Running for pleasure was a long way down the list of priorities that determined how the pelvis would evolve in humans. The bones that form it are principally in place as a protective structure for the developing fetus, a need not shared by men, in whom a narrower pelvis forms the platform from which the legs unite with the rest of the body parts and have developed to accommodate locomotion.

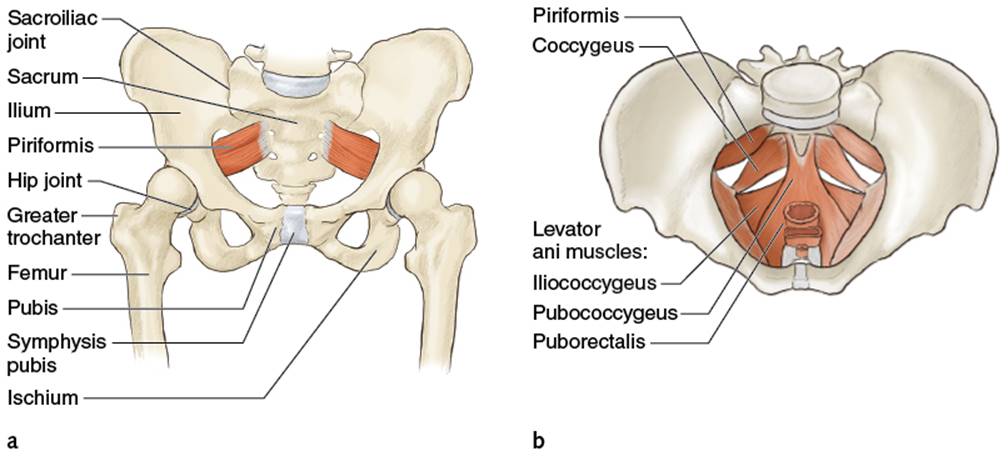

Six major bones form the pelvis, two each of ilium, ischium, and pubis (figure 7.1a). Although these bones are solidly joined to each other with no discernable laxity, each ilium meets the lowest part of the spine, the sacrum, posteriorly at the large sacroiliac joints, where there can be considerable movement. This is most noticeable during childbirth, when hormonal influences cause the ligaments that bind the joint to relax to such an extent that the joint may become subluxed, or partially dislocated, with considerable instability and possible consequences for the female runner. Above the sacrum are the five lumbar vertebrae, which have an important function in keeping the whole skeletal structure stable. As well as these two joints, each pubis is linked at the front by the symphysis pubis at the lowest point of the abdomen. This is a more solid fibrous connection, but sometimes liable to damage in a slip or fall or as a result of chronic overtraining, for it forms the pivot and point of maximum force and corresponding weakness between the legs and torso.

Figure 7.1 Pelvic bones and muscles: (a) bony structures; (b) pelvic floor muscles.

On the side of each ilium is a depression that forms the hip, known as a ball-and-socket joint. Its shape has developed in order to combine maximum stability with the greatest possible range of movement. The shoulder is similar but shallower and has a far greater likelihood of dislocation under load. The head of the femur forms the ball; movement of the joint is limited by the bony surrounds of the acetabulum, or socket, and also by the density and elasticity of the surrounding muscles and tendons.

If the pelvis is viewed from above as an oval-shaped clock, the two sacroiliac joints are fairly close together at the 11 and 1 o’clock areas, the hips at 4 and 8, and the symphysis at the 6 o’clock site. If one of these joints is moved, then another has to change position to compensate. This becomes important when running, for the pelvis is swung from side to side and twisted during the gait cycle, which has an effect on all the structures in and around it.

Forming a floor to the pelvis is the levator ani (figure 7.1b), which, for those with some knowledge of Latin, does just that. It lifts the anus and cradles all the other internal organs that fill the pelvis so that they do not collapse through the pelvic outlet. Weakness of the levator ani will predispose people to degrees of incontinence, and it is a muscle that requires training and toning just like any other. Running increases the pressure inside the abdomen, so any frailty may produce unwanted physical symptoms.

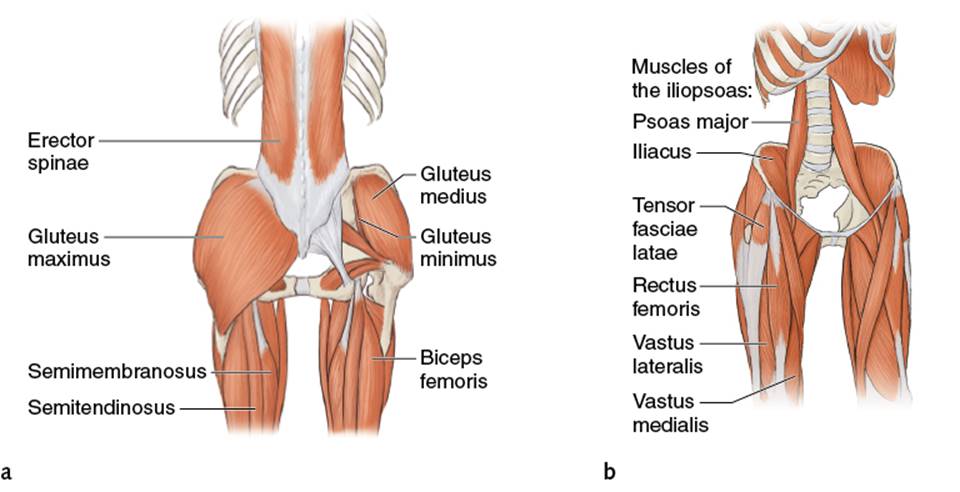

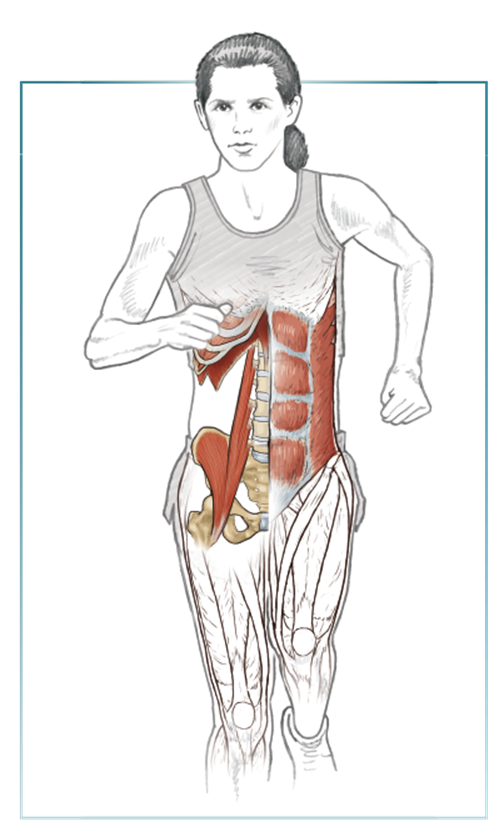

The other pelvic muscles have a dual function to stabilize and move the legs from their pivot at the hip joints. The stability is aided by some large ligaments, which are relatively inextensible, though with good breadth of movement. Running from the lumbar vertebrae and the interior of the ilium are the iliopsoas muscles, which pass through the pelvis, forming soft walls for the internal organs, to the inside of the femur below the hip joint. Over the lumbar vertebrae, they are counteracted by the erector spinae muscles, which stabilize the spine externally. The iliopsoas is a strong flexor of the hip and pulls the thigh up toward the abdomen.

The bulk of the buttock is formed by the glutei, three layers of muscle that slope down the outside of the back of the ilium at 45 degrees. Contraction of the outer layer, the gluteus maximus, extends and rotates the hip joint outward. It continues down the outside of the thigh as the tensor fasciae latae (see chapter 8 for more about this). The gluteus medius and minimus, underneath it, insert into the top of the femur at the greater trochanter, where their action is to pull the thigh outward, known as abduction, with the hip joint acting as a fulcrum.

Runners with low back pain are frequently diagnosed with piriformis syndrome. The piriformis muscle lies alongside the gluteus medius, and pain probably occurs because of its close proximity to and irritation of the sciatic nerve. It both stabilizes and abducts the hip joint.

Because the hip joint is so mobile, there have to be groups of muscles to counteract the forces produced by those that originate around and above the pelvis. These primarily pull the hip backward, abduct, and rotate it outward. The opposing muscles are those of the upper leg, which often have more than one function. The hamstrings— semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and biceps femoris—all arise from the lower pubic bone (figure 7.2) and travel down the back of the thigh and behind the knee joint as its flexor (the lower limbs are discussed in more detail in chapter 8). Their upper leg function is to extend the hip backward. The opposite of abduction is adduction, and the three adductors, magnus, longus, and brevis, together with the gracilis, all pull the thighs together. They arise from the inside of the pubis and are inserted along the inner border of the length of the femur. As well as the iliopsoas, the rectus femoris and the other quadriceps muscles also extend over the hip joint, and when contracted, have a flexing action on the femur.

Figure 7.2 Lower core through upper leg: (a) back; (b) front.

Muscles may be distinct entities, but often merge into one another and when dissected can be difficult to separate. The running action is repetitive, so that muscles with even slightly different functions may oppose each other during the running cycle and actually produce negative frictional forces. Where this may happen, a small fluid-filled sac called a bursa may form, the largest of which is over the greater trochanter, known as a trochanteric bursa. This may become inflamed and sore.

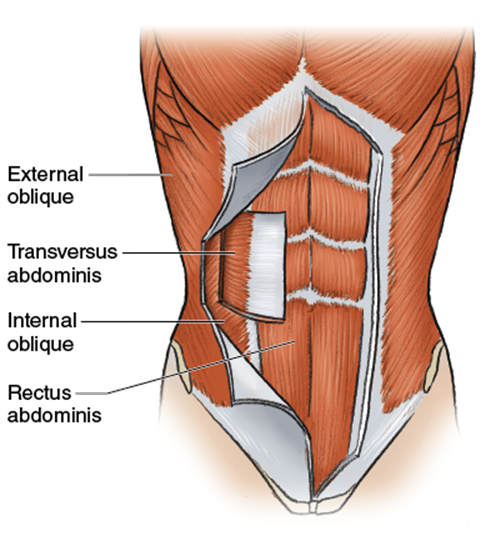

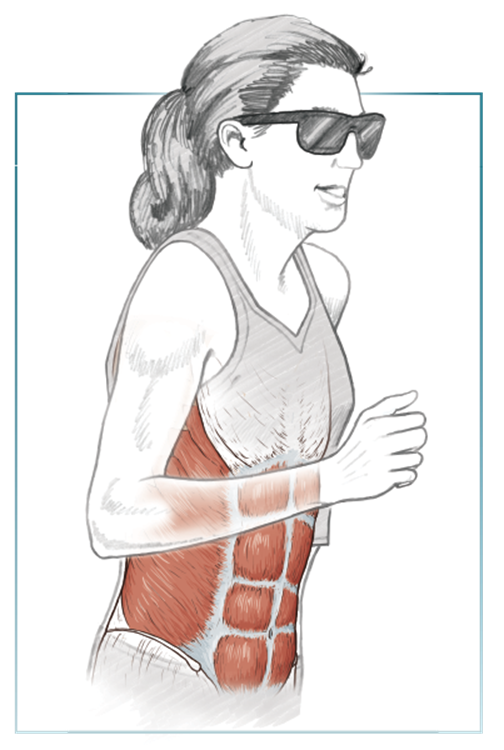

Returning to the pelvis and its adjacent organs, the abdomen, unlike the chest, does not have a bony architecture to stabilize it. The vertical height is maintained by the lumbar vertebrae. The responsibility for stability falls to the abdominal contents, which exert a counterpressure to a surrounding circular wall of muscles formed by the rectus abdominis, which extends from the base of the rib cage centrally down to the pubic symphysis and bone (figure 7.3). Outside this and lying diagonally are the external and internal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles, which have three functions: to abduct and rotate the trunk, to flex the lumbar and lower thoracic vertebrae forward, and to contain the abdomen. When running, these muscles alternately lengthen and shorten as the pelvis moves not only from side to side, but also twists, rises, and falls relative to the surrounding body parts. In addition, they have a function to aid respiration at high rates, working in conjunction with the diaphragm and ribs, which is particularly noticeable if the runner is reduced to panting. Thus, they have multiple roles, all of which may be required at the same time, and will perform better if well and thoroughly trained.

Figure 7.3 Rectus abdominis and surrounding muscles.

Rather than being active exercisers while running, the lower back muscles and lumbar vertebrae have more of a stabilizing passivity. First and foremost, they must maintain an upright posture, tempered by the need to accommodate for hills, where the upper body must lean backward or forward to counteract gravity upending the runner. The encircling musculature must allow rotation, body lean around corners, and lateral movement on any diagonally sloping surface, so they will contract and expand to maintain this stability. These complex movements have to coexist in conjunction with all the other variations in posture that occur as the legs move, the lungs breathe, and the abdominal contents shift to accommodate ingested fluid and nutrients during the run. Intrinsic strength, particularly of the muscles that surround the lumbar vertebrae, should be considered an essential in every runner because any weakness is liable to escalate into other areas.

Specific Training Guidelines

For the core exercises that require the movement of body weight only, multiple sets can be performed with many repetitions. All body-weight exercises should be slow and deliberate. Without extra resistance, the emphasis should be less on moving weight and more about perfect movement.

High repetitions are a great way for a runner to develop muscular endurance, which benefits long-distance runners; however, strength development to aid power only comes from using heavier resistance. Choosing what weights to use (when applicable) and how many or how few repetitions are to be performed is a function of the goal of the workout, and in the macro sense, the performance goal of the runner.

Core exercises should be performed at all stages of the training progression. Since many are body-weight bearing only, requiring no additional load, they can be performed three or four times per week.

![]()

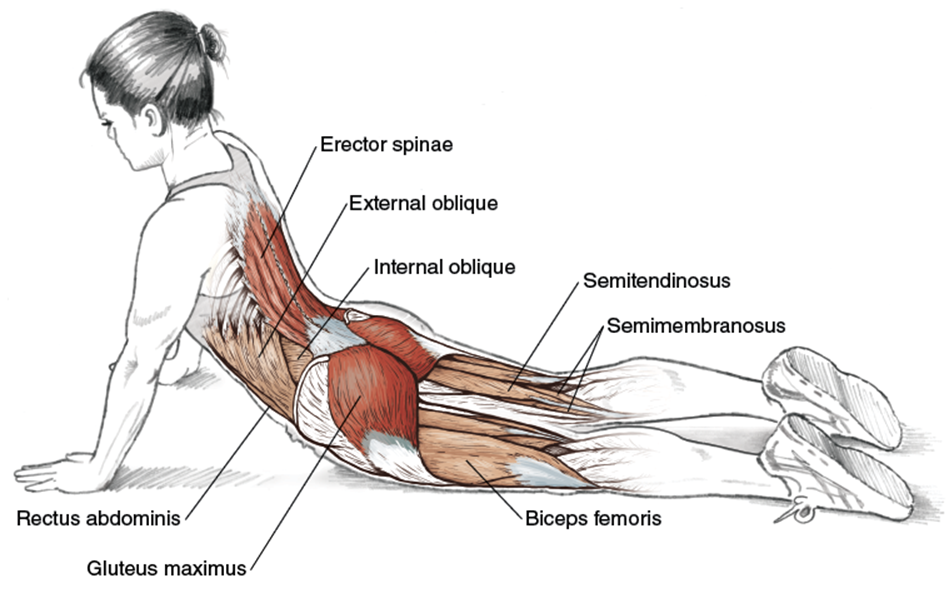

Back Extension Press-Up

Execution

1. Lie prone on the ground with arms in the push-up position and legs outstretched. Keep the body rigid and in a straight line.

2. Press up the arms only until the torso is off the ground. Hold this position for 10 to 15 seconds, breathing throughout.

3. Lower the arms, bending at the elbows, and return to the original position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: erector spinae, gluteus maximus

Secondary: hamstrings, rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique

Running Focus

This a very simple exercise to perform. Not to be confused with a synonym for the push-up, the press-up extension of the lower back helps strengthen the muscles and tendons of the erector spinae, and acts as the antagonist for the rectus abdominis muscle. This exercise both strengthens and stretches the support structure of the sacral and lumbar spine, helping the pelvis rotate and twist properly, and mitigating the forward tilt of the pelvis if too many abdominal strengthening exercises have been performed, leading to an imbalance between the abdominals and muscles of the lower back.

Unfortunately, an emphasis on the core exercises can become an emphasis on the abdominals, with little attention paid to the muscles of the lower back and the glutes. Without strong glutes and a supportive lower back, the hamstrings often can’t generate sufficient muscular power despite their having been strengthened properly. Essentially, the strongest muscles are only as strong as the weakest link on the kinetic chain allows.

The proper movement of the pelvis is critical in the gait cycle. A misalignment of the pelvis due to muscle imbalances between the abdominal muscles and the muscles of the lower back can cause injuries that impede running performance despite good cardiothoracic fitness.

![]()

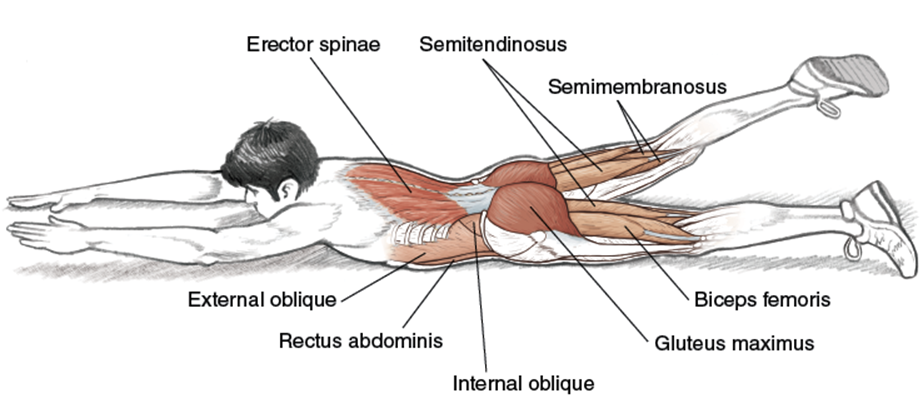

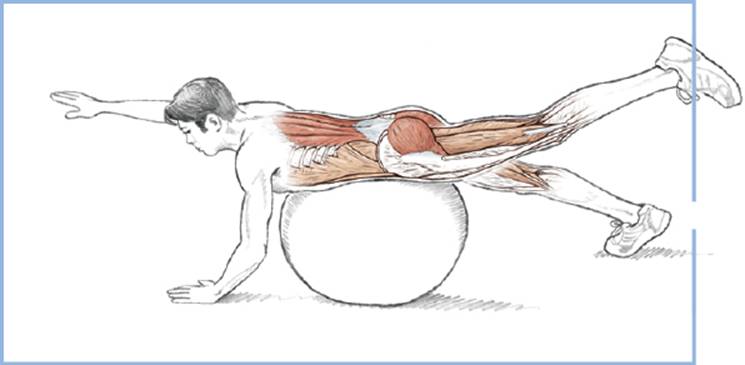

Lumbar Hyperextension/ Alternating Arm and Leg Raise

![]()

Safety Tip

Performing this exercise requires hyperextension of the back. Normally, this is not a problem, but for runners with chronic back pain or disc issues, press-ups are safer.

Technique Tips

•This exercise can also be performed on a Roman chair, where gravity plays a greater resistance role. Because Roman chairs are rarely around when you need them, performing this exercise on the ground works as well.

•All the movement should be generated by the muscles of the lower back and glutes.

Execution

1. Lie prone on the ground with arms and legs outstretched. Keep the body rigid and in a straight line.

2. Raise the left arm and the right leg three to four inches off the ground. Hold this position for 10 to 15 seconds, breathing throughout.

3. Lower the left arm and right leg, and raise the right arm and left leg simultaneously.

Muscles Involved

Primary: erector spinae, gluteus maximus

Secondary: hamstrings, rectus abdominis, external oblique, internal oblique

Running Focus

Lumbar hyperextensions can be performed in many ways. The goal of the lumbar extension is to strengthen and stretch the muscles of the lower back, glutes, and, to a lesser extent, the abdominals to help provide the appropriate pelvic tilt during the running gait cycle. A misaligned pelvis causes a chain reaction of misalignment, resulting in poor running form and wasted energy. Not only do the muscles of the back, abdominals, and glutes have to work in unison, but they also must work to balance each other and still generate enough strength to perform the exercise. This is very similar to how the core works when running. Because the pelvis is rotating and twisting, the core must dynamically stabilize, reacting to terrain shifts, turns, and missteps.

Variation

Lumbar Hyperextension on Physioball

Using a physioball changes the dynamic of the lumbar hyperextension. By only using one hand for balance (and, after mastery, no hands), there is a neuromuscular (proprioceptive) component added to the exercise. Ultimately, the goal of this exercise is to not include a balance hand. Balance can be maintained on the physioball from mastering the form of the exercise and strengthening the muscles of the core so that they can be activated when needed. Runners tend to overlook proprioceptive exercises because there is not much visible effort, rather small, subtle movements that help create more fluid running.

![]()

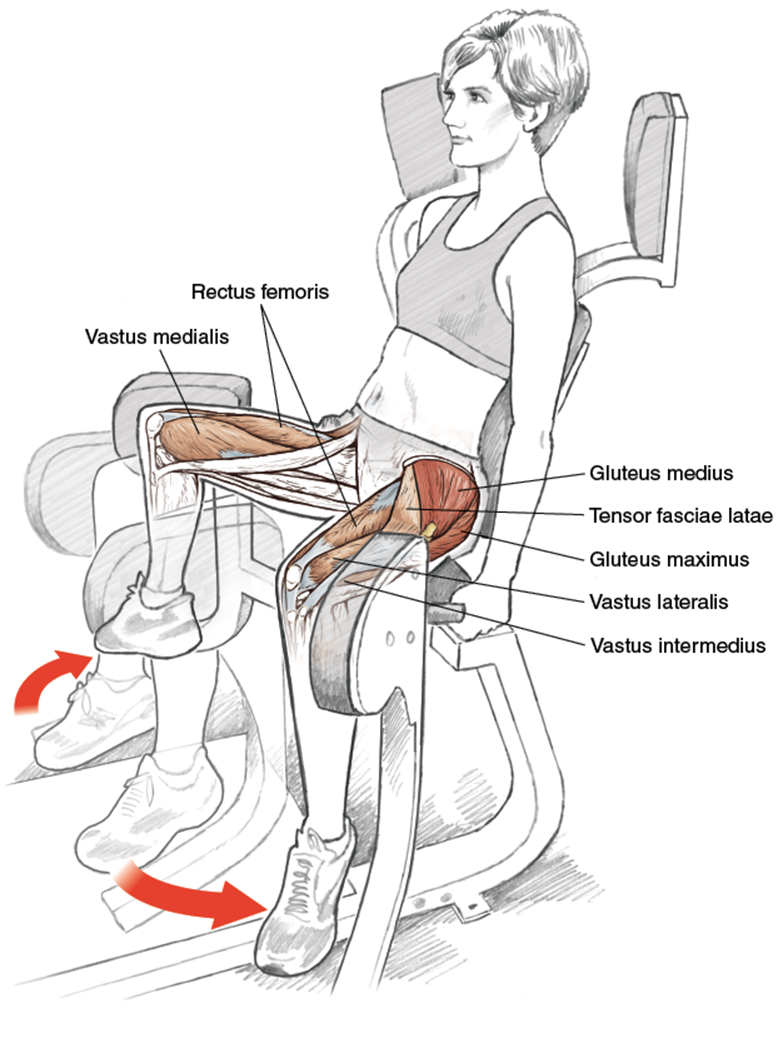

Hip Abductor Machine

Technique Tips

•The motion should be fluid, but with consistent effort throughout.

•The more upright the backrest, the more the emphasis on the gluteus medius.

•Avoid trying to overextend the exercise. Don’t force the legs higher laterally than your hip naturally allows. Focus on pressing the legs apart using only the targeted muscles of the gluteus.

Execution

1. Sit in a proper seat position, with machine pads on the outsides of the knees.

2. Press outward using the abductor muscles (outsides of the legs). Emphasize reaching a full range of motion.

3. Return to the original position by gradually resisting the weight.

Muscles Involved

Primary: gluteus medius, gluteus maximus

Secondary: tensor fasciae latae, quadriceps

Running Focus

The abductor exercise can be done during the same workout as the adductor exercise; it is easy to change the pad positions on the machine, but its emphasis on the glutes makes it a better fit with the exercises for the glutes and lower back. Many runners, especially those who underpronate, complain of piriformis pain at some point in their running careers. Because of its location, the piriformis muscle is difficult to stretch. However, abduction exercises aid in preventing and treating piriformis pain and sciatica by stretching and strengthening the gluteus medius, which is connected.

![]()

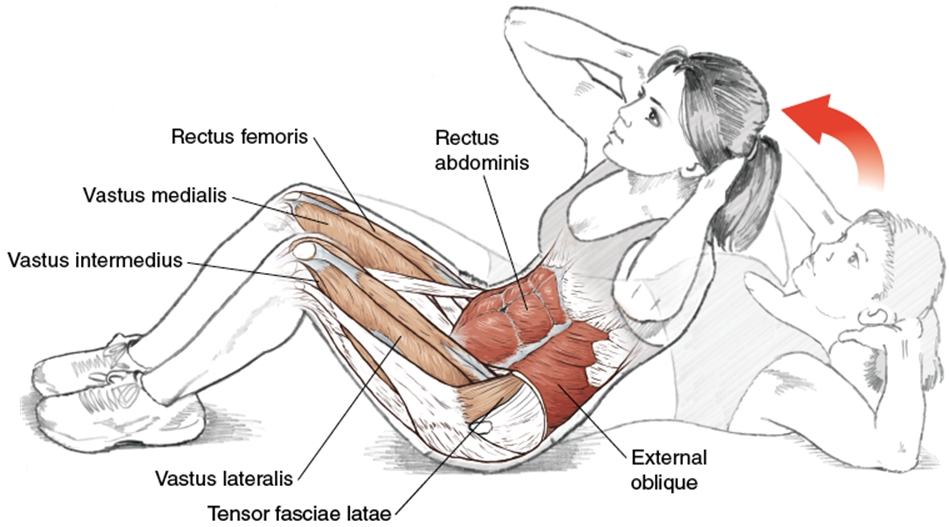

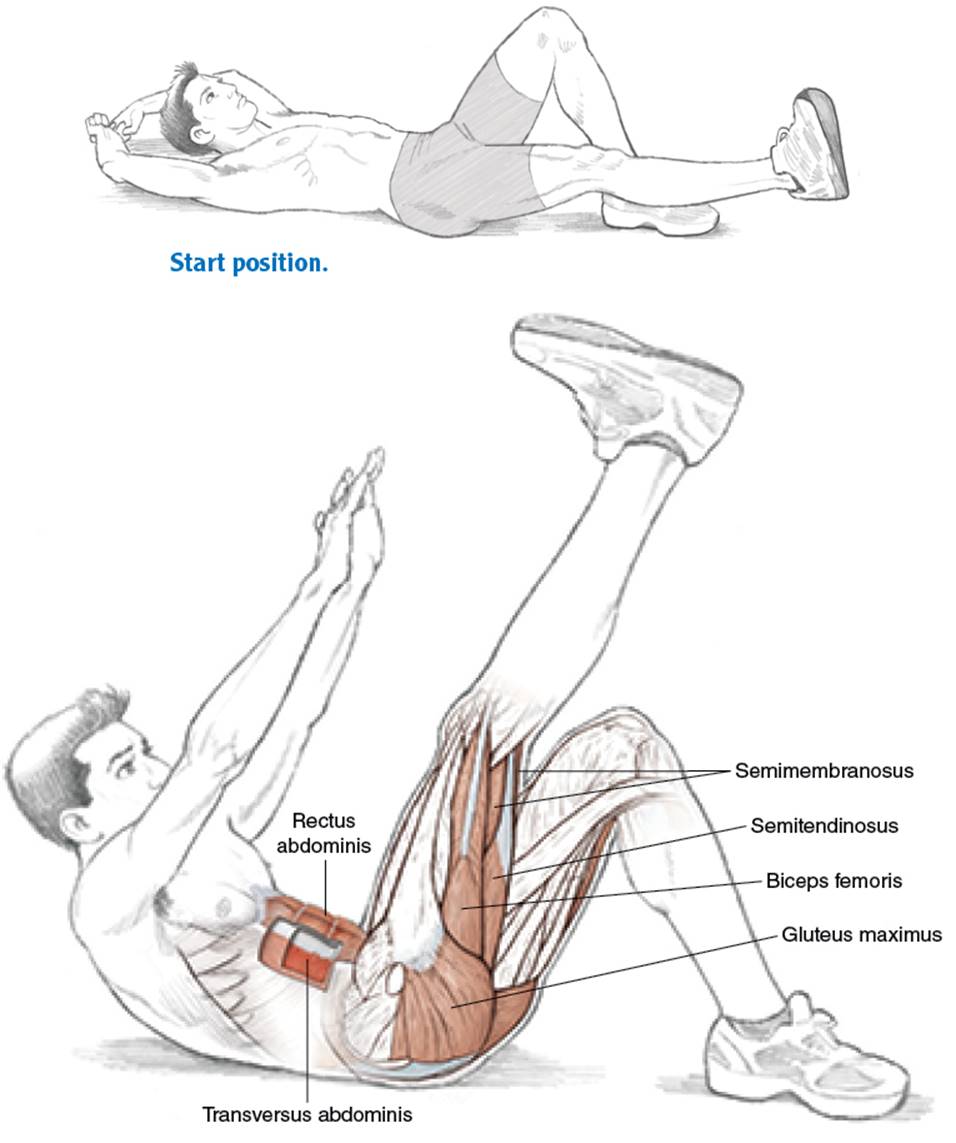

Floor Sit-Up

Execution

1. Lie on the back with knees steepled, feet pressed to the floor, and hands gently touching the back of the head, but not clasped.

2. Raise the torso by rounding the back one vertebra at a time while pressing the pelvis down to floor. Raise the torso only 45 degrees before lowering the back to the floor.

3. Inhale, and gradually lower the torso to the floor one vertebra at a time.

Muscles Involved

Primary: rectus abdominis, external oblique

Secondary: quadriceps, tensor fasciae latae

![]()

Safety Tip

Don’t clasp, but gently touch the hands behind the head because it is easy to pull the head and torso up by using the muscles of the arms.

Technique Tip

•Sit-ups can be performed with a partner holding down the feet of the person performing the exercise. It makes the exercise easier, but allows more reps to be performed.

Running Focus

Because the quadriceps and hamstrings counterbalance each other, so do the muscles of the abdominals and lower back. To avoid muscle imbalances and potential injury, it is important to perform abdominal exercises after performing the strength-training exercises for the lower back described in the first part of this chapter. The sit-up should not be performed for speed, but in a relatively quick, fluid manner. The lowering of the torso should be done slowly, with attention to the work the abdominals are doing.

The rectus abdominis is the dominant muscle affected by sit-ups. It controls the flexion of the abdomen. Because almost all abdominal exercises work the rectus abdominis, a single set to failure can make up the start of an abdominal set.

The proper movement of the pelvis is critical to the gait cycle. A misalignment of the pelvis due to muscle imbalances between the abdominal muscles and the muscles of the lower back can cause injuries that impede running performance despite good cardiothoracic fitness.

Variation

Oblique Twist

A simple variation on the sit-up involves twisting the torso using the oblique muscles by attempting to touch the elbow to the opposite hip. A set of 12 can be done all on one side and then the other, or each rep can alternate sides.

![]()

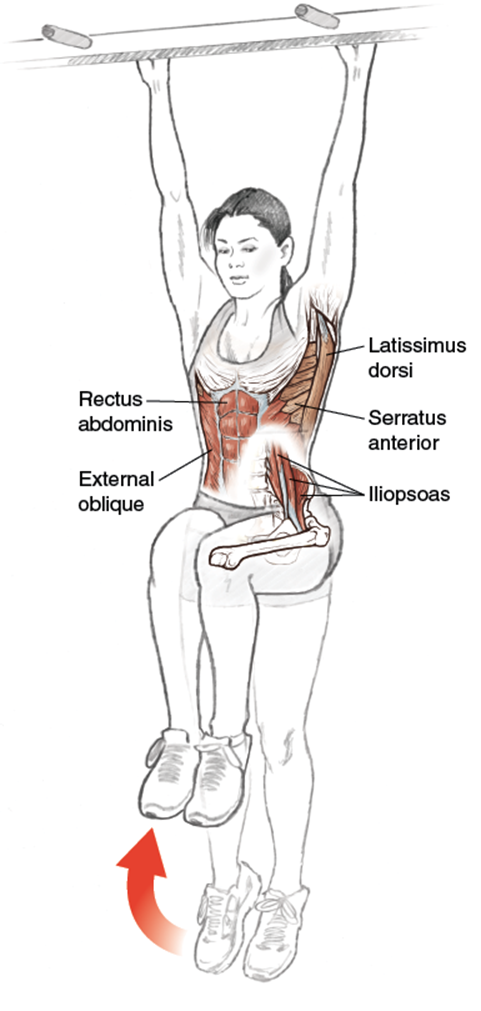

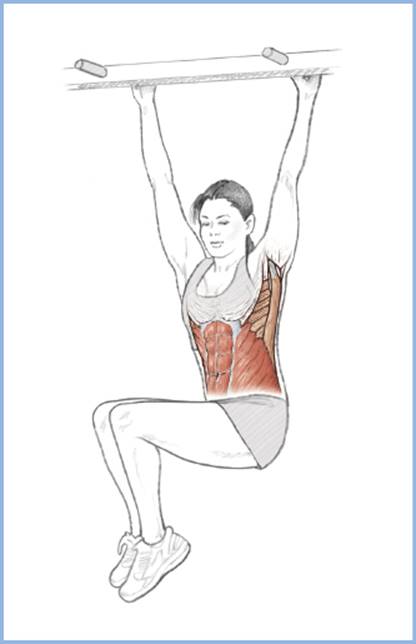

Hanging Leg Raise

![]()

Safety Tip

This exercise can put a lot of stress on the shoulder. Limit the number of reps if the shoulder is compromised.

Execution

1. Hang from a pull-up bar with palms facing forward. Emphasize lengthening, feeling gravity exerting its force on your spine.

2. Using a controlled movement, bring the knees up toward the chest. Keep the torso from swinging.

3. Gradually return to full extension and continue to repeat.

Muscles Involved

Primary: rectus abdominis, external oblique, iliopsoas

Secondary: latissimus dorsi, serratus anterior

Running Focus

The hip flexor muscles, specifically the iliopsoas, fatigue greatly during the course of a long run or race on a course that has the same terrain throughout. The repetitive nature of running is exacerbated with few terrain changes, and smaller muscles fatigue quickly. By strengthening the iliopsoas and the other hip flexors, runners can delay the onset of this fatigue. Also, when the terrain is hilly, requiring a lot of lifting throughout a run, weaker muscles will fatigue quicker, and gaining solid footing becomes harder.

Variation

Hanging Leg Raise With Twist

The standard hanging leg raise affects the external and internal oblique, but adding a twist to the side increases the role of these abdominal muscles that are responsible for rotation and lateral flexion of the torso. As was mentioned in the introduction to this chapter, the oblique muscles help to twist, allowing for terrain adjustments, and they aid respiration by working in conjunction with the diaphragm and ribs.

![]()

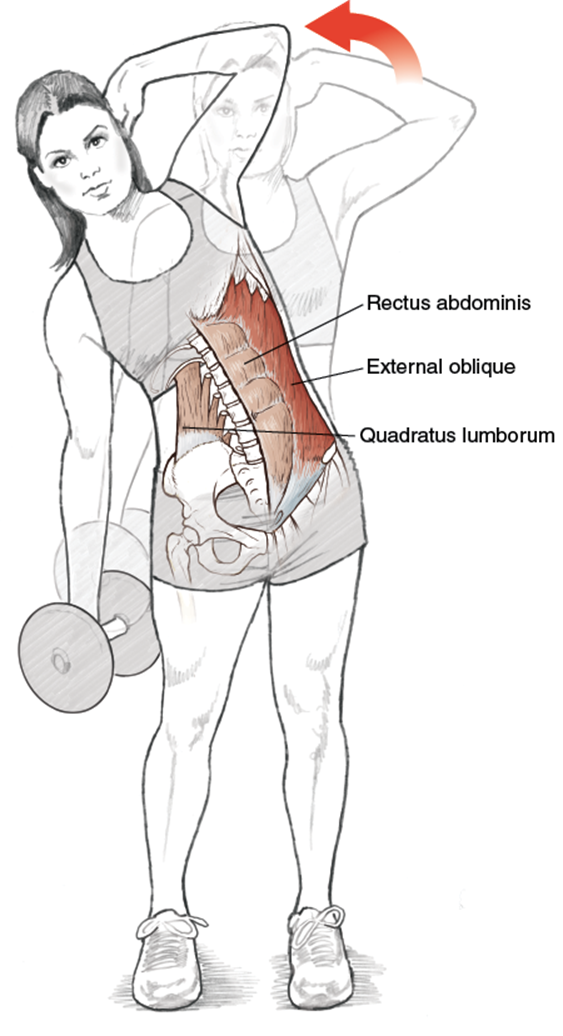

Dumbbell Side Bend

Execution

1. Stand with good posture, feet shoulder-width apart. Hold a dumbbell in one hand with the arm extended downward. The other hand is placed behind the head with the elbow out.

2. Bend at the waist in the direction of the hand holding the dumbbell, allowing the weight to pull the side down gradually.

3. Complete a set of 12 reps and then switch the dumbbell to the other hand and repeat.

Muscles Involved

Primary: external oblique

Secondary: rectus abdominis, quadratus lumborum

Running Focus

Balancing the abdominal muscles is the goal of this exercise. Most abdominal exercises focus on the large muscle of the abdominals, the rectus abdominis. The side-to-side movement of this exercise helps develop the external oblique, also strengthened in the hanging leg raise with twist. The strengthening of the external oblique helps minimize the side-to-side listing at the end of a fast race or hard effort in a speed workout. Because the smaller muscles of a large muscle group—that is, the abdominals—fatigue easier than the large rectus abdominis, it is important to do exercises that specifically target the smaller muscles so that they maintain their relative strength and do not become dominated by the larger muscle.

The practical application of this exercise is to eliminate the side-to-side rocking of the upper body during the gait cycle. While a leg length discrepancy could cause this rocking, the usual culprit is poor abdominal strength, especially weak oblique muscles. The inability of the abdominal muscles to maintain erect posture causes an awkward side-to-side motion generated by a pelvis that is not aligned.

![]()

Single-Leg V-Up

Execution

1. Lie flat on the back with your hands reaching back behind your head. One leg is steepled and the other is raised approximately six inches off of the ground.

2. Leading with the chin and chest, engage the abdominals, raising up as in a sit-up, but also raise the leg that is off the ground, meeting the hand at its apex.

3. Recline to the initial position.

Muscles Involved

Primary: rectus abdominis, transversus abdominis, iliopsoas

Secondary: hamstrings, gluteus maximus

Running Focus

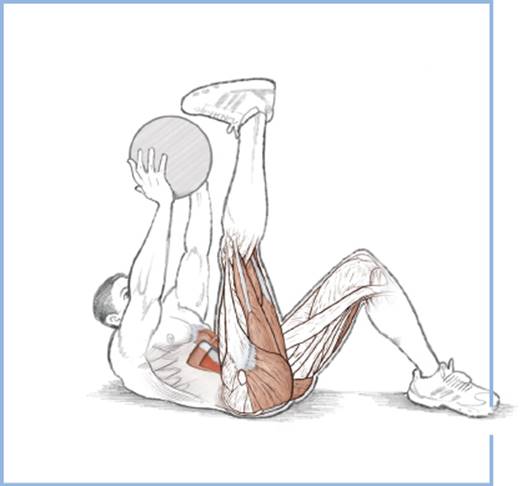

This exercise is dynamic and quickly fatigues the abdominal muscles and the iliopsoas. Because of the incorporation of both the upper body and lower body, there is more of a whole-body movement that more closely resembles a running movement than some of the other exercises in this chapter. Performed to failure, this exercise and its variation with a medicine ball can be an entire abdominal workout, especially if done as the final exercise in a strength-training session.

Variation

Single-Leg V-Up With Medicine Ball

The use of the medicine ball works the abdominals harder because of the added weight. Since the medicine ball is held away from the abdominals, even a five-pound ball feels heavy as a result of its distance from the fulcrum (the abdominal muscles). Also, the coordination of the movement with the added weight helps develop coordination, a skill not gained when just running in a forward motion.