George Iancu1

(1)

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Filantropia Clinical Hospital, 11-13, Blvd. Ion Mihalache, Bucharest, 71117, Romania

George Iancu

Email: klee_ro@yahoo.com

Abstract

Knowledge of female pelvic anatomy helps the clinician recognize correctly childbirth trauma and manage it accordingly. This chapter presents aspects of the anatomy of abdominal wall, external and internal genital organs, anal sphincter and pelvic muscles, including levator ani. The vulva consists of mons pubis, clitoris, hymen, labia minora and majora, vestibule and urethral meatus. The vagina is a virtual cavity between the bladder anteriorly and rectum posteriorly, a musculo-membranous organ that connects the vulva and the uterus. The muscles of the external female genitalia are formed by pelvic muscles and cavernous bodies (ischiocavernosus and bulbocavernosus). The pelvic diaphragm that supports the pelvic load is formed by the levator ani muscle (pubovaginalis, pubourethralis, puborectalis and iliococcygeus muscles) and the coccygeus muscle. The anal sphincter is formed by the external and internal anal sphincter, with different structures and function.

Keywords

AnatomyFemale genital organsPelvic diaphragmLevator ani muscleAnal sphincterPudendal nerve

Abdominal Wall

The anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall is usually described together with the anatomy of female reproductive system because of the changes in volume and shape in pregnancy and the implications of surgery of the lower abdomen. The anterior abdominal wall is divided into sections, namely from lower to upper parts – hypogastric region in the lower centre, right and left ilio-inguinal regions, umbilical region around the umbilicus, bordered laterally by right and left lumbar regions and epigastric region in the upper centre with right and left hypocondriac regions on the sides. The structure of the anterior abdominal wall is layered, consisting of skin, subcutaneous adipose tissue, muscle fascia, muscle and parietal peritoneum.

The skin is soft and elastic, loosely attached to the underlying tissue, excepting the umbilical region. The orientation of collagen fibers in the dermis forms Langer lines, arranged transversely, as are the tension forces in the abdominal skin. The importance of force distribution in the anterior abdominal wall is illustrated by the fact that vertical skin incisions usually heal with wider scars compared with transverse incisions because of the lateral tension.

Underneath the skin, the subcutaneous adipose tissue is organized into two layers: Camper’s fascia, more superficial, consisting essentially of fat tissue, and Scarpa’s fascia, placed deeper, a fibroelastic membrane attached to the fascia lata and aponeurosis in the midline.

The rectus sheath is made of strong fibrous tissue that supports the rectus and pyramidalis muscles; it also contains vessels (inferior and superior epigastric vessels) and nerves (terminal branches of lower six thoracic nerves). It is wider superiorly and attaches to the sternum, xiphoid process and lower border of the costal cartilages (seventh to ninth), while inferiorly it is narrow and attaches to the symphysis pubis. The rectus sheath is formed by the aponeuroses of transversus abdominis, internal and external oblique muscles. The internal oblique muscle aponeurosis splits in two lamellae at the lateral border of the rectus muscle cranially and remains unsplit in the lower third of the rectus aponeurosis. The cranial two-thirds of the rectus sheath are formed by anterior wall (external oblique sheath and anterior lamella of internal oblique sheath) and posterior wall (transversus abdominis sheath and posterior lamella of internal oblique sheath); for the caudal one-third, all three aponeuroses fuse anteriorly, and the posterior wall of rectus sheath is formed only by fascia transversalis. The border between the cranial two-thirds and the caudal one-third is called the arcuate line.

The blood supply consists of branches of the femoral artery and external iliac artery. The branches of the femoral artery are (from medial to lateral): superficial external pudendal artery, superficial epigastric and superficial circumflex iliac artery. They originate from the femoral artery immediately below the inguinal ligament, at the level of the femoral triangle. These branches supply the overlying skin and subcutaneous tissue; the superficial epigastric artery has a course towards the umbilicus; it is usually identified during low transverse abdominal incision procedures. The branches from external iliac artery are inferior (deep) epigastric artery and deep circumflex iliac artery; they supply the deeper layers, namely, muscles and fascia of the anterior abdominal wall. The inferior epigastric artery has a course initially lateral to the rectus muscle, then posterior, between the posterior aspect of the rectus muscle and the sheath. At the level of the umbilicus, it anastomoses with the superior epigastric artery, a branch of the internal thoracic artery. The veins follow the course of the arteries.

Innervation is provided by the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves originating inferiorly from L1 dermatome, while the superior area is supplied by the abdominal extension of the intercostal (T7-T11) and subcostal (T12) nerves.

External Genital Organs

Vulva

The vulva consists of all the visible structures from pubis to the perineal body: mons pubis, clitoris, hymen, labia minora and majora, vestibule and urethral meatus.

Labia Majora

The labia majora are anatomic structures originating in the mons pubis, consisting essentially of fat tissue, rounded in shape; they terminate posteriorly in the perineum. They correspond embryologically to the male scrotum. The round ligaments terminate in their upper extremities. The overlying skin is covered with hair laterally; it lacks hair on the inner surface. There are also numerous sweat and sebaceous glands. Their size varies with age, height, weight or parity, being approximately 7–9 cm long, 2–4 cm wide and 1–1.5 cm thick. Under the skin there is a rudimentary, poorly developed muscle layer that forms the tunica dartos labialis. The fatty labial structure is abundantly supplied with a rich venous plexus that can develop varicosities in pregnancy due to increased venous pressure. Arterial supply comes from internal and external pudendal arteries.

Labia Minora

Between the labia majora and the vaginal opening there is a pair of thin skin folds named labia minora. They are about 5 cm long, 0.5–1 cm thick and 2–3 cm wide. The labia minora extend from the base of clitoris, where they bifurcate to form the prepuce and the frenulum of the clitoris. Posteriorly, the labia minora fuse at the posterior commissure or fourchette. They consist of connective tissue, mainly elastin fibers, vessels and smooth muscle fibers and nerve endings; they do not contain fat tissue and are covered with stratified squamous epithelium on the lateral aspect and non-keratinized epithelium medially. They lack hair follicles, are smooth and pigmented and contain many sebaceous glands.

The arterial blood supply is from branches of the superficial perineal artery, branch of the dorsal artery of clitoris and the medial aspect of rete of labia majora; they drain in the venous plexus of labia majora and then in the inferior haemorrhoidal veins posteriorly and clitoral veins anteriorly. The lymphatic drainage involves the superficial and deep subinguinal nodes. Innervation is provided by the pudendal nerve through perineal nerves.

Clitoris

The clitoris is the principal erogenous female organ located between the clitoridal hood (prepuce) and external urethral meatus. It is about 2 cm in maximum length and consists of body, glans and two crura. The latter extend laterally at the anterior vulvar part. Usually the glans does not overpass 0.5 cm and is composed of erectile tissue being covered by the prepuce and containing ventrally the frenulum of the clitoris. The erectile body or corpus clitoridis consists of two corpora cavernosa; they extend laterally and form the crura, which lie beneath the ischiopubic ramus bilaterally and deep beneath the ischiocavernosus muscle.

The arterial blood supply is provided by the dorsal artery of the clitoris, terminal ramus of the internal pudendal artery. The venous drainage follows the pudendal vein pathway through pudendal plexus. The superficial inguinal ganglia receive the lymph from the clitoris. Innervation is abundant in the prepuce while it is absent within the glans.

Vestibule and Vestibular Glands

The vestibule is located between the labia minora, clitoris, external surface of the hymen and posterior commissure or fourchette. This is the level of the urethra and vaginal opening, Bartholin and Skene gland ducts. The fossa navicularis is the area between the fourchette and vaginal opening, located posteriorly. The vestibular glands are two Bartholin glands (greater vestibular glands), the paraurethral glands, the largest being Skene glands and the minor vestibular glands.

The bulbs of the vestibule are elongated masses of erectile tissue around the vaginal opening; they join each other anteriorly and end up in the clitoris. At their posterior ends lie the greater vestibular glands (Bartholin). The bulbs are covered posteriorly by the bulbocavernosus muscle.

Between the vestibule and vaginal opening lies the hymen, an elastic membrane with various shapes and openings. In postcoital state, it presents as hymenal remnants or caruncles around the vaginal opening. The external urethral meatus opens at about 2–3 cm posterior to clitoris or 1–1.5 cm below the pubic arch.

Vagina

The vagina is a virtual cavity that lies between the bladder anteriorly and rectum posteriorly. It is a musculo-membranous organ between the vulva and the uterus. The upper third of the vagina originates embryologically from the Müllerian ducts, while the lower two-thirds originate from the urogenital sinus. The vagina is separated from the bladder by the vesicovaginal septum and from the rectum by the rectovaginal septum inferiorly, while the upper vagina is separated by the Douglas cul-de-sac or the rectouterine pouch. The vaginal length varies between individuals, the posterior wall being longer than the anterior wall; consequently, the posterior vaginal cul-de-sac is deeper than the anterior one. Usually, the posterior vaginal wall is about 7–10 cm in length, while the anterior wall is 6–8 cm. The vaginal length and capacity vary with hormonal status and parity. The vaginal lining consists of non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium; the wall structure is constituted of smooth muscle and connective fibers (collagen, elastin). It does not contain any glands. Vaginal secretion is produced by transudation from the rich vascular plexus in its structure. Vascular supply is provided by the descending vaginal branches from the cervical branch of the uterine artery; it irrigates the upper vagina. The distal portion of the vagina is irrigated by branches of the internal pudendal artery. The posterior vaginal wall receives branches of the middle rectal artery. The vascular branches on one side anastomose with the contralateral vessels to form rich vascular plexuses. Lymph drains through iliac nodes (external, internal and common) for the upper third of the vagina, while the middle third drains into the internal iliac nodes and the lower third drains into the inguinal nodes.

Perineal Muscles

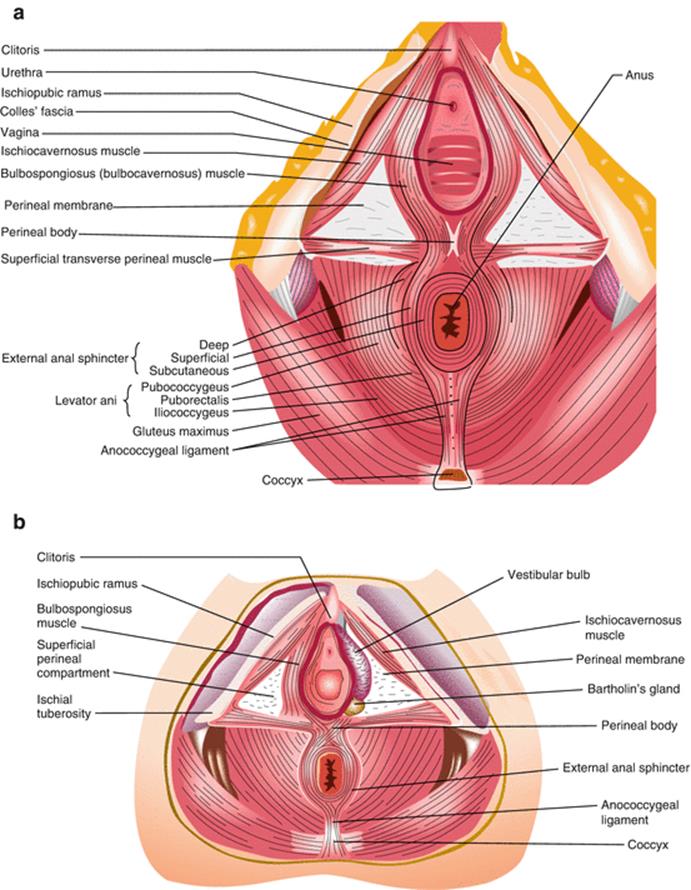

The muscles of the external female genitalia are the pelvic muscles and cavernous bodies (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1

Superficial perineal compartment (superficial transverse perineal muscles (a), vestibular and Bartholin’s gland after left bulbospongiosus muscle removal (b) (With kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media: Thakar and Fenner [5], Figure 1.2, p. 1–12)

Ischiocavernosus Muscle

The origin of ischiocavernosus muscle is, as the name suggests, at the ischial tuberosity and inferior ramus of ischium bone. Its course runs along the inferior surface of the symphysis pubis medially and terminates at the clitoridal base on the anterior surface of the symphysis. The ischiocavernosus muscle sends fibers medially around the proximal urethra to form part of the voluntary urethral sphincter. Its function is to slow venous return and maintain the clitoris erection. Vascular supply is provided by the perforating branches of the perineal artery on its course towards the clitoris. Innervation originates from the pudendal nerve.

Bulbospongiosus Muscle

The bulbospongiosus muscle originates from the central tendon of the perineum; its course runs anteriorly around the vaginal opening, covering the bulb of vestibule. It inserts into the fibrous tissue covering the corpus cavernosus of the clitoris, the fibrous tissue dorsal of the clitoris and sends fibers to the striated urethral sphincter. It contributes to clitoral erection and orgasm, and closes the vagina. Blood supply is ensured by the perineal branches of the internal pudendal artery. Lymphatic drainage is via the superficial inguinal nodes and posteriorly towards the rectal nodes.

Pelvic Floor

The pelvic diaphragm is a fibromuscular structure. It is formed by the levator ani muscle and the coccygeus muscle.

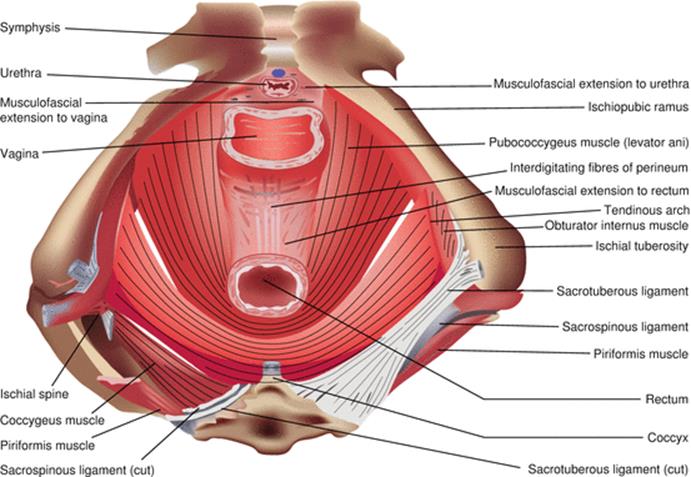

Levator Ani

The levator ani is a group of striated muscles with a very important role in pelvic organ support (Fig. 1.2). It is practically the most important supportive structure of the pelvis and forms together with its fascial structures the pelvic diaphragm. It is funnel-shaped and is covered superiorly and inferiorly by connective tissue forming the superior and inferior fasciae of the levator; it is perforated by the urethra, vagina and anal canal as they exteriorize on the perineum. The levator ani is formed by three muscles: pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus and puborectalis muscles. It is frequently damaged during childbirth, mainly with instrumental deliveries [1]. The pubococcygeus is made of puboperinealis, puboanalis and pubovaginalis muscles, according to muscle fibers’ insertion. It is named sometimes also pubovisceral muscle because of its insertion on pelvic viscera. The boundaries between levator muscle components are vague and difficult to identify anatomically. The complexity of the levator structure and function is the cause of the confusion in its description and terminology in the literature. Kearney et al. reviewed the literature regarding the origin and insertion points as well as the terminology used to describe the levator and its components (Table 1.1) [2].

Fig. 1.2

Levator ani muscle (With kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media: Thakar and Fenner [5], Figure 1.7, p. 1–12)

Table 1.1

Levator ani structure and function

|

Levator ani |

Origin |

Insertion |

Function |

|

Pubococcygeus |

|||

|

Puboperinealis |

Pubic bone |

Perineal body |

Constant tone pulls perineal body ventrally toward pubis |

|

Pubovaginalis |

Pubic bone |

Lateral vaginal wall (mid-urethral level) |

Elevates vagina in region of mid-urethra |

|

Puboanalis |

Pubic bone |

Intersphincteric groove between internal and external anal sphincter; ends in the anal skin |

Elevates the anus and the anal skin |

|

Puborectalis |

Pubic bone |

Joins contralateral fibers and forms a sling behind the rectum |

Closes pelvic floor and forms anorectal angle |

|

Iliococcygeus |

Tendinous arch of the levator ani |

The two sides fuse in the iliococcygeal raphe |

Supportive diaphragm that spans the pelvic canal |

Adapted from Kearney et al. [2]

The pubococcygeus muscle originates from the inner surface of the pubic bone; its course runs inferiorly and medially to insert into the lateral vaginal walls (pubovaginalis), perineal body (puboperinealis) and anal wall, at the line corresponding to the intersphincteric groove between the two components of anal sphincter (internal and external). The puborectalis muscle is U-shaped, surrounding the anorectal junction.

The iliococcygeus muscle originates laterally from the arcus tendineus levator ani and inner surface of the ischial spines; it forms most of the levator plate. A few fibers attach the inferior sacrum and coccyx, but most of them join the opposite fibers to form the anococcygeal raphe; the raphe continues with the anococcygeal ligament.

The role of levator ani is mainly supportive. The pubovaginalis supports the lateral vaginal walls and indirectly the urethra, participating in the continence mechanism. The puboperinealis narrows the genital hiatus drawing the perineal body towards the symphysis pubis during contraction. The puboanalis contributes to the narrowing of genital hiatus and elevates the anus. The puborectalis muscle elevates the anorectal junction and is considered part of the anal sphincteric mechanism. The iliococcygeus muscle has an important role in pelvic support, as already mentioned. The levator ani muscle has some particularities that make it different from other muscles: (1) the permanent muscle tone contributes to the normal pelvic support, except during voiding or defecation; (2) it contracts rapidly with coughing or sneezing, maintaining continence; (3) it is distended during labour and delivery, maintaining integrity in the majority of cases, and then contracts and regains normal function [3].

Coccygeus Muscle

The coccygeus muscle originates from the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament and inserts into the lateral margin of S5 vertebra and coccyx; it supports the bone and pulls it anteriorly when contracting.

Urogenital Diaphragm

While the term urogenital diaphragm has no official entry in Terminologia Anatomica, it is still used occasionally to describe the muscular components of the deep perineal pouch. According to older texts, the urogenital diaphragm comprises of the deep transverse perineal muscle and sphincter urethrae. Inferiorly and superiorly, it is covered by connective tissue that forms the fascia of the urogenital diaphragm. It strengthens the pelvic diaphragm anteriorly. The transverse perineal muscle originates from the ischial tuberosity and inferior ischial ramus; it runs transversely to insert medially into the central perineal tendon. Often, the fibers interdigitate around the central tendon with bulbospongiosus and puborectalis muscle fibers. The blood supply and innervation is provided by the pudendal bundle. The sphincter urethrae muscle originates from the medial aspect of the ischiopubic rami and inserts into the urethra and vagina. Its main role is to compress the urethra.

Internal Genital Organs

Uterus

Located in the pelvic cavity, between the bladder anteriorly and rectum posteriorly, the uterus has a fibromuscular structure; it is made of body superiorly and cervix inferiorly.

The cervix comprises of a vaginal part with a round convex surface or ectocervix covered with stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium, while the endocervical canal is lined by columnar epithelium containing mucinous glands. The endocervical canal is about 2–3 cm long; it communicates cranially with the endometrial cavity and caudally with the vagina. Of particular interest is the transformation zone or the dynamic area of squamocolumnar junction that can be the origin of cervical preinvasive and invasive neoplastic pathology. The position of the transformation zone varies depending on woman’s age and hormonal status; usually, in young women or during pregnancy, the columnar epithelium extends onto the ectocervix and forms what is known as ectopy, a condition that sometimes causes bleeding with intercourse. During menopause, the squamocolumnar junction is found usually within the endocervical canal.

The uterine body can have different shapes and anatomical position, varying with childbearing status or hormonal profile of the woman. The uterine body lies between the bladder anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly. The peritoneum forms pouches between the three organs, namely the vesicouterine and rectouterine pouches (Douglas). The shape of the uterus corresponds to a flattened pear or pyriform, the upper part being the uterine body and the lower, narrow part, the cervix. The cervix unites with the body through the isthmus that forms the lower uterine segment in pregnancy. The cranial part is the uterine fundus that ends on the sides with uterine cornua; at this level the fallopian tubes originate and run laterally towards the ovaries.

The most common uterine position is described as anteverted and flexed. Occasionally, the uterus can be retroverted or angling posteriorly. The flexion is the angle between uterine body and cervix and the version describes the angle between uterus and the upper vagina.

The uterine cavity is lined with columnar epithelium with mucous secreting glands, forming the endometrium. The cavity is triangular shaped; at this level, the fallopian tubes open through tubal orifices. The endometrium is hormonally controlled and undergoes shedding monthly during reproductive years. The endometrium covers the muscular layer of the uterine wall, the myometrium. The myometrium forms most of the uterine wall thickness, varying between 1.5 and 2.5 cm; it consists of smooth muscle fibers stratified on layers of various orientation. The interlacing muscular layers play an important role in the haemostatic mechanism during the third stage of labour. The uterus is covered by the visceral peritoneum that forms the uterine serosa, which covers the uterine body and cervix posteriorly, while the cervix anteriorly is covered by the bladder. The neuro-vascular pedicles approach the uterus laterally where the double-layered peritoneum forms the broad ligament. At the level of the uterine cornua, the fallopian tubes and the round ligaments originate, running laterally, the tubes towards the ovaries and the round ligaments towards the internal inguinal orifices; their course continues through the inguinal canal inserting into the labia majora.

Ovaries

The ovaries are the female gonadal structures, paired, lying in the lateral pelvic wall in the ovarian fossa; at this level, they are in close proximity with the ureters, internal iliac and obturator vessels and nerve and with the uterine artery at its origin. The lateral surface faces the pelvic wall, while the medial surface lies in proximity to the uterus and the broad ligament; the fallopian tube approaches the ovary with the fimbria. The ovary has an anterior border that encloses the vascular pedicle (mesovarium) towards the posterior leaf of the broad ligament and a posterior border that faces the peritoneum. The ovary attaches to the uterine cornu through the ovarian ligament, located medially and inferiorly. The ovary is supported and vascularized by the infundibulopelvic ligament, the ovarian ligament and mesovarium.

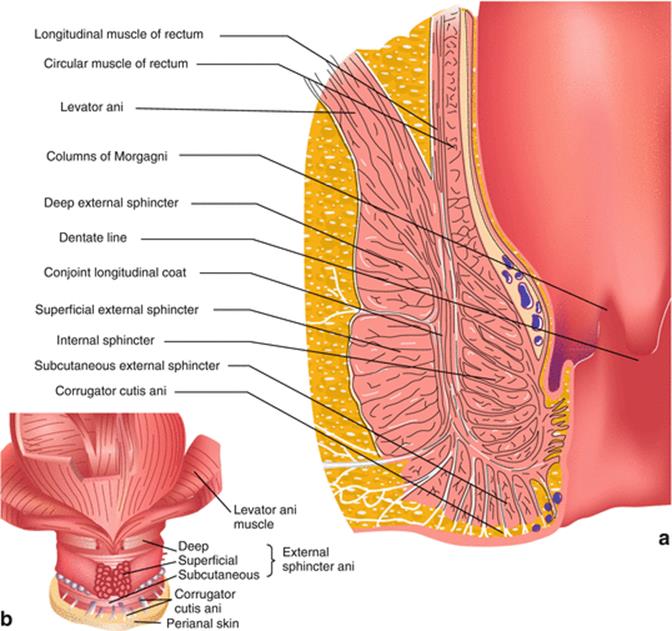

Anal Sphincter Complex

The anal sphincter is formed by two groups of muscles, the external anal sphincter and the internal anal sphincter, that differ in structure and function (Fig. 1.3).

Fig. 1.3

(a, b) Anal sphincter complex (With kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media: Thakar and Fenner [5], Figure 1.4, p. 1–12)

The external anal sphincter (EAS) consists of three parts – subcutaneous, superficial and deep. It is a striated muscle surrounding the most inferior part of the anal canal [4]. The subdivisions are difficult to identify through anatomical dissection, although information about them could be obtained using imaging studies [5]. The deepest fibers of the EAS mix to some extent with fibers of the puborectalis and transverse perineal muscles anteriorly, with no attachments posteriorly. The middle part of the EAS attaches anteriorly to the perineal body and posteriorly to the coccyx through the anococcygeal ligament. Posteriorly, some fibers of the superficial EAS attach to the anococcygeal raphe. The lowest part of the EAS surrounds the lowest part of the anal canal, with no more internal anal sphincter in between [4].

The internal anal sphincter (IAS) is a smooth muscle that is a continuation of the circular smooth muscle of the bowel. The IAS ends at 6–8 mm above the anal margin; this corresponds to the junction of the subcutaneous with superficial parts of the EAS.

Between EAS and IAS, there is a vertical muscular layer, the longitudinal anal muscle. It lies between the layers of EAS and IAS and extends along the anal canal from the anorectal junction to the perianal dermis; at this level, it terminates through seven to nine fibroelastic septa, which cross the superficial part of EAS. It consists of outer striated fibers, originating probably from the levator ani and inner smooth muscle fibers, from the rectal longitudinal muscle layer [6].

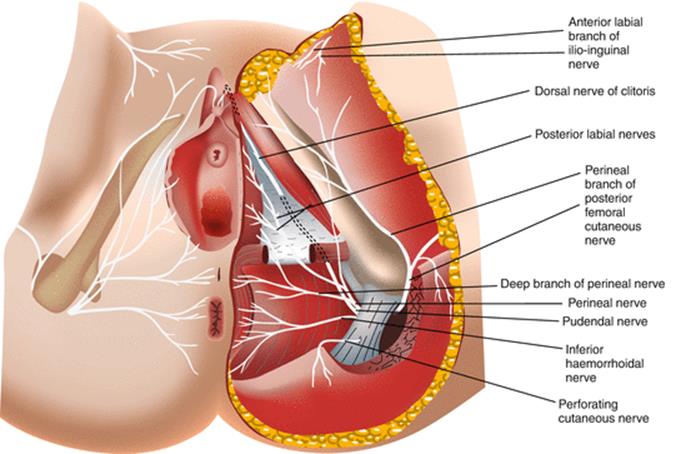

The Pudendal Nerve

The pudendal nerve is one of the major branches of the sacral plexus, together with the sciatic, superior and inferior gluteal and posterior femoral cutaneous nerves. It is the main perineal nervous structure, having sensory and motor function. It innervates the external anal sphincter (EAS), urethral sphincter, perineal musculature and perineal skin. It originates from the ventral roots of the sacral nerves between S2 and S4 and receives contributions from S1 and S5 [7]. The main branches of the pudendal nerve are inferior rectal (or anal) nerve and two terminal branches, the perineal nerve and dorsal nerve of clitoris. The inferior rectal branch originates from the pudendal nerve before it enters the pudendal canal (Alcock’s canal) and supplies the skin and muscle of the anal triangle (EAS). The perineal branch divides into smaller branches for labia majora, transverse perineal muscles, urethral sphincter and perineal skin. The dorsal nerve of the clitoris contains part of the terminal fibers of the nerve, innervating the corpus cavernosum and ending in glans clitoris.

The pudendal nerve passes between the piriformis muscle and coccygeus (ischiococcygeus) muscles and leaves the pelvis through the inferior part of the greater sciatic foramen. After crossing the ischial spine, the pudendal nerve re-enters the pelvis inferiorly through the lesser sciatic foramen and joins the internal pudendal vessels on the lateral pelvic wall at the level of ischiorectal fossa. The obturator fascia splits and generates a sheath that contains the pudendal nerve and vessels – the Alcock’s canal. The inferior rectal branch is derived from the pudendal nerve before the latter enters the canal. Rarely, the inferior rectal nerve can originate directly from the sacral plexus [8]. The terminal branches of the pudendal nerve (perineal and dorsal nerve of the clitoris) arise near the midpoint of the pudendal canal and travel together to the end of it. The perineal nerve ends as sensory and motor branches to the perineum and EAS, while the dorsal nerve of the clitoris ends as a true terminal branch at the level of clitoris and infrapubic region (Fig. 1.4). Studies on cadavers identified an additional branch of the pudendal nerve at the level of the sacrospinous ligament that innervates the perineum and levator ani muscle [8].

Fig. 1.4

Pudendal nerve – terminal branches (With kind permission from Springer Science + Business Media: Thakar and Fenner [5], Figure 1.8, p. 1–12)

References

1.

Kearney R, Miller JM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Obstetric factors associated with levator ani muscle injury after vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):144–9.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

2.

Kearney R, Sawhney R, DeLancey JO. Levator ani muscle anatomy evaluated by origin-insertion pairs. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):168–73.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

3.

Barber MD, Bremer RE, Thor KB, Dolber PC, Kuehl TJ, Coates KW. Innervation of the female levator ani muscles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(1):64–71.CrossRefPubMed

4.

Wigley C. True pelvis, pelvic floor and perineum. In: Standring S, Gray H, editors. Gray’s anatomy. The Anatomical basis of clinical practice. 40th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

5.

Thakar R, Fenner DE. Anatomy of the perineum and the anal sphincter. In: Sultan A, Thakar R, Fenner DE, editors. Perineal and anal sphincter trauma. London: Springer; 2007.

6.

Macchi V, Porzionato A, Stecco C, Vigato E, Parenti A, De Caro R. Histo-topographic study of the longitudinal anal muscle. Clin Anat. 2008;21(5):447–52. doi:10.1002/ca.20633.CrossRefPubMed

7.

Shafik A, el-Sherif M, Youssef A, Olfat ES. Surgical anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its clinical implications. Clin Anat. 1995;8(2):110–5.CrossRefPubMed

8.

Schraffordt SE, Tjandra JJ, Eizenberg N, Dwyer PL. Anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its terminal branches: a cadaver study. A N Z J Surg. 2004;74(1–2):23–6.CrossRef