Flavia Nobay and Ryan P. Bodkin

BARTHOLIN CYST

The Bartholin glands (vestibular glands) sit at the 4 and 8 o’clock positions deep to the labia minora. Their function is to produce moisture for the posterior vestibule of the vagina (1,2). The Bartholin duct is a 2.5-cm structure that connects the glands to the vaginal orifice and is the conduit for these secretions, exiting onto the vestibule at either side of the vaginal orifice inferior to the hymen. The gland begins producing mucus at puberty and starts involution by 30 years of age, therefore cysts and abscesses of this region typically occur in women of childbearing years, most commonly between 20 and 29 years of age. Mucus retention, trauma, infection, inflammation, or physical blockages of the Bartholin ducts are etiologies for cyst and abscess formation and account for 2% of all gynecologic visits per year (1–3).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Most Bartholin cysts are asymptomatic and incidentally noted. Patients who present with a Bartholin cyst will complain of unilateral swelling, pressure and discomfort with walking, intercourse, or exercise over the course of days. Typically, a Bartholin cyst or abscess will be seen or felt unilaterally at the posterior vaginal introitus pointing medially (eFig. 133.1). Bartholin cysts are described as feeling soft or fluctuant and are usually well contained. Symptoms are based on the cyst’s size with smaller ones being asymptomatic (1 to 3 cm) and larger ones causing discomfort (4 to 8 cm) (4). A cyst does not need to pre-exist for an abscess to occur. Patient with severe pain or a rapidly expanding mass with intense pressure should raise concern for a Bartholin abscess (5,6). An abscess will have varying degrees of warmth, surrounding edema, and erythema extending into the superior portions of the labia. In some cases, cellulitis extends from the abscess causing more diffuse pelvic pain and low-grade fevers. Systemic illness is infrequently seen unless significant underlying medical illnesses coexist (6).

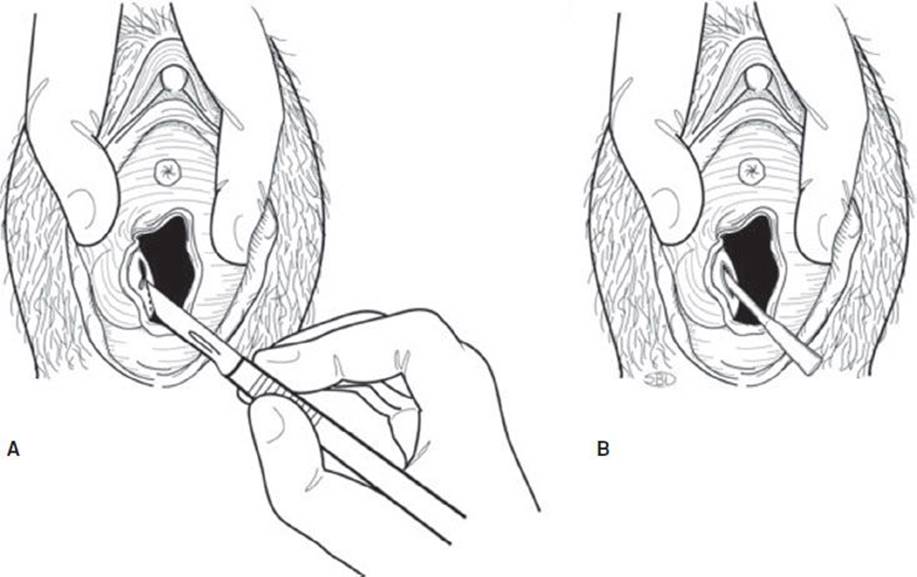

FIGURE 133.1 Treatment options of a Bartholin gland abscess. A: Incision and drainage: Make a 0.5 cm vertical incision over the vaginal mucosal side of the labia minora. B: Word catheter insertion: Insert the Word catheter as shown, inflate the balloon with approximately 3 mL saline. (From Simon RR, Ross C, Bowman SH, et al. Cook County Manual of Emergency Procedures. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011.)

eFIGURE 133.1 Abscess of Bartholin gland. © 1992, National Medical Slide Bureau, CMSP.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

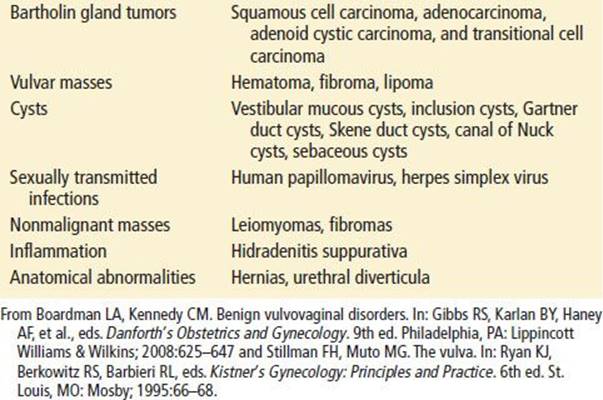

The differential diagnosis of a tender mass in the vaginal introitus is extensive (Table 133.1). Along with Bartholin cyst/abscess, providers must consider genital warts, herpes, syphilis, hematoma, hidradenoma, lipoma, as well as other varying anatomical cysts (5,6). Women over 40 years old have additional concerns for gynecologic malignancy. Although these diagnoses are rare (incidence of 4% of all gynecologic malignancies), a unilateral vulvar mass is a common clinical presentation for women with vulvar and Bartholin malignancy (7,8). Evidence such as age, time of onset, and systemic symptoms may help differentiate Bartholin and vulvar tumors from nonmalignant masses. Malignancies are described as irregular shaped, firm, fixed, and persistently indurated. Outpatient biopsy of the mass should be considered for any patient over the age of 40 presenting with a first time Bartholin or vulvar mass (8,9).

TABLE 133.1

Differential of Bartholin Cysts or Abscesses

ED EVALUATION

Patients with Bartholin duct cysts and abscesses require a careful history and physical examination. A complete history will include time of onset and duration of illness, systemic symptoms, a sexual history, and a gynecologic history including documentation of previous vulvar abnormalities. The physical examination should include visual and digital inspections of the external genitalia. If a vaginal discharge is present, a pelvic examination with appropriate cultures for sexually transmitted infections should be obtained.

Routine imaging and blood tests are not required for a Bartholin cyst. Cultures are helpful in understanding the changing microbiologic landscape of Bartholin abscesses. Bartholin cysts are generally considered sterile and abscesses are considered to be polymicrobial (10,11). The previous association of Bartholin abscesses with sexually transmitted infections has decreased from approximately one-third of isolates to less than a fifth of isolates (8% to 16%) with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis as the primary causative agents (12). Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are increasingly isolated from Bartholin abscesses (13–15). Pregnancy testing should be obtained on all patients of childbearing age.

KEY TESTING

• Routine testing and imaging are not helpful in most cases

ED MANAGEMENT

An asymptomatic, small Bartholin cyst should be conservatively managed without antibiotics. Similarly, small cysts that are minimally uncomfortable may be referred to an outpatient gynecologist for treatment. Abscesses that have already ruptured require only analgesia and local care with Sitz baths and warm compresses (4).

Cysts that are large enough to cause significant discomfort and Bartholin abscesses should be incised and drained in the ED. Most incision and drainage (I+D) procedures can be performed under local anesthesia with the aid of oral or intravenous pain medications. If a fistula tract is created, this procedure can lower the currently cited rate of recurrence of a Bartholin cyst or abscess of up to 17% (16). Inserting a Word catheter or Vaseline gauze for 4 to 6 weeks at the time of I+D allows for epithelization of the cyst or abscess cavity creating the desired tract. The Word catheter is a latex catheter with a balloon tip, which is filled with 3 mL of saline after insertion (eFig. 133.2).

eFIGURE 133.2 Word catheter before and after instillation of 3 cc sterile water. (From Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM, et al. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.)

Local anesthesia, and incision of the abscess or cyst should be on the mucosal surface of the labia minora (eFig. 133.3). The small vertical incision/puncture made with a no.11 scalpel blade should lie parallel but external to the hymenal ring at the 5 or 7 o’clock position. Incisions of the skin surface of the labia minora can result in increased complications. The incision (0.5 to 1 cm) should be large enough to allow for pus to be expelled and the Word catheter or gauze to be inserted but not fall out (Fig. 133.1). Tucking the catheter into the vagina after insertion increases patient comfort (17). In an effort to decrease recurrence rates and comfort for the patient, new therapies have been suggested for treatment in the ED, however no large studies have been performed to validate efficacy (18).

eFIGURE 133.3 The Bartholin gland abscess should be approached from the mucosal surface for local anesthesia, aspiration, or incision and drainage. (From Kovac SR. Advances in Reconstructive Vaginal Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012.)

Bartholin cysts or localized abscesses that are properly drained do not require antibiotics. If a patient is at high risk for a sexually transmitted infection, CDC guidelines for antibiotics treatment should be started after culture of the abscess (http://www.cdc.gov/sTD/treatment/2010) (19). Women who are at risk of complicated infections (immunocompromised, presence of cellulitis, or systemic signs of infection) should be treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic that includes MRSA coverage for 1 week (2,20).

DISPOSITION

All patient should be referred to a gynecologist for close follow up. Patients with recurrent abscesses, cysts, age greater than 40, or patients with concerning signs of symptoms for malignancy will need more urgent referral to an outpatient gynecologist. Sitz baths, pelvic care, warm compresses, and oral pain medication can increase patient comfort. Outpatient antibiotics are dependent on the clinical scenario. Patients should refrain from vigorous exercise or vaginal intercourse while the catheter is in place to prevent expulsion. If the Word catheter or packing falls out prematurely, it can be reinserted in the ED or referred to the gynecologist.

Common Pitfalls

• Moderate sized Bartholin cysts only require I+D if symptomatic, Bartholin abscesses should be drained regardless of size.

• Bartholin cysts do not require antibiotics, only selected populations with Bartholin abscesses require antibiotics.

• The incision for the I+D should be made on the mucosal surface as opposed to the skin side of the vaginal introitus.

• Confirm the patient’s allergies before placing the latex-based Word catheter.

REFERENCES

1. Rock JA, Jones HW. Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:71.

2. Omole F, Simmons BJ, Hacker Y. Management of Bartholin’s duct cyst and gland abscess. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):135–140.

3. Pundir J, Auld BJ. A review of the management of diseases of the Bartholin’s gland. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008:28(2):161–165.

4. Hill DA, Lense JJ. Office management of Bartholin gland cysts and abscesses. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(7):1611–1616.

5. Boardman LA, Kennedy CM. Benign vulvovaginal disorders. In: Gibbs RS, Karlan BY, Haney AF, et al., eds. Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:625–647.

6. Stillman FH, Muto MG. The vulva. In: Ryan KJ, Berkowitz RS, Barbieri RL, eds. Kistner’s Gynecology: Principles and Practice. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995:66–68.

7. Bodelon C, Madeleine MM, Voigt LF, et al. Is the incidence of invasive vulvar cancer increasing in the United States? Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(9):1779–1882.

8. Canavan TP, Cohen D. Vulvar cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(7):1269–1275.

9. Visco G, Del Priore G. Postmenopausal Bartholin gland enlargement: A hospital-based cancer risk assessment. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:286–290.

10. Sherer DM, Dalloul M, Salameh G, et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia and chorioamnionitis after recurrent marsupialization of a Bartholin abscess. Obstet Gynecol.2009;114:471–472.

11. Kessous R, Aricha-Tamir B, Sheizaf B, et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Bartholin gland abscesses. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):794–799.

12. Bleker OP, Smalbraak DJC, Schutte MF. Bartholin’s abscess: The role of Chlamydia trachomatis. Genitourinary Med. 1990;66:24–25.

13. Tanaka K, Mikamo H, Ninomiya M, et al. Microbiology of Bartholin’s gland abscess in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4258–4261.

14. Brook I. Aerobic and anaerobic microbiology of Bartholin’s abscess. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:32–34.

15. Thurman AR, Satterfield RM, Soper DE. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a common cause of vulvar abscesses. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:538–544.

16. Wechter ME, Wu JM, Marzano D, et al. Management of Bartholin duct cysts and abscesses: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64(6):395–404.

17. Kilpatrick CC. Bartholin gland abscess or cyst incision and drainage. In: Reichman EF, ed. Emergency Medicine Procedures. 2nd ed. China: McGraw-Hill; 2013:930–935.

18. Kushnir VA, Mosquera C. Novel technique for management of Bartholin gland cysts and abscesses. J Emerg Med. 2009;36(4):338–390.

19. Workowski KA1, Berman S; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1–110.

20. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections. Clin Infect dis. 2005;41:1373–1406.