NOLAN S. KARP

Gynecomastia is enlargement of the male breast and is caused by an increase in ductal tissue, stroma, and/or fat. Most frequently, the changes occur at the time of hormonal change: infancy, adolescence, and old age.

The term gynecomastia was introduced by Galen during the 2nd century AD and the surgical resection was first described by Paulis of Aegina1,2 in the 17th century AD.

ETIOLOGY

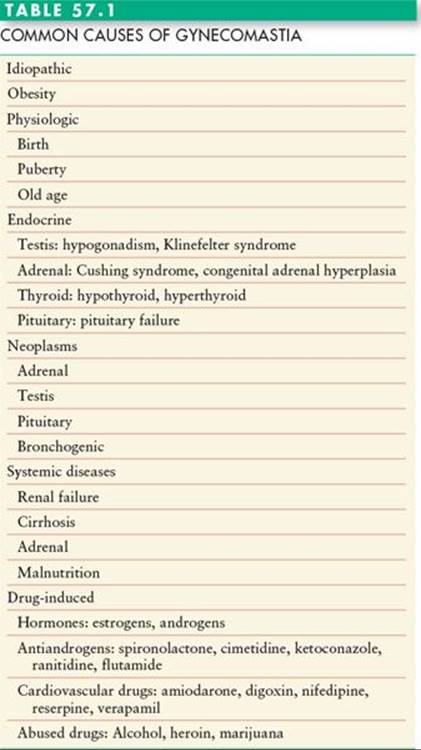

The most common cause of gynecomastia is unknown (idiopathic). The other common causes of gynecomastia are listed in Table 57.1. Gynecomastia often appears transiently at birth. The process is thought to be related to an increased level of circulating maternal estrogens. After birth, the estrogen level decreases, the gynecomastia resolves, and treatment is rarely necessary.

Gynecomastia is said to occur in almost two-thirds of adolescent boys.3 This is thought to be due to an imbalance of estradiol and testosterone. The adolescent gynecomastia also resolves in the vast majority of cases.2 In some cases, a degree of gynecomastia remains, but is not problematic enough to warrant medical attention. In the adolescent male, obesity is frequently associated with enlarged breasts. This may be due to the elevated levels of estrogen.4 The initial treatment is weight loss, but if this is not successful, surgical correction may be indicated.

The incidence of gynecomastia rises again in older men (age > 65 years). This is thought to be due to a decline in testosterone and a shift in the ratio of testosterone to estrogen.

In all three age groups (neonatal, adolescent, and older men), gynecomastia appears to be related to either an increase in estrogens, a decrease in androgens, or a deficit in androgen receptors.2 There are also numerous drugs and medications that cause gynecomastia (Table 57.1). Systemic causes include adrenal diseases, liver diseases, pituitary tumors, thyroid disease, and renal failure. Tumors of adrenal, pituitary, lung, and testis can be associated with hormonal imbalance resulting in gynecomastia.

In any male patient with breast enlargement, breast cancer must be considered since 1% of all breast cancers occur in men. There is no increased risk of breast cancer in patients with gynecomastia when compared with the unaffected male population.5 The exception is patients with Klinefelter syndrome. These patients have an approximately 60 times increased risk of breast cancer.

PATHOLOGY

Three types of gynecomastia have been described: florid, fibrous, and intermediate.6 The florid type is characterized by an increase in ductal tissue and vascularity. A minimal amount of fat is mixed with the ductal tissue. The fibrous type has more stromal fibrosis with few ducts. The intermediate type is a mixture of the two. The type of gynecomastia is usually related to the duration of the disorder. Florid gynecomastia is usually seen when the breast enlargement is of new onset within 4 months. The fibrous type is found in cases where gynecomastia has been present for more than 1 year. The intermediate type is thought to be a progression from florid to fibrous and is usually seen from 4 to 12 months.6,7

DIAGNOSIS

A careful history and physical examination is the most important part of any workup for gynecomastia. The history notes the time of onset of the gynecomastia, symptoms associated with the gynecomastia, drug use (both medically prescribed and recreational), and careful review of systems. Organ system changes associated with gynecomastia include liver, renal, adrenal, pulmonary, pituitary, testicular, thyroid, and/or prostate.

Physical examination includes assessment of the breast gland and includes the nature of the tissue, isolated masses, and tenderness. The thyroid is evaluated for enlargement. The testes are examined for asymmetry, masses, enlargement, or atrophy.

Laboratory evaluation is based on the findings of the history and physical examination. Healthy adults with a normal physical examination (other than gynecomastia) and longstanding gynecomastia do not require further workup.

Patients with feminizing characteristics should undergo endocrine testing. In addition, if marfanoid body habitus is associated with the feminization, Klinefelter syndrome must be ruled out. Any other new positive findings on physical examination are evaluated in an appropriate manner.

CLASSIFICATION

Simon, Hoffman, and Kahn8 divided gynecomastia into four grades: grade 1: small enlargement, no skin excess; grade 2a: moderate enlargement, no skin excess; grade 2b: moderate enlargement with extra skin; grade 3: marked enlargement with extra skin. In their opinion, grades 2b and 3 require some skin resection. The need for skin excision also depends on the shape of the breast. Large breasts with wide bases may be treated without skin excision. On the other hand, smaller, narrow breasts may require skin excision.

Letterman and Schuster9 created a classification system based on the type of correction: 1: intra-areolar incision with no excess skin; 2: intra-areolar incision with mild redundancy corrected with excision of skin through a superior periareolar scar; and 3: excision of chest skin with or without shifting the nipple.

Rohrich et al.,10 in a paper discussing the utility of ultrasound-assisted liposuction in the treatment of gynecomastia, developed the following classification: grade I: minimal hypertrophy (<250 g of breast tissue) without ptosis; grade II: moderate hypertrophy (250 to 500 g of breast tissue) without ptosis; grade III: severe hypertrophy (>500 g breast tissue) with grade I ptosis; grade IV: severe hypertrophy with grade II or III ptosis.

TREATMENT OF GYNECOMASTIA

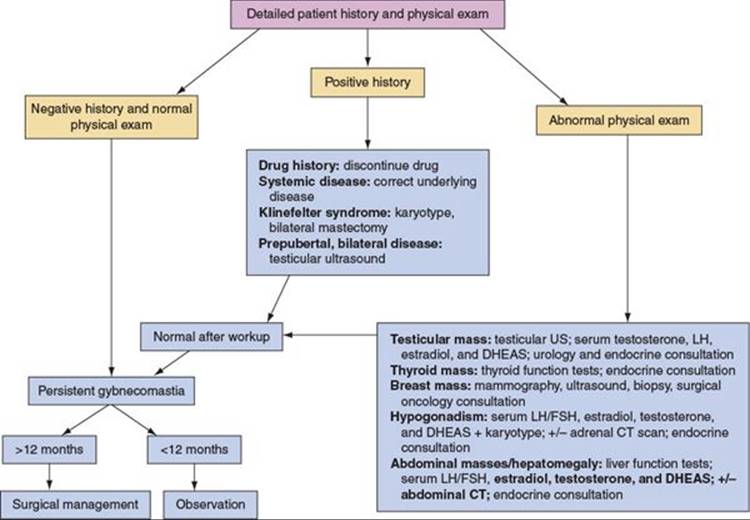

In patients with gynecomastia for more than 1 year and with a normal history and physical examination, surgery may be indicated. If there is a possible etiology noted in the patient’s history, then an attempt should be made to either discontinue the drug believed to be causing the gynecomastia or correct the systemic condition. If an abnormality is found on physical examination, workup is indicated prior to surgical intervention for the gynecomastia. If the underlying condition is treated and the gynecomastia persists beyond a year, surgical correction is indicated (Figure 57.1).

The first surgical procedures used to treat gynecomastia were excisional in nature.11 Suction-assisted lipectomy was first reported in the early 1980s,12 and more recently ultrasound-assisted liposuction has been used for certain types of gynecomastia.10 The physical deformity determines the appropriate surgical technique for the treatment of gynecomastia.

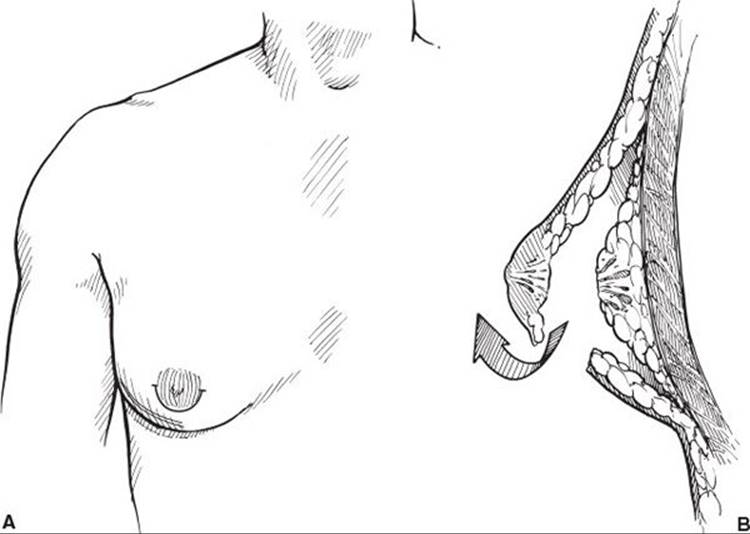

Most fibrous or solid Simon stage 1 or 2a lesions are treated with surgical excision or more recently, in selected cases, with ultrasonic liposuction. If surgical excision is chosen, a periareolar incision is performed as indicated in Figure 57.2A. The skin incision is placed at the junction of the areola and skin. If placed within the pigmented area, the scar may appear as a white line. If placed outside the areola, it may become hypertrophic. The site of the incision should be marked prior to the distortion caused by injection of epinephrine-containing solution. If placed properly, the ultimate scar is usually nearly invisible. After the incision is made, a cuff of tissue 1 to 1.5 cm in thickness is preserved directly deep to the nipple/areola complex. This maneuver prevents postoperative nipple/areola depression or adherence of the nipple/areola to the chest wall (Figure 57.2B). It is always better to leave more tissue under the nipple–areola than less. At the end of the case any excess is trimmed. The chest skin flaps are developed in a plane between the subcutaneous fat and the breast tissue. To assure a smooth contour, the edges of the breast are trimmed with either scissors or liposuction.

FIGURE 57.1. Algorithm for evaluation and treatment of gynecomastia. US, ultrasound; LH, luteinizing hormone; DHEAS, dihydroepiandrosterone sulfate; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; CT, computed tomography. Adapted from Rohrich RJ, Ha RY, Kenkel JM, Adams WP. Classification and management of gynecomastia: defining the role of ultrasound-assisted liposuction. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:909.

FIGURE 57.2. A. Periareolar incision. Medial and lateral extensions only used if necessary. B. Resection of gynecomastia through periareolar incision. Note the cuff of tissue left deep to the areola.

Patients with lesions that are glandular, fatty, or mixed in nature and that are Simon grade 1 or 2a may be treated with liposuction. Conventional liposuction with sharp tip cannulas, power-assisted liposuction, or ultrasound-assisted liposuction has been used successfully in this situation.

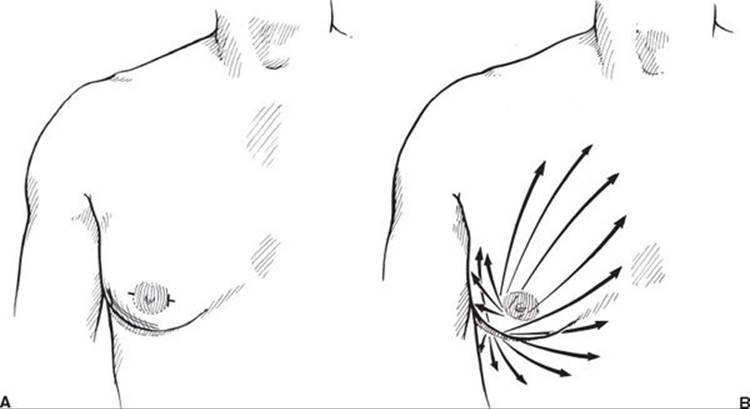

The patient is marked in the upright position. All areas of tissue excess are marked as well as the inframammary fold. Sedation or general anesthesia is necessary. The area is infiltrated with a tumescent solution that contains lactated ringers solution, 1 cc of 1:1,000 epinephrine solution, and 20 cc of 2% lidocaine. The infiltration volume is about 1:1 with the expected aspiration volume and covers a wide area of the chest from the clavicle to below the inframammary fold. Regardless of the type of liposuction chosen, special cannulas specifically designed for gynecomastia surgery are used. The typical incisions are shown in Figure 57.3A; typically, a lateral incision at the level of the inframammary fold and a periareolar incision are made. Liposuction is performed in all directions through both incisions (Figure 57.3B). The inframammary fold is disrupted. The end point is a flat, smooth contour with an absence of palpable tissue (Figure 57.4). In cases of pure fatty gynecomastia, no further surgery is necessary.

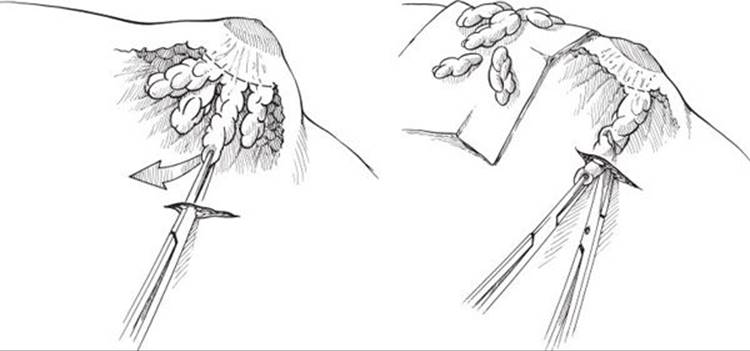

When liposuction is unsuccessful at removing all of the tissue required to achieve a good result, the pull-through13,14 technique is added. In this technique, either the lateral or periareolar incision is opened slightly (about 1.5 cm) and the residual tissue is grasped. The tissue is pulled out through the wound and removed with scissors or electrocautery. The pull-through resection is performed until the desired contour is achieved. Again, over-resection of the subareolar area is assiduously avoided (Figure 57.5). Drains are placed if the dead space is large. All patients are treated with compression garments for at least 1 month.

In patients with Simon grade 2b gynecomastia, the initial treatment is similar to that in patients with grade 1 and 2a gynecomastia. If the lesion is fatty, glandular, or mixed in nature and some type of liposuction is the initial treatment modality, then no skin resection is performed at the first surgical session. The patient is treated with a compression vest and the chest wall tissue is given time to settle and contract. The patient should wait at least 6 to 12 months before considering skin resection. In the majority of cases, no skin resection is required. When skin resection is performed, the amount of skin removed and the length of the incisions are less than if the resection had been performed at the time of the initial surgery.

FIGURE 57.3. A. Location of incisions for suction-assisted lipectomy of gynecomastia. B. Direction of liposuction through both incisions.

FIGURE 57.4. Patient with Simon 2a gynecomastia who underwent suction-assisted lipectomy of the chest (A–D). A, B. Pre-op appearance. C, D. Post-op appearance.

If the patient has a Simon grade 2b lesion that is very solid or fibrous in nature and an open approach is selected, then skin resection may be incorporated into the initial procedure. Alternatively, the tissue is resected via a minimalistic periareolar incision and the patient treated with a compression garment. In many cases, no further skin resection is required. Ultrasonic liposuction with the pull-through technique (if needed) has also been used in Simon 2b cases without skin resection with good results.

FIGURE 57.5. Pull-through resection of gynecomastia demonstrated.

In patients with Simon grade 3 gynecomastia, skin resection is required. Numerous incisions and techniques have been described to resect the skin and maintain nipple/areola viability, including superior and inferior periareolar incisions, omega incisions, nipple transpositions on a variety of pedicles, concentric circle techniques, and any form of liposuction with skin excision. The choice of technique is based on the preference of the surgeon.

COMPLICATIONS

The most common early complication after gynecomastia surgery is hematoma. In an open case, the hematoma should be evacuated if possible. This prevents excessive scarring and distortion of the breast. Postoperative closed suction drainage decreases the incidence of this complication. In liposuction cases, evacuation may not be possible.

Under-resection of tissue is the most common long-term complication of gynecomastia surgery. This is particularly common in liposuction cases, when a residual mass of tissue is not removed. This can usually be avoided using the pull-through technique. Under-resection at the periphery of the breast can result from poor tapering and causes a noticeable deformity. Over-resection in the nipple–areola can result in a saucer-type deformity that is difficult to correct. Loose skin is usually not considered a complication if it is part of the operative plan. Occasionally, loose skin occurs unexpectedly, and surgical excision is required.

Postoperative wound infection is uncommon. The use of prophylactic antibiotics, particularly in liposuction cases, may account for the low incidence of this complication.

References

1. Goldwyn R. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Breast. Boston, MA: Little Brown; 1976;93:305.

2. McGrath MH. Gynecomastia. In: Jurkiewicz MJ, Mathes SJ, Krizek TJ, Ariyan S, eds. Plastic Surgery: Principles and Practice. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1990;1119.

3. Nydick M, Bustos J, Dale JH, Rawson RW. Gynecomastia in adolescent boys. JAMA. 1961;178:449.

4. Hammond D. Surgical correction of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:61e.

5. Cohen IK, Pozez AL, McKeown JE. Gynecomastia. In: Courtiss EH, ed. Male Aesthetic Surgery. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1991;373.

6. Bannayan GA, Hajdu SI. Gynecomastia: clinicopathologic study of 351 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1972;57:431.

7. Hands LJ, Greenall MJ. Gynecomastia. Br J Surg. 1991;78:907.

8. Simon BE, Hoffman S, Kahn S. Classification and surgical correction of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;51:48.

9. Letterman G, Schuster M. The surgical correction of gynecomastia. Am Surg. 1969;35:322.

10. Rohrich RJ, Ha RY, Kenkel JM, Adams WP. Classification and management of gynecomastia: defining the role of ultrasound-assisted liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:909.

11. Webster JP. Mastectomy for gynecomastia through a semi-circular incision. Ann Surg. 1946;124:557.

12. Courtiss EH. Gynecomastia: analysis of 159 patients and current recommendations for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:740.

13. Hammond DC, Arnold JF, Simon AM, Cararo A. Combined use of ultrasonic liposuction with the pull-through technique for the treatment of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:892.

14. Bracaglia R, Fortunato R, Gentileschi S, Seccia A, Farallo E. Our experience with the so-called pull-through technique combined with liposuction for management of gynecomastia. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;53:22.