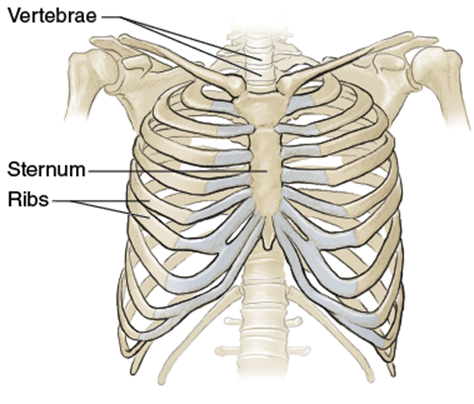

Anyone who understands the function of a bellows or an accordion will soon grasp the anatomy of the thorax, commonly known as the chest. Bellows and accordions have evolved over many years as a way to move air under pressure and produce an air current or musical sounds. The principal bony architecture of the chest (figure 5.1) consists of 12 thoracic vertebrae, each placed one on top of another, but interlocked by ligaments and other soft tissues in such a manner that there can be movement in anterior (front) and posterior (rear) directions, limited lateral (side) motion, and a degree of rotation that allows the torso to twist. Emerging from the side of every thoracic vertebra are two bony ribs that encircle the body and meet at the front, the majority of them forming the sternum, or breastbone.

Figure 5.1 Bony structures of the torso: ribs, sternum, and vertebrae.

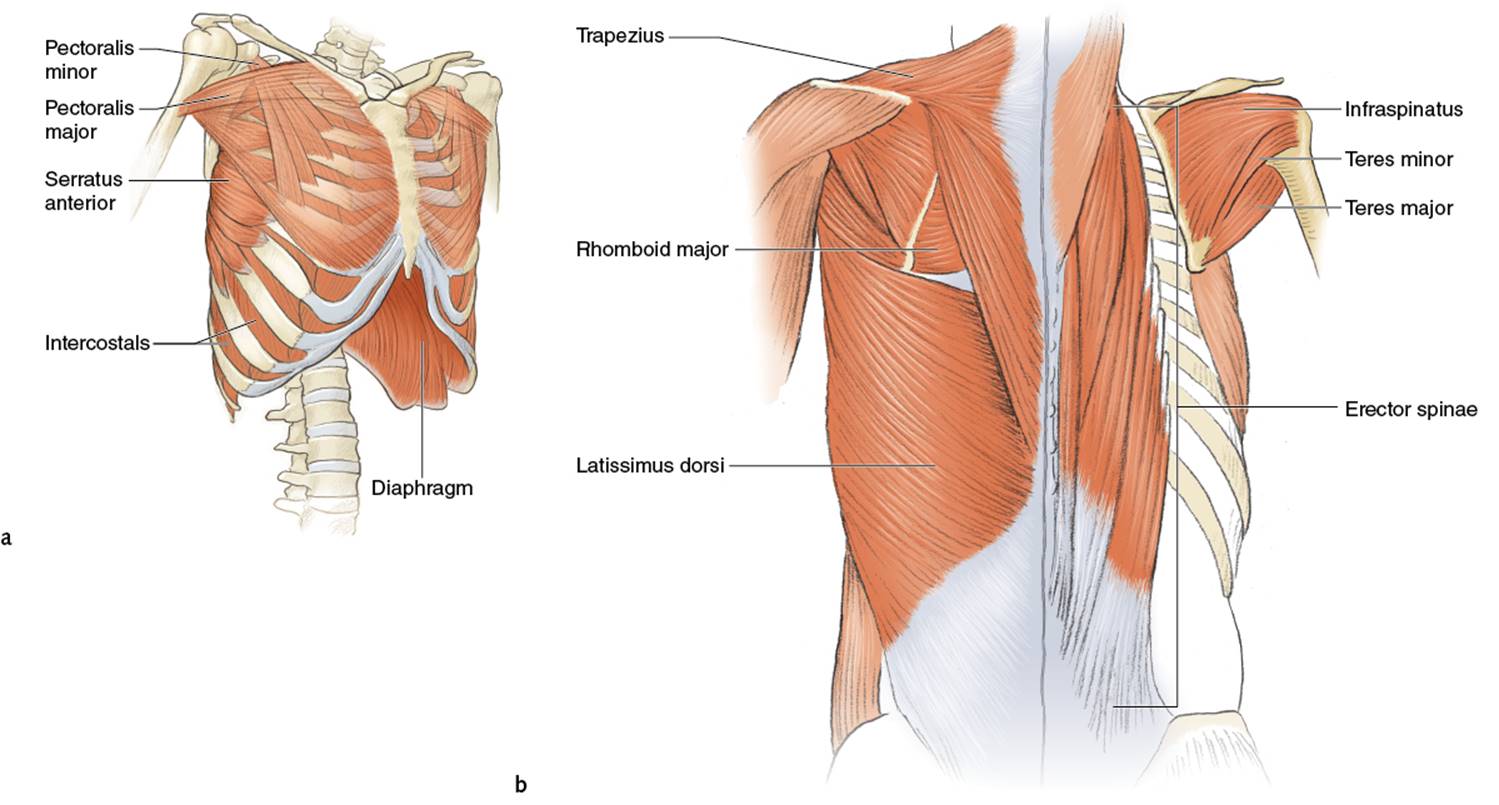

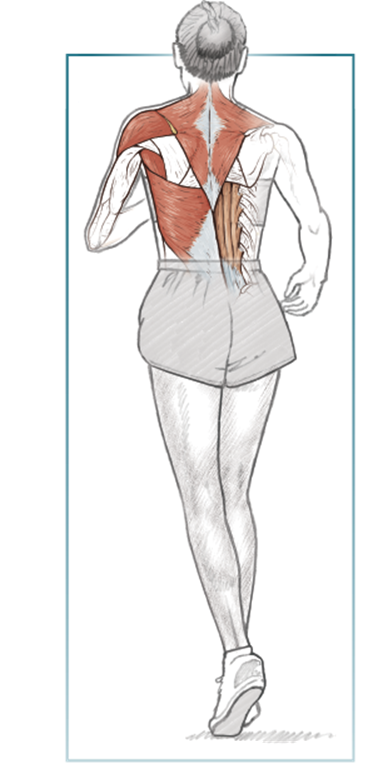

Although the outside or posterior of the vertebrae are supported by the erector spinae muscles, which run the length of the spine, each rib hangs from the one above, held together by the intercostal muscles, much in the fashion of a venetian blind. Without further structural support, these would be unstable, so the trapezius, latissimus dorsi, rhomboid, teres group, shoulder stabilizers, and pectoralis major and minor (figure 5.2) all aid in the maintenance of the relative position of the ribs. At the base of this dome, with attachments to the lower ribs, lies the vast diaphragm, encircling the base of the thorax. Further stability is given by the abdominal muscles, rectus abdominis, the external oblique, and serratus anterior.

Figure 5.2 Upper torso: (a) front view and (b) back view.

Running makes far greater demands on the body for oxygen than does sedentary life. The diaphragm uses a bellowslike action as it contracts to draw air into the lungs. At the same time, the intercostal muscles relax, only to contract strongly as expiration occurs, during which time the diaphragm relaxes and is drawn up into the thorax. Using this push–pull endeavor, the lungs fill with air and empty to maintain the oxygen needs of the runner.

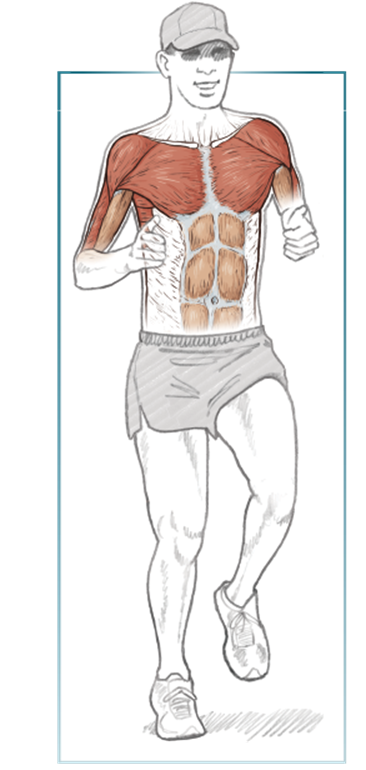

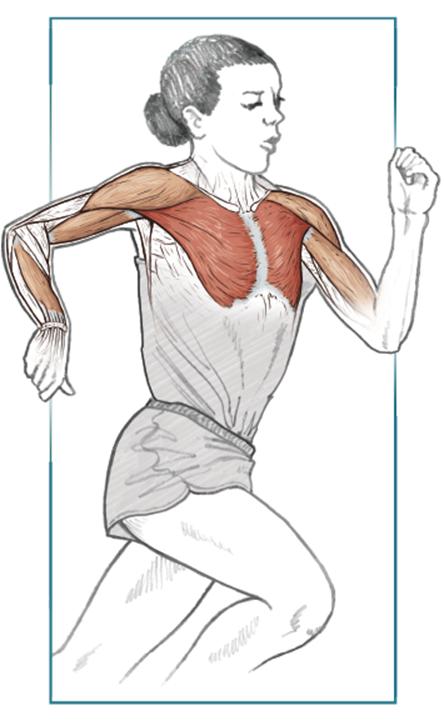

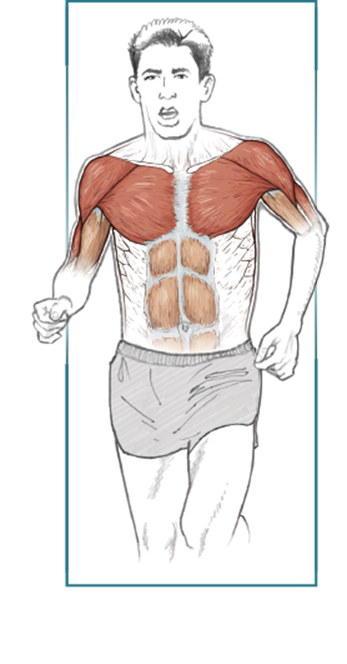

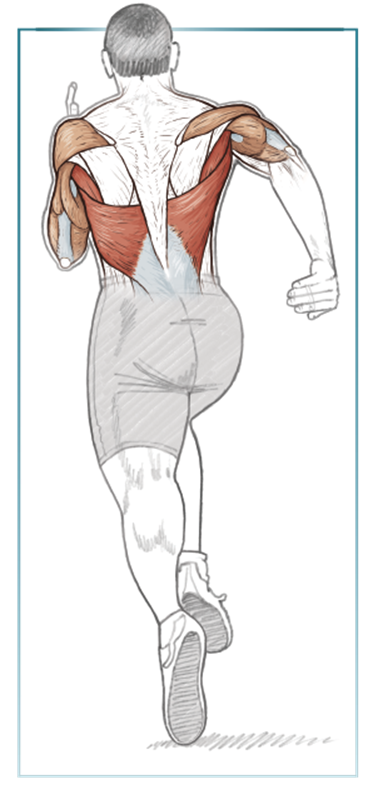

As well as their action in the mechanisms of breathing, the muscles of the thorax have a limited but significant part to play in forward motion. The best way to appreciate this is to view an approaching runner in slow motion. As the thigh moves forward with each stride, the pelvis rotates slightly, first one side, and then the other. This twists the spine a little and would cause instability within the abdomen and thorax if unchecked, so a small but significant tensing and relaxation of the thoracic musculature helps not only to maintain the vertical component, but also to correct variations that are caused by forward motion of anything up to 20 miles per hour (32 k/hr).

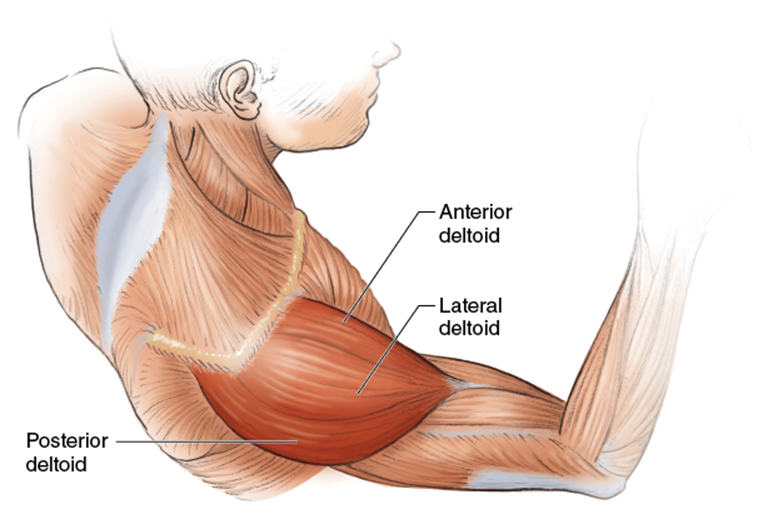

The muscles that are attached to the shoulders and humerus, particularly the pectorals and teres, are also moved passively when the arms swing fore and aft with each stride. If they contract actively, they too will help move the upper arms to a small extent as they oppose the pull of the deltoid (figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3 The deltoid.

The importance of these muscles in running lies with the “weakest link” presumption—that the power of the runner is dependent not on the strength that he can produce but on which facet of his running body tires first. If the muscles of the thorax are undertrained and fatigued, they will be unable to perform their functions and so reduce the efficiency of the running action and the runner himself. If the thoracic muscles lose strength and power, not only is the breathing action compromised, but also the auxiliary actions to support the spine and aid the arm movement will be weakened, leading to an inevitable slowing.

Having watched runners for many years, it is surprising how many feel that they can only improve if they increase the pace or quantity of their training. Many do not realize that the limits to their running will always be related to the weakest part of their body. The legs may be capable of a mile in under four minutes, but if the lungs do not have the capacity to provide oxygen to those legs, then they are only going to be able to achieve the speed allowed by the lungs, and not that of which the legs may be capable of under other circumstances. To avoid this disparity, the diaphragm and all the supporting muscles need to be just as fit as those of the lower limbs. These muscles become fatigued by exercise in exactly the same way as do all other muscles, so it seems logical that they need to be as highly trained as any other group of muscles involved in exercise. It is for that reason that the training exercises included here should be considered as important as all those that are prescribed for the legs.

Choosing Resistance

Initially, choose weights for each exercise that provide a moderate amount of resistance but that allow for the strength-training movement to be performed by maintaining proper technique for the entire set of repetitions. The weight should be increased as strength improves and adaption becomes apparent through easier performance of the exercise; however, the weight should never be so heavy that proper technique is compromised, even on the final few repetitions of a set. Factors such as which part of the anatomy is being strengthened also factor into the decision on weight used.

For example, the pectoral muscle is large, and therefore can handle a large amount of work. The triceps, comprised of three much smaller muscles, fatigues quite quickly when it is the primary muscle group used; however, because the triceps is involved secondarily in many upper-body exercises, it will already be slightly fatigued before any triceps-specific exercises are performed. One triceps-specific exercise per strength-training session that involves the arms should suffice to strengthen the triceps sufficiently. Conversely, multiple chest exercises or many sets of the same exercise will be needed to sufficiently fatigue the larger pectoral muscle.

Repetitions

The amount of repetitions should vary based on the strength-training goal of the exercise and the objectives of the entire strength-training workout for that day. For example, two sets of 20 dumbbell presses and a set of 30 push-ups may function as an entire chest workout on a Monday, but on Friday, one set of 12 repetitions with a heavier weight than lifted Monday, followed by two sets of 10 repetitions of incline barbell presses and three sets of 15 push-ups may be what is called for. A general rule to follow is that the heavier the weight, the fewer reps performed, and vice versa.

Breathing

Exhale when forcibly moving the weight and inhale when performing the negative movement or resisting the weight. When generating movement, exhale; when resisting movement, inhale. The speed of each exercise should be as fluid and controlled as possible and should be in relationship to the breathing pattern. An accepted breathing pattern is four seconds for the resistance (inhalation phase) and two seconds for the movement (exhalation phase).

Schedule

A varied resistance-training routine works best. The concept of work plus rest equals adaption has a caveat. The work must change over time both in quantity of work (amount of resistance) and in quality of work (type of exercise) to ensure continued strength gains. For each segment of the body examined in this book, we have provided multiple exercises, some with variations, that can be used to create a multitude of different strength-training sessions all geared toward strengthening the anatomy that is most involved in running. By changing exercises, the number of sets and repetitions, and the exercise order, runners can tailor their strength-training sessions to meet their fitness needs and time constraints. No workout need be longer than 30 minutes, and two to three sessions per week can dramatically enhance a runner’s performance by strengthening the specific anatomy used during run training and racing. We are not suggesting that just lifting weights will make you a better runner. We are suggesting that through proper strength training, your anatomy will be strengthened, and this resultant strength will aid running performance by eliminating muscle imbalances that impede the gait cycle, help in respiration, and help eliminate injuries that result from muscle imbalances.

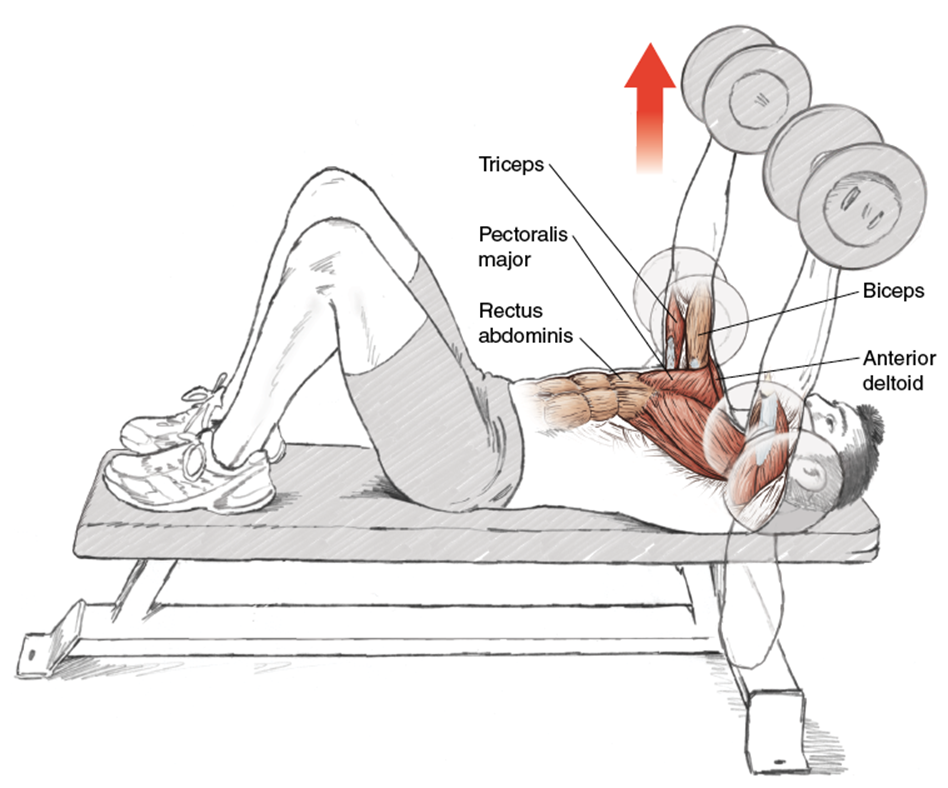

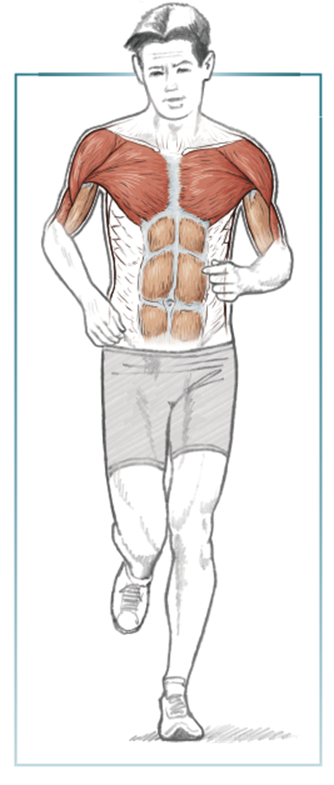

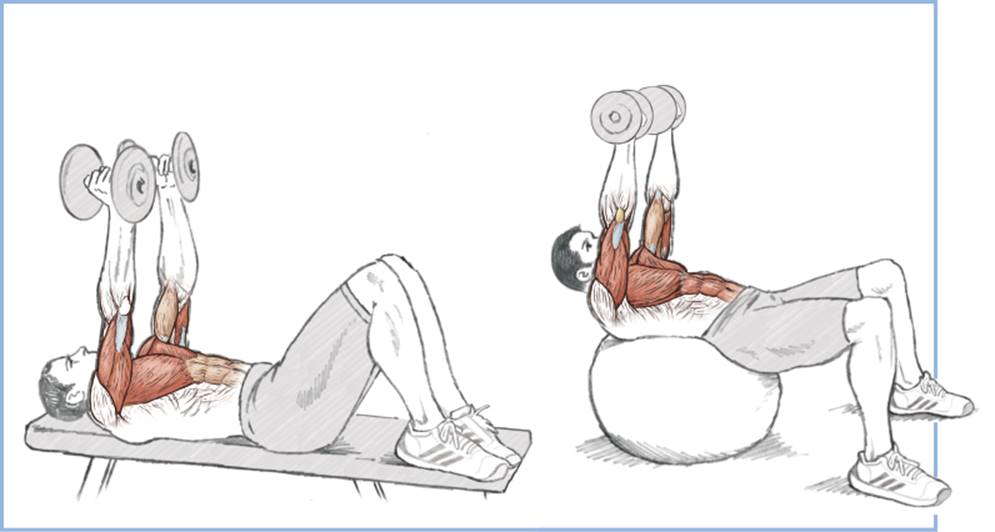

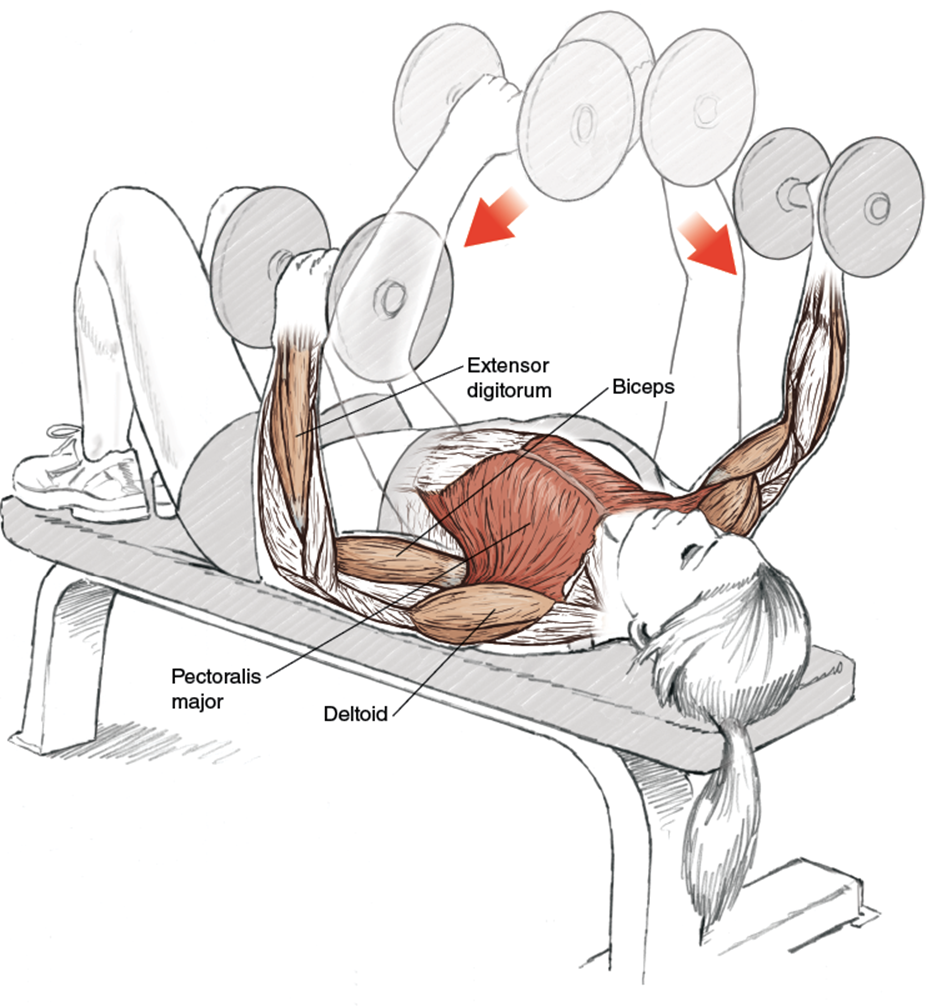

Dumbbell Press

![]()

Safety Tip

For the physioball dumbbell press variation, the weight of the dumbbells should be reduced because of the relative instability of the physioball versus the bench, but after becoming comfortable with the movements, dumbbell weight can be added.

Execution

1. Lie supine (back down) on a bench with legs steepled and feet on the bench. There should be a small, natural bend in the lower back so it does not touch the bench. A dumbbell should be held in each hand, at chest level.

2. Press the dumbbells upward to full extension. When full extension is reached, immediately lower the dumbbells slowly to the original position.

3. Repeat the movement, keeping in mind the stable position of the back against the bench.

Muscles Involved

Primary: pectoralis major, triceps, anterior deltoid

Secondary: biceps, rectus abdominis

Running Focus

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, the muscles of the chest become fatigued by exercise in exactly the same way as do all other muscles, so developing these muscles through a simple exercise like the dumbbell press is both easy and beneficial. This exercise recruits the abdominal group more than the barbell bench press because the torso requires stabilization as a result of the independence of each dumbbell. It targets the pectoral muscle group and uses the abdominal group as stabilizers. The stronger the abdominal and pectoral group are, the better the posture of a distance runner in the latter stages of a race or training run, as well as the cardiovascular benefit of improved respiration. The better the upper-body posture of a runner, the more efficient the gait cycle is, aiding the runner by not wasting precious energy on poor running mechanics.

Variations

Rotated Dumbbell Press

This variation develops the sternal head of the pectoral group. It helps fully develop the pectoral group.

Dumbbell Press on Physioball

The use of the physioball enhances the role of the abdominal group as stabilizers for the exercise.

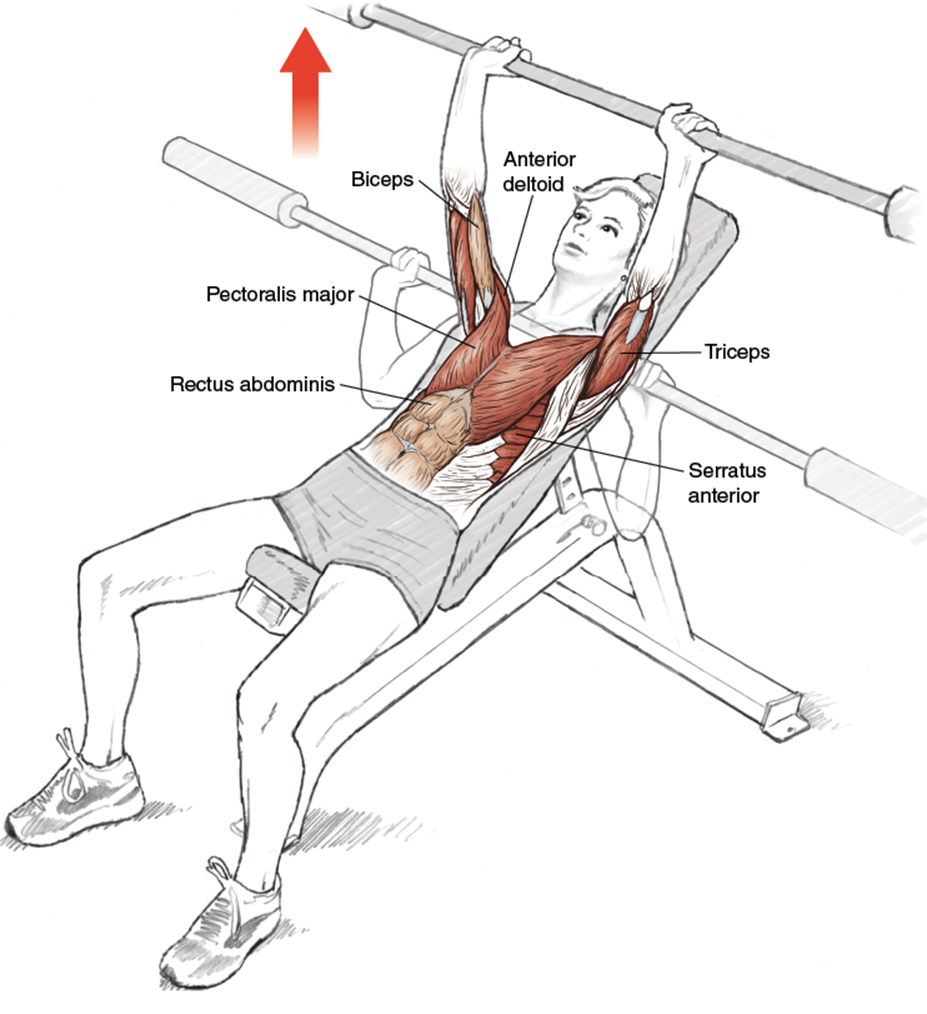

Incline Barbell Press

![]()

Safety Tip

Use of a spotter is highly recommended to help with removing and placing the barbell back on the stays of the bench. Because of the inclined nature of this exercise, there is more shoulder involvement—specifically, the rotator cuff. If any pain is felt in the shoulder, discontinue the exercise and perform only the flat dumbbell press.

Execution

1. Lie on a 45-degree incline bench. With arms extended almost to their full extension, grip the barbell a little wider than shoulder width.

2. Fully extend the arms, removing the barbell from the rack. Lower the barbell in a straight line to the upper chest.

3. Press the barbell up, in a straight line, back to the original position without locking the elbows.

Muscles Involved

Primary: pectoralis major, triceps, anterior deltoid, serratus anterior

Secondary: biceps, rectus abdominis

Running Focus

Similar to the dumbbell press in the muscles engaged, the incline press also involves the serratus anterior, adding to the development of the upper body. By adding variation to a strength-training routine through the use of different exercises that stimulate muscle growth in the same area, a runner can avoid becoming bored with a regimen. Because the strength-training component is meant to complement and enhance run training, performing new exercises helps keep the training fresh.

Dumbbell Fly

![]()

Safety Tip

Note that you begin the exercise with the dumbbells extended, not outstretched. Lifting the dumbbells to begin the exercise can be difficult if heavy weight is used, and starting in the outstretched position places the deltoids and biceps in an awkward position. Also, do not lower the arms past the plane of the bench top for fear of injury.

Technique Tip

•When returning the weight to the overhead position, do not push the weight with your hands or overly engage your deltoids. Your pectorals should do the lifting.

Execution

1. Begin by lying supine on a bench with legs steepled and feet on the bench. There should be a small, natural bend in the lower back so it does not touch the bench. Arms are extended perpendicular to the body with 5 to 10 degrees flex in the elbows. Hands grip the dumbbells, palms facing inward.

2. Lower the weight slowly, focusing on the stretch of the pectoral muscles while maintaining bent elbows, until the upper arms are outstretched and in the same plane as the bench top.

3. Return the weight to the starting position as if you were hugging a barrel. Control the dumbbells so they do not touch at the top, but are separated by 2 or 3 inches.

Muscles Involved

Primary: pectoralis major

Secondary: biceps, deltoid, extensor digitorum

Running Focus

The emphasis on strengthening the pectoral muscles has been noted in all the exercises listed in this chapter. However, the benefits of the dumbbell fly include the stretching of the pectoral muscles, specifically during the negative, or lowering, phase of the exercise. This stretching helps expand intercostal muscles between the ribs, allowing for better respiration. Essentially, the more the muscles of the chest are expanded, the easier it is to inhale oxygen. This is reflected in the large rib cages of elite marathoners like Ethiopian Haile Gebrselassie and American Ryan Hall. Their chests always seem expanded when they run, most likely to accommodate their exercise-enlarged lungs.

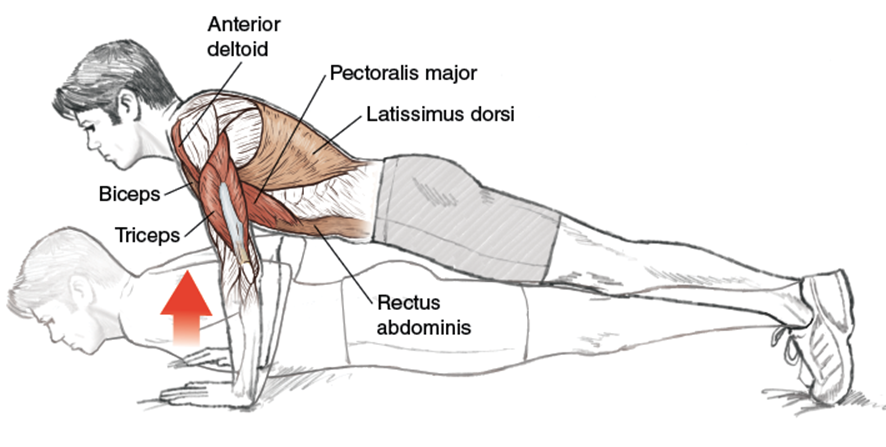

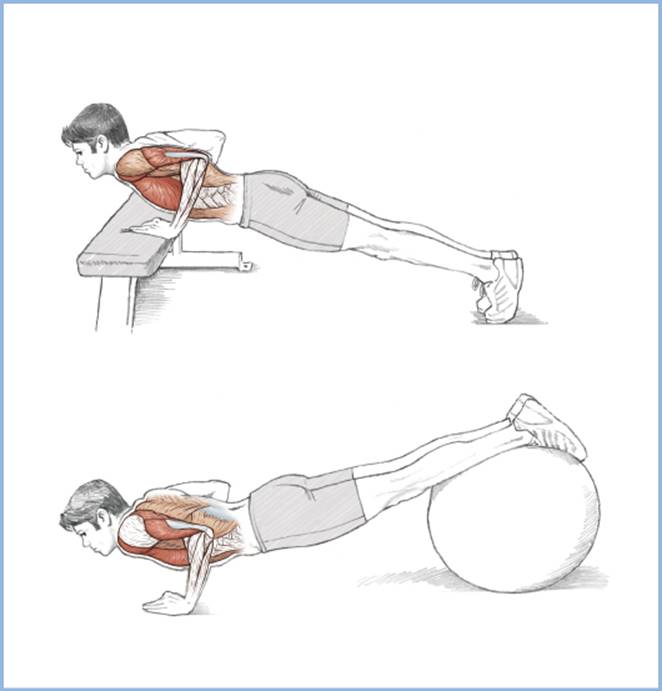

Push-Up

Execution

1. Start in a prone position, arms bent, slightly wider than shoulder-width apart, but in a straight line with the outsides of the shoulders.

2. Push away from the floor in a single, controlled movement, keeping your body in one slight upward plane (from feet to head) until your arms are fully extended. Exhale while performing the push-up.

3. Lower your body slowly by bending at the elbows until the chest is parallel and touching or near touching the floor. Inhale during this phase of the exercise.

Muscles Involved

Primary: pectoralis major, triceps, anterior deltoid

Secondary: biceps, latissimus dorsi, rectus abdominis

Running Focus

The push-up is the purest strength exercise. No machines. No weights (other than your own body weight). One fluid movement. It is not complicated unless you add variations (incline push-up and push-up on physioball), but it is a highly effective exercise for developing upper-body strength.

Push-ups benefit a runner by strengthening the upper body and abdominals, ensuring proper posture. The technique involved in completing a push-up is similar to the position of the upper body during running, so the exercise reinforces correct posture.

Multiple sets of push-ups can be done, but like any strength-training activity, push-ups should not be done daily, but following a rest period that allows for the mending of the muscle fibers used during the push-up session.

Variations

Incline Push-Up

Incline push-ups shift the emphasis of the exercise to the upper chest and the muscles of the shoulders. A greater number of push-ups can be performed, so incline push-ups are a good exercise to begin with if regular push-ups are difficult. Because the exercise is easier, you may be tempted to accelerate the motion, but resist this temptation. The rotator cuff is more involved in incline push-ups, and accelerating the motion could lead to a shoulder injury.

Push-Up on Physioball

Decline push-ups shift some of the emphasis to the upper back. Using a physioball while performing this exercise requires core stabilization, so this exercise aggressively targets secondary muscle groups. Try to keep your hips from sinking toward the ground during the execution of the push-up. Maintain a rigid posture. If this is difficult, use a smaller physioball, which makes the exercise easier.

![]()

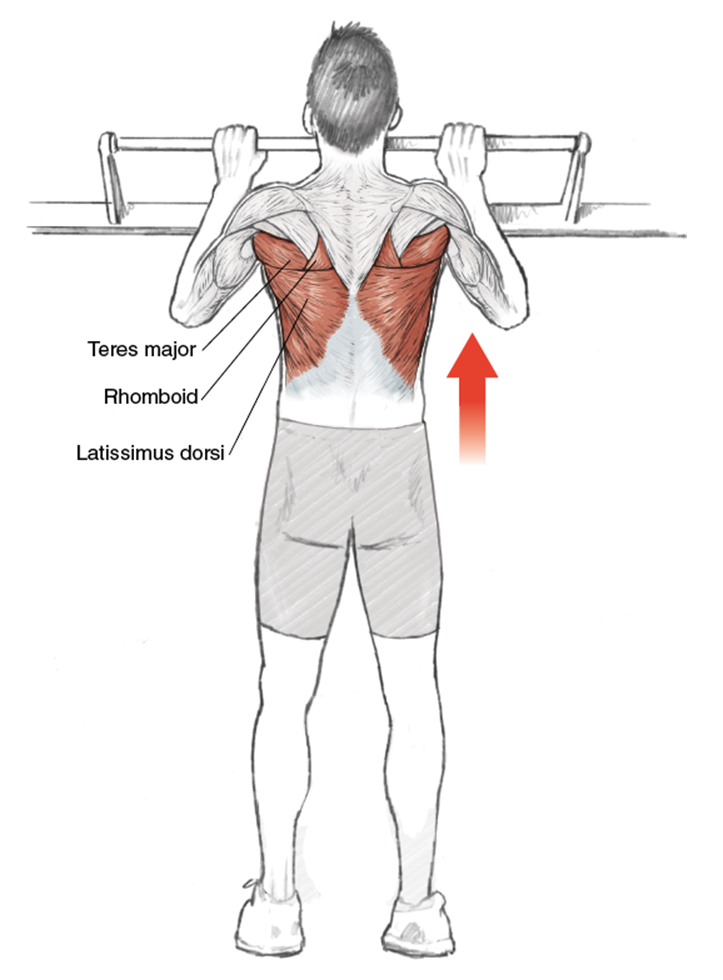

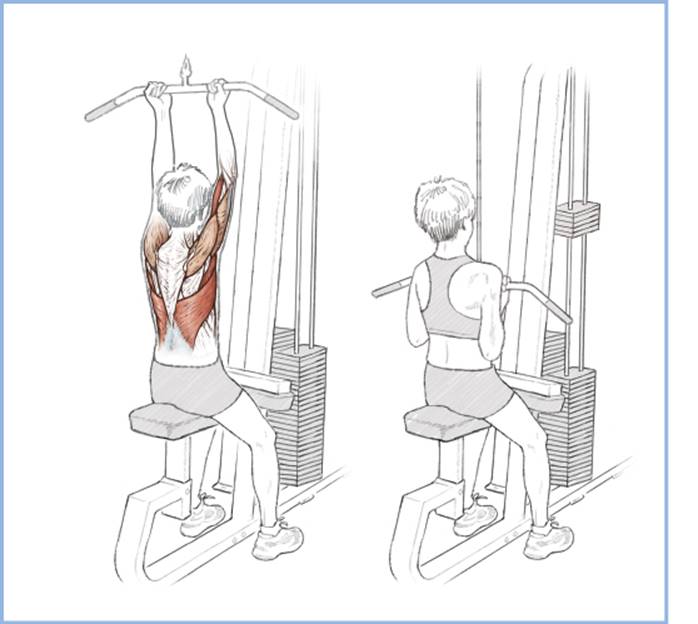

Pull-Up

Execution

1. Use an overhand (palms forward) grip and hang from the pull-up bar, getting a full stretch.

2. Pull your body weight upward using a fluid motion.

3. When the chin reaches bar height, lower your body in a controlled movement back to almost full extension of the arms. Feet should not touch the floor during repetitions.

Muscles Involved

Primary: latissimus dorsi, teres major, rhomboid

Secondary: biceps, pectoralis major

Running Focus

The pull-up is the yin to the push-up’s yang. It is simply performed, but powerful in providing strength benefits. It helps strengthen the upper back, and as distance runners can attest, a strong upper back makes for better running posture during the later stages of a training run or long race.

The U.S. Marine Corps and other branches of the military use the pull-up (and push-up) to measure the fitness of their soldiers. A perfect score is 20 pull-ups in one minute.

Pull-ups are a difficult exercise. To aid in starting the exercise, stand on a box to begin the first rep. Do only the amount of pull-ups that can be done with a fluid, controlled movement. Do not wriggle or bounce.

Often pull-ups are called chin-ups. Some trainers distinguish between pull-ups and chin-ups based on the grip (palms outward or inward), but for others the difference is simply semantic.

Variation

Reverse-Grip Pull-Up

Use an underhand (palms facing toward you), shoulder-width grip. Hang from the pull-up bar, getting a full stretch. Pull your body weight upward using a fluid motion. When the chin reaches bar height, lower your body in a controlled movement back to almost full extension of the arms. Feet should not touch the floor during repetitions.

The reverse-grip pull-up involves the biceps more than the overhand-grip pull-up. Given the relatively small size of the biceps, performing this exercise is more difficult than with the overhand grip because the biceps can fatigue quickly.

The two pull-up exercises can be alternated during a strenuous upper back workout, or they can be done on different days as part of a general workout.

![]()

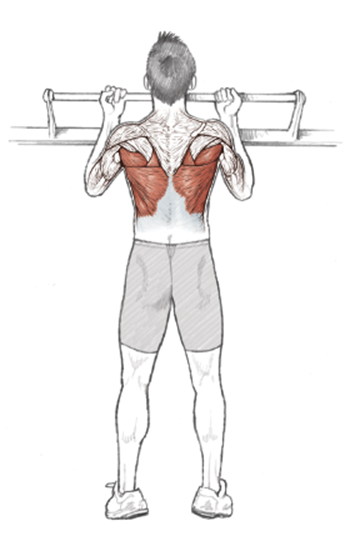

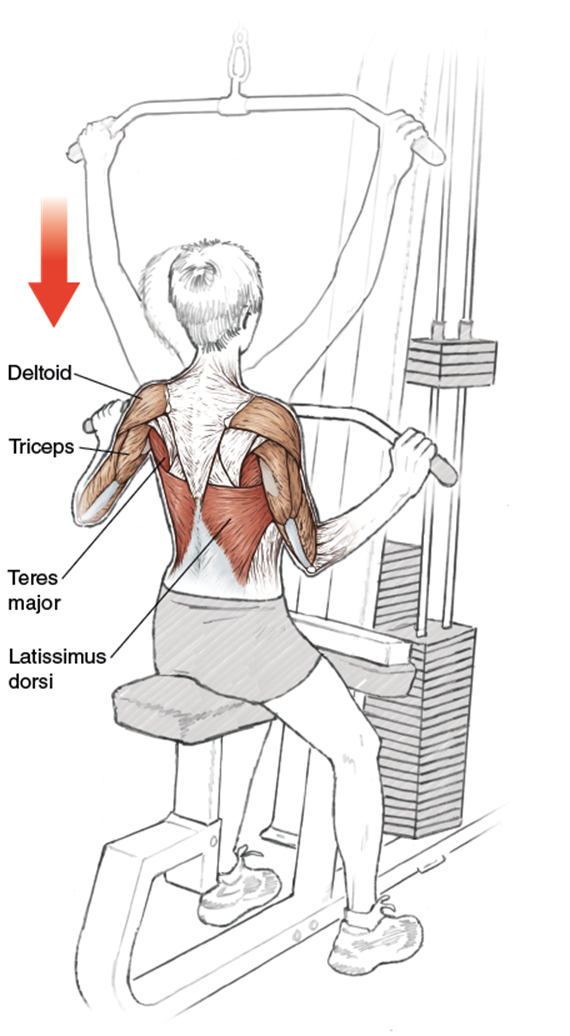

Machine Lat Pull-Down

Execution

1. Using a weight machine, face the bar with your legs under the pads and grip the bar using a wide grip. Arms are fully extended. Palms face away from the body. Your upper body is slightly rotated (shoulders back) to accommodate the exercise motion.

2. In one continuous motion, pull the bar down, with elbows back and chest out until the bar reaches the upper chest.

3. Gradually allow the arms to return to full extension while resisting the weight during the negative phase of the exercise.

Muscles Involved

Primary: latissimus dorsi, teres major

Secondary: triceps, deltoid

Technique Tip

• The lat pull-down will cause significant muscle mass to develop in the upper back if heavy weight is used as resistance. It is recommended to perform the exercise with lighter weight than the maximum and to complete multiple sets of higher repetitions.

Running Focus

The lat pull-down motion is not a normal running movement, so how does this exercise aid running performance? Like the chest and upper back exercises previously illustrated, the lat pull-down helps performance by strengthening muscles (latissimus dorsi and teres major) that support and stabilize the body’s thorax and aid in respiration and posture. The strengthening of the upper back helps counterbalance strength gained from performing the exercises targeting the chest, creating a torso that is balanced, and helps with maintaining an erect posture throughout a lengthy training or racing session. This is a good exercise to perform during the introductory phase of training.

Variation

Reverse-Grip Lat Pull-Down

This exercise emphasizes the role of the biceps as well as the latissimus dorsi and teres major. We recommend completing this exercise on a day when strengthening the arms is the focus of the workout. If you perform the lat pull-down first, you may need to change the weight load to perform the reverse-grip variation since the latter minimizes the role of the larger shoulder and upper back muscles.

![]()

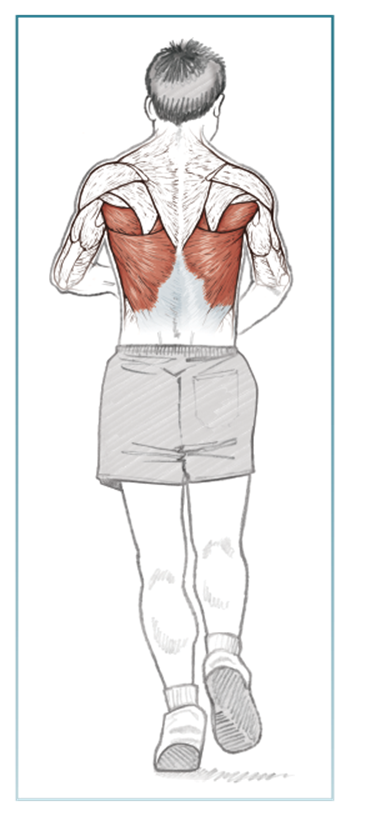

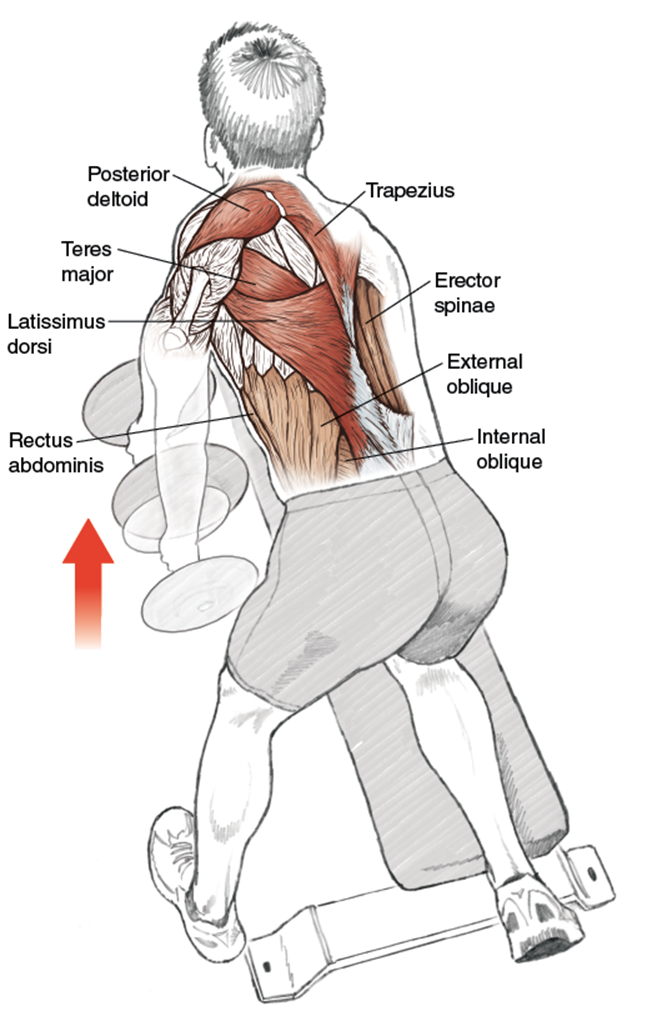

One-Arm Dumbbell Row

Technique Tip

• The movement of the exercise has been likened to that of sawing wood with a hand saw.

Execution

1. Kneel with one leg on a flat bench. Use the same-side hand (non-weight-holding hand) for support by placing it on the bench. The weight-holding hand is dropped below the bench top, arm extended down.

2. Grip the weight and, in a smooth, continuous motion initiated by the muscles of the upper back and shoulder, pull the dumbbell upward until the elbow is bent at a 90-degree angle. Exhale while performing the row.

3. Gradually lower the weight along the same path that the dumbbell traveled upward.

Muscles Involved

Primary: latissimus dorsi, teres major, posterior deltoid, biceps, trapezius

Secondary: erector spinae, rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique

Running Focus

This is an easy exercise to perform, and it benefits multiple muscles. Specifically, because a relatively heavy weight can be used (once good form is established), a lot of strength gains can occur. The development of the deltoid and trapezius will help with head position and arm carriage. Specifically, strength in these muscle groups will aid in developing a powerful arm carriage during track sessions, help fend off fatigue during longer workouts and races, and help maintain good running form during trail runs on difficult (rocky or hilly) terrain.

An important element of this exercise is the isolation of the upper back and shoulder muscles used. Although the abdominal group engages to stabilize the body, emphasis should be placed on the role of the latissimus dorsi, trapezius, deltoid, and biceps.

![]()

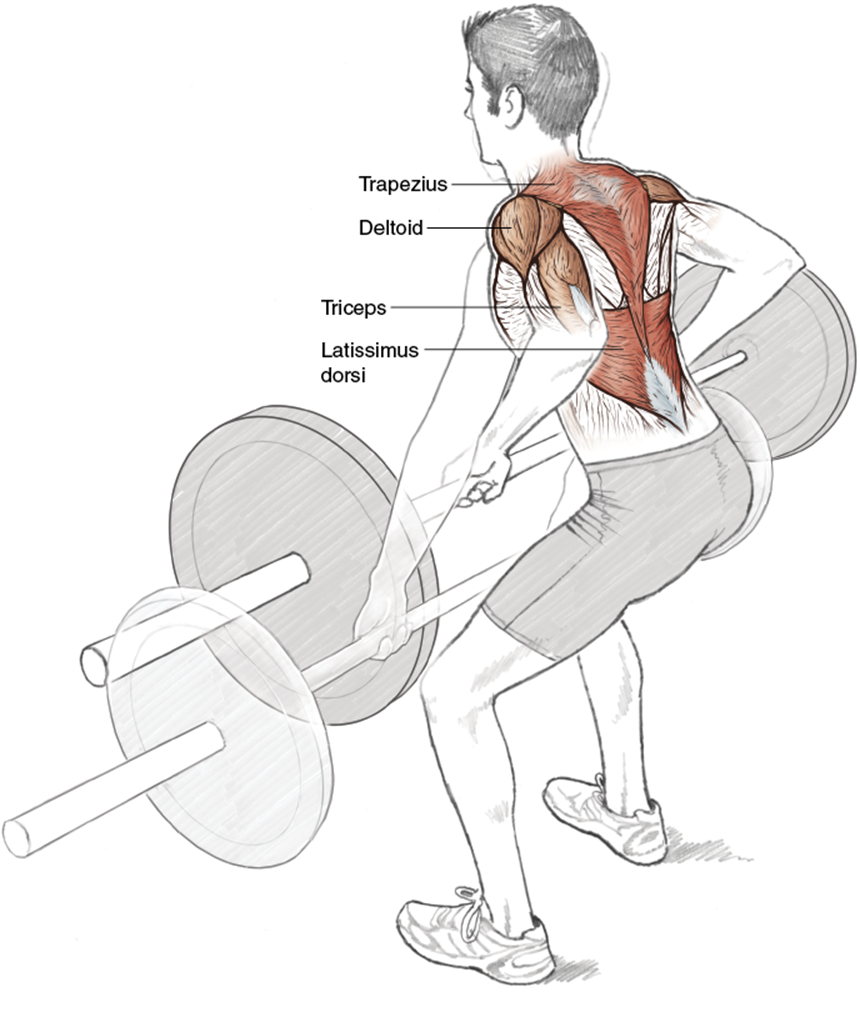

Bent-Over Row With Barbell

![]()

Safety Tip

Always maintain the natural curve in the lower back while performing this exercise, especially if lifting heavier weight. Do not round the back.

Execution

1. Stand with legs shoulder-width apart, leaning forward at the waist, knees slightly bent, and arms hanging down, clasped to the barbell with a traditional grip, shoulder-width apart.

2. Pull the barbell to the chest, still in a bent position, until your elbows are bent parallel to the chest.

3. Return the weight to the starting position and repeat.

Muscles Involved

Primary: latissimus dorsi, trapezius

Secondary: triceps, deltoid

Running Focus

Muscle imbalances are prevalent in runners, predominantly between the four muscles of the quadriceps group, between the quadriceps group and hamstring muscles, and, more generally, between the legs (left versus right). Muscle imbalances of the upper body are often not addressed in strength training for runners because the practical shortcomings of such imbalances are not assumed to affect running performance. However, an imbalance between the “push” muscles of the chest and the “pull” muscles of the upper back can have a dramatic impact on gait because the forward lean or lack thereof changes the degree of lift the quadriceps group can generate during the forward swing phase. A lack of lift as a result of too much forward lean can inhibit the speed of running, especially during faster-paced training.

The speed not created by the normal lift of the gait cycle can be compensated for with faster turnover, but the resulting emphasis on aerobic capacity because of poor posture can have an adverse effect on performance if the athlete’s aerobic fitness is subpar. Hence, the anatomy of running plays a major role in performance despite its seemingly secondary role in fitness development. Specifically, if a large muscle group is strengthened (e.g., the pectorals through “push” exercises), the agonist muscles (in this case, those of the upper back) must be equally strengthened.

Variation

Wide-Grip Bent-Over Row With Barbell

A wider grip allows you to work the muscle at a different angle. In this case, it does not change the main muscle group worked. Some athletes with longer arms prefer the wider grip because it feels more natural. Maintain the natural curve in the lower back.