STUDY HINTS

In the Study Hints on DNA structure and replication in Chapter 3, we discussed the fact that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is a double-stranded molecule in which the individual strands are antiparallel to each other and have a 5′ end and a 3′ end. The process of protein synthesis involves using one of these DNA strands (the template strand) to produce a single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) molecule. This is accomplished by reading the DNA nucleotides from the 3′ toward the 5′ end, thus producing a 5′ to 3′ RNA. This process is termed transcription, which can be broken down into three stages: initiation, elongation, and termination.

Double-stranded DNA

5′ . . . TGCATGCATGGTTGCA . . . 3′ Coding or sense strand

3′ . . . ACGTACGTACCAACGT . . . 5′ Template or antisense strand

Transcription ![]() reads template strand from 3′ to 5′ to produce mRNA

reads template strand from 3′ to 5′ to produce mRNA

mRNA 5′ . . . UGCAUGCAUGGUUGCA . . . 3′

Translation ![]() reads mRNA from 5′ to 3′ to produce polypeptides

reads mRNA from 5′ to 3′ to produce polypeptides

N-terminal . . . Cys Met His Gly Cys . . . C-terminal

In the scientific literature, DNA sequences are generally reported by printing only the coding or sense strand (the one that has the same nucleotide sequence as the messenger RNA (mRNA), except having T instead of U; (B. Lewin, Genes VIII [Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2004]. The use of “coding” strand for the one that is not used in making the mRNA molecule seems confusing (we sometimes get confused, too!). Indeed, not all texts use these terms consistently, so you need to read carefully to be certain you know what process is being discussed.

Three major types of RNA are produced. Messenger RNA (mRNA) carries the genetic code for a polypeptide sequence. The mRNA nucleotides are read in triplets (codons). Transfer RNA (tRNA) carries amino acids to the ribosomes during polypeptide synthesis. Each tRNA has a three-base anticodon specific for one of the amino acids, and a 3′ end modified to bind to an amino acid. Several different ribosomal RNA (rRNA) types bind with proteins to produce the subunits of functional ribosomes.

The ribosome is composed of two major subunits (in prokaryotes, these are the 30S and 50S subunits). Within each subunit there are two regions, each of which will hold a codon of mRNA bound with the anticodon of an appropriate tRNA molecule and its amino acid. These ribosome-binding sites are the peptidyl (P) and the aminoacyl (A) binding sites.

Protein synthesis, or translation, can also be broken down into three stages: initiation, elongation, and termination. In the following outline, we summarize translation in prokaryotes.

I. Initiation

A. Small ribosomal subunit plus three initiation factors and a start tRNA (N-formylmethionine) are required to form a complex with the Shine-Dalgarno sequence 5′ to the start codon near the 5′ end of an mRNA.

B. The larger ribosomal subunit binds with the initiation complex and dislodges the initiation factors. The ribosomal complex now has the anticodon on f-Met tRNA complementing the start codon (usually AUG) on the mRNA within the P-binding site.

II. Elongation: This is a cyclical process in which new amino acids are added to a growing polypeptide chain.

As in the initiation of protein synthesis, elongation requires protein factors, which mediate the progressive addition of amino acids to the growing chain and help translocate the growing peptide from the A site to the P site. This translocation process requires energy and is equivalent to the ribosome running along the mRNA molecule codon-by-codon toward the 3′ end.

A. Once the f-Met tRNA is stable in the P site, elongation factors will place a tRNA carrying the complementary anticodon and its appropriate amino acid into the A-binding site and complex with the codon.

B. Peptidyl transferase, an enzyme present in the ribosome, catalyzes the formation of a peptide bond between the carboxyl group of the P site amino acid and the amino group of the A-site amino acid, transferring the P-site amino acid to the A site amino acid.

C. The now-deactivated tRNA in the P site is moved to an exit site, the E site. The remaining tRNA–mRNA complex moves to the open P site, and the process is repeated until a termination codon is encountered.

III. Termination

A. Three different codons can specify termination: UAA, UAG, and UGA.

B. When one of these appears in the A site, a termination protein causes the release of the polypeptide and breakdown of the ribosome complex.

C. The ribosomal units can then become part of another initiation complex.

The process of eukaryotic translation is similar to this but has the following important differences:

1. Ribosomal subunits are 40S and 60S in size.

2. Methionine in the initiation complex is not formylated, but a special initiation tRNA is used.

3. Proteins involved in initiation, elongation, and termination differ from those in prokaryotes. The process establishing ribosome assembly at the appropriate initiation codon is also different.

4. In prokaryotes, translation of the mRNA molecule can occur while its transcription is still in progress. In eukaryotes, however, mRNA is made in the nucleus and must be moved to the cytoplasm to bind with ribosomes.

Much of the early research on biochemical genetics involved the analysis of biochemical pathways that can be studied using auxotrophic (nutritionally deficient) mutants. These experiments helped establish the one gene/one enzyme hypothesis, later redefined to one gene/one polypeptide. After the equivalence of genes and polynucleotides had been confirmed, the stage was set for the breaking of the genetic code.

In the following problem set we have put together some simple and some more complex problems dealing with the analysis of biochemical pathways. Although some of these are rather complicated, the logic is straightforward. Do not get discouraged!

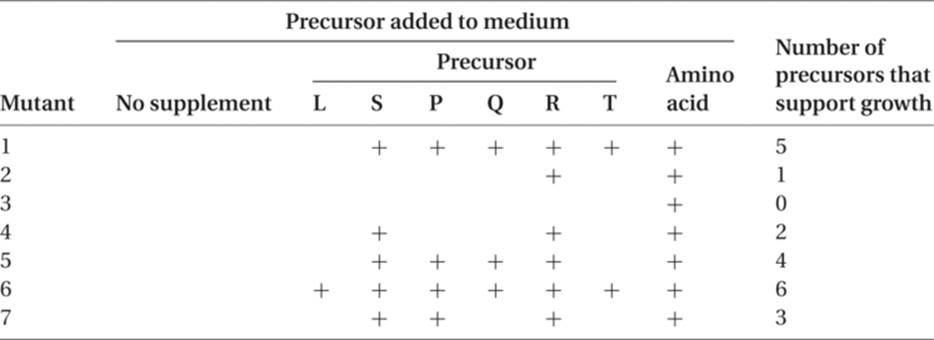

Consider the following problem. A number of different auxotrophic mutants are obtained in Escherichia coli, all of them requiring the addition of the same amino acid to minimal medium in order for these mutant strains to grow. When these mutant strains are grown on different minimal media, each supplemented with a different possible intermediate in the biosynthesis of the amino acid, the pattern shown in the following table is seen (the plus sign means restoration of normal growth, and no mark means no growth). Where do these intermediates fit into the pathway, and at what steps is each of the seven mutant strains defective?

The simplest assumptions are that L, S, P, Q, R, and T are all intermediates in the synthesis of the amino acid end product and that each mutant lacks one functional enzyme that catalyzes one of the steps in the amino acid synthesis. Analysis can be approached by way of the seven different mutant strains or by way of the intermediates (precursors). Before we attempt to solve this problem, however, we shall set up a simple hypothetical enzyme-controlled biosynthesis and study its implications.

Mutant strain (gene):

Intermediate: ![]() end product

end product

Precursor A is converted to B by action of an enzyme coded for by the wild-type (normal) allele of gene 1. A mutation at this locus that results in either the absence of the enzyme or a nonfunctional enzyme will not permit B to be produced. Genes, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 are all normal, and the enzymes they code are present. In the absence of B, however, no product is produced, and the organism will not grow in minimal medium. Mutant strain 1 will not grow if supplied with A, since its problem is in converting A to B. Strain 1 will be able to grow if given B, which it can convert to the end product. It follows that strain 1 will also grow if placed on media supplemented with C, D, E, or F, for it can convert any of these to the end product. If we look at a different strain, such as strain 4, we can see that it can make B, C, and D, but it has a block in converting D to E. Unless it is supplied with precursor E, it cannot make F and the end product. Strain 4 will also grow if supplied with precursor F.

If we look at mutant 6, it obviously cannot be benefited by addition of any of the precursors, since it can make all of them but cannot carry out the last step in the synthesis. We can conclude, therefore, that the smaller the number of intermediates that will permit growth, the closer that mutant gene is to the end of the synthetic pathway. The greater the number of intermediates that will permit growth, the further “upstream” that gene is functioning.

Returning to the original problem, R, the intermediate used by six of the mutants, is probably just before the amino acid, and the mutant that cannot grow if given R is probably blocked between R and the amino acid. This is mutant 3. Intermediate S can support growth of five mutants and is probably the immediate precursor of R. It cannot be used by mutant 3 or by mutant 2; this tells us that mutant 2 blocks between S and R. The next most frequently used intermediate is P, which is unable to support the growth of mutants 2, 3, and 4. We can conclude, therefore, that the sequence, to this point, is

![]()

Intermediate Q permits growth of three of the mutants. Adding mutant 7 to those that cannot grow, we conclude that mutant 7 blocks between Q and P. Using the same reasoning, T comes before Q, and the mutant that blocks the transition from T to Q is mutant 5. Finally, L can permit only one mutant (6) to grow, so this gene must block the synthesis of L from some unknown precursor earlier in the sequence, and mutant 1 must block between L and T. The pathway to the amino acid is, therefore

![]()

Several complications can confuse the picture. Sometimes two different genes seem to control the same reaction: For example,

![]()

There are several possible explanations for this. One is that it really is a single step, catalyzed by a single enzyme, but the enzyme is made up of two different polypeptides, one coded by gene 2 and the other coded by gene 3. Either mutation leads to a loss of enzyme activity. Alternatively, 2 and 3 may be alleles of the same gene. Another explanation is that there are really two steps, one controlled by gene 2, the other by gene 3:

![]()

The intermediate molecule may be transient or unknown. Another possible explanation is that the step from A to B is a single step, controlled by a single gene (for example, mutant 3), but mutant 2 determined the synthesis of a competitive inhibitor for the enzyme coded for by gene number 3. Even in the presence of the enzyme, the product of mutant 2 will block the action of the enzyme.

Working through the logical analysis of this type of problem will give you good experience in the interpretation of data, as well as allowing you to apply your knowledge of protein synthesis and activity.

IMPORTANT TERMS

Aminoacyl binding site (A-site)

Aminoacyl–tRNA synthetase

Anticodon

Auxotroph

Codon

Elongation factors

Heterogeneous nuclear RNA

Initiation factors

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

Nonsense codons

Peptide bond

Peptidyl site (P-site)

Peptidyl transferase

Polymerase

Polysome

Protein primary structure

Protein quaternary structure

Protein secondary structure

Protein tertiary structure

Prototroph

Releasing factors

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

Start codon (AUG)

Transcription

Transfer RNA (tRNA)

Translation

Wobble hypothesis

PROBLEM SET 17

Special note: Although these problems are not necessarily difficult, many of them, such as problems 9 through 12, may seem complex or time-consuming. Once you feel you understand how to approach one of these problems, you might go directly to the answers to check your reasoning, rather than spending an extended period working out the details yourself. A list of genetic codes is provided in Table R.3.

1. For the following mRNA molecule, 5′ AUGUUGCGCACGUAC 3′

(a) At which end will the ribosome and initiation factor bind?

(b) How many codons (and which codons) will initially be within the mRNA-ribosome complex?

(c) AUG codes for methionine and UAC for tyrosine. Which of these amino acids will be at the amino (N) terminal of the growing peptide chain?

(d) After elongation has started, if UUG occupies the peptidyl site of the ribosome, what codon will be in the aminoacyl site?

link to answer

2. Assume a DNA triplet pair:

3′ GTC 5′

5′ CAG 3′

where GTC is the template strand that transcribes mRNA.

(a) What is the amino acid coded for by the triplet?

(b) If a mutation occurs as a consequence of A’s being in its rare tautomeric state at the time of replication, what amino acid will be coded for?

link to answer

3. The amino acid sequence of a number of eukaryotic polypeptides is known. Does knowing the sequence of a polypeptide mean that all of the base sequence of its gene is also known? Please explain.

link to answer

4. Suppose you have a transcribed piece of mRNA. It contains 50 percent G, 10 percent U, 28 percent A, and 12 percent C.

(a) What would be the base ratios of the template strand of DNA from which this was transcribed?

(b) What would be the base ratios of the sense strand of the DNA double helix?

link to answer

5. Use the following DNA sequence to answer these questions.

(a) A base is added as the result of exposure to acridine dye. At which position (2 or 4) would it have the most damaging effect on the gene product? Please explain.

(b) What is the resulting change called?

(c) A base substitution at the 3′ end of the codon labeled 3 (1) will, (2) will not be more likely to produce an amino acid substitution than would a base substitution at the 5′ end of this same codon. Please choose the correct alternative and explain.

(d) The base guanine is added at position 1. What effect would it have on the gene product?

link to answer

6. If a synthetic mRNA contains 60 percent adenine (A) and 40 percent guanine (G), positioned at random along the polynucleotide, what amino acids are expected to be incorporated in the polypeptide, and in what proportions?

link to answer

7. A second synthetic mRNA contains 30 percent U and 70 percent G, positioned at random along the polynucleotide. What amino acids will be incorporated into the polypeptide, and in what proportions? Compare the number of amino acids coded for in this question and in question 6. What is the major reason for the difference?

link to answer

8. Assume that a short polypeptide sequence contains the following amino acids:

Met Trp Asp Cys Asn His Tyr

What can you say about the relative frequency of the four nucleotides in

(a) the mRNA molecule and

(b) in the template strand of the DNA that codes for this amino acid sequence?

link to answer

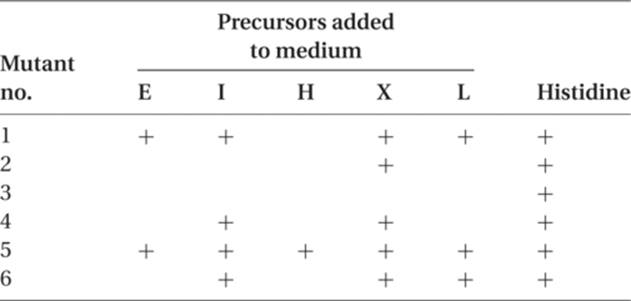

9. Assume in Neurospora that there are six different histidineless mutants, all nonallelic. When tested on a number of minimal media, each one supplemented with a single possible precursor to histidine, the growth pattern shown in the following table is seen, where plus (+) indicates growth. Determine the order in which the precursors occur in the synthesis of this amino acid. Indicate for each mutant the step in which it is involved.

link to answer

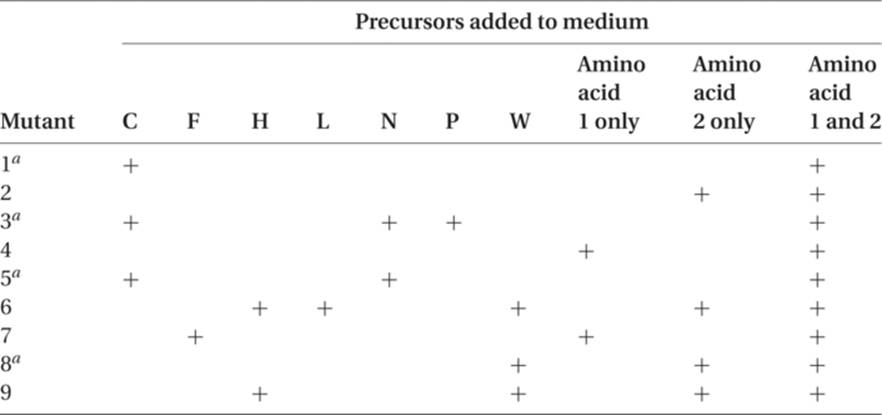

10. Eight independently derived, nonallelic mutants defective in vitamin B12 synthesis are recovered in Neurospora. Their growth on minimal media, each supplemented singly with one different possible precursor of vitamin B12, is indicated in the following table. From the data which is given in the table, indicate the order of the precursors in this synthesis, and show which steps are blocked by each mutant strain.

link to answer

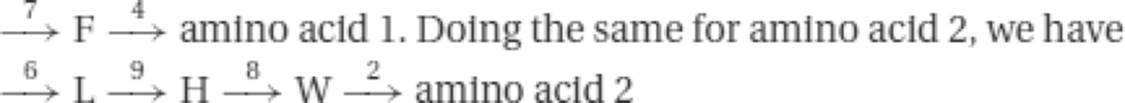

11. Assume that in Neurospora nine different nonallelic mutants have been isolated. Some can grow on minimal medium plus amino acid 1, some on minimal medium plus amino acid 2, and some require both amino acids in order to grow. Please describe the pathway(s) required to explain the data in the following table.

a These mutant strains accumulate large amounts of precursor H when placed in media that will support growth.

link to answer

12. In phage T4, a plus (+) frameshift mutant is suppressed by a second, minus (−) frameshift mutation at a different position in the cistron. The first 10 amino acids of the wild-type protein are

Met Phe Trp Ala Leu Glu Ser Met Asp Pro

and the first 10 amino acids of the protein coded for by the double frameshift mutant are

Met Phe Cys Gly Val Gly Glu His Asp Pro

What, and where, are the base changes associated with the plus and minus mutants, and what is the mRNA sequence for the first 10 amino acids for both the original wild-type proteins and the double-mutant proteins?

link to answer

13. Heating causes separation of double-stranded nucleic acid into its component strands, and cooling permits annealing (hydrogen bonding) of two strands with complementary sequences. Assume that the double-stranded DNA of a gene coding for a specific polypeptide in chickens is heated and separated.

(a) Some of this material is placed together with RNA from the nuclei of cells specialized to make a great deal of this polypeptide. The mixture is cooled, so that complementary strands can anneal. Electron microscope examination of the preparations shows single- and double-stranded nucleic acid. There are two kinds of double-stranded nucleic acid.

What do these two configurations represent?

(b) If the same DNA preparation has added to it RNA from the cytoplasm of these same specialized cells, and annealing of complementary strands occurs, one can see single- and double-stranded nucleic acid, and again, there are two different kinds of double-stranded nucleic acids:

What do these two configurations represent?

link to answer

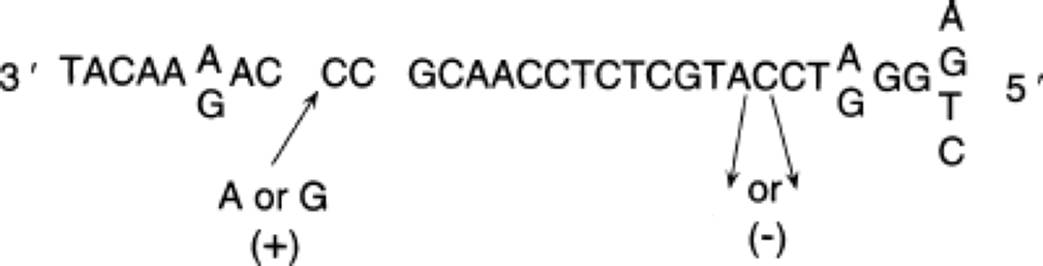

14. The following diagram describes the mRNA nucleotide sequence of part of the A protein gene and the beginning of the B protein gene of phage ϕX174. The B gene is completely enclosed within the A gene. Given the following amino acid changes, describe the base changes and the consequences for the other protein:

GCUAAAGAAUGGAACAACUCACUAAAAACCAAGCUGUCG . . .

![]()

(a) Asn at position 368 in the A protein is mutated to Tyr.

(b) Leu at position 370 in the A protein is mutated to Pro.

(c) Gln at position 8 in the B protein is mutated to Leu.

link to answer

ANSWERS TO PROBLEM SET 17

1.

(a) The 5′ end, AUG.

(b) Two codons: AUG and UUG.

(c) AUG methionine.

(d) CGC.

2.

(a) The complementary RNA codon will be 5′ CAG 3′, and the table of RNA codons (Table R.3) tells us that this codes for glutamine.

(b) In the changed state, A pairs like G, so it will hydrogen bond with C when the DNA is replicated. The tautomeric shift of a base in the sense strand will result in an altered codon in the template strand. The new DNA codon is 3′ GCC 5′, and the triplet in the mRNA is 5′ CGG 3′, which codes for arginine.

3. Two characteristics prevent us from inferring the DNA nucleotide sequence from a given amino acid sequence. The first is that the genetic code is degenerate in that several different codons can code for the same amino acid. Knowing the aimino acid therefore only means that you know the set of from one to six triplets at that point in the code that will produce that amino acid. Second, the genes in eukaryotes have many intervening sequences that are processed out before the mRNA leaves the nucleus.

4.

(a) 50 percent C, 10 percent A, 28 percent T, and 12 percent G.

(b) The same as the mRNA, except that there would be 10 percent thymine rather than uracil.

5.

(a) At position 2. The template strand is read in a 3′ to 5′ direction, so this is nearer the first part of the gene. The addition of a base here will cause a shift in the reading of the codons and result in a larger alteration in the coded sequence than a frameshift mutation farther along. We are sure you are aware, however, that since a gene is a long and complex sequence, the length we are working with on problems such as these may not, in practice, be different enough from the normal sequence to yield a major difference in protein function.

(b) Frameshift mutation.

(c) It will. DNA base substitutions at the 3′ end result in base substitutions at the 5′ end of the mRNA codon. The three possible DNA base substitutions result in A = Cys (the ACG DNA triplet yields the mRNA codon UGC); G = Arg (the mRNA codon is CGC); T = Ser (the mRNA codon is AGC). Since the DNA codon for glycine is CC (T, C, A, or G), the only tRNA molecule(s) that will form hydrogen bonds with the mRNA codons GG (A, G, U, or C) will be glycine-bearing tRNA molecules, and there will be no amino acid substitution, following a DNA base substitution at the 5′ end. This is described as the degeneracy of the genetic code.

(d) The frameshift mutant will have as its first three DNA codons AGC, AGA, and ATT, and the corresponding mRNA codons will be

5′ UCG UCU UAA 3′

(these code for Ser Ser terminator). The first amino acid in this sequence will remain unchanged. The second will be changed from phenylalanine to serine, and the polypeptide will be terminated here, since the third codon instructs the ribosome–mRNA complex to dissociate. This mutation is most likely to have a very damaging effect on the gene product. The closer it is to the 5′ end of the mRNA transcript, the greater the number of polypeptides lost.

6. The expected frequency of each possible triplet can be determined by listing them and multiplying the probability that each nucleotide will occur in each of the three positions. For example,

7.

In both this and the preceding question, there are four different combinations of the first two bases. In problem 6, with A and G, three of the four combinations (AA, AG, and GA) require either purine (A or G) in the third position to code for a particular amino acid. Since this synthetic mRNA contains only purines, only three amino acids are coded for by the six codons that start with AA, AG, and GA. The fourth combination, GG, will code for Gly, with any of the four bases in the third position. The number of amino acids coded for by A and G is four.

In problem 7, two of the four combinations (UU and UG) will each code for a different amino acid with a purine in the third position (note that this is not quite correct, since UGA codes for a nonsense stop triplet, but this has no bearing on the answer). In addition, two different amino acids are coded for if either of the two pyrimidines is in the third position. Since this synthetic mRNA is made up of a purine (G) and a pyrimidine (U), the beginning combinations UU and UG will ultimately code four different amino acids. Each of the two remaining combinations (GU and GG) at the beginning of a codon already specifies an amino acid, since the third position can be occupied by any of the four bases without changing the amino acid that is being coded. This synthetic mRNA thus codes for six amino acids.

8. From the reference table of mRNA codons (Table R.3) we can see that the seven amino acids are coded for by

![]()

(a) We can determine that of the 3·7 = 21 nucleotides, there are six A’s and five G’s with certainty. The number of U’s and C’s will vary, depending upon which of the codons for the last five amino acid are present. There are at least four U’s, and there may be as many as nine. There is at least one C, and there may be as many as six. The total number of U’s and C’s must add up to 21 total nucleotides −11 (that is, 6As + 5Gs) = 10 in the mRNA.

(b) Because the template strand of the DNA is the template for the mRNA sequence, it will have the complementary array of nucleotides. It will then certainly contain six T’s and five C’s. There will be at least one G, and there may be as many as six. The total number of A’s and G’s must add up to 10.

9. There is a simple logic to working this kind of problem, and there is a pattern, when the data are presented in the tabular form that we have used. Since none of the mutants is allelic, they are probably involved in different steps of histidine synthesis. We can assume that each mutant blocks only one step in the synthesis, probably by the loss of a functional enzyme. There are two different (but related) ways of solving this problem. Select the approach that is clearer or more aesthetically pleasing to you.

I. Mutant method: This method concentrates on the mutants, which differ in the number of precursors they can use to make histidine.

A. The mutant (3) that cannot use any precursor blocks the last step in histidine synthesis. (This and similar remarks are valid only for the steps between the precursors that are given in the question.)

This gives us ![]() .

.

B. The mutant (2) that can grow on only one precursor (X) blocks the next to last step in His synthesis, and the precursor that permits growth is the one whose synthesis is blocked by a mutant.

We now have ![]() .

.

C. The mutant that blocks one step earlier will be able to grow if supplied with X or with a second additional precursor. The mutant (4) can grow with X and with I. The path is now

![]()

D. There should be a mutant that can grow on either X, I, or a third precursor. Mutant 6 is the one, and the new precursor is L:

![]()

E. The next precursor (working backward) should be indicated by a mutant that can grow on X, I, L, and a fourth precursor. This mutant is mutant 1, and the new precursor is E. This gives us

![]()

F. The remaining mutant (5) can grow on all of the four precursors just listed but can also grow when supplemented with H. This permits us to complete the synthetic pathway:

![]()

(Please excuse the “subliminal” reinforcement of the structure of DNA.) Each mutant blocks only one step in the synthesis, presumably by coding for an inactive or missing enzyme. Each mutant will grow on minimal medium supplemented with any one of the precursors downstream (after the affected step), but it cannot grow on minimal medium supplemented with any of the precursors upstream (before the affected step).

II. Precursor method: The second method focuses on the precursors rather than on the mutants. A glance at the table in question 9 shows that each precursor is utilized by a different number of (upstream) mutants.

A. X shows the maximum number, five (mutants 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6). This should place X immediately before histidine (again, this placement is valid only for the precursors being tested) and should assign to mutant 3 the control of the ![]() .

.

B. The precursor that is used by 5 − 1 = 4 mutants is I, and the two mutants that will not grow on I are mutant 3 (already assigned a step) and mutant 2. We now have ![]() .

.

C. The next (upstream) precursor will have three pluses in the table, and this is L, with mutant 4 appearing as the third mutant that will not grow unless supplemented by L (in addition to mutants 2 and 3). This gives us ![]() .

.

D. The precursor that is used by two different mutants is E, and this adds mutant 6. So the mutants that are downstream of E are 6, 4, 2, and 3 in that order: ![]() .

.

E. The precursor that is used by only one mutant is H, and we can add mutant 1 to the pathway just before E, and mutant 5 to the pathway before H: ![]() . We now have a complete synthesis coded for by genes 5, 1, 6, 4, 2, 3, in that order.

. We now have a complete synthesis coded for by genes 5, 1, 6, 4, 2, 3, in that order.

10. Following the logic of problem 9, mutant 6 blocks just before vitamin B12. Q is the last precursor, requiring the wild-type allele of mutant 2 to catalyze its synthesis from C, whose presence depends on the wild-type allele of mutant 5. Precursor M is converted to C by gene 5, whereas M appears to depend on two genes, 3 and 8, whose products are involved in converting B to M. The normal allele of gene 7 is involved in the H–to–B reaction, whereas the wild allele of gene 1 is responsible for the Y–to–H step. The normal allele of gene 4 acts on some unknown precursor, resulting in the production of Y. The steps are indicated as follows:

![]()

With the mutants available, there is no evidence that P is even a precursor, since no mutants grow if given P. A more challenging problem is the B–to–M step, which is blocked by the mutant allele of either gene 3 or gene 8. If genes 3 and 8 were duplicate genes that had become separated, both mutant alleles would be necessary to block M synthesis. The data indicate that this is not the case. One explanation is that there are two steps, with a transient intermediate between B and M, so that we have, for example, ![]() . A second possibility is that B to M is a single step, catalyzed by an enzyme made up of two different polypeptides, one coded for by gene 3, the other by gene 8. Such enzymes are well known. The enzyme can be inactivated by mutations in either of the two genes. The third possibility is that only one gene, let us say gene 3, is responsible for the enzyme that converts B to M, but the mutant allele of gene 8 codes for a competitive inhibitor that blocks the B–to–M reaction.

. A second possibility is that B to M is a single step, catalyzed by an enzyme made up of two different polypeptides, one coded for by gene 3, the other by gene 8. Such enzymes are well known. The enzyme can be inactivated by mutations in either of the two genes. The third possibility is that only one gene, let us say gene 3, is responsible for the enzyme that converts B to M, but the mutant allele of gene 8 codes for a competitive inhibitor that blocks the B–to–M reaction.

11. Results like this puzzled (although not for long) the early workers in the biochemical genetics of Neurospora. Prior to this, all auxotrophic mutants had been found to have only one requirement, such as an amino acid, a purine or pyrimidine, or a vitamin. Here, three nonallelic mutants (1, 3, and 5) had a double requirement for both amino acids. Mutants 4 and 7 were deficient in amino acid 1 only, whereas mutants 2, 6, 8, and 9 were deficient in amino acid 2 only. The objective is to diagram the biochemical pathways to amino acids 1 and 2, indicating which mutant gene affects which step.

It is probably wise to start out with the known and familiar – that is, those mutant strains that require only one amino acid (1 or 2). Mutant 4 will grow only with amino acid 1 added, whereas mutation 7 will grow on amino acid 1 or on precursor F. So we can make a minor pathway thus:

The remaining mutants, 1, 3, and 5, require both amino acids, and one explanation is that they are involved in a sequence that is common to both amino acids. Examination of the data for these mutants gives us the pathway ![]() C, and we can try to devise schemes in which C is common to both amino acids. One such scheme is

C, and we can try to devise schemes in which C is common to both amino acids. One such scheme is

This pathway is consistent with the growth results in the table in question 11, but it does not help to explain the unusually large accumulation of precursor H in mutant strains 1, 3, 5, and 8. Sometimes, in this type of research, a blocked step can cause the accumulation of the intermediate on the “good” side of the block; for example, in

![]()

where the B-to-C step is blocked, B may continue to be synthesized and may accumulate in large amounts. In some cases the high level of B may also cause higher levels of earlier precursors such as A or of the other molecules for which B may be a precursor. There are a number of inherited blocks in human biosynthetic pathways in which intermediates whose normal pathway is blocked pile up in the tissues and/or urine. This may result in excessive production of related molecules, causing conditions such as phenylketonuria and alkaptonuria. In this case the H molecule’s continuing modification appears to be blocked. A pathway that is compatible with the data is

With mutants 1, 3, and 5, there is no C, and since H normally combines with some of the C molecules (under control of the gene affected in strain 8) to form W, H piles up in the organism. If the condensation of C and H is blocked by mutant gene 8, H also piles up, since, again, it is not being incorporated into W.

Can you come up with a different scheme that will be compatible with these data?

12. This is really not a very difficult problem, but it can be messy, and good organization will facilitate its solution. Here is one way to go about it:

(a) List the amino acids in order, together with all possible RNA codons, for both proteins. Arrange them so that the frameshift consequences are easily seen, for example:

(b) Clearly, one frameshift mutation changes the third through the eighth codons; the first, second, ninth, and tenth codons are assumed to be the same in both mRNAs (and DNAs).

(c) Amino acid 3, Trp to Cys. For this change, the addition of U or C between the second and third bases of the Trp codon is needed. There is no deletion of a base that can result in the Trp-to-Cys mutation.

(d) Amino acid 4, Ala to Gly. The plus (+) mutation now causes the third base (G) of the wild-type Trp codon to act as the first base of the codon for the fourth amino acid in the mutant polypeptide (as shown by the lines we have drawn in the figure). Since the first two bases of the wild-type Ala codon must be GC, this makes the fourth amino acid of the mutated protein coded for by GGC (Gly).

(e) Amino acid 5, Leu to Val. The third base in the Leu codon can be any one of the four, but since Val is coded for by GU (UCAG) and the first base of the Val triplet is the last base of the Ala triplet, the original Ala in the wild-type protein was coded for by GCG. Furthermore, since the second base in the Val codon must be U, this permits us to rule out CU (UCAG) as the codon for Leu in the wild-type.

We might pause here to make an observation that will facilitate answering this question. Until we arrive at the end of the mutated sequence and are once more on the original reading frame, the codon for any mutated amino acid will be derived from the last base of the codon for the wild-type amino acid just before it, combined with the first two bases of the wild-type amino acid in the same position. For example, the mutated Val (5) is coded for by G (the last base of wild-type amino acid 4) plus UU (the first and second bases of the wild-type amino acid 5).

(f) Amino acid 6, Glu to Gly. Since Gly is coded for by GG (UCAG), it follows that the last base of the original Leu (5) was G, and since Glu is coded for by GA (AG), the new Gly must be coded for by GGA.

(g) Amino acid 7, Ser to Glu. Since Glu is coded for by GA (AG), we concluded that the last base of the wild-type Glu in position 6 was G. It is also obvious that the wild-type Ser is not coded for by UC (UCAG) but by AG (UC), and since the mutated Glu derives its last two bases from the first two bases of Ser, the codon for Glu is, unambiguously, GAG.

(h) Amino acid 8, Met to His. The last base of the Ser codon can be U or C, but since His, which gets its first base from the last base of the wild-type Ser, is coded for by CA (UC), the original Ser was coded for by AGC. The His codon must be CAU, deriving A and U from the AU of Met.

(i) Amino acid 9 and amino acid 10, Asp Pro . . . on both proteins. We are now obviously back to the original reading frame, which means that there is a minus (−) mutant lurking in the vicinity, compensating for the plus (+) mutation in the third codon. In the absence of the minus (−) mutation, the next four bases of the plus (+) mutant are ![]() .

.

For Asp, we need ![]() . We can obtain this triplet by losing either of the two G’s as a minus (−) mutation. This gets us back on the original reading frame, and amino acids Asp Pro and so on.

. We can obtain this triplet by losing either of the two G’s as a minus (−) mutation. This gets us back on the original reading frame, and amino acids Asp Pro and so on.

It may now be obvious to you that the analysis of amino acid changes in frameshift mutations permits us to remove the veil of degenerate ambiguity that clouds the codons. In the example given earlier, the possible codons for amino acid 4 through amino acid 7 of the wild-type included as few as two and as many as six possible triplets for these four different amino acids. It also gives us the exact codons for amino acid 4 through amino acid 8 of the mutant protein. Studies of this type were one of the several different experimental approaches to the determination and verification of the genetic code.

To summarize, the first 10 amino acid and codon sequences for the wild and mutated polypeptides are:

In answer to the question, the base changes associated with the plus and minus mutations occurred in the DNA, of course. The entire DNA (template-strand) sequence (which, remember, is complementary to the mRNA sequence) is as follows, with the plus (+) and minus (−) mutants indicated:

13.

(a) Molecule 1 results from annealing of the template strand of DNA and its RNA transcript. The third strand, the coding DNA strand, can pair with the template strand in regions where there is no transcription, and hence no pairing of DNA and RNA strands. Molecule 2 results from reannealing of the two DNA strands, the complementary template and coding strands of the gene.

(b) Molecule 1 results from the hydrogen bonding of the template and coding strands of the gene, whereas molecule 2 results from hybridization of the template strand with the RNA transcript from the cytoplasm. The primary RNA transcript has been tailored in the nucleus, so that three internal segments have been excised and the four separate pieces rejoined to form the end product, mRNA. The loops occur where the template strand of DNA has no complementary RNA to pair with. These sections of the DNA are called introns. The coding strand of the gene is annealed with the template strand outside the limits of the gene and also at the introns.

14.

(a) Asn (AAC) can code for Tyr (UAC) by a transversion of the first base. This will change the middle base in the third amino acid (Gln) of the B protein to U, which will make that codon CUA, which codes for Leu. So this mutation results in an amino acid change in both proteins.

(b) Leu (CUA) can code for Pro (CCA) by a transition of the middle base. This will change the last base in the fifth amino acid (Thr) of the B protein to C but will not change the amino acid, since ACU and ACC both code for Thr.

(c) Gln (CAA) can code for Leu (CUA) by a transversion of the middle base. This will change the first base in the codon for Lys (amino acid 373) of the A protein to U, making that codon UAG, which is a terminator or nonsense codon. As a result, only the first 372 amino acids of the A protein will be translated, and the last 141 amino acids will be missing. This probably will have a serious effect on the protein’s functioning and on the ability of the virus to reproduce, since the A protein is involved in the replication of the replicative (double-stranded) form of the viral DNA.

CROSSWORD PUZZLE 17

Protein Synthesis and the Genetic Code

Across

1. Sequence of three nucleic acid bases found on tRNA

3. ___ methionine that is the start amino acid for prokaryotes

5. ___ factor, a protein that brings about the cleavage of the protein from the ribosome

10. Small RNA sequences with associated proteins that are involved in intron removal

13. Complex enzyme that can read DNA sequences and build complementary RNA sequences

14. RNA polymerase that is required in eukaryotes for tRNA transcription

15. Carries the anticodon

17. Protein needed in some prokaryotes for transcription termination

18. Three bases in RNA that code for an amino acid

19. Bond between two amino acids

23. RNA that carries the DNA code for an amino acid sequence

25. Aminoacyl-___enzymes that are specific for activation or charging tRNA with an amino acid

27. Term for the movement of the ribosome along the mRNA

Down

2. Carries the anticodon

4. Start amino acid in translation of all known proteins

6. 5′−5′ 7-methyl guanosine attached to eukaryote mRNA

7. Several ribosomes attached to one mRNA

8. 3′ Sequence placed on mRNA of eukaryotes before they leave the nucleus

9. Term for making an RNA sequence from a DNA

11. Three-base codon that does not have a complementary anticodon

12. Refers to the code in which more than one codon can code for one amino acid

16. Removal of introns from RNAs

19. Sequence on DNA that allows initiation of transcription

20. tRNA binding site on the ribosome, where peptide bonds are formed

21. Sequence of amino acids

22. Idea that the 5′ end of the anticodon can form hydrogen bonds with more that one 3′ codon base

24. Structure of polypeptides such as the alpha helix and the beta pleated sheet

26. Start codon