery stenosis. [From Textor SC: Renovascular hypertension and ischemic nephropathy, in Brenner BM (ed). The Kidney, 8th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders 2008; with permission.]

The choice of nonmedical management options depends on the type of lesion (atherosclerotic vs fibromuscular), the location of the lesion (ostial vs. nonostial), localized surgical and/or interventional expertise, and the presence of other localized comorbidities (i.e., aortic aneurysm or severe aortoiliac disease). Thus fibromuscular lesions, typically located at a distance away from the renal artery ostium, are generally amenable to percutaneous angioplasty; ostial atherosclerotic lesions require stenting. Surgery is more commonly reserved for those who require aortic surgery, but it may be appropriate for those with severe bilateral disease. Again, periodic re-evaluation is needed to follow the response to intervention and, if necessary, investigate for restenosis (Fig. 155-1).

Pts who respond to vascularization will typically have a reduction in bp of 25–30 mmHg systolic, generally within the first 48 h or so after the procedure. For those with renal dysfunction, only ~25% are expected to demonstrate renal improvement, with deterioration in renal function in another 25% and stable function in ~50%. Small kidneys (<8 cm by ultrasound) are much less likely to respond favorably to revascularization.

SCLERODERMA

Scleroderma commonly affects the kidney; 52% of pts with widespread scleroderma have renal involvement. Scleroderma renal crisis can cause sudden oliguric renal failure and severe hypertension due to small-vessel occlusion in previously stable pts. Aggressive control of bp with ACE inhibitors and dialysis, if necessary, improve survival and may restore renal function.

ARTERIOLAR NEPHROSCLEROSIS

Persistent hypertension causes arteriosclerosis of the renal arterioles and loss of renal function (nephrosclerosis). “Benign” nephrosclerosis is associated with loss of cortical kidney mass and thickened afferent arterioles and mild to moderate impairment of renal function. Renal biopsy will also demonstrate glomerulosclerosis and interstitial nephritis; pts will typically exhibit moderate proteinuria, i.e., <1 g/d. Malignant nephrosclerosis is characterized by accelerated rise in bp and the clinical features of malignant hypertension, including renal failure (Chap. 126). Malignant nephrosclerosis may be seen in association with cocaine use, which also increases the risk of renal progression in pts with “benign” arteriolar nephrosclerosis.

Aggressive control of bp can usually but not always halt or reverse the deterioration of renal function, and some pts have a return of renal function to near normal. Risk factors for progressive renal injury include a history of severe, longstanding hypertension; however, African Americans are at particularly high risk of progressive renal injury (Chap. 152). The African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension (AASK) established the superiority of ACE inhibitors over beta blockers or calcium channel blockers, with respect to progression of kidney disease.

THROMBOTIC MICROANGIOPATHIES

The thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs) are classically subdivided into two general syndromes: thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). TMAs are thus broadly characterized by the presence of AKI, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neurologic dysfunction. Pts with TTP may suffer from the classic pentad of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, fever, thrombocytopenia, neurologic symptoms and signs, and renal dysfunction. Extrarenal symptoms are in contrast less prominent or common, but not unheard of, in postdiarrheal HUS.

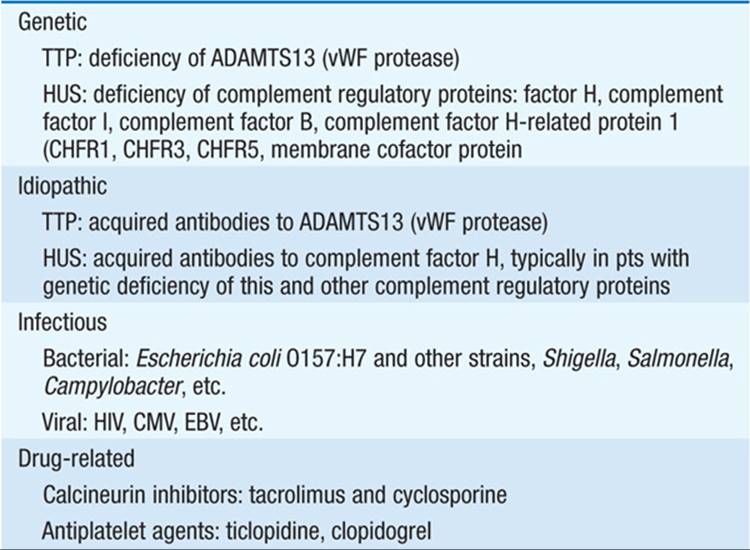

The major causes of TMA are listed in Table 155-2; the common pathogenic pathway is endothelial injury. In idiopathic and familial TTP, pts have a marked deficiency in the ADAMTS13 protease, leading to accumulation of ultra-large, unprocessed von Willebrand factor (vWF) polymers, platelet aggregation, and TMA. In contrast, postdiarrheal HUS is associated with presence of a bacterial toxin (Shiga toxin or verotoxin) that causes endothelial injury; children and the elderly are particularly susceptible. Pts with atypical or nondiarrheal HUS may in turn have inherited or acquired deficiencies in membrane-associated regulatory proteins of the alternative complement pathway, enhancing endothelial sensitivity to complement.

TABLE 155-2 CAUSES OF THROMBOTIC MICROANGIOPATHY

Laboratory evaluation will usually reveal evidence of a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, although this may be absent in certain causes, e.g., antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. The reticulocyte count should be elevated, along with an increase in the red cell distribution width. Hemolysis should increase levels of LDH and decrease circulating haptoglobin, with a negative Coombs’ test. Examination of the peripheral smear is key, since the presence of schistocytes will help establish the diagnosis. Specific diagnostic tests—e.g., HIV testing, antiphospholipid antibody screens—may be useful in the differential diagnosis. Measurement of vWF protease activity promises considerable diagnostic and therapeutic utility; however, at this point, this is not routinely available in a time frame suitable for routine clinical use. Renal biopsy will classically demonstrate fibrin- and/or vWF-positive thrombi in arterioles and glomeruli, endothelial injury, and widening of the subendothelial space leading to a “double contour” appearance of the glomerular capillaries.

Treatment of TMA depends on the underlying pathogenesis. Idiopathic TTP is due to the presence of circulating antibody inhibitors of ADAMTS13 and thus responds to plasma exchange, combining plasmapheresis (removal of antibody) and infusion of fresh-frozen plasma (repletion with native ADAMTS13/vWF protease). Pts with atypical HUS due to deficiencies in complement regulatory proteins respond to therapy with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody to C5 that prevents the production of the terminal complement components C5a and the membrane attack complex C5b-9.

TOXEMIAS OF PREGNANCY

Preeclampsia is characterized by hypertension, proteinuria, edema, consumptive coagulopathy, sodium retention, hyperuricemia, and hyperreflexia; eclampsia is the further development of seizures. Glomerular swelling and/or ischemia causes renal insufficiency. Coagulation abnormalities and AKI may occur. Treatment consists of bed rest, sedation, control of neurologic manifestations with magnesium sulfate, control of hypertension with vasodilators and other antihypertensive agents proven safe in pregnancy, and delivery of the infant.

VASCULITIS

Renal complications are frequent and severe in polyarteritis nodosa, hyper-sensitivity angiitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s), and other forms of vasculitis (Chap. 170). Therapy is directed toward the underlying disease.

SICKLE CELL NEPHROPATHY

The hypertonic and relatively hypoxic renal medulla coupled with slow blood flow in the vasa recta favors sickling. Papillary necrosis, cortical infarcts, functional tubule abnormalities (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus), glomerulopathy, nephrotic syndrome, and, rarely, ESRD may be complications.

For a more detailed discussion, see Textor SC, Leung N: Vascular Injury to the Kidney, Chap. 286, p. 2375, in HPIM-18.