STUDY HINTS

The rules of Mendelian inheritance are largely based upon the probabilities of inheriting a given allele or combination of alleles from a specified genotype. With the exception of sex-linked traits, each individual carries at most two alleles of each gene, and the number of possible combinations is limited. Expectations can be calculated easily, since the probability of getting a certain allele from a known heterozygous diploid is p = q = .5.

In a population the focus changes from the genome to the gene pool and to estimates of allele frequency, yet the rules of probability still apply. Allele frequencies p and q are determined by pooling all of the genes carried by all of the individuals in the population. Working problems that require estimating allele and genotype frequencies from the Hardy–Weinberg relationship are fairly straightforward if you keep in mind that you are dealing with probabilities and if you are consistent with your use of symbols.

For example, if we let the frequency of the A allele be p and the frequency of the a allele be q in a population in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, p + q = 1, as long as A and a are the only alleles at that locus segregating in the population. In other words, the probability of picking an A allele at random plus the probability of picking an a allele at random account for all possible events. The genotypes that can be produced and their probabilities are shown in the following table. Remember the rule that the probability of two independent events occurring together is the product of their individual probabilities.

The sum of the probabilities of each genotype also accounts for all possible genotypic events and therefore equals 1.

Thus, if you can determine the frequency of homozygous recessive (aa) individuals in a population, for example, you have q2. Its square root (q) can then be used to determine the frequency of the A allele, since p = 1 − q. Given pand q, you can then estimate the frequencies of each genotype.

The Hardy–Weinberg law describes the fact that allele frequencies and genotype frequencies will not change if certain assumptions are made about the population. These assumptions include an infinite population size, random mating, and the absence of mutation, migration, and selection. In the following outline we have summarized some of the effects on allele frequencies and genotypes that one might expect if any of these assumptions were to break down.

Genetic consequences when Hardy–Weinberg assumptions break down:

I. Small population size: If the population size is small, random sampling errors (chance) can cause unpredictable changes in allele frequencies that are independent of any other factors acting on the population. Over time, this sampling error (or genetic drift) can lead to fixation (homozygosity) of one allele or the other.

II. Deviations from random mating: Deviations from random mating mean that certain matings occur at frequencies different from those predicted purely on the basis of genotype frequencies in a population. There are several types of deviation from random mating, and these can have different effects upon the population.

A. Assortative mating: Mating between phenotypically or genotypically similar individuals increases homozygosity for the loci involved in mate choice (and those loci in linkage disequilibrium with them) without altering allele frequencies.

B. Disassortative mating: Mating between dissimilar individuals increases heterozygosity without altering allele frequencies.

C. Rare-male mating advantage: Density-dependent mating generally tends to increase the frequency of the rare allele and thus increase heterozygosity.

D. Inbreeding: Mating between close relatives increases homozygosity for the whole genome without affecting allele frequencies.

III. Mutation: Mutation changes allele frequencies at a rate that depends upon many factors, such as repair ability, mutator factors, chemical and physical mutagens, and the frequency of the alleles themselves. The role of the allele frequency can be illustrated by considering the mutational equilibrium:

where a and a′ are two allelic forms, and u and v are the forward- and back-mutation rates. Changes from one allele to the other in a population will be a function of the frequency of each type of allele and the magnitude of u and v. In general, the rate of forward mutation is significantly greater than the rate of back-mutation, since there are many ways to create an error in coding, but fewer ways to correct it. The rate of mutation from a to a′ is u times p, where p is the frequency of the a allele. The reverse mutation rate is v times q. Thus the change in gene frequency (Δq) is up − vq. If mutation rates remain constant, a stable equilibrium will be reached when

and the equilibrium frequency of q (symbolized ![]() ) is

) is

IV. Migration: Migration, or gene flow, alters allele frequencies in a way that depends upon the difference between the allele frequency in the migrant (qm) and the recipient (qr) populations and upon the proportion of migrants (m). The new allele frequency in the recipient population is

![]()

The change in allele frequency, Δq, is therefore

Allele frequency is stable (Δq = 0) when qm = qr

V. Selection: Selection changes allele frequencies and thus genotype frequencies, as a function of the relative fitness of a given genotype. Types of selection are discussed in the Study Hints section in Chapter 22.

IMPORTANT TERMS

Assortative mating

Balanced polymorphism

Deme

Disassortative mating

Founder principle

Gene frequency

Gene pool

Genetic drift

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium

Heterosis

Inbreeding

Inbreeding depression

Linkage disequilibrium

Mutation equilibrium

Panmixia

Population

Selection

Unstable equilibrium

PROBLEM SET 21

1. Suppose that an autosomal trait, hairy earlobes, is found in 3.24 percent of a certain population. Pedigree analyses of this population confirm that all matings between individuals with hairy earlobes produce only hairy-lobed offspring. If the population is in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, what percentage of the population will be heterozygous carriers of this trait?

link to answer

2. If albinism occurs in only 1 individual in each 10,000 in the population, how many matings at random in this population will be between heterozygous carriers? (Note that “mating at random” refers only to the fact that mates are not chosen on the basis of the trait in question.)

link to answer

3. A class of 75 students was tested for their ability to taste the chemical phenylthiocarbamide (PTC). A total of 48 were found to be tasters, expressing the dominant trait. What is the frequency of the recessive (t) allele in this sample? How frequently would one expect a homozygous nontaster (tt) to date a homozygous taster (TT), if dating were at random with respect to this phenotype?

link to answer

4. Phenylketonuria is a metabolic disorder that can cause irreversible brain damage in early life if not treated by controlling the dietary intake of phenylalanine. In a certain hypothetical population, phenylketonuria occurs in 1 in each 40,000 individuals. First calculate the frequency of homozygotes and heterozygotes. Then determine what proportion of all possible matings will have the potential of giving rise to at least one affected individual in the family. Note that the question asks about matings, not the frequency of the resulting affected offspring.

link to answer

5. In a certain strain of Drosophila melanogaster, the dominant mutation “Lobe eye” (L) has 90 percent penetrance in both homozygotes (LL) and heterozygotes (Ll). In a population containing both Lobe eye and wild-type flies, 5,760 of 10,000 are found to express the Lobe phenotype. What proportion of the population is expected to be heterozygous for this dominant condition?

link to answer

6. Suppose that a population of diploid cross-fertilizing (that is, outbreeding) individuals in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium is suddenly forced into an exclusively self-fertilizing mode of reproduction. Considering a single locus with two alleles in this population, what will happen to the distribution of the

(a) genotype,

link to answer

(b) phenotype,

link to answer

(c) gene frequencies?

link to answer

link to answer

7. If the gene frequency of the M blood allele is .6 and the gene frequency of the N allele is .4, what is the probability that a man accused of being the father of a child with blood type N will be cleared by MN blood-type testing? Assume that the man is picked at random from a population and is not the actual father of the child.

link to answer

8. If the frequency of female Drosophila exhibiting the recessive sex-linked trait cross-veinless (cv) in an experimental population is .36, what is the expected frequency of male Drosophila exhibiting this trait?

link to answer

9. Dyslexia (congenital word blindness) is an autosomal dominant trait in humans. If the frequency of this trait is about 19 affected people in each 100 in a certain population, how frequently would one expect matings to occur between a heterozygote and a homozygous affected individual?

link to answer

10. In a certain population of self-fertilizing Hydra, 84 percent are heterozygous for a tentacle-number mutation. After three generations of total inbreeding, what will be the percentage of heterozygosity in this population?

link to answer

11. A hypothetical population of grasshoppers is in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for two unlinked mutations. One is a recessive mutation causing shortened legs. The common long-legged phenotype is found in 99 percent of the individuals. The second mutation affects electrophoretic mobility of the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) enzyme. The slow-mobility allele is homozygous in only 16 percent of the grasshoppers. What proportion of the population is expected both to have the short-legged phenotype and to be heterozygous for mobility alleles of Ldh?

link to answer

12. Please consider the following pedigree for a relatively common inherited condition in which the frequency of the dominant allele is .23 in the population at large. First determine the mode of inheritance. Then calculate the probability that the child IV-2 inherits the condition. If IV-2 is unaffected and marries at random with respect to this condition, what is the probability that the couple’s first child will show the trait?

link to answer

13. Assume that there are two populations of house mice living in adjacent farms. They differ in the allelic frequency of the recessive albino mutation. In population 1 the frequency is .3 and in population 2 it is .6. Assume further that the harvest is better in farm 1, so that mice from population 2 migrate in. The proportion of immigrants is .2. What is the change in allelic frequency for the albino gene in the new population of farm 1?

link to answer

ANSWERS TO PROBLEM SET 21

1. Since all matings between affected individuals produce only affected offspring, the trait must be a recessive. Since the population is in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, one simply uses the observed frequency of affected individuals (q2) to calculate q, p, and 2pq. Since q2 = .0324, q = .18. Since p = 1 − q, p must be .82. Then, 2pq = 2(.18)(.82) = .2952.

2. Since q2 = .0001, q = .01. Thus p = .99, and the frequency of heterozygotes (2pq) = .0198. A mating between two heterozygotes is composed of two independent events (the likelihood that the father is a heterozygote and the likelihood that the mother is a heterozygote). Such a mating is then a function of the product of the two independent probabilities (.0198 · .0198). The expected frequency of heterozygote mating is therefore .00039, or .039 percent.

3. First one needs to calculate the frequency of homozygous recessive nontasters. There are 75 − 48 = 27 nontasters, who make up 27![]() 75, or 36 percent, of the population. If nontasting (tt) is q2, then q2 = .36, so q = .6 and p = .4. The frequency of homozygous tasters (TT) = p2 = .16. A dating pair could be tt

75, or 36 percent, of the population. If nontasting (tt) is q2, then q2 = .36, so q = .6 and p = .4. The frequency of homozygous tasters (TT) = p2 = .16. A dating pair could be tt ![]() × TT

× TT ![]() or TT

or TT ![]() × tt

× tt ![]() . Thus the probability of such an occurrence is 2(.36)(.16) = .1152.

. Thus the probability of such an occurrence is 2(.36)(.16) = .1152.

4. Since q2 = 1![]() 40,000, q = 1

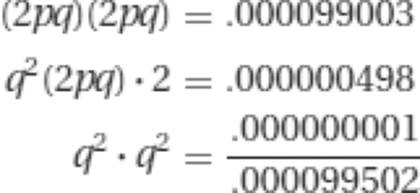

40,000, q = 1![]() 200, or .005. Thus p = 1 − q = .995. The frequency of homozygous normal individuals is p2 = (.995)2 = .990025. The frequency of heterozygous individuals is 2pq. This is 2(.995)(.005) = .00995. We already have q2 = .000025. Only the four matings that involve individuals carrying at least one recessive (a) allele could produce a homozygous aa offspring. The total proportion of potentially affected families is simply the sum of these four probabilities.

200, or .005. Thus p = 1 − q = .995. The frequency of homozygous normal individuals is p2 = (.995)2 = .990025. The frequency of heterozygous individuals is 2pq. This is 2(.995)(.005) = .00995. We already have q2 = .000025. Only the four matings that involve individuals carrying at least one recessive (a) allele could produce a homozygous aa offspring. The total proportion of potentially affected families is simply the sum of these four probabilities.

|

Mothera |

Fathers |

||

|

AA |

Aa |

aa |

|

|

AA |

X |

X |

X |

|

Aa |

X |

(2pq)(2pq) |

q2(2pq) |

|

aa |

X |

q2(2pq) |

q2(q2) |

a Where A = normal, and a is phenylketonuria.

5. Let us define p and q so that p is the frequency of the dominant Lobe allele and q is the frequency of the wild-type allele. The individuals carrying the Lobe mutation will therefore be represented by p2 + 2pq, since they will include both homozygous dominant and heterozygous individuals. One must determine the proportion of genetically homozygous wild-type individuals (q2) in order to calculate p and q. To calculate p2 + 2pq from the data in the problem, one must first take into account that some flies in this class will not have expressed this trait, since penetrance in our strain is only 90 percent. That is, p2 + 2pq times the penetrance is the number of carriers that will show the trait. Thus, to determine the actual size of this class,

Thus q2 = 1 − (p2 + 2pq) = .36, and q = .6. Since p + q = 1, p = .4.

The proportion expected to be heterozygous for the condition is 2pq = 2(.6)(.4) = .48. Remember, however, that this does not mean that all individuals within this 48 percent of the population will express the trait. The value 2pq only gives the genotypic frequency. Phenotypic frequency must again take penetrance into account. Since this problem asked for genotypic frequency, the correct answer is 48 percent. If we had asked for phenotypic frequency, however, the answer would have been (.48)(.9).

6.

(a) Inbreeding associated with self-fertilization increases the frequency of homozygotes and decreases heterozygosity. Half of the progeny of each heterozygote in each generation of such extreme inbreeding are homozygous, and there is no way of regenerating new heterozygotes without some form of outcrossing (in the absence of some other factor such as mutation).

(b) The two homozygous phenotypes would eventually be the only phenotypes.

(c) Inbreeding changes only phenotype and genotype frequencies. It does not alter allele frequencies.

7. Let p = the frequency of the M allele = .6, and let q = the frequency of the N allele = .4. The man would be unambiguously cleared only if his MN blood type is M (that is, if he is an MM homozygote), because only then could he not contribute an N allele to the genotype of the child. Thus the frequency of MM genotypes, p2 = (.6)2 = .36, gives the probability that this test alone will exonerate him.

8. If the frequency of Drosophila females exhibiting the sex-linked trait is .36, the allele frequency (q) must be .6 (i.e., ![]() ), since females have two X chromosomes. The males, on the other hand, have only one X chromosome. The probability that they carry the recessive mutation is therefore the same as the frequency of mutant X chromosomes in the population (.6).

), since females have two X chromosomes. The males, on the other hand, have only one X chromosome. The probability that they carry the recessive mutation is therefore the same as the frequency of mutant X chromosomes in the population (.6).

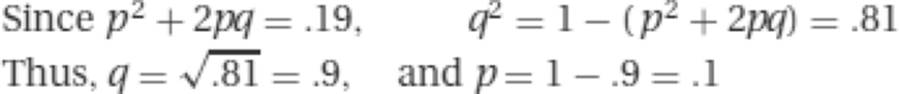

9. The frequency of those showing the dominant trait (.19) includes both homozygous dominant individuals and those heterozygous for the dominant. In order to determine allele frequencies, therefore, we must determine the proportion of the population that is homozygous for the recessive allele.

The frequency of heterozygotes is 2pq = 2(.9)(.1) = .18. The frequency of homozygous affected individuals is

![]()

(Note that the sum of these two values accounts for the observed frequency of dominant-phenotype individuals in the population.) Since a mating between a heterozygote and a homozygous affected individual could occur in either of two ways (homozygous man with heterozygous woman, and vice versa), the overall probability of the mating is

![]()

10. The proportion of heterozygotes is halved each generation, since a heterozygote that self-fertilizes produces 1![]() 4 AA and 1

4 AA and 1![]() 4 aa individuals, leaving only half as many heterozygotes as the population began with. In the Hydrapopulation, there will be 42 percent heterozygotes after one generation of self-fertilization, 21 percent after two generations, and 10.5 percent after three.

4 aa individuals, leaving only half as many heterozygotes as the population began with. In the Hydrapopulation, there will be 42 percent heterozygotes after one generation of self-fertilization, 21 percent after two generations, and 10.5 percent after three.

11. The frequency of the recessive allele for short legs is the square root of the frequency of the homozygotes (1 in each 100 in the population). Thus q2 = .01, and q = .1, so p = 1 − q = .9. For the Ldh slow-migrating allele, since 16 percent are homozygous the frequency of LdhS = .4 and the frequency of the fast allele, LdhF, is .6.

The probability of obtaining a short-legged individual that is heterozygous for the Ldh locus is the product of the separate probabilities for each event. The probability for short legs is .01 and for being LdhSLdhH = 2(.4)(.6) = .48. The overall proportion of the population fulfilling both genetic requirements is (.01)(.48) = .0048.

12. The trait is a dominant, because each affected individual has at least one affected parent, and normal offspring do not transmit the trait to their children. The trait is also autosomal, because there is an example of father-to-son transmission (male I-1 to son II-4). The probability that female III-4 will transmit the dominant allele to the child is therefore 1![]() 2.

2.

If child IV-2 is unaffected, the transmission of the trait to the next generation would depend upon the genotype of the other parent, with probabilities differing if the person is homozygous or is heterozygous. Since the frequency of the mutant allele is .23, the probability that the parent is homozygous is (.23)2 = .0529. The probability of being heterozygous is 2(.23)(.77) = .3542. The likelihood of transmission from a homozygote to a child is 1; the likelihood of transmission from a heterozygote to a child is 1![]() 2. Thus the total probability that a child of IV-2 will inherit the trait is (.0529)(1) + (.3542)(.5) = .23.

2. Thus the total probability that a child of IV-2 will inherit the trait is (.0529)(1) + (.3542)(.5) = .23.

13. The change in allele frequency Δq = m(qm − qr), where m is the proportion of migrants (.2 in this case) and qm and qr are the allele frequencies in the migrant and recipient populations, respectively. Thus,

In other words, since the frequency of the albino allele is higher in population 2, the migrants will carry a higher proportion of the albino alleles and will increase the frequency in the recipient population by .06 (that is, from .30 to .36).

CROSSWORD PUZZLE 21

Basic Population Genetics

Across

1. Changes in gene frequency caused by limited population size

8. Total genetic makeup of a population

9. Term for the heterozygous genotype’s being more fit than either homozygous genotype

12. Local inbreeding population that has an equal chance of mating with other members of the opposite sex in the same local population

13. Equilibrium that, if disturbed and then allowed to return to equilibrium, will not return to the original equilibrium point

15. Only method, other than selection, in which directional change in gene frequency occurs

18. __ mutation: condition whereby a mutant genotype changes to wild-type

19. Principle that refers to a form of genetic drift in which only a small sample of a population’s gene pool is used in establishing a new population

20. Group of individuals of the same species in a defined area

Down

2. Matings between relatives in a population

3. Detectable and heritable change in genetic material, unrelated to recombination or segregation

4. Term for selection maintaining large amounts of genetic variation within populations

5. Elimination of genotypes due to competition or preference for another genotype

6. Proportion of one allele relative to other alleles of a specific gene in a population

7. __ mating: selective mating of unlike phenotypes

10. Refers to chance deviation from expected ratios due to small sample size

11. Occurrence of alleles from different genes together more often than predicted by their individual frequencies

14. __ mating: nonrandom mating based on phe-notypic similarity

16. Principle that states that gene frequencies in a population will not change over time if specific conditions are met by that population

17. Term meaning random mating