STUDY HINTS

Errors in mitosis and meiosis can lead to aneuploid cells, that is, to cells that have more or fewer chromosomes than the normal diploid (the euploid, or literally “true multiple”) set of chromosomes. Because so many genes are involved in this change in the genetic makeup of a cell, most aneuploids die or are very abnormal. Among those that do survive, however, the addition of a chromosome is apparently more readily tolerated than is the loss of a chromosome.

A related type of genomic change is polyploidy, in which fusion of meiotic products, multiple fertilization, or defects in spindle formation result in extra complete sets of chromosomes (3n, 4n, and so forth). Although polyploidy can occur in either animals or plants, it is much more common in plants. Indeed it is an important evolutionary mechanism in plants that can yield new species. It is also a valuable tool of plant breeders who want to combine characteristics from separate but related species for agricultural purposes. Seedless polyploids are also economically useful.

It is useful to distinguish two types of polyploidy. Autopolyploidy (auto- means “self”) occurs when an inhibition of normal meiosis or other processes increases the number of chromosome sets within a single species. For example, species A (where 2n = AA) becomes an autotriploid (3n = AAA), autotetraploid (4n = AAAA), or higher multiple. Allopolyploidy (allo- means “different”), on the other hand, combines chromosome sets from different species. For example, the allotetraploid between species A (2n = AA) and species B (2n = BB) has the chromosome makeup 4n = AABB. Since allopolyploids probably originate from meiotic errors in rare F1 hybrids between two species (2n = AB), it is probably less common than autopolyploidy.

The predictions of viability and phenotypic change find a special case in the X chromosomes of mammals, where X-chromosome inactivation (producing a Barr body) is a normal mechanism to balance the dosage of X-linked genes in males and females. Males have one X chromosome, whereas normal females have two. To balance the gene dose of X-linked loci, one X chromosome in females becomes condensed (is hetero-chromatinized) and the vast majority of X-linked genes are inactivated. In cells with an extra X chromosome, this inactivation mechanism minimizes the deleterious effects associated with such a major genomic change. Consequently, in humans, for example, many sex-chromosome aneuploids may survive with various levels of phenotypic abnormality. People with Turner’s (XO) and Klinefelter’s syndromes (XXY) are examples of this mechanism. In contrast, most autosomal aneuploids die.

In addition to variations in chromosome number, changes in chromosome structure also have wide-ranging effects, from altering linkage relations to yielding inviable gametes. There are four basic types of chromosome aberrations. Three of these (inversion, deletion, and duplication) involve changes within a chromosome, whereas the fourth (translocation) occurs when a chromosome segment moves to a nonhomologous chromosome. The four most common types of changes in chromosome structure are illustrated in the following outline.

I. Inversion

A. Paracentric inversion (both breaks are in the same arm)

B. Pericentric inversion (the centromere is included within the inversion)

II. Deletion

III. Duplication

IV. Translocation

Careful study of the four major types of chromosome aberrations will let you see what changes in linkage will occur with each. Inversions change the order of genes in a linkage group, and if the centromere is included (i.e., pericentric inversion) it will also change chromosome appearance. Except for point mutations that might occur at the break points, the major consequence of an inversion is the production of duplications and deletions that can occur by crossing over in inversion heterozygotes.

Duplications and deletions (or deficiencies) add or subtract genes from a genome and thus lead to genetic imbalances. Such aberrations commonly result in serious developmental defects or early death of the carrier.

Translocation is the only one of these four structural changes that involves two different nonhomologous chromosomes. A reciprocal translocation is the exchange of fragments between two linkage groups, and as long as both translocated chromosomes segregate into the gamete, the genome will be complete. When translocated and normal chromosomes segregate together, however, gametes with duplicated or missing chromosome segments can be produced. As noted previously, these generally result in death of the zygote.

IMPORTANT TERMS

Acentric

Allopolyploidy

Amphidiploid

Aneuploidy

Autopolyploidy

Barr body

Centric fusion

Chimera

Deletion

Dicentric

Dosage compensation

Down syndrome

Duplication

Euploidy

G-branding

Gynandromorph

Inversion

Isochromosome

Karyotype

Klinefelter syndrome

Monoploid

Monosomic

Mosaic

p arm

Paracentric inversion

Pericentric inversion

Polyploid

q arm

Reciprocal translocation

Telomere

Tetraploid

Translocation

Triploid

Trisomic

Turner syndrome

PROBLEM SET 16

1. A polyploid series of related plant species has chromosome numbers of 18, 27, 36, 45, 63, and 72. What can you say about the genetic relationship of these plants based solely on chromosome number?

link to answer

2. In humans, trisomic individuals are most likely to survive if they are trisomic for what kind of chromosome?

(a) a large autosome,

(b) a medium-sized autosome,

(c) a sex chromosome.

link to answer

3. Do you think it is possible to cross the cocoa tree with the peanut, treat the sterile F1 plant with colchicine to double the chromosome number, and obtain an allopolyploid that will produce chocolate-covered peanuts? Assume this is a serious question from a nongeneticist and explain your answer.

link to answer

4. Assume an allopolyploid with two unrelated 2n parent species: D with a 2n number of 18, and G with a 2n number of 14. If the allopolyploid is crossed back to species D and forms a viable plant, what would you expect to see at synapsis during the first prophase of meiosis? What is your answer if the hybrid is crossed back to the species-G parent?

link to answer

5. Acentric and dicentric crossover chromosomes result from a single exchange within the loop of a

(a) paracentric inversion heterozygote or

(b) pericentric inversion heterozygote.

link to answer

6. Changes in chromosome structure can complicate otherwise innocent-looking problems. Consider the following set of data on the results of a testcross of a hybrid for five sex-linked loci in Drosophila melanogaster.

The standard map distances for these loci, which are taken from the literature, are as follows:

(a) First diagram the standard linkage map and the map derived from the recom-binational data.

link to answer

(b) Propose an explanation for any discrepancy between the two maps.

link to answer

link to answer

7. Translocation heterozygotes have reduced fertility because of the unbalanced (aneuploid) products of meiosis that come from adjacent segregations. However, some of the aneuploid products of meiosis, although producing lethal or detrimental aneuploid progeny when combined with euploid gametes from a normal individual, can still produce euploid progeny when combined with aneuploid gametes from the same translocation heterozygote. How do you explain this? This phenomenon is seen more frequently in animals than in plants. Why?

link to answer

8. Two diploid plant species, A and B, are closely related, whereas diploid species C is unrelated to A and B. If you were to be given allopolyploids of A × B, and of A × C, in what ways might they differ from each other

(a) in appearance?

link to answer

(b) in karyotype?

link to answer

(c) in fertility?

link to answer

link to answer

9. One sometimes finds successful hybrids between two different species in which the hybrid contains only a monoploid set of chromosomes from each parent. What reasonable conclusion(s) can you come to about these hybrids?

link to answer

10. An autotetraploid has 48 chromosomes. How many linkage groups does it have?

link to answer

11. An allotetraploid has 48 chromosomes. How many linkage groups does it have?

link to answer

12. The giant polytene chromosomes of Drosophila have banding landmarks that can be used to identify changes in chromosome structure. In the following sketch, we show two regions of a polytene chromosome (2D and 2E), with individual bands numbered within each region. Assume that we are studying four different chromosomes that are deficient for a small number of bands. The deficiencies are listed next to the diagram. In addition, all of the chromosomes behave as if they are deficient for r locus. From the information given, what can you conclude about the bands with which the r locus must be associated?

link to answer

13. The following diagram shows a section of Drosophila salivary gland chromosome and the extent of four deletions. Def-1 is genetically deficient for the genes p, l, and m; Def-2 is deficient for p, m, t, and l; Def-3 for n, b, and v; and Def-4 for n and b. What band or bands include the location of the t gene?

link to answer

14. What are the expected chromosome constitutions of the products of mitosis and meiosis of a trisomic (2n + 1) cell?

link to answer

15. Assume that a cross of species I (AABBCCDD) with species II (EEFFGGHH) produces a vigorous though sterile hybrid (ABCDEFGH). Is it possible to produce a hybrid between species I and II that is fertile at the time it is formed?

link to answer

16. The chromosome structure of the ancestral species is labeled A in the preceding diagram. Indicate the evolutionary relationships for each of the species (B through F), and the mechanism(s) by which each species became chromosomally distinct.

link to answer

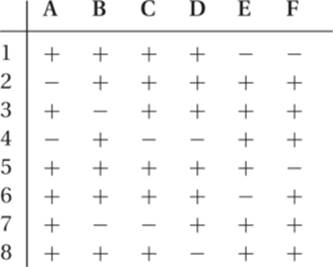

17. The data in the following table are the hypothetical results of crosses between five known mutations (a through e) and 6 deletions (1 through 6). The results are indicated by a plus (+) for complementation and a minus (−) for lack of complementation.

(a) Determine the linear sequence of the mutations.

link to answer

(b) Diagram the deletions relative to the mutant sequence.

link to answer

link to answer

18. Please draw a bivalent from a cell in meiosis that is heterozygous for a small deletion. Please draw a bivalent that is heterozygous for a small duplication. If you were shown a bivalent and not told what kind of chromosomal mutation was involved, how could you tell whether it was a duplication heterozygote or a deletion heterozygote?

link to answer

19. The following diagram is a section in the middle of a polytene chromosome of Drosophila used for deletion mapping.

Four deletions are isolated that remove parts of this chromosome and that allow expression of the recessive gene p when heterozygous. Assume the chromosome map continues to the left and to the right following the same nomenclature. The four deletions are 85D9—87A3, 85E3—87B10, 84A1—86A1, and 85E1—86B2. In which band or bands is the p gene located?

(a) 86A2—86B2;

(b) 85E3—86A1;

(c) somewhere to the right of 86A2;

(d) 85D9—85E2;

(e) none of the above.

link to answer

20. As in the previous question, four deletions have been found that allow expression of the recessive t gene in heterozygotes: 30E6—31B4; 30F5—32B1; 31A4—31C1; and 30F3—31B1. In which band or bands is the t gene located?

link to answer

21. The deletion map below shows eight deletions along a chromosome. Six (A–F) point mutations were tested against these eight deletions for their ability to complement. A plus (+) corresponds to complementation while (−) indicates a lack of complementation. Determine the order of the genes on the chromosome.

link to answer

ANSWERS TO PROBLEM SET 16

1. The plant with 18 chromosomes is probably the diploid (2n) originator of the series. The monoploid number is then 9, and the other species are all multiples of the basic set of 9 chromosomes. The species with 27 chromosomes, for example, is a triploid (3·9 = 27). Corroboration of this conclusion could be obtained by examining the chromosomes in a karyotype preparation.

2.

(c) A sex chromosome. Lethality in trisomics appears to be associated with gene imbalance, and the larger the autosome, the more genes it probably carries and the greater the genetic imbalance. Those trisomics that survive are generally those that involve the smaller chromosomes. The phenomenon of dosage compensation, which turns off all but one X chromosome in each cell, permits survival of XXX individuals.

3. Probably not. The two genomes have to work together to produce a viable plant. It is extremely unlikely that a small tree and a peanut plant will have compatible developmental systems that would permit formation of a hybrid, but if the two genomes were compatible, the probability that the allopolyploid would exhibit the economically favorable traits of each parental species is probably very small. Our example is a bit whimsical, of course; a better one would be Karpechenko’s Raphanobrassica. In a cross between a radish and a cabbage, the fertile allopolyploid had neither the root of the radish nor the head of the cabbage. This may well have contributed to Karpechenko’s death, since he was a Russian Mendelian geneticist who did not accept T. Lysenko’s Lamarckian concept of inheritance. Lysenko’s ideas were supported as Marxist orthodoxy by the Soviet government, and Karpechenko’s refusal to substitute dogma for science led to his arrest in 1940. He later died in prison. If the hybrid had been successful, his future might have been quite different.

4. Species D has nine pairs, and species G has seven pairs of chromosomes. Since the genetic content of D and G chromosomes is different, the allopolyploid will have nine D pairs and seven G pairs. It will form gametophytes with nine D univalents and seven G univalents, whereas the D parent will form gametophytes with nine D univalents. The hybrid will have nine pairs of D chromosomes and seven unpaired G chromosomes, so that synapsis will show nine bivalents and seven univalents. If the allopolyploid is crossed back to the G parent, at synapsis the hybrid will show seven bivalents (GG) and nine univalents (D).

5.

(a) Paracentric. Whether the inversion is paracentric or pericentric, both are duplicated and deficient for the regions on either side of the inversion (A and C, the complementary crossover strands) and are euploid for the inverted region (B). If the inversion is pericentric, the centromere is in the inverted portion (B), and both crossover products will have a centromere. If the inversion is paracentric, one of the crossover strands will be dicentric, and the other will be acentric (see the accompanying figure).

6. The greatest distance is between y and sn, so we can conclude that these are at either end of the region being tested. If we start with y (assume that y is at zero on the chromosome map), the sequence can be ascertained by adding those genes that are most closely linked:

(a) The standard map is

(b) Since the total number of flies is 1,000, the map distances can be calculated easily, as we described in Chapter 12. Map distances are

The crossover data must therefore have come from an individual that is homo-zygous for an inversion in which the breaks are between spl and rb, and between cv and sn:

7. Each type of alternate segregation in a translocation heterozygote produces two complementary deficiency/duplication gametes (or gametophytes), with one normal and one translocated chromosome. If two such complementary aneuploid gametes (gametophytes) join, a euploid translocation heterozygote is produced. The only way an aneuploid gamete or gametophyte can give rise to a euploid zygote is for the gamete to join with the complementary deficiency/duplication gamete. An aneuploid gamete plus a euploid gamete always yields an aneuploid zygote. This phenomenon is found much more frequently in animals, since their gametes can function even if extremely aneuploid, probably because there is little or no need for gene function in these cells. In plants with alternation of generations, however, we find that the monoploid generation (gametophytes) must function. For example, genes of the male gametophyte (the pollen tube) are active. This results in the loss of many aneuploid gametophytes.

8.

(a) The A × B allopolyploid plants would probably resemble their closely related parents, whereas the A × C hybrids would probably show a greater departure in appearance from both of the parental species.

(b) The A × B allopolyploid would have a 2n set of A chromosomes and a 2n set of probably similar B chromosomes (AA + BB), whereas the A × C allopolyploid will have a 2n set of A chromosomes and a 2n set of dissimilar C chromosomes (AA + CC). The AA + BB individuals might resemble autotetraploids, at least for some of their chromosomes. The AA + CC individuals, with very little likelihood of homology between the A and C chromosomes, would probably appear to be normal diploids when their chromosomes were examined.

(c) Assuming that flower development in the two allopolyploids is normal (that is, the A + B genomes and the A + C genomes both cooperate in the development of normal flowers), the AA + BB plants might well be less fertile than the AA + CC plants. The latter would have normal pairing of homologous A chromosomes with each other and of homologous C chromosomes with each other, leading to normal disjunction and to euploid gametophyte nuclei. The AA + BB hybrid, on the other hand, would most likely have pairing potential for four more or less homologous chromosome sets, which can interfere with the normal segregation of homologous chromosomes. Some normally monoploid gametophytes might then be disomic for some chromosomes, with the complementary products being nullisomic. This often leads to inviable or poorly viable male gametophytes and/or the next generation of sporophytes. This would result in reduced fertility of the AA + BB allopolyploids.

9. They are most likely plants that reproduce by vegetative propagation. The maintenance of this chromosome constitution is no problem in mitosis, but in meiosis the absence of chromosome pairing partners would lead to excessive aneuploidy and sterility. For this reason, the hybrids are very unlikely to be animals, since most animals reproduce sexually and undergo meiosis. Furthermore, most animal monoploids develop abnormally. Alternatively, the chromosome sets are very similar and allow extensive pairing during meiosis.

10. If the autotetraploid has 48 chromosomes, the diploid has 24, and the monoploid chromosome number is 12 (48/4). Since the number of linkage groups is equal to the number of monoploid chromosomes (i.e., the number of chromosomes in the basic set), the number of linkage groups is 12.

11. Another name for allotetraploid is amphidiploid (double diploid). It follows then that all chromosomes occur as pairs (diploid) and that the monoploid number for the allopolyploid is 48/2 = 24. The number of linkage groups is therefore 24. It makes no difference how many chromosome pairs are contributed by each original parent. For example, if species A has a chromosome number of 2n = 30 and species B is 2n = 18, species A contributes 15 linkage groups and B contributes 9. If both are 2n = 24, each contributes 12. In all cases, the sum is 24.

12. The extent of each deficiency has been drawn on the following diagram. The bands that are shared are those that must include the r locus, since each

deficiency also uncovers this mutation. The r locus is therefore in band 2E3, -4, or -5.

13. Since Def-1 is not deficient for gene t, t must be to the right of band 4. Def-2 is deficient for t, showing that t must be located in band 5, 6, or 7. Neither Def-3 nor Def-4 uncovers the t gene; that leaves only band 5.

14. In mitosis, each chromosome behaves individually, and each is expected to divide, with sister chromatids going to each pole, so that all mitotic products will be 2n + 1, just as in the original cell. In meiosis, although the paired chromosomes segregate from each other and go to opposite poles, the unpaired extra chromosome tends to move at random to one or the other pole. The expectation is that half of the meiotic products will have 1n chromosomes, and the other half will have 1n + 1 chromosomes.

15. Yes. It can be done by first making autotetraploids of species I and II by treating the diploids with a spindle poison such as colchicine. Although autotetraploids produce some sterile gametophytes, as a result of aneuploidy, some gametophytes are euploid and diploid; for example,

AAAABBBBCCCCDDDD ![]() AABBCCDD

AABBCCDD

If a gametophyte of this constitution joins with an EEFFGGHH gametophyte, we will have instant fertile allopolyploidy.

16. In determining the evolutionary relationships among species, the first step is to look for species that are most similar to the ancestral form – that is, the one or ones that differ by the smallest number of chromosomal changes. Species C and species F differ from ancestral species A by only a single change in chromosome structure: species F by a loss of a centromere (a small deletion or centric fusion), and species C by a reciprocal translocation involving segments rs and on. Species B could, in turn, be derived from species C by a paracentric inversion:

bcd ![]() dcb

dcb

Note that it could also have been derived from A directly by both a translocation and an inversion, but the simplest hypothesis would be A ![]() C

C ![]() B

B ![]() . Species C also probably gave rise to species E; the only difference between them is a pericentric inversion of the segment cdef. Species D could be derived from species E by a reciprocal translocation of segments klm and dcg. Species F appears to have only the loss of the centromere to distinguish it from A, so it was apparently derived from the ancestral form separately. In summary, the hypothetical evolutionary sequence relating these species could be represented as is shown in the diagram that follows:

. Species C also probably gave rise to species E; the only difference between them is a pericentric inversion of the segment cdef. Species D could be derived from species E by a reciprocal translocation of segments klm and dcg. Species F appears to have only the loss of the centromere to distinguish it from A, so it was apparently derived from the ancestral form separately. In summary, the hypothetical evolutionary sequence relating these species could be represented as is shown in the diagram that follows:

17.

(a) The linear sequence of the mutations is a c d e b.

(b)

18.

Deletion heterozygote:

Duplication heterozygote:

Since the two situations appear essentially identical, the only way to tell them apart in an unknown bivalent would be to use some additional information. For example, if the chromosome has landmarks, like the polytene chromosome banding pattern in Drosophila, it should be possible to determine what landmarks are added or missing. Alternatively, if you know the length of a normal chromosome, it might be possible to tell whether the homologue is longer or shorter than normal, indicating a duplication or deletion, respectively.

19.

(b) 85E3—86A1.

20. The t gene is located somewhere in the set of bands that are lost in common with all four deletions, bands 31A4 through 31B1.

21. The order is F E A D C B.

CROSSWORD PUZZLE 16

Changes in Chromosome Number and Structure

Across

1. Describes the similar phenotypic expression found in individuals who have either an X chromosome or two X chromosomes

6. XO syndrome

7. A deactivated X chromosome as seen in female somatic cells

9. Condition in which patches of tissue differ in genetic makeup

13. Mosaic, for example, mice produced by the union of two different fertilized eggs

16. XXY syndrome

17. Term for having more than two sets of chromosomes

19. Term for an individual who has three copies of one type of chromosome

20. Term for having multiple copies of haploid sets of chromosomes (two or more haploid sets)

21. Polyploid having three sets of chromosomes

22. Sexual mosaic in which various tissues within an adult organism have different sexual karyo-types; often found in dipterans

Down

1. Describes a chromosome with two centromeres

2. Term for a change in chromosome number that involves a loss or gain of one or a few chromosomes

3. Another term for a haploid number of chromosomes

4. Describes a chromosome change in which a part of one chromosome is transferred to a non-homologous chromosome

5. Joining of two nonhomologous chromosomes; results in the loss of one of the centromeres

8. Change in the order of genes on a chromosome; due to two breaks and a turning around of the broken piece

10. Type of polyploidy in which the extra chromosome sets are derived from the same species

11. Mutual translocation between two non-homologous chromosomes

12. Inversion that does not involve the centromere

14. Chromosome without a centromere

15. Describes a polyploid whose extra sets of chromosomes were derived from different species

17. Inversion that involves the centromere

18. Loss of a DNA base pair, gene, or a piece of chromosome

19. Term for a polyploid having four sets of chromosomes